Farming in fukushima one decade after nuclear disaster

- One decade ago, on 11 Mar. 2011, a massive earthquake and its ensuing tsunami triggered explosions in three nuclear reactors at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi plant.

- The explosions released radioactive cesium-137 (Cs-137), contaminating the water and soils of Japan’s Fukushima Prefecture.

- In this article, we talk about the science behind Cs-137’s affinity for the clay in Japanese soils and how scientists are helping the residents of Fukushima restore their farmland and recover their livelihoods.

The mechanics of nuclear disaster are complex, but the ensuing contamination is devastatingly simple: something is where it was not meant to be.

One decade ago, on the afternoon of 11 Mar. 2011, a magnitude 9 earthquake struck off the northeastern coast of Japan’s main island, Honshu. The earthquake spawned a tsunami that battered the coastline with waves as tall as 12-story buildings.

Three nuclear reactors were active that day at Tokyo Electric Power Company’s (TEPCO) Fukushima Daiichi plant, about 40 mi from the epicenter of the quake. All three reactors shut down at the first sign of seismic activity, but the earthquake knocked out their power supply; the tsunami took out the plant’s backup diesel generators.

It was a perfect storm. Without power, the engineers at the plant had no way to cool the reactor cores where nuclear fission continues to generate heat long after shutdown. Inside, the water used to cool the units was turning to steam, reacting with the zirconium casing enclosing the uranium oxide pellets in the core and forming hydrogen gas. A spark, and boom: a hydrogen explosion.

The explosions released steam containing water-soluble radioactive by-products of nuclear fission: iodine-131 and cesium-137 (Cs-137). Fortunately, the Japanese government issued evacuation orders for increasingly large areas surrounding the Fukushima Daiichi plant, which prevented many residents from being exposed to excessive radiation. But many evacuees from the vibrant farming villages have not returned home since.

Though the ill effects of Cs-137 are well known (especially when it comes to groundwater contamination), the radioactive isotope presents a uniquely difficult issue for the Japanese government, scientists, and farmers—all because of one particular clay mineral in Japanese soils.

Here, we’ll explore the science behind the intense attraction between Cs-137 and a certain kind of clay found abundantly in Japanese soils. We’ll hear from Japanese soil scientists and agricultural engineers who are still decontaminating the rich farmlands of Fukushima. Finally, we’ll see how, 10 years after nuclear meltdown, residents and non-profit organizations are rebuilding and innovating to keep the farming villages of Fukushima alive.

Global Collaboration, Annual Meeting

After the nuclear disaster at Fukushima Daiichi, the Japanese government found irradiated cesium in the water supply of Tokyo. One group documented radiocesium in the placentas of mothers who gave birth in the months after the explosions. The release of radioactive cesium from Daiichi cooling operations into the ocean impacted Japanese fishing and fisheries where radioactive specimens were caught until 2015.

When Cs-137 is ingested, that poses the greatest threat to human life. This most frequently happens when the isotopes make their way into water. Cesium is similar in size and chemical properties to potassium, which means that plants and animals can take it into their bodies through pathways that typically harness potassium.

In Japan, Cs-137 was not in the water supply for long. Instead, it’s the fertile topsoil of Fukushima Prefecture (equivalent to a state in the U.S.) that has suffered the most.

“We didn’t know anything about what was going on,” says Kosuke Noborio, a 32-year member of ASA and SSSA and professor at Meiji University in Tokyo. “What we did know was from nuclear bomb tests where cesium was released into the atmosphere. They found Cs in the soil from bomb fallout, but Fukushima had 1,000, even 10,000, times as much [Cs as] the regular fallout.”

By 2013 at the ASA, CSSA, and SSSA Annual Meeting in Tampa, FL, Noborio chaired a session where his colleagues and students presented their research on the soils of Fukushima. A wet-bench soil chemist named Daniel Ferreira perked up his ears.

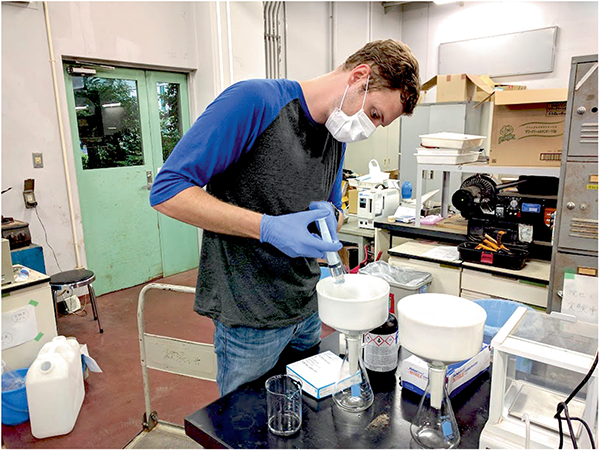

“As I was watching presentations, I realized the process of adsorption of cesium to vermiculite is very similar to the way sodium interacts with zeolite, another class of clay mineral,” Ferreira says. He documented the affinity of sodium ions for zeolite minerals for his doctoral dissertation. “I knew there must be something I could do to help, so I talked to Dr. Noborio after the session. He invited me to Japan in 2016 as a visiting scholar. I met the farmers. I saw the damage in Fukushima. I saw the soil.”

Since then, Ferreira and his graduate students have been working to understand just how Cs interacts with vermiculite and trying to find ways to remediate the soils of Japan.

A Terribly Strong Attraction

Vermiculite is a 2:1 clay that forms in the soil as micas and chlorites weather (https://bit.ly/393oumI). The vast majority of the time, vermiculite’s high cation exchange capacity means it serves as a great source of monovalent and divalent cations that plants need to survive, like potassium or magnesium.

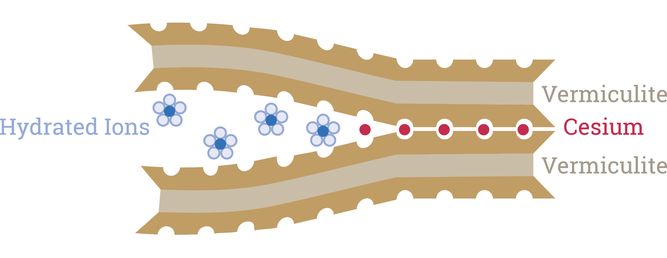

Historically, Fukushima’s rich topsoil, which contained up to 35% vermiculite clay, served as incredibly fertile ground for farmers. But when Cs-137 came into contact with vermiculite, it made its way into the interlayers where hydrated ions like K or Mg typically stay.

Unlike K+ or Mg2+, once Cs ions enter the interlayers of vermiculite, they aren’t available for uptake by plants. In fact, the Cs doesn’t really move…at all.

Now we’re going to take a detour into the land of wet-bench soil chemistry to understand why Cs stays put.

In 2017, Ferreira and his then-graduate student, James Thornhill, set out to test the strength of the affinity of vermiculite clay and Cs in a set of experiments they published in the Journal of Environmental Quality in 2018 (https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2018.01.0043). The duo used cesium chloride (with the stable isotope of Cs) and lab-grade vermiculite soaked in varying levels of acidic solutions.

“When we look at adsorption as a function of pH, the role of hydrogen is as a competitor for that adsorption site on the mineral,” Ferreira says. “Essentially what we were doing was putting Cs into different battle scenarios to fight hydrogen for those sites.”

Testing the affinity of an ion for a mineral like this demonstrates just how tightly that ion will hold on. For example, the affinity of K+ for a similar mineral, ferrierite, tails off at pH 3.0.

What Thornhill and Ferreira found surprised them.

“We went all the way down to pH 1. You’re talking battery acid, at that point, and the Cs adsorption didn’t go to zero,” Ferreira says. “Not even close to zero.”

How does that happen?

It turns out Cs and vermiculite have some interesting compatibilities that make it incredibly difficult to pull them apart.

In vermiculite’s interlayer, oxygen atoms stick off the mineral surface in a way that creates ditrigonal siloxane cavities. If you look at a ball-and-stick model of the molecular composition of vermiculite, you’d see these little indentations where the molecular clouds of the oxygen atoms don’t overlap.

Cs is the perfect size to shimmy into those little cavities. Once it does, it pulls the clay layer together, sealing it off like closing an egg carton around an egg. A perfect fit!

Ferreira and Thornhill measured this using X-ray diffraction of vermiculite with either cesium or water in its interlayer. They found that pure vermiculite soaked in water has an interlayer of 3.25 angstroms while the cesium chloride–soaked clay has an interlayer of a mere 1.20 angstroms. Angstroms are equal to one hundred-millionth of a centimeter—a measurement on the atomic level. In effect, the team showed how Cs binds both sides of the clay interlayer so tightly that it decreases the gap by two-thirds, effectively sealing it off.

This is both a blessing and a curse. On one hand, Japan avoided the wide-scale groundwater contamination that is so harmful to all forms of life. On the other, the country is still faced with the overwhelming task of removing irradiated soil with a 30-year half-life to prevent cancer-causing radiation exposure for the residents of Fukushima.

As an aside, the same characteristics that make vermiculite and Cs bind so tightly are used by nuclear physicists and engineers to remove radioisotopes from contaminated water. One common method of cleaning up water contaminated with Cs-137 is by running it through filters made with zeolite—the clay mineral that Ferreira worked on for his Ph.D. research.

Now, Ferreira and his current graduate student are working to uncover a chemical compound capable of breaking the strong attraction between cesium and vermiculite, replacing the interlayer cation with Mg and removing the Cs in a precipitated salt. If Ferreira can find a viable, affordable chemical compound, he could help the Japanese government reduce the amount of highly radioactive waste material they need to dispose of and decrease the radiation of the bulk of the topsoil to a degree that allows its safe disposal in a landfill, instead of a specialized containment unit.

Soil Decontamination in Iitate Village

Let’s leave the land of wet-bench chemistry and look instead at the happenings in Fukushima over the past 10 years.

Masaru Mizoguchi, a professor of global agricultural science at the University of Tokyo and 29-year member of ASA and SSSA, saw Iitate Village on the news just after the nuclear disaster. Mizoguchi wanted to help, but he needed a closer look. He invited his colleague, Noborio, to go to Iitate Village.

At the time, no one really knew what was going on. It took the Japanese government nearly a year to begin decontaminating the soils of Fukushima.

“The Japanese government came up with three approved decontamination methods,” Mizoguchi says. “But they were decontaminating such large areas—it took the government a long time, and the farmers were just waiting. They didn’t have the equipment to do it. I wanted to come up with methods the farmers could do themselves.”

The government’s primary decontamination method was scooping up the top 5–10 cm of radioactive topsoil, bagging it, and moving it to temporary storage areas. It was a time-consuming, expensive, laborious process, and there was no permanent solution for storing the now-concentrated piles of radioactive soil.

Plus, just after the accident, Noborio described how the hooves of wild boars and the deep root systems of heavy weeds that grew on the unmanaged farmland mixed cesium deeper into the soil layer than anyone anticipated.

So Mizoguchi started working with farmers to test alternatives. In one method, Mizoguchi helped farmers remove frozen topsoil in big swaths, like peeling an orange or cutting turf. Though the method worked well to cut back radiation, it was difficult, time-consuming labor and still left farmers with the problem of finding somewhere to dispose of the contaminated soil.

Changing tack, Mizoguchi developed another method in which farmers flooded their contaminated rice paddies, then stirred up the soil beneath with a common tool: a weeder. Like a rototiller, the weeder mixes up the top layer of soil—here, churning it into increasingly muddy water. Sand and silt quickly fall out of suspension in the paddy water, but clay particles remain suspended for a longer time. Farmers pushed the contaminated water out through holes in the dikes around their paddies, removing the cesium-vermiculite complex in the process.

Finally, he tried a third method: burial.

“If we cover the cesium-contaminated soil with 50 to 100 cm of uncontaminated soil, we cut radiation by 1/1000,” Mizoguchi says.

In all three cases, the same quality that makes cesium so dang difficult to get rid of also works in favor of hands-on decontamination methods. If you move the clay, you move the Cs-137, and it really isn’t going anywhere.

Mizoguchi ground-truthed this claim using a device he created out of PVC pipes with Geiger-Muller tubes (which measure all different kinds of radiation) threaded inside them. He buried these pipes in long-term sites and took measurements of gamma radiation over the course of several years. He found that the topsoil was at safe levels of radiation, and the cesium was not moving any deeper into the soil, nor was it dissipating. Instead, the level of radiation decreased as predicted by its half-life. It’s important to note that this consistency means that Cs-137 is not returning to groundwater supplies. The high affinity of vermiculite for the element prevents it from moving out of the clay layers.

Mizoguchi’s hands-on decontamination efforts are a sign of hope for farmers in Fukushima, but they’re facing another issue, too: the movement of contaminated soils into decontaminated zones.

Cesium Moves Down Mountains

Iitate Village is sheltered by the soft, low, tree-covered Abukuma Mountains. They’re much of the reason Fukushima was so heavily impacted by the Cs-carrying steam from the Daiichi plant. Iitate Village was on the windward side where rain fell before the mountains created a rain shadow that buffered the land farther north and west from nuclear fallout from the irradiated steam.

Though decontamination efforts in the farmland of Fukushima Prefecture have removed the bulk of Cs-137 from the land, little effort has been taken to remove Cs-137 from these mountains.

When Taku Nishimura met with one of the prominent farmers in Iitate, the farmer asked: is contaminated soil moving off the mountains, into the streams that supply his irrigation water?

Nishimura, a professor in the graduate school of agricultural and life sciences at the University of Tokyo, began to investigate. In 2014, he led a team that sampled soil at varying locations on the slope of a mountain outside the village. They expected to find that soil lower down on the slope had higher levels of radiation, due to increased levels of Cs migrating downward with the soil sediment and rainfall.

Instead, the group found that unexpected places showed increased levels of radioactivity deeper in the soil profile. These locations all had higher levels of leaf litter than those where Cs-137 remained higher up in the soil profile. Nishimura wondered: does increased organic carbon content contribute to the movement of cesium downward in the soil profile?

Nishimura took weathered granite soil from the forest back to the lab. There, his team ran cesium solutions at two different concentrations with and without dissolved organic matter in the form of leaf litter. They found that at high concentrations, the leaf litter had no impact on the amount of cesium that moved through the column. But at low concentrations, similar to what is found in the forests of Fukushima from the nuclear fallout, leaf litter applied before or at the same time as the cesium solution increased the amount of cesium that traveled through the soil column. Nishimura suspects that organic matter decreases the availability of binding sites in the clay, moving more Cs through the soil without binding to vermiculite.

Though that explains the strange findings in the soil profile, it still doesn’t quite answer the farmer’s question. How much Cs is in the streams running from the forested catchments above his fields?

Next, Nishimura and his colleagues used a simulation tool developed by USDA to pinpoint locations in the forest that would supply sediment to streams that move down into the village.

“The forest is about 55 hectares, but the actual sediment source is quite small,” Nishimura says. When his team documented radiation, they found that the average amount of radiation from Cs-137 in the stream in 2013 was 1.0 MBq (megaBecquerel) per square meter. For context, 1.0 MBq means there are 1,000 atoms disintegrating per second in the stream. This measure, though, tells us little about radioactive dose—that is, the amount of radiation exposure you would receive from being near the radiation source.

“We had one interesting result. When the sediment concentration was high, the Cs concentration was almost always the same, but when the sediment concentration was low, the fluctuation in Cs was quite large,” Nishimura says.

The researchers discovered two “cesium balls” in their low-sediment samples from the stream during rainfall events in 2018. These microparticles were tiny complexes of Cs, iron, zinc, and silicon. Though rare, the microparticles emitted a much greater amount of radiation than sediment alone and present the same recontamination issues as the movement of clay off the mountains.

Nishimura suspects that these microparticles were formed within the nuclear reactor, where the concrete walls and reactor itself would have supplied sources of zinc, silicon, and lead that complexed with the cesium. His team is continuing to monitor the transport of soils in Fukushima and hopes to set up more test sites in different catchment areas this year.

Revitalizing Agriculture in Iitate

So far, we have walked through the Cs–clay love story, through decontamination, and through transport of contaminated soils into cleaned-up areas. But there’s one important thing still to mention: because the clay plays such a big role in soil fertility, all these decontamination efforts create massiv

e issues for the farmers who returned and are trying to grow crops. In areas where the Japanese government removed irradiated topsoil, they replaced it with crushed granite.

Noborio is helping farmers tackle soil infertility with new, innovative forms of agriculture. For example, Noborio’s recently retired colleague donated money to create an experimental fertigation greenhouse in Iitate Village. The fertigation method supplies water containing fertilizer with twice the necessary level of potassium to prevent vegetables from taking up any residual Cs left in the soil.

Plus, the fertigation system is cloud based and automatically regulates water flow to the plants based on the weather, water content in the soil, and evapotranspiration of the plants in the greenhouse. The team recently published a calibration study of the automated fertigation method in a Japanese journal, examining stemflow—the flow of water from the soil through a plant—in bell peppers grown in their experimental greenhouse.

“We’ve grown bell pepper, lettuce, and tomatoes in the summer, and spinach in the winter,” Noborio says. “We’re introducing a whole new agricultural practice. Before the accident, farmers used greenhouses for flowers, not vegetables. We can expand agriculture here.”

Likewise, Mizoguchi is helping the farmers of Iitate Village expand agriculture through integrated communication technology (ICT). For example, he rigged one farmer’s rice paddies with Wi-Fi-enabled cameras and remote-controlled gates to regulate the amount of water in the paddy. The farmer can see the water levels using the camera and open or close the gate to let more water in, if need be—“All from his iPad!” Mizoguchi exclaims.

In 2011, Mizoguchi founded a research group, called Fukushima Reconstruction Agricultural Engineering, dedicated to bringing cutting-edge technology to farmers in Fukushima. Their goal is not just to help current farmers, but to appeal to younger working people, too.

Though Mizoguchi and Noborio are finding new ways to overcome soil infertility, there’s still the question of selling products from Fukushima. Urban residents are often wary of consuming vegetables, rice, or meat raised in Fukushima. Stigma surrounds the area despite rigorous testing that shows no Cs-137 contamination.

In fact, exposing produce to gamma radiation produced by Cs-137 is a fairly common method of removing foodborne pathogens. There are no known harmful effects for consuming vegetables exposed to gamma radiation (https://bit.ly/3cq4mNZ). Radiation’s harmful effects manifest in organisms with longer life spans where cellular mutations accumulate and increase their risk of cancer.

“People are scared about the food, about taking in the cesium,” says Thornhill, who spent three months in Japan in 2017. “When I told my host family I was going to Iitate Village, they told me, ‘Whatever you do, don’t eat the food.’ I was able to come back and tell them it’s been tested, it’s safe to eat.”

Did it convince them?

“They were set in their ways—it was going to take someone with more authority than me to tell them it’s safe,” Thornhill says.

This is exactly what researchers are setting out to do. As part of a study in the Journal of Water, Land, and Environmental Engineering (published in Japanese), Noborio and his colleagues collected survey data from city residents in Yokohama, asking them about their willingness to consume produce from Fukushima. More than 80% of urban residents agree that they want to buy agricultural products and support farmers, but only 50% would like to purchase vegetables from Iitate Village, a known site impacted by the nuclear disaster. Interestingly, nearly 75% of respondents agreed that they would buy vegetables produced in collaboration with a university.

One of Noborio’s colleagues is creating small labels to affix to products from the area, including fresh produce and pickled vegetables, indicating that researchers collaborated with farmers to grow the produce. So far, they’ve found that the label really does help consumers overcome their biases.

Mizoguchi has also had great luck working with farmers through the nonprofit, Resurrection of Fukushima, to sell alternative products. For example, Mizoguchi has collaborated with farmers and brewers to create a sake—an alcoholic fermented rice beverage—that won the Japan Sake Awards for seven years running.

Their newest release is available now. It’s aptly named “Like a Phoenix” after the mythical bird that rises from the ashes, reborn from its own destruction.

The farmers in the region also raise famed Wagyu cattle—the kind that produce meat that fetches as much as $200 per pound in the United States.

In another ingenious use of materials grown in Fukushima, an organization called METER collaborated with the University of Tokyo and the Resurrection of Fukushima nonprofit to produce a book, titled Made in Fukushima. The book is printed on rice paper from rice grown in Fukushima’s decontaminated fields. Written in English and translated into Japanese, the book is available for pre-order (https://madeinfukushima.com).

It’s all these efforts, beyond understanding the science behind the nuclear contamination, that really bring life back to the region. The tireless innovation and compassion from Noborio, Mizoguchi, and all their colleagues and nonprofit contacts is truly touching.

“It’s really this nonprofit work that Dr. Noborio is doing that helps the farmers in Fukushima,” Ferreira says.

When I asked Noborio how he’s feeling about his work with people of Iitate Village after a decade, he took a slow, deep breath.

“I don’t know,” he said. “We just want them to feel they’re not alone…we’re here for them; we’re with them for this recovery. It’s the best we can do.”

Learning More, Preparing for the Worst-Case Scenario

On 13 Feb. 2021, just shy of a decade after the disaster, Japan was hit with a 7.3 magnitude quake—an aftershock of the same earthquake that caused the disaster at Fukushima Daiichi. At the time of publication of this article, Japanese officials have not identified any irregularities in their nuclear power plants, but residents along the coastline are wary. Many have already evacuated for higher ground, remembering the tsunami that caused such devastation one decade ago.

Both the initial disaster and its ongoing aftershocks stand as a clear warning to be prepared as there is so much we don’t know. Though the scientists and nonprofit organizations alike have done awe-inspiring work, all of it is a product of not knowing the impact of one element’s interaction with one particular soil mineral.

“The government did not prepare for the worst case. The company did not prepare,” Noborio says. “In Japan, people avoid talking about the worst case because they think if they talk about it, it may actually happen. We need to change that.”

Fukushima serves as a poignant reminder of the way technology can help us, but also how it can hurt us. A massive earthquake, the overpowering force of a tsunami, and the breakdown of all the fail-safe mechanisms designed to prevent disaster, and you have the makings of a 300-year problem.

However, the resilient, persistent efforts of scientists to help farmers return to their homes and recreate their livelihoods shows that we can do great things if we work together.

Dig Deeper

Interested in learning more? Our podcast, Field, Lab, Earth, will host an interview with Dr. Dan Ferreira on 5 March where we discuss the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster, the impact of the fallout on the local soils, and their road to recovery. Find us at https://fieldlabearth.libsyn.com or through your favorite podcast provider. Subscribe for free to never miss an episode. CEUs available.

In March, the Societies will also feature two blog posts about Fukushima research: How Is Erosion Affecting the Recovery of the Fukushima Area? (available at https://soilsmatter.wordpress.com) and What Are the Long-Term Effects of the Fukushima Disaster on Local Agronomy? (available at https://sustainable-secure-food-blog.com/).

In November during this year’s ASA, CSSA, and SSSA Annual Meeting in Salt Lake City, UT, there will be a session titled, “Dealing with the Fallout of Fukushima—10 Years of Soil Contamination.” More details will be available later in the year.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.