Rewriting the story on raspberries

Below some of the most productive and intensively farmed agricultural land in Canada sits the sprawling Abbotsford-Sumas aquifer. Levels of nitrates in the water remain high despite a growing body of research on the causes and consequences of these nitrates, as well as efforts to reduce them by modifying farming practices.

An interdisciplinary team of researchers spent several years experimenting with different management strategies for red raspberries, one of the region’s top crops. They compared various approaches to fertilization, irrigation, and cover crops, examining their effects on nitrate leaching and crop performance.

Their findings add to a growing body of evidence suggesting that, by combining a variety of these practices, farmers could minimize harmful leaching without jeopardizing their bottom line.

Midsummer is peak harvest time at many berry farms across the Pacific Northwest, including the hundreds of growers who tend the juicy, flavorful, and nutrient-packed red raspberry (Rubus idaeus). As these farmers (and almost anyone who has ever purchased their fresh wares) well know, these plush, fuzzy aggregates are also among the most delicate of fruit. Farmers take great care during the harvest to minimize handling and get them swiftly to the market, freezer, or processor. And woe to the untrained shopper who purchases a carton without first scrutinizing them for mold.

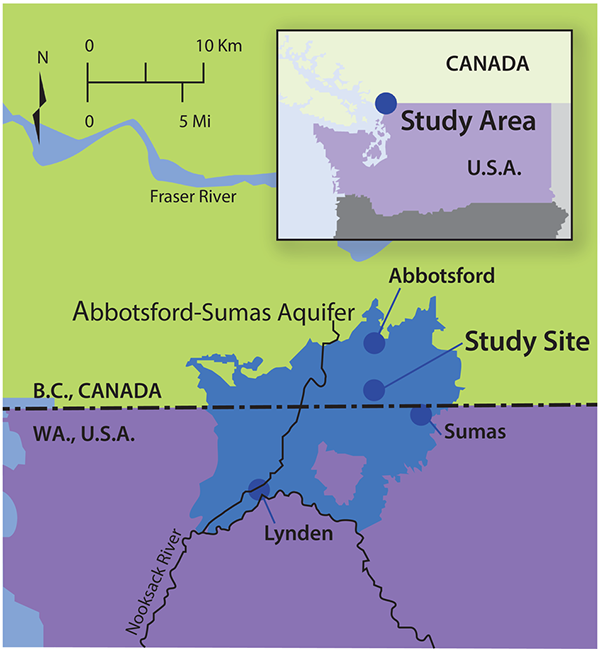

As it turns out, the environment where most of Canada’s and much of the United States’ crop is grown is also quite delicate, in part due to an unconfined aquifer above which the ruby gems are planted. The 200 km2 Abbotsford-Sumas Aquifer straddles the border between British Columbia, Canada, and Washington’s Whatcom County, in an area roughly between Vancouver and Seattle. Plentiful water from that aquifer, along with the temperate maritime climate, loamy, well-drained soil, and proximity to manure-generating farms (poultry, north of the border, dairies on the U.S. side) have offered favorable conditions to berry farmers for generations.

By the 1980s, however, scientists had begun to grasp the true price tag of decades of “free” water and fertilizer. The cost was tallied not in dollars, but in the aquifer’s nitrate levels—levels that, in many instances, surpassed both countries’ safe drinking threshold of 10 mg L-1. For an aquifer that provides drinking water to more than 150,000 people, it was unsettling news.

As evidence implicating the use of manure mounted, scientists published research that led to new guidance on how farmers could reduce the amount of nitrate leaching from their soils without impacting their yields, which surpassed 34,000 metric tons across the Pacific Northwest in 2020. These best management practices, or BMPs, included forgoing raw manure in lieu of fertilizer or composted manure, and better aligning the amount applied to the amount needed. Restraint was also encouraged for irrigation, as was planting cover crops between the rows of berry bushes.

Some farmers implemented some of these measures. Some did not. Unfortunately, there’s no clear picture of what occurred, according to Tom Forge, a research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s (AAFC) Summerland Research and Development Centre in British Columbia. “There was nobody really keeping track,” he says.

Whatever did—or didn’t—happen was not enough to move the needle on nitrates: Ongoing monitoring shows levels remain elevated.

That’s the main motivation behind a four-year study initiated by AAFC soil scientists Bernie Zebarth and Denise Neilsen (both now retired) and Forge, a plant pathologist specializing in nematodes and soil-borne diseases. Funded by AAFC, the team managed plots of raspberries near Abbotsford—Canada’s “raspberry capital”—using a number of different combinations of practices. In a pair of papers, the first published in 2020 in Vadose Zone Journal (https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20054), the second appearing late last year in the Soil Science Society of America Journal (https://doi.org/10.1002/saj2.20190), the team quantified the effects of nitrogen (N), irrigation, and alley management strategies first on leaching, then on berry yield and health, including the role root-nibbling nematodes play in this drupelet drama.

Parsing the numerous variables was a tough challenge. But before we dive in, try this quick pre-test. After all was said and done, which nitrate-reducing strategy did the team determine was most effective?

1. Irrigate more strategically.

2. Plant annual or (even better) perennial cover crops.

3. Poo-poo raw manure and opt instead for fertilizer or compost.

In the past, farmers may have selected one correct answer to implement, says Shawn Kuchta, a longtime research technician at Summerland and first author on the two papers, which grew out of his master’s thesis. But the best answer, according to this research, is:

All of the above.

“Perhaps producers chose one approach to take and, really, it needed to be multiple things at once,” says Kuchta, who came to Summerland in 1999 for a three-month stint and never left. “That’s what jumped out at me as perhaps part of the answer as to why we’re still chanting the same story now.”

Indeed, if this story was a novel, it would be more slog than thriller: Change can take time. Luckily, the interdisciplinary team, which also included University of British Columbia hydrogeologist Craig Nichol, together boast more than eight decades of experience studying nitrate levels. Spanning two academic generations, the researchers are working to rewrite the story of nitrogen in the Abbotsford-Sumas aquifer in the hopes of steering it toward a happier ending. Below, we condense that story into three key chapters on the roles of nitrogen, irrigation, and cover crops.

The Law of Nitrogen Demand and Supply

The Abbotsford-Sumas aquifer area boasts a nitrogen surplus. “There’s a lot of intensive poultry cheek by jowl with the berry production,” explained Forge. “We have a lot of situations where there will be 60,000 laying hens in this Quonset hut over here, and then you’ve got raspberry fields all around it.”

Historically, that easy access may have prompted farmers to apply manure more liberally than needed, resulting in a classic case of too much of a good thing. The research team’s work helps reframe the thinking on fertilization in terms of plant demand, rather than nitrogen supply.

To understand the impact of raw manure and different levels of fertilizer on the environment, the researchers had to dig—1.5 m, to be exact. That was the depth of the 32 holes they excavated—each large enough to accommodate a small tea party, as Kuchta described it—in which they installed instruments to measure nitrate levels in water captured beneath the plants and the alleys between them. The researchers took care to reconstruct the original soil profile when refilling the holes, a painstaking process.

“Even though it was all backhoe-and-shovel grunt work, it was actually technically demanding to get that initial installation,” Forge recalled. Once the samplers were established, the team collected data through heat, downpours, and mud-slicked alleys every two weeks for four years.

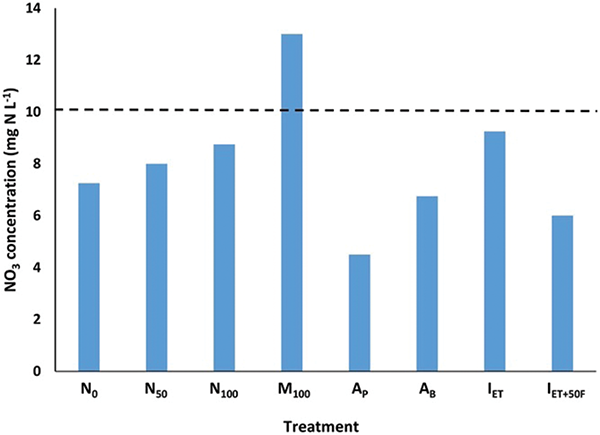

The management scenarios studied by the team included the conventional approach practiced by most raspberry farmers in the region: Broadcast 100 kg N ha−1 in two applications, irrigate every two days, and clean-till the alleys. The other scenarios tested included applying enough manure to approximate that same amount of nitrogen; broadcasting just 50 kg of fertilizer; applying that lower amount of fertilizer through daily irrigation (i.e., fertigation); irrigating by plant demand; and planting cover crops in the alleys.

Finally, after thousands of soil, water, and plant samples had been stored, transported, prepped, and analyzed, the team published its findings on nitrate leaching. When they compared nitrogen treatments, they found that rows treated with raw manure resulted in the most leaching—more than twice as much as rows that received the conventional 100 kg of fertilizer. Given previous research, that did not come as a surprise. Less expected, however, was the difference in leaching measured among the plots treated with varying amounts of fertilizer—or rather, the lack of difference. Whether those plants received the conventional application, half that amount, or none at all, the degree of leaching was about the same—and it was high.

The findings, the scientists say, point to the fact that farmers deal not only with the nitrogen they apply, but also with nitrogen that’s already there. The likely sources of this “unmanaged” N: Atmospheric deposition from nearby poultry farms; residual nitrogen left over from previous fertilizations; and irrigation water drawn from an aquifer into which decades of nitrates have leached.

Kuchta did the math, and what he found surprised him. When he multiplied the 20 mg N L–1 that had been measured in the irrigation water by the amount of water used in the conventionally irrigated treatments, he calculated that the researchers were inadvertently adding to the plants considerable amounts of nitrogen that they had not factored in.

“It turns out that our ‘zero N treatment’ actually had 60 kg of N applied per hectare,” Kuchta says. This meant that their 50-kg treatment was 110 kg, and their 100-kg treatment was 160 kg, when accounting for the N in irrigation water.

“We all knew—that’s the reason we’re doing the work—that the groundwater had nitrate in it,” Forge says. “But I don’t think anybody fully appreciated that—had actually done the calculations.”

All of which begs the question, of course: With so much unmanaged nitrogen available to the crops, do farmers really need to add anything to boost yields?

Arguably, no. The researchers found that the yield and health across the range (0 to 100 kg ha−1) of fertilizer-treated crops in their study, as well as for the manure-treated crops, was generally comparable.

But cutting back on fertilizer can be a hard sell for farmers, says Chris Benedict, an agricultural agent for Washington State University (WSU) Extension in raspberry-rich Whatcom County. Benedict, a member of ASA, CSSA, and SSSA who is familiar with the VZJ and SSSAJ articles and conducts his own raspberry research on the U.S. side of the aquifer, has spent more than a decade communicating with growers about the benefits of nitrogen-reducing practices. It’s a slow process, he says, because farmers see change as risk.

“A lot of what people do now is what they learn growing up, whether it was their parents or some other farm they worked on,” Benedict says. “It’s kind of hard to break that cycle.”

Though modest, change is heading in the right direction, Forge says. The official growers’ guide for Canadian raspberry farmers, for example, has evolved to include information on the benefits of composted over raw manure. Although hard data is lacking, the consensus is that use of raw manure has been in decline.

“There is some slow progress being made,” notes Forge, who worked on farms in eastern Kansas growing up. “Whether it’s enough to make a dent in the amount that’s being leaked to the aquifer over the next 10 years … it’s hard to say at this point.”

What is clear, Kuchta emphasized, is that to have a significant impact, farmers need to consider more than just reducing nitrogen inputs, which in and of itself is no “magic bullet.” With additional bullets, in the form of other BMPs, farmers could get closer to the target of sustainability.

Which brings us to the next chapter of this story.

Testing the Irrigation Waters

Nitrogen hasn’t been the only perceived free resource for raspberry farmers planting over the Abbotsford-Sumas aquifer. “Historically, the water was seen as almost free,” Forge says, “because the aquifer was viewed as limitless.” Growers there favor conventional drip irrigation, which runs like clockwork, several hours every two days or so, regardless of conditions. When you’re unsure exactly how much water you need, it’s cheap insurance.

In their study, the team compared that practice to evapotranspiration (ET)-scheduled irrigation, which is based on plant demand, rather than the water’s ample supply. They learned that cheap insurance isn’t such a bargain, after all.

Using a device called an atmometer, the team measured water lost by evaporation from the soil surface and by transpiration by the crop. Resembling a rain gauge, the tool is topped with a cover that simulates the surface of a crop. Kuchta explained how it works.

“Over the course of a growing day, we record a total amount of evapotranspiration lost, as simulated by that surface that is losing water out of that water reservoir,” Kuchta says. That data is added up at day’s end, then used to calculate the next day’s irrigation needs.

“That little calculation,” Kuchta continued, “happens in a split second at midnight and tells us exactly the amount of time, down to the minute, that we need to turn the water on in that system the next growing day to replace what was lost the day before. So, it’s about as efficient as you can get right now.”

The approach has been implemented successfully on other fruit crops in the area, he says. This study showed it also works well on raspberries when comparing crop yields. It could save growers money on electricity, potentially thwart root rot, and reduce both the amount of water used and the amount of unmanaged nitrogen that water contains by more than half.

“When those drippers are delivering several liters per hour, the amount of water adds up fast,” Kuchta says.

But, although you can lead farmers to better water management practices, they may not embrace them.

“This is probably the biggest issue for multiple generations for this region,” says Benedict who, in addition to his extension duties, serves as WSU’s lead for the Washington Soil Health Initiative, a partnership among the university, the Washington State Department of Agriculture, and the State Conservation Commission. ET irrigation is still rare in Whatcom County, he says, particularly among large-scale growers.

“That means they might have a 100-acre field with seven zones of irrigation, and they can only turn one on at a time,” Benedict explains. “So, they’re just constantly cycling through that. They’re just trying to keep things wet. ET would be great, but I think it’s just complicated to people.”

A Cover Story

Having covered nitrogen and irrigation, we now turn the page to cover crops. Although last on this list, it is by no means the least important variable. In fact, of all the management scenarios tested in the alleys during this study, use of a perennial forage grass was by far the most effective at reducing nitrate leaching, resulting in nine times less leaching than was measured on an annual cover crop of barley. An important bonus: Neither cover crop reduced raspberry yield.

Making the finding especially impactful is the fact that alleys make up 60% of raspberry fields, to accommodate the harvesters that carefully coax the ripe fruit from their perches and other machinery.

While most producers still practice clean tilling, a growing number are planting an annual cover crop—up to 45% of Whatcom County’s raspberry acreage, Benedict estimates. Perennial cover crops have been much slower to catch on. Although common in the region’s blueberry fields, raspberry farmers have voiced concerns that the grasses pilfer resources meant for the bushes and encourage nematodes, even though research doesn’t support those suspicions, Benedict says.

Alley management is also conspicuous, which could make farmers especially wary.

“Businesses in general are very complicated,” Benedict observed, “but I think farming is somewhat unique in that most of it happens outside. And a lot of how your neighbors perceive you can drive your decisions, especially in a small, rural community.”

While Benedict negotiates the border between science and practice, Kuchta and Forge continue to build a case for better management practices with their research. For example, a graduate student from the team used nitrogen-15 to trace one year’s application of fertilizer: Exactly how much did the plant absorb, and how much leached into the groundwater? They are working to publish the results in the near future.

Another fertile area for research is the role root-lesion nematodes (Pratylenchus penetrans) play in the nitrogen cycle of raspberries, which the SSSAJ paper examined for the first time. Those findings suggest a relationship between fertilizer applications and nematode populations: Damage caused by the pests could keep the plants from absorbing the nitrogen intended for them, potentially diminishing yield. That’s the type of insight that interdisciplinary teams like this make possible. Further investigations could shed light on how more effective nitrogen management could also improve pest management.

Every new study can help advance the sustainability story, says Forge, who takes a long and optimistic view. “These things always take time,” he says, “and they take a lot of research. No one experiment is ever a slam dunk.”

Perhaps what this narrative needs most, suggests Kuchta, is a good hero—a farmer willing to test and champion a new practice. “You just never really know when someone’s going to grab onto one of the concepts and say, ‘You know what? This is not complicated to do,’” he says.

Even better might be a trio of heroes—one each to champion better practices for fertilization, for irrigation and for cover crops, working as one squad. After all, says Kuchta, “It’s the combination of multiple BMPs that we believe has the greatest potential to have a significant impact.”

Dig deeper

Read the orginal articles: “Nitrogen, Irrigation, and Alley Management Effects on Nitrate Leaching from Raspberry” in Vadose Zone Journal at https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20054 and “Nitrogen, Irrigation, and Alley Management Affects Raspberry Crop Response and Soil Nitrogen and Root-Lesion Nematode Dynamics” in the Soil Science Society of America Journal at https://doi.org/10.1002/saj2.20190.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.