Today’s challenges to food security for smallholder farmers

On steep slopes in developing countries like Nepal and Ecuador, smallholder farmers rely heavily on agriculture for their livelihoods.

Increasing erosion, decreasing rainfall, and climbing global temperatures threaten near-term food security; conservation agriculture can help.

A new special issue of Agronomy Journal gathered insights from around the world, highlighting the role of conservation agriculture in combatting today’s food security threats.

Both Nepal and Ecuador have one thing in common: incredible mountains. Well, two things: incredible mountains and a high-stakes struggle with soil erosion and climate change that’s negatively impacting smallholder farmers.

Though they’re more than 10,000 miles apart, conservation agriculture can solve some of the parallel challenges these countries face. In Ecuador, farmers are battling soil erosion that hugely outpaces soil formation. In Nepal, they’re struggling with erosion, too; along with steadily rising temperatures and declining rainfall.

These two regions show the lessons we can learn from smallholder farmers in vastly different areas of the world, and how conservation agriculture can help them improve their livelihoods and conserve our most valuable resource of all: the soil.

Here, guest editors of the Agronomy Journal special section, “Near-Term Problems in Meeting World Food Demands at Regional Levels,” describe the impetus for collating these important papers (https://doi.org/10.1002/agj2.20930). Beyond Ecuador and Nepal, the special section includes 16 other papers highlighting challenges to food security around the world, including submissions from Africa, Asia, and South and North America. The papers address pest and water management issues, the need for precision agriculture and workforce development, and the threats posed by herbicide-resistant weeds and changes in climate. They also span crops, from the rotation of perennial grass with annual crops in Africa to the production of rice and shrimp in China. Taken together, this selection of papers presents the state of global challenges to food security.

In this article, we’ll take a deep look into the parallels in problems faced by smallholder farmers in the mountainous regions of Ecuador and Nepal. We’ll hear from the researchers who study these problems, from cataloguing soil loss in the Andes to documenting rising temperatures in the Himalayas.

Today’s Issues, Not 2050’s

It’s not every day that you get both of your guest editors in range of a single webcam. Sharon Clay and Thandiwe Nleya sat in Nleya’s office in the Agronomy, Horticulture, and Plant Science building at South Dakota State University where Clay is a distinguished professor of weed science and Nleya is an associate professor of agronomy.

So where did they get the idea to gather a global cross-section of papers on near-term challenges to food security?

“Oh, Thandi [Nleya] told me she wanted to look at these problems, and I told her she should definitely put together a special section in Agronomy Journal,” Clay, a past president of ASA, remembers. “We just knew: everybody is thinking about the long term—what’s going to happen in 2050? But we thought, what’s going on right now? What are the near-term issues we can address that will get us down the road to solving these problems by 2050?”

Agriculture is the economic backbone of developing countries. Even though 75% of the population in the world’s least-developed countries live in rural areas, nearly 1 in 10 are severely affected by food insecurity. Conservation agriculture—which includes reducing tillage, increasing the amount of time the soil is kept covered by leaving residue and planting cover crops, and diversifying the species in rotation—is one way to protect the agricultural resources that both feed and provide income to rural residents of developing countries.

“We’re all facing the same challenges due to climate change,” Nleya says. “But in these resource-poor countries, even small changes to their agricultural practices can mean better food security.”

So Nleya and Clay invited researchers from around the globe to submit their perspective on the near-term challenges that are threatening food security, as well as the conservation agriculture solutions that could help them.

The Ecuadorian Andes

In the Ecuadorian Andean region, a team of researchers estimated that soils are sloughing off of fields at a rate that exceeds soil formation by up to 300 times. Some farms have erosion so severe, the shining white parent material peeks through the topsoil. In other places, farmers have abandoned their unproductive fields entirely.

“It’s a complex situation that doesn’t just affect smallholder farmers in the region,” Jorge Delgado says. Soils from the high-mountain regions ends up in waterways, increasing the chances of flood and decreasing water quality for those in lower-lying regions. “We’re studying how conservation agriculture can help slow down this unsustainable soil erosion.”

Delgado, along with Jeffrey Alwang and first author Victor Barrera, draw on nearly a decade’s worth of the team’s research in Ecuador with the article, “Conservation Agriculture Can Help the South American Andean Region Achieve Food Security” (https://doi.org/10.1002/agj2.20879).

But if you really want to figure out how Delgado, a soil scientist in Soil Management and Sugarbeet Research at a USDA-ARS office in Colorado, ended up working with smallholder farmers in Ecuador, turn your eyes toward Jeffrey Alwang.

Alwang is a professor of agricultural economics at Virginia Tech. Back in 2005, he was already a decade into an integrated pest management project in Ecuador when he needed to find an expert in soil erosion for a new grant he was working on.

“I did a quick internet search and found Jorge [Delgado],” Alwang says. “I sent him an email…it must have been four in the morning for Jorge, and within five minutes, the phone rang.”

The two have worked together ever since. Their article co-author is their primary contact in Ecuador, Víctor H. Barrera, a researcher at the Institute Nacional de Investigaciones Agropecuarias (INIAP).

Their contribution to the Agronomy Journal special section relies on a bilingual nitrogen index tool that Delgado developed, calibrated, and validated. Additionally, he estimated the depth of surface soil lost due to these high erosion rates, comparing them to estimates of the depth of soil formation. Delgado found that farmers in the region suffer from a combination of agricultural practices that can exacerbate soil erosion. Steep slopes coupled with heavy rainfall and soil left bare results in a net rate of erosion that is unsustainable and—if left unaddressed—will become catastrophic for regional food security.

“We would go to farms and see some farmers cultivating down these 30% slopes,” Alwang remembers. “They couldn’t drive a tractor across the contour—it would tip over—so they’d swing around the edge of the field, cut across the top, and just plow straight down the slope.”

Other farmers—those who don’t rent tractors—might hoe the soil by hand, but even then, they’d hoe down the hill since it’s much easier than moving across it.

This intensive method of cultivation is a contributing factor to the team’s shocking estimate of soil erosion. They posit that erosion outpaces soil formation by as much as 286 times. That rate is completely unsustainable and could lead to the rapid loss of viable agricultural land in the region. With it? The landowner’s livelihoods.

Conservation agriculture is one solution that can help these farmers maintain their soil, which is their most valuable economic asset.

“For the first couple of years we were there, we spent a lot of time showing these farmers how to use contours, how to put in water-diversion ditches,” Alwang says. “We used live barriers of native trees or bushes on the edges of fields to slow soil erosion.”

Along with contour plowing and hoeing, the team also looked at the results of leaving crop residue on the field over the winter, managing nitrogen fertilizer use, and implementing no-till.

“Nitrogen management is very important and can significantly increase net economic returns for these smallholder farmers,” Delgado says.

In fact, they found that optimizing farmers’ nitrogen use boosted their net economic returns by 10%. In another study, published in Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment in 2019, the team discovered that nitrogen management improved net economic returns by up to 22% at another location in Ecuador (https://doi.org/10.2134/age2018.10.0050).

“Using these improved nitrogen management practices could potentially increase net economic returns for over 200,000 farmers in the region,” Delgado emphasizes.

The bigger benefit comes from a more diverse rotation, incorporating potato, oat, vetch, barley, faba bean, and pasture. This diversified rotation is more complex than the potato–pasture system that many households relied on, with pasture used to feed their livestock.

“The big increase in profit comes from the reduction of labor with a diversified rotation,” Alwang says. “If they’re using conservation agriculture, it’s a 10 to 15% decrease in labor since they’re spending less time preparing the land, less time hoeing, and less time weeding.”

The soil cover and diverse rotation has also shown some small increases in soil health over time.

“But really, we’ve picked up improvements in yield and reductions in cost,” Alwang says. “And that’s really what’s driving profitability for these farmers.”

That profitability can immeasurably impact lives.

The Path Forward in the Highlands

There was one farmer that Alwang met early on during his time in Ecuador that exemplifies the possibilities inherent in conservation agriculture practices. His name is Venicio Paguay.

“When we started working in Ecuador, we met this really young farmer. He had about 22 acres of land and six small kids,” Alwang says. “And his goal was to be able to produce enough, earn enough, that his children don’t have to do what he’s doing. He had the equivalent of a sixth-grade education, and he wanted [his kids] to have other options, to get an education.”

Over time, Paguay took every bit of advice that Alwang and his co-researchers offered. He dug diversion ditches to stop water running down his fields, slowing soil erosion. He put in a small pond to farm fish, adding an extra source of protein for his family. And he started growing heirloom potato varieties that he sells at a premium.

“He was a really enterprising guy,” Alwang says. “He’s still humble, he lives in a shack, but everything he’s made, he’s invested in those kids. The last time I saw him, back in 2015, his two oldest kids were getting university degrees.”

Venicio Paguay stands as a great example of the possibilities that these changes offer. Not only do they protect the watersheds in the area from the devastating effects of soil erosion, but they often improve the quality of life for the farmers themselves. Alwang and Delgado mentioned a final pressure point that’s keeping farmers from adopting conservation agriculture practices.

“There’s just not enough extension,” Alwang says. “Though every time we come back, we see more farmers contour plowing or leaving residue, it’s usually because they’ve seen their neighbors doing it.”

For wider-reaching impacts, dissemination of this information needs to be much broader—it will take collective effort, including state-run extension that increases adoption and diffusion of conservation agriculture practices.

“Results from our research demonstrate that we can use agronomy, crop science, and soil science to help us develop solutions to the challenges…which pose threats to both the food security and national security of countries throughout the world,” Delgado says. He emphasizes that his team’s results show how conservation agriculture and other key best management practices could be used to mitigate the effects of risky soil and cropping system combinations that adversely impact sustainability and all of the other problems that arise when the soil is severely eroded.

Nepal’s Changing Climate

Halfway across the world, another mountainous developing country is facing many of the same struggles as smallholder farmers in Ecuador.

In fact, Deepak Joshi—a researcher and doctoral candidate at South Dakota State University—collaborated with Sharon Clay and several researchers in Nepal to catalogue how climate change is impacting agriculture in Nepal.

“I was born in Nepal—I grew up in Nepal,” Joshi says. “When this special section came up, I knew I wanted to contribute to the literature on agriculture in Nepal because there is so little peer-reviewed information there in the agricultural sector.”

So Joshi, Clay, and their coauthors did so with their article, “Conservation Agriculture for Food Security and Climate Resilience in Nepal” (https://doi.org/10.1002/agj2.20830).

Like the farmers combating erosion in the Andes, farmers in Nepal are losing invaluable topsoil, too. A study in Soil Systems estimates that topsoil in Nepal is eroding at the unsustainable rate of 1.7 mm per year (https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems3010012). To understand how farmers can take on the one-two punch of soil erosion and a changing climate, you first have to understand their current cropping systems.

Farmers in the high mountain regions typically cultivate maize in rotation with either finger millet, buckwheat, or wheat/barley. Some simply grow buckwheat or potato followed by a fallow period. Like Ecuador, farmers often rely on livestock grazing in the rough, steeply sloped terrain, which they consume as protein or use for milk production.

But below that, there’s the “middle mountains,” where farmers grow terraced rice, winter legumes, maize, wheat, and vegetables. In the lowlands, they often cultivate rice in rotation with wheat, maize, or vegetables.

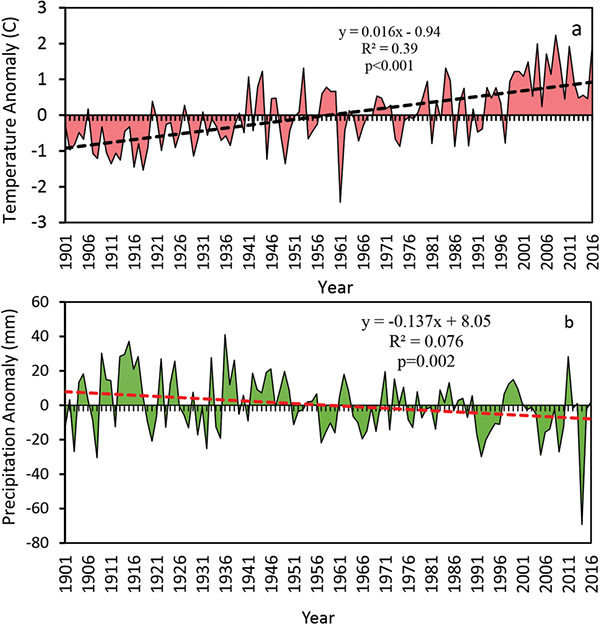

Armed with the major cropping systems in these three different ecological zones, the team dug into the challenges facing them. In fact, Joshi collected 116 years’ worth of data on precipitation and temperature in Nepal, collating it to calculate the overall trend. He found that temperature is rising while precipitation is falling.

“I knew it was happening, but I’d never seen it laid out like this,” Joshi says. The average temperature from 1977 to 2009 has been increasing by 0.06°C while precipitation since 1975 has been declining by 0.255 mm per year.

The warming climate exacerbates the food insecurity many farmers in Nepal already face. Low crop productivity plagues many while those in the middle and high mountain regions face soil erosion when cultivating. There’s a severe lack of training and extension to educate these farmers and improve their practices.

“The greatest challenge in Nepal is that you primarily have to rely on the limited flat lands for agriculture; most of the available land is really hilly, and it’s a very challenging landscape for production,” Joshi says. Farmers often have only an acre and a half to two acres of land on which to produce food, and the landscape itself limits the use of large equipment. “And farmers will do whatever their parents did, or their grandparents did. We definitely need some policies in place that will help provide farmers with better education and more sustainable technology.”

Joshi and his coauthors call for such policy in their study. They recommend more investment in research, outreach, and technology development for hilly regions with a focus on conservation agriculture technology. Their study cites all the benefits that come with conservation agriculture—the improved soil organic matter, reduced soil erosion, increased water use efficiency, and reduced greenhouse gas emission.

Joshi hopes that this study will inform the future of agriculture in Nepal, providing policymakers with the structure to make informed decisions and increase the country’s food security.

What’s Next?

A common thread through these two studies is the need for improved extension and education. It is possible for farmers to effectively implement conservation agriculture to protect their farms, their families, their livelihoods, and the land they manage—if they have the resources to do so.

“You need to get everybody on the same page—at the watershed level, regardless of political boundary lines—to make change,” Alwang says. “My hope is these farmers keep doing what they’re doing, and we’ll continue doing the work.”

And there’s an economic incentive to improve agriculture, too. For these labor-intensive systems, adding in well-planned cover crops can cut back on the labor needed for weeding or hoeing. Using no-till decreases labor costs, and improving extension gets the word out to farmers about new ways to farm that don’t lead to erosion, soil degradation, or yield losses.

“What’s most striking to me is, when we get these international papers together, the problems are very similar,” Nleya says. “We can collaborate to help people from other parts of the world where they’re struggling with resources, and the technologies we generate can be adapted to help those in other parts of the world, too.”

Conservation agriculture could be the tectonic shift in perspective that these smallholder farmers need to maintain their land, so many can continue passing it down for generations to come.

“The results of these studies really show how conservation practices are essential to protect soil and water resources around the world, which will be important for climate change adaptation and the food security of billions of people,” Delgado says. “The results of this research are crying out to all of us: ‘Take care of the soil or it will be destroyed; if you take care of the soil, it could help you adapt to a changing climate.’”

Dig deeper

The Agronomy Journal special section, “Near–Term Problems in Meeting World Food Demands at Regional Levels,” can be viewed at: https://bit.ly/3sZHGvw.

Specific papers of interest include:

- Introduction to the special section, “Near-Term Problems in Meeting World Food Demands at Regional Levels: A Special Issue Overview”: https://doi.org/10.1002/agj2.20930

- “Conservation Agriculture Can Help the South American Andean Region Achieve Food Security”: https://doi.org/10.1002/agj2.20879

- “Conservation Agriculture for Food Security and Climate Resilience in Nepal”: https://doi.org/10.1002/agj2.20830

- Delgado et al.’s 2019 paper in Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment, “Conservation Agriculture Increases Profits in an Andean Region of South America”: https://doi.org/10.2134/age2018.10.0050

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.