From asphalt to ecosystem

Students help align staff headquarters with core values of the Societies

Students from the University of Wisconsin-Madison are partnering with ASA, CSSA, and SSSA to transform their asphalt-heavy headquarters in Fitchburg, WI into a science-based model of green infrastructure that better reflects the Societies’ sustainability values. Through hands-on soil testing, spatial mapping, and ecological design, the project is turning stormwater challenges into an opportunity for education, ecosystem restoration, and long-term community impact.

The American Society of Agronomy (ASA), Crop Science Society of America (CSSA), and Soil Science Society of America (SSSA) have long advocated for sustainable, eco-friendly practices. However, the current landscape surrounding the Societies’ headquarters site in Fitchburg, WI—marked by cracked pavement and excess stormwater runoff—doesn’t exactly evoke a philosophy of environmental responsibility and stewardship.

The typical suburban office space, while framed with conventional landscaping, is currently much more of an asphalt parking lot than a functional ecosystem. To better reflect the Societies' core values, ASA, CSSA, and SSSA began a collaboration with an undergraduate capstone class in the Department of Soil and Environmental Sciences (SES) at the University of Wisconsin–Madison (UW-Madison). This collaboration spurred the involvement of two other UW-Madison student groups, all led by SSSA members and affiliates. The three groups have begun a science-based redesign of the property that will continue this spring.

The senior capstone class, led by longtime SSSA member Dr. Nick Balster, was tasked with conducting soil health tests and suitability analyses of the site for green infrastructure—practices that use plant and soil systems to improve stormwater management. The second group, a cohort of master’s students in UW-Madison’s Environmental Observation and Informatics (EOI) program, was tasked with spatially mapping the soil data acquired by the capstone class and creating an interactive, multimedia map to share this work. These data and maps will further inform and help initiate concept designs for the site, which will be done by an undergraduate landscape architecture intern working with a local small business (Silvernail Studio for Geodesign). This last group, with expertise in green infrastructure and ecological design, will formalize a design based on the scientific findings from the SES capstone class.

The project, which started in the fall of 2025, will continue throughout 2026 as the design is finalized and installation is underway. For this article, we’ll focus mainly on the work done by the SES capstone class. Later in the year, we will dive deeper into the work of the EOI students and the landscape architects as their work continues to unfold.

Practical experience for students in soil and environmental science

Every year, senior undergraduates in UW-Madison’s College of Agricultural and Life Sciences must complete a capstone course that integrates fundamental knowledge from their degree into a “real-world” experience. This year, Balster’s capstone class is made up of nine students majoring in soil or environmental science.

Balster has taught the capstone course and facilitated group projects for the past 20 years. Some example projects from the past include assessing the leaching potential of nitrate into wells as well as soil properties of K-12 school gardens. Through these avenues, his students learn that soil science can be applied across multiple disciplines beyond traditional fields like agriculture.

“Years back, we did a fantastic, super interesting study on green graveyards where the class determined the best places to bury the deceased in the ground based on existing soil properties of the site,” says Balster, adding that he even brought in forensic scientists as key guest speakers. Before this class, his students had never realized soils could play such an important role in a common cultural practice.

This year, Balster notes that his current class had the chance to explore another non-traditional career in soil science through urban soils. Urban soils are unique. “They're human modified. That presents a big challenge to their use,” says Balster. “And with that human modification comes unexpected soil properties and processes.”

"Soils are foundational to the aesthetics and functionality of environments. And if you don't know the media you're dealing with, the aesthetics and the functionality are compromised."

Human “artifacts,” says Balster—either unintentionally or intentionally put underground—affect soil in some way. “I joke and say that we see the toupee. We see all the grass and landscaping, but a lot of what’s underneath could be highly variable and unknown.” Waste, fertilizer, asphalt, and even electrical infrastructure will all affect soil composition in different ways. Since inputs are so localized, urban soils can be incredibly heterogeneous. “Yeah, they’re fraught with challenges,” concludes Balster. “But that makes them fun and interesting to work with.”

Maintaining soil health, even in an urban space, is imperative to keep the surrounding ecosystem functioning and providing direct and indirect benefits to us all (ecosystem services like flood control, cultural services, and pollinator habitats). This is a key point that Balster wants his students to learn from this class.

“If I had to nail [the capstone class] down to one takeaway, mine would be that soils are foundational to the aesthetics and functionality of environments. And that if you don't know the media you're dealing with, the aesthetics and the functionality are compromised,” says Balster. “And you're going to pay for it, either in terms of the landscape not doing what you wanted it to do—flooding is an easy example—or aesthetically.”

A lawn of stone and steel

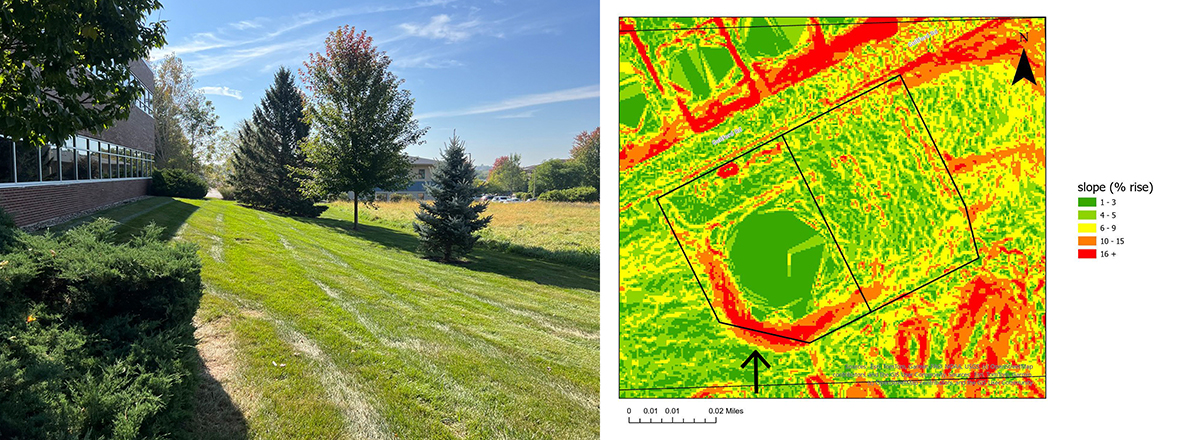

Before the students had the chance to assess the property, Balster guessed that water management would be the site’s biggest challenge. One of the defining features of the landscape is a large parking lot that’s about double the size it needs to be. On top of the asphalt, a substantial amount of water pools—which could be more than just a nuisance, as excessive runoff carries pollutants into the environment and can even overwhelm local drainage systems. Preventing runoff was one of the key problems the students aimed to address with green infrastructure.

In the field

The capstone class spent many of their fall afternoons at the ASA, CSSA, and SSSA headquarters, measuring soil organic matter, moisture, pH, and more. They asked fundamental questions about the soil physical and chemical properties and pointed out potential “problem” areas of the building that could be addressed with green infrastructure.

“We're out there trudging,” describes Luke Sprecker, an environmental science major in Balster’s class. “It's just all muddy and gross. [You’ve] got soil all over your hands, under your nails, it’s just everywhere. I mean like, that's part of the field experience, and it's fun.”

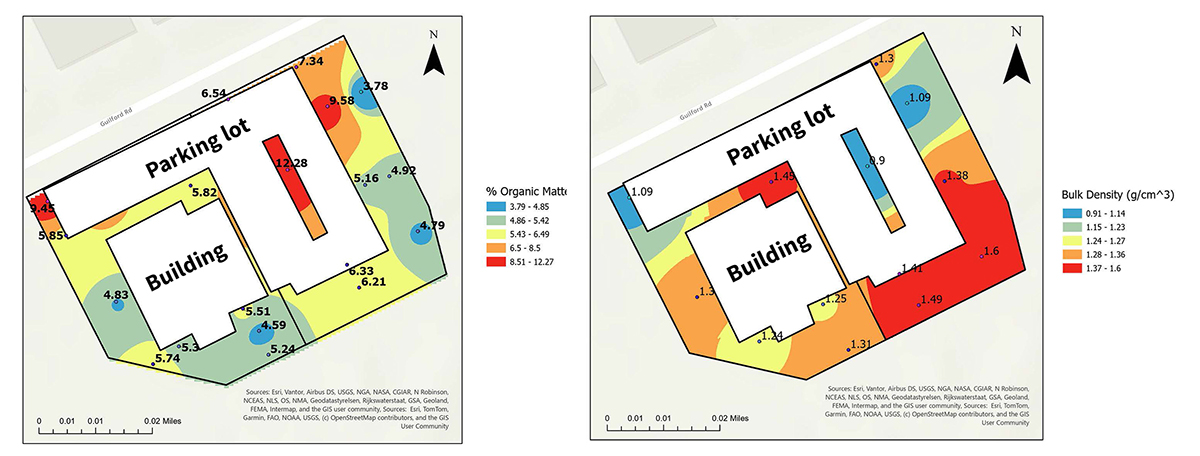

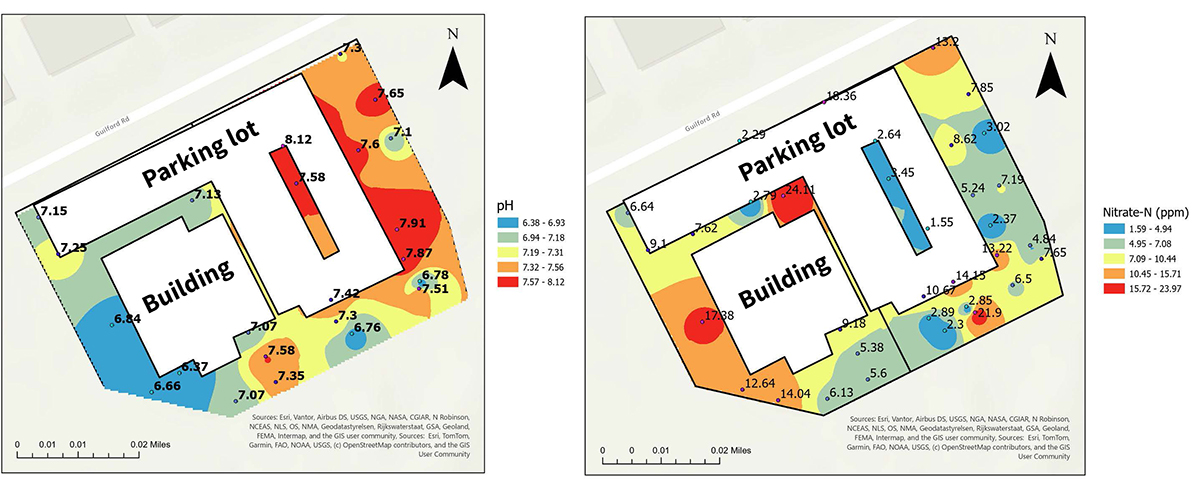

Sprecker explains that, over the course of a few weeks, the students assessed soil organic matter, infiltration (which he describes as assessing “where water flows in the ground quickest”), bulk density (which relates to how compacted the soil is), texture, pH, and salinity, along with site topography. The students also shipped soil samples to the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene (WSLH) for nutrient analysis (nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium). These soil analyses were aimed at understanding the key physical and chemical soil properties to inform potential green infrastructure implementation.

“The whole point of all these measurements is to get characteristics of the site, so we can determine, ‘OK, what actually can grow here, what can be successful?’” says Owen Weisse, another environmental science major in Dr. Balster’s capstone class.

Mapping the data

Soil properties varied greatly based on where samples were taken. To better characterize their findings, the capstone class collaborated with graduate students in UW-Madison’s Environmental Observation and Informatics (EOI) program.

“We're piggybacking off the soil sciences capstone class,” says Arik Waldinger, master’s student in the EOI program. “They're going out and taking soil samples around the sites, and it's our job to assist them by [getting] measurements of where those were taken to help with their analysis in the future.”

The graduate students use geographic information systems (GIS), a technology that attaches data to specific geographic locations. The maps (some of which are included in this article) will later be uploaded to a larger, publicly available StoryMap, which will tell an interactive narrative about the data collected by the two classes, the site design, and overall project goals. This StoryMap will be linked to another article in a future issue of CSA News.

The results

By combining lab results with the mapping done by the EOI cohort, the capstone class obtained a few snapshots of what’s happening underground. They presented their preliminary findings in a public presentation hosted by the university’s Department of Soil and Environmental Sciences. While the site was highly variable, there were key takeaways.

Preliminary analysis showed that there was an inverse relationship between bulk density and organic matter that held across the site: When soil organic matter increases, it gets less compact. That’s expected and is a good indicator of where plants could have a good opportunity to grow. Compaction can be detrimental to soil’s ecosystem services: It reduces water infiltration rates, increases runoff and flooding, weakens plant roots, and is even linked to higher amounts of pollutants in runoff.

Most areas sampled had positive and negative traits for supporting green infrastructure. For example, the students found that while organic matter was high in a small green space near the office parking lot (indicating that that spot would be a good area for plants to grow), the soil in that area had a slightly higher pH (a possible deterrent for many plants). This led the students to research localized solutions for each section of the site.

The solutions

At the end of their presentation, the students suggested several types of green infrastructure tailored to different parts of the site.

“If you look up green infrastructure online, you're going to find 50 different definitions,” explains Weisse. “The way I think about it is that you have some sort of urban landscape, and you're incorporating natural elements that mimic native processes. So, let's think of water retention, or water runoff: If you have just an asphalt parking lot, the water is just going to run right off. But if you have a pervious (permeable) parking lot where water seeps through, you can mimic the water retention practices on a native site. So, it's incorporating both an urban and a native element into something that works for both.”

While their suggestions are not official design proposals, they will be taken into consideration by the landscape architecture team in spring 2026.

Pervious pavements were suggested by the class to improve the functionality of the site. If in the budget, the current asphalt parking lot could be scaled down and swapped out with permeable material. This would filter water on-site and reduce pooling/runoff.

In addition, the students suggested planting a rain garden at the back of the building. A lot of water pools behind the building, partly because that’s where stormwater runoff is directed to drain off the roof, and partly because all that water collects at the base of a large slope behind the building. Water runoff from roofs often collects pollutants, so the water that collects at the base of the slope sits there, contaminated and untreated.

The students suggested planting a rain garden at the base of the slope using a diverse mix of plants native to southern Wisconsin. Rain gardens filter pollutants from stormwater runoff and provide shelter for pollinators and other beneficial wildlife.

Working with nature

But Balster reminds us that most forms of green infrastructure come with a condition: They aren’t “set it and forget it” solutions; you’ve got to put in the work of maintenance—and they all come with some form of maintenance. Rain gardens may require the most intensive care.

“I've done research on rain gardens. Homeowners who haven't had them before tend to want them as part of their landscape,” says Balster. “They love the sound of it. They'll typically put in a rain garden and plant it with a diverse mix of native, often flowering plants. Looks beautiful as they begin to grow. But, what we have found is that after about three to four years, as the gardens mature, they tend toward becoming a monoculture. Certain plants start to dominate over others, and it starts to become this uniform mix of plants.”

Monocultures are undesirable not only because they aren’t as eye-catching as diverse groups of plants, but also because the reduction in biodiversity can further reduce possible wildlife habitats and strain the soil’s resources over time. That doesn’t mean that rain gardens don’t work though. They just require a little bit of effort, like weeding, mulching, and even some thinning and replanting. That helps ensure the ecosystem services they provide, argues Balster.

“It's a garden, which means you've got to get in there and interact with it. You've got to work with nature. You've got to be part of the system,” says Balster. “I think that's one of the benefits of green infrastructure. There's a human, psychological, emotional benefit to being in nature. … Interacting with the complexity of pollinators, water, and the physical and chemical features—all those features that are built into that soil system of which we depend. That's a wonderful thing, in my opinion.”

You need to engage with green infrastructures because everything in your ecosystem—even the soil—is alive.

Little efforts go a long way

In the grand scheme of things, the Societies’ headquarters is a relatively small location. But even little changes can have bigger impacts than you’d think.

“A lot of times, the climate crisis and all this can seem super daunting,” says Weisse. “But if you see examples of smaller-scale projects—rain gardens or native plants—little things do add up, especially when it comes to a local ecosystem.”

Balster adds that it could also help educate the local community.

“That's going to catch people's eyes and they’ll go, ‘Well, why are you doing that?’ … And [you] could say, ‘We don't have any runoff on this site. All our water gets treated on site. And it's not through a treatment plant: It's through the soil system.’ Well, you know, a couple of minds are changed, that's success to me.”

What’s next?

While the capstone class’s work is done, the project is far from over. Stay tuned for updates as the graduate students’ StoryMap is published and the final landscape is designed and executed.

Most members of the capstone class are graduating this spring. They’re taking what they’ve learned from this course into the next stage of their career.

“I have really enjoyed having a class project that's ‘real’ and not just something that you have this made-up scenario for. It's really cool to have real-world implications for the work that you're doing,” adds Weisse, who hopes to go into science policy after graduating.

“For me, I think the thing I've gotten the most out of this class is being challenged,” says Sprecker, who did not have as much background soil science knowledge as some of his peers. “I've had to step up, do a lot of research on my own, look at articles related to soil science, and get caught up. I wanted to understand soil science because it'll be important for my future as I hope to eventually be working for the government or the state as a water management resource person. That's the end goal for me, and this class is getting me there by helping me understand more about what I need to know about soils for water management.”

The effects of the capstone course will still be seen years from now, in both the dynamic landscape and the lessons students take away. “It's a project that I hope will live beyond this class experience,” concludes Balster.

Acknowledgements

The Soils and Environmental Science (SES) capstone class is taught every year by Dr. Nick Balster, professor of Soil Science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The 2025 students include: Owen Weisse, Luke Sprecker, Megan Zlimen, Haley Bondoc, Lexie Hedrick, Cammy Whitcomb, Boya Shi, Caitlyn Garb, and Yier Fan.

Environmental Observation and Informatics (EOI) master’s students Mary Amponsah, Ava Beyers, Chenchen Ding, Matteo Franke, Ishmael Jalloh, Brittany Juneau, Connor Kasper, Michal Laszkiewicz, Annelies Quinton, and Arik Waldinger are mentored by Dr. Edward Boswell, teaching faculty at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Landscape architect Dr. Janet Silbernagel (Silvernail Studio for Geodesign) is guiding senior intern Jayita Burman on how to design a sustainable landscape for the Societies.

The ACSESS Sustainability Committee, led by Rebecca Funck, Susan Chapman, and Keith Lovejoy, coordinated this ongoing project.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.