Participatory on-farm research during graduate school: Challenges and opportunities

Including farmers, growers, and ranchers (hereinafter referred to as producers) as active participants in the development of knowledge, through extension and on-farm research programs, is an effective method of agricultural technology and innovation transfer. The emerging interest in understanding agricultural systems’ complexity has fostered collaborations between producers and land grant universities, particularly across graduate programs focused on applied research. While the concept of on-farm research1 is not new, the scale and impact of on-farm studies conducted by researchers in partnership with producers are expanding (Kyveryga, 2019). Can master’s and Ph.D. research projects be conducted at the farm scale and generate data-driven recommendations to improve producers’ management decisions? Based on our graduate school experiences working with on-farm trials in agronomy, crop science, soil science, and entomology areas, our opinion is that the answer to both of these questions is a resounding “yes.” Recognizing the opportunities and challenges in conducting on-farm studies as part of master’s or Ph.D. projects, we offer our reflections and recommendations to hopefully help and encourage other graduate students who may be considering initiating on-farm studies.

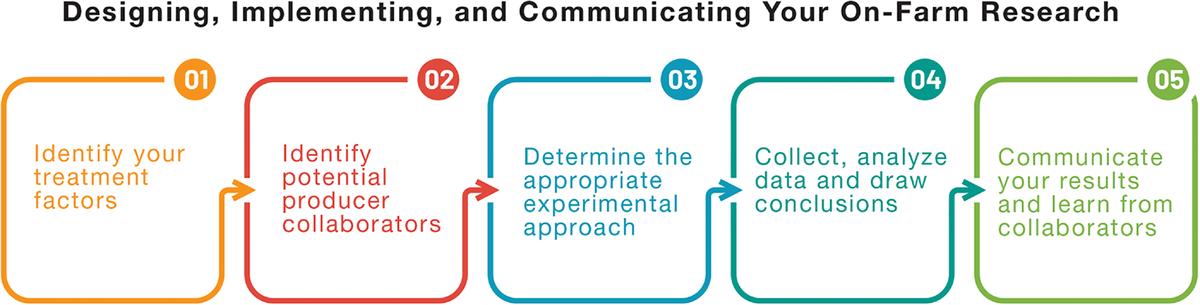

Identify Factors for Experimentation: Understand the Needs

Whether you are conducting your study on traditional small-plot replicated field experiments or adding an on-farm component, understanding the needs and defining the topic and objectives early in the process is critical. Your research goals should be specific, but keep in mind, that producers in their everyday decisions are fine-tuning and optimizing multiple management factors. Added to that, they may be more likely to implement practices through incremental changes rather than rapid or drastic changes to their operational structure.

Even though most on-farm studies are implemented to ensure consistency of the treatments, make sure to take into account the role of producers’ preferences in your region for management practices and implementation timelines, which could shape your project’s impact on producer’s decisions. Make sure to find a balance between your research goals and goals that are reasonably achievable from a producer’s standpoint (things that they can work on after the project is completed). Finding this balance is vital for increasing producers’ engagement.

Creativity and innovation are always welcome in designing an experiment that will eventually lead to producers’ improvements in management decisions and production systems’ sustainability, even if they come with a reasonable level of “risk.” Thus, when incorporating on-farm research into your project, challenge yourself and think “out of the box” to identify experimentation factors that can realistically lead to the producer’s improvement in management decisions.

Identify Producer Collaborators and Site Selection: Create Partnerships

Once you are clear on your general type or category of treatments, it is time to use your professional network to identify potential farmers and field sites. Identifying the right producer and right field site is crucial for your on-farm study success. A strategy that has helped us identify the producer is asking suggestions of potential collaborators from crop advisers, extension educators, county agents, professors, and other students involved in on-farm research within your region. When you ask for potential producer’ names, make sure to mention the objective of your study, the size of the area needed, the location of the area (in case you plan to have field days), the benefits that producers will get from participating in your research, as well as the best method to contact them (e.g., phone call, email, or text).

Identifying the right field site that will follow all of your research requirements is key for your on-farm study’s success. Developing a field selection criteria list is a great strategy to ensure that the farmer is aware of your study requirements. You should ask yourself: Do I need a specific crop rotation? Do I need an irrigated area? How large is the study area needed? How far from where I am located (logistics in transporting equipment, etc.) should the site be? Who will be responsible for planting, weed control, nutrient management, and harvest? Who will be applying the treatments? What are my responsibilities, and what are the producers’ responsibilities? Are there any limitations on what can or cannot be applied? Make sure to discuss those requirements in early conversations with the producer(s), so you can realize the fit, and then they can help you identify the best site on their farm for your study. Having clear communication of who does what in the study area from the beginning of your conversation will facilitate your communication throughout the season.

After identifying possible names and having your research requirement list finalized, it’s time to contact the producers. Make sure to do that in advance, before the season starts. Follow the best method to contact them, and try to get straight to the point, but make sure you explain all the important information and background of the plans (answering the “what” and “why”). In the phone call, text, or email, schedule a farm visit to meet the study area to discuss more of the details. After the producer agrees to participate in your study, you can use a research agreement or “contract.” This is an official agreement to secure that the producer is willing to be part of your project and is aware of the project’s scope, purpose, requirements, and research team responsibilities (farmer’s monetary compensation for joining the study, if applicable, can be discussed accordingly). Several funding agencies require such agreements to be included in grant proposals.

Use Suitable Experimental Approaches: Plan Your Data Collection Accordingly

After identifying the producer(s) and field site, it is time to make sure you have a suitable experimental design and data collection plan to answer all, or at least most, of your research question(s). The way you conduct on-farm experiments has some particularities that may not apply to traditional field experiments, especially in experimental design and sampling strategies. When it comes to on-farm studies, students often ask, “should I have detailed measurements with few sites or fewer determinations with more sites?” There is no right or wrong answer to this question, which depends on the novelty of what has been studied, your research questions, and funding availability. Our recommendation in the field of soil science suggests you should consider restricting the numbers and types of measurements made to key measurements in a few well-defined areas of the field. Also, consider a narrow range of treatments (compared with what you would consider as a treatment range in a small-scale study) to be repeated across all of your on-farm sites. In terms of management comparison, focus on large management changes (e.g., comparing a standard farmer practice versus improved practices). You are more likely to see differences if you focus on larger management changes rather than smaller changes. Last, be consistent with your sampling strategy, including sampling at the same time of year, the same location in a field for subsequent years, and use the same methodology for field and laboratory analysis.

You may also consider a “mother-and-baby” trial strategy to your project, which is when you combine trials located both on a research station and on a farm. The “mother” trial is replicated most likely in an experimental research station to test a wide range of treatments and research hypotheses. The “baby” trial comprises a number of satellite trials of large plots replicated on a farm and considers a subset of the treatments tested in the “mother” trial. Whether using a mother-and-baby trial or another design strategy, it is important to maintain a “control” plot with the original producer’s practices as a comparison from the research perspective.

How long on-farm studies should be replicated in time depends on the process under investigation and your research question(s). For example, some changes in soil properties are a long-term improvement process. That means monitoring soil changes due to management requires longer periods, preferably a minimum of three to five years. On the other hand, some insect pest problems are sporadic, so more field sites in a year instead of replications over time would be more appropriate. Also, the number of repeated measurements, either in space or time, will depend on how variable your measurements are. For example, measurements focused on soil biology are highly variable. Even if you see large differences over time, be careful on making conclusions about whether your treatment effect is statistically significant or not. Because of these measurements’ highly variable nature, it will be challenging to determine if those differences are real or just due to random error. You will need tests over multiple years to determine if a trend is consistent or not.

An important consideration here is to acknowledge in-field spatial variability when using large-scale field production. One way to address spatial variability is, as said previously, to take measurements in well-defined areas of the field (homogeneous measurement zones). Spatial classes for sampling (or measurement zones) can be delineated in the field using, for example, the fuzzy-k-means clustering technique (Minasny & McBratney, 2002) based on some spatial information such as elevation, soil type, electrical conductivity, and satellite imagery. This approach takes into account the maximum natural variability within an agricultural field. Another way is to use precision agriculture technologies such as yield monitoring, grid-sampling strategies using GPS, and variable-rate devices to collect highly dense spatial data and understand the site-specific effects of the treatments under investigation.

Use Data Analysis Strategies: Interpret and Communicate the Results Effectively

After you have collected the data to answer your research questions, it is time for data analysis and effective communication of the results. One of the critical components of on-farm research is to adequately summarize and analyze study outcomes and effectively communicate results to producers and a broader audience (e.g., agronomists, researchers, funding agencies, and practitioners). Employing a process that uses delineated experimental design methods with replication, randomization, and blocking is crucial. To obtain conclusive results, a minimum of three replications is recommended. These methods allow for identifying and isolating natural variation effects such as topography and soil type for more precise and detectable results from changing agricultural practices. Using the most appropriate statistical analysis and confidence level may help conclude whether the observed differences are due to the treatments or simply a result of chance. Overall, statistics are one of the major aspects that distinguish on-farm research from on-farm demonstrations or variety plots.

Although there are many experimental designs and statistical analysis options for on-farm research, randomized replicated strips trials have been one of the most used experimental designs. One strategy here is to design the strips with double or at least the same width as the planter, spreader, or combine. Randomized complete block design and large side-by-side plots with georeferenced points have also been frequently used. Some studies have focused on assessing the hypothesis testing’s accuracy and bias testing of on-farm experimental designs and statistical parameters. These studies have shown that the on-farm experiments’ structure, experimental design, and estimating method did not substantially affect the overall treatment mean. However, the accuracy of estimation has increased with more replications, and treatment randomization increased the variance of estimated parameters. Split-plot, chessboard, and randomized strips were the most efficient design for two-treatment on-farm experiments. In terms of data analysis strategies, we strongly recommend graduate students who want to work with on-farm research to consider taking statistical and GIS training or courses such as multivariate statistics, design of experiments, and spatial analysis.

"A key point of on-farm research is to translate all the visionary and theoretical science into practical applications."

A key point of on-farm research is to translate all the visionary and theoretical science into practical applications. The importance of communication, extension, and outreach must be viewed as a core value in on-farm research. Involving direct engagement with farmers is vital for the study’s success as well as to enhance adoption. Much more than only using online or printed material, a better communication method can be utilized by implementing different communication instruments such as charts, field days, and demonstrations. Meetings with the producer also help strengthen the understanding of the protocols, goals, expectations, and sharing results with producers, which are the final on-farm research target.

Once an effective communication system is established, many other aspects of sharing results will easily fall into place. To foster that, we recommend students and researchers to accomplish and strive for the following: (1) send summarized reports to producers and team members about the results; (2) hold small meetings with the producer to discuss outcomes directly; (3) keep producers up to date on field visits and activities; (4) hold small-group discussions; (5) organize and participate in field days with on-site demonstrations; (6) foster producers’ curiosity by making them an important component of the research. Becoming an effective communicator takes effort, and by developing these skills during graduate school, students will be working to increase on-farm research performance. To assist with that, the ASA, CSSA, and SSSA (ACS) Graduate Student Committee offers several workshops and webinars to help students improve networking, leadership, and communications skills.

"Becoming an effective communicator takes effort, and by developing these skills during graduate school, students will be working to increase on-farm research performance. To assist with that, the ASA, CSSA, and SSSA (ACS) Graduate Student Committee offers several workshops and webinars to help students improve networking, leadership, and communications skills."

Acknowledge the Limitations of Working with On-Farm Trials: Adjust Expectations Accordingly

Graduate students are often trained to answer highly technical questions through complex study designs. However, conducting on-farm research is a different story. Students need to use a more realistic approach when planning, performing, and communicating the on-farm studies with farmers.

Building trust along the way is a critical and constant process that requires engagement and time. A great way to do that is by inviting producers to meet you in their fields when you are collecting data or doing any activity in their area. It is an opportunity to showcase what, how, and why you are pursuing that research. Also, it is a fantastic opportunity to connect with the producers and start a conversation about their challenges and learn what they have been doing that is working. These actions will show your interest in their challenges and willingness to help producers to overcome them.

Rewards of Including On-Farm Research into Your Project

Conducting on-farm studies move us out of our comfort zone in several ways. It adds an extra layer of complexity because producers can be viewed as an extra project manager, just like our advisers and committee members. Coordinating on-farm research activities requires time, effort, and clear/frequent communication between the researchers and producers. On the other hand, this is a great opportunity to develop skills that we often do not develop when performing traditional research. Finally, cutting-edge solutions for critical topics in today’s agriculture need brainpower that demonstrates discipline, creativity, and a collaborative spirit. Designing, implementing, and communicating on-farm research studies can provide you an avenue to hone these employability skills, positioning yourself to be a great contributor to the agricultural scientific community in your field of expertise and beyond.

Chaney, D. (2017). How to conduct research on your farm or ranch. Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE). www.sare.org/resources/how-to-conduct-research-on-your-farm-or-ranch/

Ketterings, Q., Czymmek, K., & Gabriel, A. (2012). On-farm research (Cornell University Extension Factsheet 68). http://nmsp.cals.cornell.edu/publications/factsheets/factsheet68.pdf.

Kyveryga, P.M. (2019). On-farm research: Experimental approaches, analytical frameworks, case studies, and impact. Agronomy Journal, 111, 2633–2635. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2019.11.0001

Lauer, J. (2012). On-farm testing. University of Wisconsin. http://corn.agronomy.wisc.edu/Management/L016.aspx

Luck, J., & Fulton, J. (2014). Best management practices for collecting accurate yield data and avoiding errors during harvest (University of Nebraska Extension Publ. EC2004). https://extensionpublications.unl.edu/assets/pdf/ec2004.pdf

Minasny, B., & McBratney, A.B. (2002). FuzME version 3.0. Australian Centre for Precision Agriculture, The University of Sydney, Australia. https://precision-agriculture.sydney.edu.au/resources/software/

Mullen, R., Lentz, E., Labarge, G., & Diedrick, K. (2008). Statistics and agricultural research. Ohio State University. https://agcrops.osu.edu/sites/agcrops/files/imce/fertility/Statistics_ag_research.pdf

Nielsen, R.L. (2010). A practical guide to on-farm research. Purdue University Extension. http://www.kingcorn.org/news/timeless/onfarmresearch.pdf

Thompson, L., Glewen, K., Rees, J., Elmore, R., & Burr, C. (2016). Ten steps for on-farm research success. University of Nebraska On-Farm Research Network. https://cropwatch.unl.edu/2016/10-steps-farm-research-success

University of Nebraska On-Farm Research Network. (2021). On-farm research technology guides. https://cropwatch.unl.edu/farmresearch/farm-research-tech-guide

- Carlos B. Pires, Fernanda S. Krupek, Gabriela I. Carmona, Osler A. Ortez, Laura Thompson, Daniel J. Quinn, Andre F. B. Reis, Rodrigo Werle, Péter Kovács, Maninder P. Singh, J. M. Shawn Hutchinson, Dorivar Ruiz Diaz, Charles W. Rice, Ignacio A. Ciampitti, Perspective of US farmers on collaborative on‐farm agronomic research, Agronomy Journal, 10.1002/agj2.21560, 116, 3, (1590-1602), (2024).

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.