Could stevia be a sweet new crop for U.S. producers?

- Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni is a plant native to Paraguay that produces calorie-free, sweet-tasting compounds called steviol glycosides.

- Issues with bitter flavor and cold intolerance have kept U.S. producers from growing the perennial, but researchers have been working hard to discover breeding and agronomic means to overcome both problems.

- Here, researchers discuss studies on stevia’s flavor and agronomic qualities, findings about consumer preferences, and the challenges for producing this new, potentially lucrative crop in the United States.

This really feels like Apple computers in 1984,” Todd Wehner says excitedly. “But ‘Keep your shirt on,’ I tell my growers. Start slow, try it out, see how it works. We’re right on the cusp of something big here.”

Wehner, a longtime cucumber and watermelon breeder at North Carolina State University and an ASA and CSSA member, cannot say enough about Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni (stevia). The bushy, perennial plant in the sunflower family produces noncaloric, sweet-tasting compounds in its leaves that are up to 300 times sweeter than sugar without the blood sugar spikes. If you have ever dabbled with health foods or tried to find a less sugary means of enjoying your favorite treats, you’ve likely run into erythritol, xylitol, aspartame, and an abundance of other artificial sweeteners.

But unlike the artificial options in the baking aisle, stevia has a long history outside the laboratory. In its native Paraguay, the plant is known as “sweet herb” to the indigenous Guaraní people who have used it to make herbal teas for thousands of years. A big draw for American consumers is stevia’s natural sweetness—the sweet-tasting compounds, called steviol glycosides (SGs), are produced in the plant’s leaves and then extracted and concentrated to at least 95% purity for use in foods and beverages.

There are a few things keeping the food and beverage industry—and growers—from incorporating the plant in their rotations, despite its massive market potential as a natural alternative to sugar. First off, the primary SG that stevia synthesizes in abundance has a bitter aftertaste. Plus, stevia varieties lack cold tolerance, and farmers face the agronomic challenges of growing a new crop and the pressure of finding a buyer for their harvests.

Here, we’ll breakdown the triumphs and challenges facing stevia so far. We’ll talk to scientists breeding for taste and testing consumer perceptions, chat with researchers finding ways to overcome agronomic challenges, and hear from an industry member who hopes to bring the plant’s production to the United States in a big way.

Begone, Bitter Taste

“It’s really exciting working with a crop that’s a blank slate,” Ryan Warner says. “It’s not like maize or wheat where we’ve been making gains for particular traits for thousands of years—stevia is something novel, with potential commercial applications, and it’s something consumers are looking for, too.”

Warner, an associate professor in the Department of Horticulture at Michigan State University, had never heard of stevia before a company called PureCircle approached him more than 10 years ago, asking for his help developing new varieties. Since then, Warner has coordinated multiple projects with funding from PureCircle and a USDA Specialty Crop grant.

“Stevia has over 30 different sweet-tasting compounds, but the predominant one has a bitter aftertaste. There are others, though, with superior taste profiles,” Warner says.

That bitter-tasting compound is an SG called Rebaudioside (Reb) A. Until now, it’s been the primary stevia extract produced for the food and beverage industry, and it does, indeed, taste a bit metallic.

Now for a smidgeon of organic chemistry: Reb A is an SG with a diterpene ring backbone called steviol. Steviol has two carbons where glucose molecules—the part that hit our sweet receptors—attach. Reb A has three glucose molecules on the first carbon attachment and just one on the second. But Reb D has two glucoses on the second carbon, and Reb M has three. Those extra glucoses might just do something to mask the bitter taste of the steviol backbone.

In a study published in Industrial Crops & Products, Warner and his coauthor, Veronica Vallejo, tested several different varieties of stevia from the Michigan State breeding program to create a reference transcriptome, helping them see if SG production linked to specific coding regions in stevia’s DNA (https://bit.ly/3te4CoF). The duo found two locations in the reference transcriptome that explain 10–14% of the variation in Reb D concentration in their tested varieties. They also found several locations linked to Reb A production, too.

“We had an inkling, but this really helps establish it: the production of glycosides is largely genetically determined,” Warner says. “There’s environmental influence that might change the amount of glycosides found in the dry [leaf] matter, but the proportion is largely stable across production environments.”

This finding is a great step forward for production in the U.S., where growing environments vary wildly. For example, if a breeding program releases a variety that is bred to produce a larger proportion of Reb D compared with Reb A, a grower won’t try it in a new environment and find, suddenly, that their stevia plants produced more Reb A compared with D.

“It’s a big deal for flavor,” Warner says. “We can move some of these superior genetics into new varieties with high hopes they’ll be stable across production environments.”

Consumers Taste-Test Stevia

Warner’s research shows promise for changing Reb proportions in stevia varieties, but will consumers like what they taste?

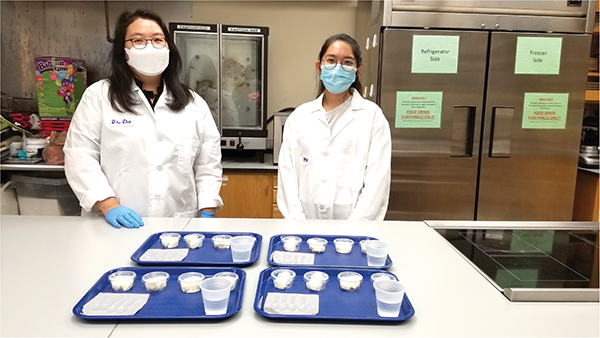

This is the question Sungeun Cho, an assistant professor at Auburn State University (previously an assistant professor at Michigan State), is testing out.

In a study published in Foods last year, Cho and her team set up a panel where untrained consumers tasted solutions of sucrose, Reb A, Reb D, and Reb M at equivalent levels of sweetness (https://bit.ly/3diDZcx). Participants tasted the solutions and then checked aftertaste attributes from a list, including words like “artificial,” “bitter,” “honey,” “licorice,” “metallic,” “vanilla,” and “pleasant.”

Participants were much more likely to describe the aftertaste of Reb D and M as like “honey” and “vanilla” compared with Reb A. Both descriptors denote a more natural taste compared with Reb A’s “artificial,” “chemical,” and “metallic” tastes.

“We found that Reb A has significant bitterness,” Cho says. “But Reb D and Reb M clustered much closer to sucrose in our flavor tests. There’s still something that makes them different from sucrose, too; some kind of aftertaste, but we don’t have the right word for it. My grad student says it has a kind of ‘airy’ taste.”

But these were tests in solution—Cho has big plans to try out different combinations of SGs with cold desserts like ice cream, or baked goods like muffins, to see how the flavors play out in a food matrix.

The consumer panels are a first step to guide breeders’ directions when selecting for stevia varieties with more favorable proportions of SGs. Eventually, producers hope to circumvent one of the major issues keeping the food and beverage industry from using these better-tasting Reb compounds: cost.

Since the dominant SG found in dry leaf matter, Reb A, is so bitter, food and beverage producers typically use other isolated Reb extracts. This means discarding all of the other SGs found in dry leaf matter to get just one specific, concentrated Reb compound. It’s kind of like picking out all the chocolate from the trail mix: a super expensive way to get your sweet fix.

“Reb D is very expensive, coming in at $300 or more per kilogram,” Gabe Gusmini says. Gusmini is the chief executive officer and co-founder of The Plant Pathways Company (which Wehner also co-founded). The company aims to bring stevia production to the United States. “Beverage producers need a sweetener to be between $45 and $75 for it to be viable in mass production.”

If stevia breeders, like Warner and Wehner, can create varieties with more desirable proportions of SGs, then processors could extract all the sweet compounds from the leaf instead of just isolating one. This would drive the cost down.

“You can picture it: it could be that Reb A dominant stevia is great in donuts, Reb D is perfect in ice cream—there’s all kinds of ways we could use new varieties to meet consumer demand,” Wehner says. “We have the machines, the production methods, the varieties. People really want this.”

Agronomic Challenges

Speaking of production methods, stevia researchers are tackling agronomic challenges facing farmers trying out stevia as a cash crop. Here are the big three: cold tolerance, seed germination, and weeding.

Stevia is not fond of the cold, so one of the biggest challenges to producing it in the United States in a way that makes it cost effective is overwintering the crop.

“If you’re growing it [stevia] north of North Carolina, you’d need to do it as an annual. If you’re growing it south of North Carolina, you can leave it in the ground for three to five years,” Wehner says.

Would it be possible to grow a perennial stevia plant north of North Carolina?

Wehner’s team conducted a study recently published in Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment to see if there are any stevia varieties capable of handling cold snaps (https://doi.org/10.1002/agg2.20120).

The team used 14 half-sib plants (plants with one shared parent—stevia is self-incompatible), propagated them with cuttings, creating clones that they then put in controlled growth chambers at 2, 0, –2, or –4°C. The team left batches of plants from each variety in the chambers for 2 to 10 days and assessed plant damage on a scale of 0 to 9, with 0 being no damage two weeks after chilling, and 9 being death.

Though all the plants died after just four days of exposure at –4°C, there are varieties capable of weathering –2°C temperatures and higher. Two cultigens were consistently cold tolerant, showing that there’s hope for selecting cold-tolerant varieties for production farther north.

Perfect—Wehner’s team shows there is genetic potential to breed cold-tolerant varieties. But what does production look like?

Right now, growers are reliant on transplanting greenhouse-propagated clones into the field using equipment like lettuce transplanters, which is expensive and time consuming. The seed germination rate of stevia is notoriously low, preventing cost-effective seedling growth in greenhouses, and definitely too expensive to direct-seed in the field. Germination rate is a big “to do” in variety development. “If you can direct-seed, it becomes an annual crop you can plant anywhere and get cash,” Gusmini says. “But the seeding problem is not a one-step thing. I want to say we’ll get seeded stevia in five years, but realistically, it’ll be more like eight. We’ll get these plants to the point where enough of the seed germinates that we can spread it into the field, and that will cut back on costs.”

Once the plant is in the ground, yields are low the first year as it establishes a healthy root system though you can still harvest. It’s really in Years 2–5 that growers will see bigger yields. Researchers can harvest leaves using leaf-stem separators typically used for soybean operations.

“You have to crank it up a bit, cause you’re trying to yank the leaves off the stems,” Wehner says. “But it works pretty well!”

There’s some debate about whether growers should harvest multiple times over the growing season or wait until the end. Multiple harvests take more time and labor for roughly the same yield, but guarantee income if something happens to the crop.

“Stevia is prone to lodging under high winds—we’re talking hurricanes, here—but you can pick up the stems and cut the plant down to the crown, and it will grow back the next year,” Gusmini says. “That’s the great thing about it.”

Wehner recommends growers plant stevia in fields with tree lines to break up the wind and perhaps seed rye along the spray row. The duo sees stevia as a great option for farmers transitioning or diversifying their tobacco operations since they already have most of the equipment it takes to grow stevia. Greenhouses with float systems work great for growing up stevia transplants, and stevia loves well-draining soil and lots of water.

“Stevia has scalability, and because it’s 300 times as sweet as sugar, you can cut back on acreage and heavy equipment compared with sugarcane to produce the same amount of sweetness,” Gusmini says. “But it was only recently labeled a herb in the United States, so moving forward, it will be easier to register herbicides and fungicides for stevia.”

Weeding is the biggest cost for growers right now. Herbicide production will help, plus the team has found stevia doesn’t play well with peanut, which shares several diseases. It works well with tobacco (especially considering the shared equipment), and Gusmini even thinks farmers used to working with perennials like oranges, or potato growers who are used to implementing long rotations, would be great candidates to try it out.

Scaling Up Production

Scientists are putting all the puzzle pieces in place to produce stevia with better flavor, but they need a buyer to finish the picture.

“We finally have someone interested in buying and processing the harvested leaves,” Gusmini says.

Globally, the artificial sweetener market value was $7.2 billion in 2020, but market research forecasts it will grow to $9.7 billion by 2025. But that only includes high-intensity sweeteners like aspartame and saccharin. On the other hand, industrial sugar—including sugarcane, sugarbeet, and other sugar sources—commanded a global market value of $65.35 billion in 2018, with expected growth to $65.35 billion by 2026.

With whole-leaf stevia extracts, labels could read “natural,” which is a big draw for consumers, and only one ingredient—stevia—would be in the list. This is another plus for label-savvy grocery shoppers.

“We want to see stevia in as many products as possible, labeled as a natural sweetener,” Cho says. “As people learn more and more about it, they’re open to try it; they have better perceptions.”

“Get the sugar out of the way!” Wehner exclaims. “There are so many better options, and there are not many things in nutrition we can agree on, but pretty much everyone agrees you shouldn’t have sugar.”

“Get the sugar out of the way! There are so many better options, and there are not many things in nutrition we can agree on, but pretty much everyone agrees you shouldn't have sugar.”

And there’s one final piece: as more and more farmers try out stevia on a bigger scale, we’ll discover new challenges to overcome. That’s where extension comes in.

“This isn’t just about seed companies and growers,” Gusmini says. “The more we can involve the extension service, the better. Once we have this going, we’ll need departments in universities to support extension agents working with stevia to make it a priority so we can help growers.”

And so it comes full circle: consumer preferences drive variety development, new varieties may lead to better agronomic qualities for producers in the field, and market research leads to processors and industry investing in stevia production. It’s an exciting area—one that we’ll have to keep an eye on. Like Apple in the 1980s, let’s see if stevia makes it from a garage startup to ubiquitous industry leader.

Dig Deeper

Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment article, “Cold Tolerance of Diverse Stevia Cultigens under Controlled Environment Conditions” at https://doi.org/10.1002/agg2.20120.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.