Advocating for Continued Federal Support of Agricultural Research, Teaching, and Extension

Around 50 members of ASA, CSSA, and SSSA, including several Certified Crop Advisers (CCAs), recently converged in Washington, DC for our in-person Congressional Visits Day. It was an exhilarating and exhausting experience, requiring high stamina getting from one set of capital buildings (house to senate) and then back to meet congressional representatives in both chambers. The primary goals of this (literal) exercise were for our congressional representatives to understand why continued and increased funding is needed for agricultural research, to put a human face on some agricultural science constituents, and to elevate our scientific Societies and their members, the later being part of our strategic plan.

What happens at Congressional Visits Day? Before Congressional Visits Day, we first attended a well-planned training day organized by ASA, CSSA, and SSSA staff. There we learned about effective strategies and were also cautioned that the cynicism and political drama seen on television and social media have no role in our activities or in our advocacy. Congressional offices seek to support and please their constituents, so our messages about the need for enhanced agricultural research funding is one every elected office can get behind. On the actual Congressional Visits Day, teams of two to four of us broke up by groups of states. We were scheduled for numerous 30-minute meetings with our representatives’ offices. These meetings are generally with staff from the Congress member’s team, ideally senior staff and those with agriculture in the portfolio of topics they handle. Everyone quickly introduces themselves, and we pitch our “asks.”

Thankfully, the awesome ASA, CSSA, and SSSA staff set up everything regarding our visits and helped coordinate each team requesting the same things using a similar messaging, complete with beautiful one-page, state-specific handouts. During these meetings, we also discover how to formally submit such “appropriations” requests and share with congressional staff that they will have broad and bipartisan agreement on our specific asks. This is important every year, but especially in years like this one, following a period of record federal growth in spending. Some congressional offices communicated that there was little appetite for increasing budgets of federal agencies.

Is Advocacy a Good Use of Member Resources?

Is this activity a good use of member resources? When I worked at the USDA Office of the Chief Scientist in DC, I saw first-hand that stakeholder visits like these elevate the visibility of any issue and keep it part of the discussion. There are so many different issues of importance happening in the U.S., so our action is needed to attract congressional attention to topics we care about. If we are not proactively at the table and bringing awareness to our work with Congress, we cannot expect federal resources and opportunities to support our needs.

[By] being a member, publishing in our journals, and attending the Annual Meeting, you are indirectly supporting the advocacy for resources and policies that benefit your discipline at the highest levels of government.

On the day we were in DC, we informally ran into stakeholders from groups representing museums, autism care givers, and veterans of foreign wars, among others; these were citizen constituents, not lobbyists, each advocating for their own appropriations or legislation. Putting on a great showing, as we did, requires financial support that many groups cannot raise. The congressional visit activities of ASA, CSSA, and SSSA are actively supported by your membership, publications, Annual Meeting attendance and by returns on an investment portfolio from current and past members. The budget supports not only staff and leadership’s coordinated visit, but also early career and graduate student members. In other words, by being a member, publishing in our journals, and attending the Annual Meeting, you are indirectly supporting the advocacy for resources and policies that benefit your discipline at the highest levels of government.

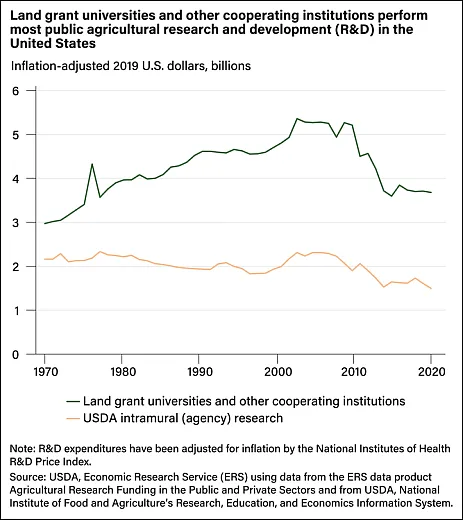

with inflation. Source: USDA Economic Research Service.

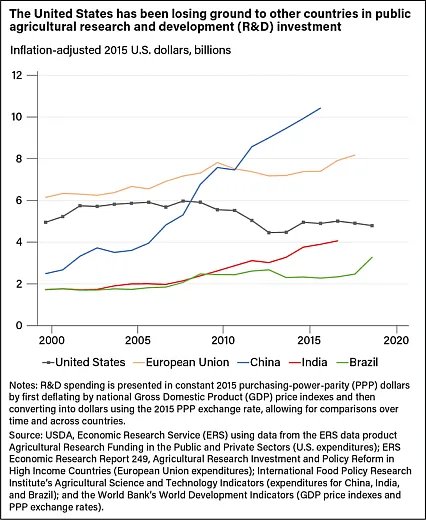

This advocacy is a common good, it is big and complex, which arguably makes it often difficult to point to individual “wins” that directly result from advocacy like Congressional Visits Day. However, public funding for agriculture research has not kept up with inflation (Figure 1), despite an impressive $20 in benefits to the U.S. economy for every $1 of spending (Nelson & Fuglie, 2022). I would suggest we need more engagement, not less, to communicate the returns on agricultural research. This is why activities like a virtual Congressional Visits Day, which can include more members to participate at a lower cost, are innovative forms of advocacy we hope you will engage in.

Whether in-person or virtual, there are ancillary benefits to CSSA supporting Congressional Visits Day. One important benefit is the training, networking, and comradery that is built, especially among our early career members as well as board members. Going through this rigorous exercise requires attendees to practice elevator speeches and justify the benefit of public dollars supporting our work, helping to put our research in perspective. Since few congressional offices have backgrounds or expertise in agricultural science or even agriculture, this must be at a lower comprehension level than usual scientist-to-scientist elevator speeches. I really enjoyed seeing graduate students and early career members thrive in action; they do an amazing job, and our future is very bright. I tried to convince my early career teammates (Dr. Brinkley and Ms. Rastogi) that they should be the ones running for Congress (Figure 2) or at least explore science policy as a future career! If any of our many members chooses a science policy career based on their congressional visit experiences (like Dr. Rachel Owen!), it would be a win for the crop sciences.

What Did We Ask For?

What “asks” were made? Its worth communicating asks made on the Societies behalf briefly, but I would be happy to go into the process and more detail another time. The first two of these asks were for increased appropriations on competitive grants: (i) an increase of $45 million for USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Agriculture and Food Research Initiative (USDA-NIFA-AFRI) to $500 million and (ii) to fully appropriate the Agriculture Advanced Research and Development Authority (AgARDA), which is a program authorized in the 2018 farm bill. While authorization allows Congress to appropriate a ceiling amount of money (AFRI = $750 million; AgARDA = $50 million), appropriations are the actual money budgeted (currently AFRI = $455 million; AgARDA = $1 million).

ah Brinkley and Khushboo Rastogi.

Another of our asks for the upcoming farm bill is the continued appropriations of Foundation for Food and Agricultural Research (FFAR), a competitive grants program that is separate but complementary to AFRI. You might notice a trend here that most of our advocacy was for additional funds for competitive grants and wonder what makes competitive grants rise to the top of the list.

Competitive funding is seen as politically achievable for a number of reasons. It can be painted as benefitting all stakeholders and constituents in the U.S. who can compete for it. One of the handouts we shared with congressional staff showed how much of the competitive AFRI money was brought to the state they represent. In contrast, capacity or formula funds are non-competitive funding appropriated by Congress directly to specific groups; this type of funding does not currently receive the same buy-in of advocacy. For instance, USDA-HATCH capacity funds benefit only land grant universities and are sometimes painted as having lower accountability by groups ineligible to receive these funds and who want this converted into (competitive) funds that they can receive.

The USDA Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS), Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS; Figures 1 and 3), and National Agricultural Statistics Service (USDA-NASS) are also non-competitive appropriations that play critical roles in our agricultural research ecosystem, and we need to help maintain them. However, federal employees are discouraged and/or barred from advocacy work, so these agencies receive less visible advocacy to Congress. Capacity funds are critical to maintain positions and capacity in areas of importance, especially those that need long term funding. My predecessor’s predecessor in my maize-breeding position had multiple technicians and a secretary supported by capacity funds; now every program employee must be externally supported by competitive grants in my program. From a recent study, this appears to be common scenario for many plant breeders (Coe et al., 2020) despite the fact that the timeline to develop a new cultivar (more than seven years) exceeds that of a competitive grant (three to five years).

Source: USDA Economic Research Service.

Does the Competitive Grants System Make Sense?

Does the competitive grants system make sense? From an academic land grant institution standpoint, where faculty are increasingly required to support research and training with competitive grants, the answer is likely no in practice at the current rate of funding (which is why we are advocating for more); but yes politically as explained above. For example, one of the recent AFRI programs reported a 5% funding rate. That means, all things equal, a person must write 20 grants to have one funded. I budget about 120 hours to write each federally competitive grant, which is 2,400 hours of grant writing. There are 2,080 hours in a work year, meaning we could argue more than a year of full-time work is needed to be successful on one grant. A $500,000 AFRI grant generally only supports one five-year Ph.D. student and some research activities, as strange as this may sound to someone who has not administered one. This grant writing time takes us away from our land grant mission of doing the research, teaching, and service. Furthermore, serving on the review panel can easily take 100 hours to review submissions, and if we’re submitting 20 grants, we should probably serve on three review panels per year.

With current funding levels, less than one-third of AFRI grants recommended for funding are able to be funded. From my personal review panel experiences, I think about 70% of all submitted grants deserve funding. With current funding levels, the U.S. competitive grants system does not make much sense to best advance the agricultural research mission. So either substantially more funding is needed (advocacy) or a return to capacity funds are needed; the later does not seem culturally or politically feasible. I look forward to hearing from you regarding your thoughts on this.

Overall, we each need continued federal support of agricultural research, teaching, and extension for our discipline to make gains in addressing future challenges, training the next generation, and providing unbiased information to growers. Internationally, U.S. public investments are falling behind (Figure 3). Improving this situation requires advocacy by all of us for all components of the land grant mission. I hope you will considder participating in Congressional Visits Day in the future and reach out to your congressional representatives to tell them that agricultural research is important, both in competitive and capacity science.

References

Coe, M.T., Evans, K.M., Gasic, K., & Main, D. (2020). Plant breeding capacity in US public institutions. Crop Science, 60(5), 2373–2385.

Nelson, K.P., & Fuglie, K. (2022, 6 June). Investment in U.S. public agricultural research and development has fallen by a third over past two decades, lags major trade competitors. Amber Waves. USDA Economic Research Service. http://bit.ly/3KfRLgA

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.