Approaching Effective Mentorship Both as a Mentor and Mentee

Mentoring is a hands‐on form of career development. Effectively using mentoring as a career growth tool can lead to important outcomes such as degree completion (Lovitts, 2008), increased self‐efficacy (Paglis & Bauer, 2006), satisfaction with educational experiences (Gardner, 2009), and retention of students and faculty, especially for those who may be underrepresented or marginalized (Zambrana et al., 2015; Kricorian et al., 2020; Grunwald & Daroub, 2023), just to name a few.

Throughout our professional careers, we serve in positions of both mentor and mentee—providing as well as seeking support for a range of topics from career (e.g., sponsorship, coaching, and protection) to psychosocial development (e.g., support, role modeling, and counseling) (Johnson & Huwe, 2003).

As members of ASA, CSSA, and SSSA, it is in the best interest of our scientific community to shape mentor–mentee relationships effectively and to see that all individuals feel they are supported in achieving goals and advancing the field (Vaughan et al., 2019). Through our shared experiences, we offer insights on how to navigate mentor–mentee relationships. Based on our experiences as students and early career faculty, we focus on strategies that faculty or others in team leadership positions, postdocs, and graduate students can use, which include but are not limited to (1) assessing your needs, (2) maintaining effective communication, and (3) aligning expectations.

1. Assessing Your Needs

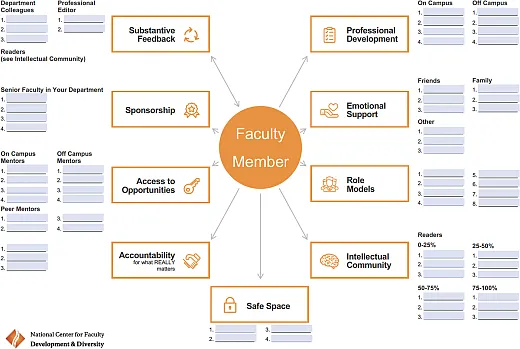

Self‐assessing your needs as a professional is the first step towards cultivating strong and authentic mentoring relationships. Figure 1 offers a great visual to “map” your mentoring network, identify your unmet needs, and plan how to expand your existing network. You may want to consult https://www.facultydiversity.org/ncfddmentormap for additional instructions on how to fill out this mentor map. Although initially designed for faculty members, the map can be easily adapted to your current needs, depending on your goals and where you are in your career path as a faculty member, graduate student, or postdoctoral fellow.

Advice for Faculty, Team Leads, or Mentors

Self‐assessing needs is critical both for mentors and mentees. We recognize that no one will do this deep reflection for us. It is contingent upon ourselves to discover what we need and when as needs are surely to evolve throughout stages of a graduate program or career. An unfortunate reality is that many of us are overcommitted without the capacity to consider what others need and perhaps not even what we need ourselves. Encouraging mentees to reflect on and communicate their needs is a valuable step. Relatedly, if mentorship truly matters to you, prioritize it! Make a conscious effort to prioritize who you want to be as a mentor from the beginning of a position.

Advice for Postdocs, Graduate Students, or Mentees

Your adviser can be a key mentor, but as the mentor map indicates, it is wise to cultivate a variety of mentors, which may include other faculty, peers, university administrators, and professional societies (Barnes et al., 2021).

You might ask yourself questions such as “What are the skills I hope to gain in this role/project?” “What are my strengths and weaknesses in areas such as problem‐solving aptitude, time and budget management, independent thought process, manuscript and grant writing, data analysis, and leadership skills for which I may require mentorship?” And “What are my current needs and life/career goals?” Reflecting on these questions is important—you should not expect that someone will be ready to anticipate all of your needs and hopes. Being successful requires at times deep reflection!

Professional associations, at local, national, and international levels, are also a great opportunity to broaden and expand the scope of potential mentors that could meet your needs and goals. For example, the Graduate Student Networking Session and other programming available at the ASA, CSSA, and SSSA Annual Meeting can help you engage with professionals as well as establish meaningful career/lifelong connections.

2. Maintaining Effective Communication

Similar to teaching, mentoring involves the exchange of information and experiences between people. Learning how to communicate with each other can increase the likelihood that both mentors and mentees are open to sharing ideas, accomplishments, and challenges they are experiencing. Additionally, mentors and their mentees may or may not come from similar walks of life, so learning how to communicate and establish a relationship across differences is important to ensure equitable access to the beneficial outcomes of mentoring.

Advice for Faculty, Team Leads or Mentors

It can pay dividends to consider and design systems for communication with mentees. This might include intentionality around the frequency of meetings, a process for how meetings will proceed, and more. While some communication might happen organically, intentionally designing space and time for communication benefits both mentor and mentee. In particular, it allows space for building trust in order to navigate conflict or more challenging periods.

Advice for Postdocs, Graduate Students, or Mentees

Be specific and clear on your asks—feedback on your writing, advice on how to handle a conflict, suggestions for course or professional development opportunities, requests of a recommendation letter, vacation leave, conference attendance, or any other needs. The more specific you are, the more you benefit from the support your mentor can provide.

Make mentor–mentee meetings matter. This is particularly crucial to interactions with advisers and reflections on how to turn meetings from status updates to remarkable and meaningful conversations. It is important that you take ownership of every meeting attended, reflecting on your role in the conversation as well as post‐meeting action items. Here are some strategies that have worked well for us:

- sharing a suggested meeting agenda, either prior to or right before the meeting, shows that you are a serious, organized, and productive scholar who is committed and respectful for each other’s time;

- taking notes during the meeting and archiving meeting minutes in a sharable doc as well as a follow‐up email or message with the main points discussed can also help summarize the key points of the conversation; and

- sharing records and tracking of project/program progress through weekly updates (via email or shared Google Docs) or web‐based platforms such as Trello can help to keep everyone on the same page.

Seek opportunities to improve your communication skills. Mentoring undergraduate students and visiting scholars in your team, either formally or informally, can be an effective way to assess and learn how to approach best practices in communication as well as understand the situation through both mentor (now you!) and mentee (student support) lenses.

3. Aligning Expectations

One aspect of mentoring involves empowering mentees to unleash their potential—inside and beyond academic settings. Building on the other suggestions, dedicated time to discuss and align clear goals and expectations from everything large (i.e., timing for graduation, post‐graduation goals, and thesis or dissertation chapter deadlines) and small (i.e., professional development experiences sought) in a program or role can be helpful for anchoring those relationships. We feel this is related to but distinct from both assessing needs and effective communication.

Advice for Faculty, Team Leads or Mentors

A few questions to consider might include: What systems are in place (i.e., regular check‐in meetings or conference presentations) to check in on expectations and progress? Are you communicating clearly about expectations from the start of a position or program with your mentees? If not, what might be adjusted?

Advice for Postdocs, Graduate Students, or Mentees

Understand that you are not alone. While seeking support from a mentor, remember that they are also human beings with their own needs and goals (and who are most likely navigating other mentees’ needs and requests). Thus, to navigate those relationships, it’s important to be reasonable in your requests and reflect on questions such as, “Is this an appropriate time window to work with?” And “Is my request aligned with individual skills and capacity?”

Suggest an individual development plan (IDP) to discuss with your mentor short‐ and long‐term goals and activities to reach those goals. Some universities and programs provide specific IDP templates that mentors and their mentees could use while online tools like MyIDP (https://myidp.sciencecareers.org) are also available. Including the scope and limitations of your projects as part of your IDP can also help identify what realistically can be accomplished in your program as well as possible new projects and extracurricular opportunities to fill your skills gaps.

Understand that the real life/career journey is a bumpy road. Challenges such as a rejected paper, changes in suitable days for fieldwork, or anticipated/delayed graduation plans affecting post‐graduation job opportunities require us to reassess our plans periodically. At this point, it’s incredibly important to pause and assess your progress. This is an opportunity for you to evaluate the effectiveness of your work/life habits (writing, data collection, class attendance, care for your physical and mental health, and so on). Whenever reassessing your plans, using SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time‐Bound) can help effectively discuss and align mentor–mentee expectations regarding your project/degree/program goals.

4. Effective Mentoring Practices—If Not Now, When?

The need not only for more agricultural professionals in general, but particularly for those underrepresented or marginalized in the past should lead us as a community to recommit efforts, with increased urgency, to how we assess, value, and implement effective mentoring practices (APLU, 2022). As we reflect on what mentorship has done for us at each turning point in our careers, there is much to be thankful for. We hope the thoughts and resources shared here help you to move from a reactive to a proactive stance—where you feel empowered to initiate contact, ask for what you need, and focus the interactions on what matters. Moving forward in this way will help you feel more connected to instrumental people in your department and institution, open networks of opportunities, and solidify your professional relationships.

References and Additional Resources

American Psychological Association. (2006) Introduction to mentoring: A guide for mentors and mentees. https://www.apa.org/education‐career/grad/mentoring

APLU. (2022) Advancing equity, centering student perspectives. Association of Public & Land‐Grant Universities. https://www.aplu.org/wp‐content/uploads/advancing‐equity‐centering‐student‐perspectives.pdf

Barnes, L., Grajales, J., Velasquez Baez, J., Hidalgo, D., & Padilla‐Benavides, T. (2021) Impact of professional and scientific societies’ student chapters on the development of underrepresented undergraduate students. Frontiers in Education, 6, 763908.

Gardner, S.K. (2009) Contrasting the socialization experiences of doctoral students in high and low completion departments. The Journal of Higher Education, 81(1), 61–81.

Grunwald, S., & Daroub, S. (2023) A 360° perspective of women in soil science focused on the US. Frontiers in Soil Science, 3, 1072758.

Johnson, W.B., & Huwe, J.M. (2003) Getting mentored in graduate school (1st edition). American Psychological Association.

Kricorian, K., Seu, M., Lopez, D., Ureta, E., & Equils, O. (2020) Factors influencing participation of underrepresented students in STEM fields: matched mentors and mindsets. International Journal of STEM Education, 7, 1–9.

Lovitts, B.E. (2008) The transition to independent research: Who makes it, who doesn’t, and why. Journal of Higher Education, 79(3), 296–325.

Paglis, L.L., Green S. G., & Bauer, T. N. (2006) Does adviser mentoring add value? A longitudinal study of mentoring and doctoral student outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 47(4), 451–76.

Taskey, R.D. (Ed.). (2020) The Graduate Student’s Backpack: It’s what You Need on the Research Path. ASA, CSSA, and SSSA. https://acsess.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.2134/2012.graduate‐students‐backpack

Vaughan, K., Van Miegroet, H., Pennino, A., Pressler, Y., Duball, C., Brevik, E. C., … & Olson, C. (2019) Women in soil science: Growing participation, emerging gaps, and the opportunities for advancement in the USA. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 83(5), 1278–1289.

Zambrana, R.E., Ray, R., Espino, M.M., Castro, C., Douthirt Cohen, B., & Eliason, J. (20151) “Don’t leave us behind”: The importance of mentoring for underrepresented minority faculty. American Educational Research Journal, 52(1), 40–72.

CONNECT WITH US!

If you would like to give us feedback on our work or want to volunteer to join the ACS Graduate Student Committee to help plan any of our activities, please reach out to Maria Teresa (mariateresa.tancredi@uga.edu), the 2023 chair of the committee!

If you would like to stay up to date with our committee, learn more about our work, contribute to one of our CSA News magazine articles or suggest activities you would like us to promote, watch your emails, connect with us on Twitter (@ACSGradStudents) and Facebook (ACS.gradstudents), or visit: agronomy.org/membership/committees/view/ACS238/members, crops.org/membership/committees/view/ACS238/members, or soils.org/membership/committees/view/ACS238/members.

If you are attending the 2023 ASA, CSSA, and SSSA (ACS) Annual Meeting in St. Louis, don’t forget to check out the workshop, tour, and special sessions organized by our ACS Graduate Student Committee and come meet us at our in‐person meeting—look for the Graduate Student Committee Meeting on the agenda!

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.