Bringing cattle onto cropland in the northern great plains

Can Grazing Cover Crops with Cattle Benefit Producers and the Soil?

- Integrated crop–livestock systems (ICLS) bring cattle and cropland together, often incorporating other practices like cover crops, no-tillage, and diversified crop rotations.

- New SSSAJ and AGE studies look at the soil health and water quality of short- and long-term ICLS, including cover crops and livestock grazing in the Northern Great Plains.

- For producers, livestock grazing could be a means of increasing cover crop adoption and biodiversity on traditional corn–soybean cropland with no negative effects on soil health or water quality under proper management.

If we can’t change the acreage we have to farm, how do we enhance production?” asks ASA and SSSA member Sandeep Kumar. “I think the only option is to diversify the same acreage and increase both soil health and crop production.”

Integrated crop–livestock systems (ICLS) may be a great answer to diversify crop rotations while supporting the financial goals of farmers and producers. In the Dakotas, these systems involve bringing cattle onto cropland to graze crop or cover crop residue, whether directly or hayed. But how do these systems impact soil health and water quality?

Kumar is the project director for a USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA-NIFA) Coordinated Agricultural Project (CAP) grant1 to examine ICLS in practice, from all angles. His project involves five institutions, roughly 30 researchers and graduate students, and countless volunteers.1

The team studied the soil health, economics, nutrient cycling, greenhouse gas emissions, and water quality in ICLS to see how we can increase our resiliency, food security, and biodiversity by bringing livestock onto cropland. Two recent publications—among many others—were born of the project.

First, we’ll look at a new study in the Soil Science Society of America Journal (SSSAJ) detailing the impacts on soil health in long-term ICLS compared with both short-term ICLS and grazing. This study stacks practices including cover crops, residue grazing, and no-till management (https://doi.org/10.1002/saj2.20214).

Then, we’ll dig into the impacts of cattle, cover crops, and grazing on water quality through simulated rainfall tests, published in Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment (AGE; https://doi.org/10.1002/agg2.20129).

Finally, we’ll hear from an outstanding producer who diversified his land use and integrated grazing and cover crops before it was cool. He’ll give us perspective on why you might try out something risky and new to keep your soil healthy and your production sustainable.

Production in the Northern Great Plains

Diversity in crop production is sorely lacking in the Northern Great Plains, an area spanning the Dakotas, Nebraska, Montana, and parts of the prairie provinces of Canada. As of 2017, 75% of the planted acres in the Midwestern United States (including the U.S. side of the Northern Great Plains) were traditional corn–soybean cropping systems, according to the USDA. Between 2006 to 2011, producers converted more than 1.3 million acres of native grassland to cropland in the Northern Great Plains as commodity crop prices increased for corn and soybean in the late 2000s.

Meanwhile, the Dakotas have plenty of livestock. As of 2017, South Dakota tallied nearly 4 million head while North Dakota harbored just less than 2 million.

Producers typically manage these cattle using a combination of pasture grazing and feeding cattle on dry lots in the winter, but the cost of winter feed is prohibitive. North Dakota State University Extension estimates that 70% of the average producer’s feed costs pile up in the winter with the other 30% attributed to pasture and summer grazing. Much of the costs come from the labor and machinery involved in haying, moving, and storing feed for the winter. Plus, it’s often less nutritious for cattle than grazing.

Bringing cattle onto cropland to graze corn and soybean residue after cash crop harvest is one way to mitigate those feed costs. But another is planting cover crops. In an ICLS, these practices (plus, ideally, no-till management), stack to create a system that increases crop diversity, incorporates nutrients from livestock manure and urine, and cuts back on feed and cover crop costs for the farmer. In fact, a major benefit of integrating livestock into agricultural systems is mitigating the costs associated with establishing and terminating cover crops, the University of Nebraska–Lincoln found.

“It’s an ecological concept: if you increase the diversity in the system, you’re likely going to increase its stability and its resilience,” says Jess Soule, associate director for sustainability research for the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association. “It can take more time, more labor, but there’s a lot of ecosystem services that come from bringing cattle onto cropland.”

Intuitively, the system makes sense. But research on long-term ICLS is lacking because managing cattle and cropland is difficult—one producer will have a hard time doing both, and sustainable management is very site specific. What works in the Northern Great Plains is no template for the southern United States, Europe, or Brazil.

“You have to take an adaptive management approach when you work with these systems,” says SSSA Fellow Mark Liebig, co-author of the AGE study and co-principal investigator of the USDA CAP project. “If something goes wrong—if it becomes dry and your cover crops don’t grow—you have to have a card to play down the line, so you can keep the system functioning. It’s what farmers have to do all the time.”

It was this lack of research and documentation on complex systems that have such potential for farmers and for biodiversity that drove Kumar to develop the project encompassing these studies on soil health and water quality.

“We wanted to extend the research,” Kumar says. “Farmers manage these production systems on a thousand acres or more—how do these systems work on a larger scale?”

Cattle, Cover Crops, and Soil Health

If you really want to see how soil health changes, you need more than just a few years.

So Sandeep Kumar and his then-graduate student (also a member of the Societies), Jashanjeet Dhaliwal, turned to extension agents to find out which producers in the Dakotas have been using cattle on their cropland. They chose three producers who have been using cows to graze corn and soybean residue for more than 30 years.

They then put together a study to examine both long- and short-term ICLS sites to compare their impacts on soil physical and hydrological properties. Dhaliwal and Kumar selected fields under long-term ICLS management that neighbored other fields under traditional corn–soybean cropping, with no grazing.

“These plots were, at most, 10 ft apart,” Kumar says. “You could stand on one side of the fence and look out at both fields—one with crop residue and no-till, the other under conventional management.”

With sites selected, the team started managing the plots in 2016. On both the long- and short-term sites, they implemented a three-year rotation: corn, soybean, and then a cover crop blend of grasses, legumes, and brassicas. At two sites, they planted oats after soybean harvest. In all four ICLS treatments, the producers brought Aberdeen Angus cattle off summer pasture in November to graze residue until March, based on forage availability.

In 2019, the researchers sampled the soil, testing for soil organic carbon, soil bulk density, water infiltration, and water retention.

Compared with control sites with no grazing, soil organic carbon was higher by 20–26% and bulk density was lower by 18–37% at long-term ICLS sites. The team also found that long-term ICLS increased the porosity of the soil and improved both its infiltration rate and soil water retention. They didn’t see such dramatic differences at the short-term site, but there were no negative effects, either. Including cattle grazing did not increase compaction or decrease soil health indicators, which is a common concern for producers trying out these systems.

Including cattle, the authors posit, increased soil organic carbon over time as their hooves incorporated both residue and excreta into the soil—incorporating manure can actually reduce the soil’s compactibility. The cattle also stimulated root growth through grazing. With the study’s grazing rotations, which moved cattle every 6–10 days, the team found no negative effects on soil health.

Were the researchers surprised?

“Honestly, no,” Dhaliwal says. “We were looking at the cumulative effects of the last 30 years in those fields. We expected to see changes in soil organic carbon. We didn’t see any differences, really, in the short-term sites—it takes time to improve your soil. But we have the evidence now that these systems are good for the long-term sustainability of soil health.”

Water Quality

At the USDA-ARS’s Northern Great Plains Research Laboratory, scientists have been parsing out the effects of long-term ICLS management on the land since 1999.

“This study is focused on reducing feeding costs for livestock producers in the Northern Great Plains,” Liebig says. “Over time, we really caught onto the idea of sustainable intensification; of trying to increase production per unit area.”

Liebig, a USDA-ARS research soil scientist, is among the team managing the long-term site with grazing and a three-year no-till rotation of crops typically utilized by local producers. Though management has changed a little over time, the current rotation includes intercropped corn and soybean, then spring wheat interseeded with a cover crop mix, and a third year of perennial cover crop regrowth.

The team had never looked at ICLS impacts on water quality from surface runoff and soil infiltration. Part of the reason is the sporadic nature of rainfall in North Dakota. Annual precipitation ranges from 13 to 20 inches a year with June as the wettest month on average. But it’s tough to be ready when rain comes calling. If you could be absolutely certain about the next rainfall event, you might be able to sprint out to the field, set everything up on your plot, infiltrometer in place, collection bottle poised, and collect data…for a single trial.

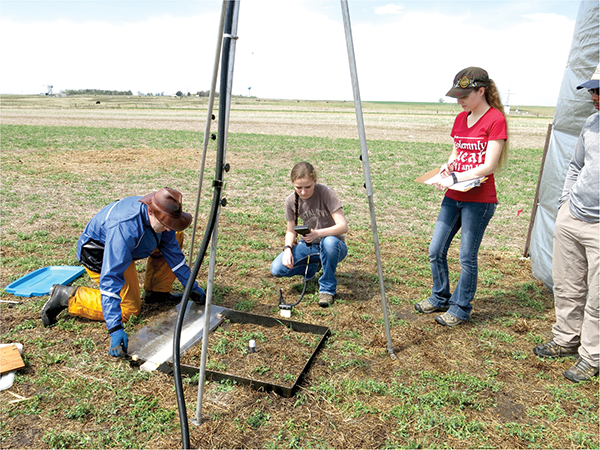

The team decided to create their own rain instead, and brought SSSA member Derek Faust in to manage that. Faust was fresh from a doctoral program at Mississippi State University and had experience using simulated runoff events to test water quality.

For the study published in AGE, Angus yearling cattle grazed either grass pasture, cover crops, or wheat and the relationship between vegetation type and water quality was compared. Cattle grazed all three vegetation types in the fall of each year with portable electric fences to control grazing locations and a stocking density of about one yearling per acre.

Rain was created both before and after grazing using a tripod setup with a special sprinkler head attached and calibrated at a rate simulating an intense downpour.

“We’re talking a 50-year rain event, here,” Faust says. “It’s the kind of rainfall we would expect to see under future climatic conditions.”

The researchers and some willing volunteers huddled near the simulated rainfall for 30 minutes, collecting piezometer data from below the ground and sampling any surface runoff in a bottle. They ran simulations twice for each site and collected all their data within one day for each treatment.

After all that work, they analyzed runoff and infiltration samples for nitrate-N, ammonium-N, phosphate-P, and total suspended solid concentrations. They found that surface runoff of nitrate and ammonium were higher in both wheat and cover crop phases compared with pasture. They also found that there was significantly greater pre-graze runoff of ammonium, nitrite, and phosphate compared with post-graze.

“When you look at the literature, pretty much every study says that grazing is not a good thing for water quality,” Faust says. “But we found that our post-graze water quality was better than pre-graze. And the reason could be, in part, that we had to measure post-graze in the spring.”

North Dakota typically has a great deal of snowpack. Cattle were out grazing residue until November or early December each year, and running rainfall simulations in those temperatures is a pretty good recipe for frostbite and damaged equipment.

“We think we might have had some nutrient uptake by vegetation in the early spring or had some runoff with the snowmelt,” Faust says. “But we were really excited to see that bringing livestock in isn’t impacting water quality like we thought it might.”

With these positive findings for both soil health and water quality, ICLS could be a great option for producers in the Northern Great Plains looking to diversify their operations, buffer their expenses, incorporate cover crops, improve their soil health, and increase their resiliency. Why aren’t more producers giving it a try?

Getting Practical

“There’s nothing on a ranch—or in life—that’s black and white,” Jerry Doan says. “It’s gray, it’s holistic, and it’s never perfect.”

Doan is a fourth-generation rancher on Black Leg Ranch, homesteaded just off the Missouri River in the Dakota Territory by Doan’s great-grandfather in 1882. Today, the ranch is home to herds of cattle and buffalo, cropland, and pasture. Doan’s children came home after college and diversified the operation—one runs a brewery, another a wedding venue, and a third, hunting expeditions. Their agritourism operation has hosted people from all 50 states and 40 countries. The cherry on top is Black Leg Ranch’s induction as a national winner of the Environmental Stewardship Award Program in 2016.

Black Leg Ranch wasn’t always like this.

“I’m old enough, I went through the ‘80s and I watched a lot of the people I admire—the people I thought had it made—go broke,” Doan says. “We had to do something different to survive. Our two main goals were bringing profitability back to the ranch and improving our quality of life.”

The Doan family started running livestock on their marginal lands. They brought grazing back on their sandy plains, increasing biodiversity and wildlife. They cut back on feed costs by selecting for smaller cattle, and they started partnering with their neighbors to come in and lease out cropland. There, they plant cover crops and graze livestock.

“We used to farm that ourselves, but the equipment was killing us,” Doan says. “It was just too much risk, so we brought on some people to share it. We dictate what they plant, when they plant, how they plant, and we have a cover crop mix with 22 different species in it—that helps our soil health, gives our livestock something to eat, and propagates wildlife.”

At one point, Doan noticed the cattle were really rough on Long Lake Creek, a tributary of the Missouri that runs through the ranch. So the family fenced it off and piped water in for the cattle instead, only allowing the cattle to graze near the creek periodically for very short durations.

“That creek is drop-dead beautiful now—there’s wildlife everywhere,” Doan says. “But if we weren’t paying attention, you know, you can ruin those watersheds. We need to pay attention. We need to do our part, and it takes time.”

As for quality of life? Well, Doan’s three sons and daughter (and their various “out-laws”) are back on the ranch. Because Doan switched to later calving, started selecting for smaller cows, and moved to grazing as a primary source of cattle feed, he spends less time calving and haying and has more freedom to see his kids and grandkids.

“Working with your family can be tough. Sometimes you show up to a business meeting, and somebody’s still mad about the marbles somebody else stole 10 years ago,” Doan says. “But my kids reinvigorate me. Their energy, their excitement fired me up again. And I’m going to turn this place over to them in better shape than I got it.”

Black Leg Ranch is just one example of how producers can make ICLS work on their land in their area of the world. Black Leg Ranch makes it look easy, but making changes can be risky.

Jordan Cox-O’Neill, who recently received her doctorate from North Carolina State University, ran a three-year ICLS study on her family’s land in North Carolina. She has firsthand knowledge of how tough it can be to set up a whole new enterprise.

“When you set cattle up on cropland, you have to make sure you have fence and water,” Cox-O’Neill says. “For just our two locations, that was about $30,000. We had a couple of producers who were interested in working with us, and we had cover crop seed for them, but they just couldn’t foot the bill for the fence.”

Cox-O’Neill also mentions an aspect of holistic systems that’s easy to overlook: communication.

“The biggest challenge is that you can’t do everything. Someone has to look after the livestock; someone has to manage the crops,” she says. “It takes a lot of coordinating, collaborating, and communicating. That can be really tough.”

The Benefits of Risky Research

Bringing crops and livestock into one system presents challenges to producers and scientists studying these complex systems. There’s a ton of moving parts, but these studies show the benefits of research collaborations that take on tough subjects. With the help of producers like those in the SSSAJ study who’ve spent 30 years grazing residues, the example of conservation-minded operations like Black Leg Ranch, and the dedication of research teams willing to take on intricate studies, we have new support for systems that can help solve multiple problems on crop and grazing land.

“As researchers, we have the ability to take risks that farmers may not be able to take,” Faust says. “We can try out these systems, find out if they work from a research perspective, and give that information to farmers. The payoff can be huge for producers—that’s why it’s so important to support agricultural research.”

Altogether, ICLS in the Northern Great Plains could be a great place to look to sustainably intensify agricultural systems. The research supports the long-term benefits to soil health, and water quality may not suffer from cattle grazing under conditions that manage their movement from pasture to pasture.

Dig Deeper

“Hydro-Physical Soil Properties as Influenced by Short and Long-Term Integrated Crop–Livestock Agroecosystems” in the Soil Science Society of America Journal: https://doi.org/10.1002/saj2.20214.

“Water Quality of an Integrated Crop–Livestock System in the Northern Great Plains” in Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment: https://doi.org/10.1002/agg2.20129.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.