A new method for monitoring water dynamics in rock

Measuring soil moisture is commonplace, but measuring moisture in rock? Not so much.

Scientists at Texas A&M piloted a new method of measuring rock moisture using an inexpensive soil moisture sensor.

Here, their method details an inexpensive means of better understanding the dynamics of water movement in rock—and how that water content supports plant life in dry environments.

Over the last 150 years, the once-healthy prairies atop the Edwards Plateau in Texas have changed drastically. No longer rich with grass species after chronic overgrazing, the stony, thin layer of soil is becoming more and more exposed. Shrubs and trees—particularly juniper—are creeping onto these grasslands. In the process, they’re creating bare patches of earth where multiple species once thrived.

But the encroachment of woody species is shrouded in a bit of mystery: where are the trees and shrubs getting enough water to grow in such low-moisture environments?

They could be tapping into rock.

“In Texas, there’s this enormous limestone formation, the Edwards Plateau, which is 90 square miles of Karst geography,” says Bradford Wilcox. “In the last 150 years, it has converted from grassland to oak and juniper woodlands after a period of extensive overgrazing. And a question that we’ve had for some time is to what extent are trees getting water from the weathered rock and rock substrate?”

Wilcox is the Sid Kyle Endowed Professor in Semi-Arid Land Ecohydrology at Texas A&M. His advisee, Ph.D. candidate Pedro Leite, is first author of a new study in Vadose Zone Journal documenting a detailed method for installing soil moisture sensors in rock (https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20164). Their method provides the groundwork (if you’ll pardon the pun) for a new, reliable method of measuring a key part of the hydrological cycle: water retention in rock.

Rock Moisture

So who cares about rock moisture? Why, you should.

Rock moisture is key for contributing to groundwater recharge. At the Texas A&M field station near Sonora, TX, the Buda limestone formation undergirds their section of the Edwards Plateau.

“Regionally, the Edwards Plateau supplies the Edwards Aquifer, which is the main source of water for San Antonio and an important source of water for Austin,” Wilcox says. “We’re really trying to figure out how water moves through this landscape and where it goes.”

In its simplest form, groundwater recharge is driven by the movement of water through soil and into the underlying rock matrix where the water rests in an interconnected, saturated “sponge”—the aquifer. But that recharge only happens in certain areas, like streambeds, where there is no insoluble calcic layer below the soil and limestone, preventing groundwater from moving into the deeper aquifer layer.

In much of the Karst limestone formation that makes up the Edwards Plateau, water moves laterally through the highly porous limestone formations, moving to streambeds and eventually recharging the artesian aquifer.

Above the limestone, there’s a thin layer of topsoil, no more than 40 cm deep. As woody plants encroach on the delicate, biodiverse grasslands of the Texas savanna, you can’t help but wonder: where in the world are the oak and juniper getting enough water to live?

Rock moisture in the vadose zone is likely responsible for supporting plant life in regions with shallow soils. One study in Water Resources Research even found that the moisture held within rocks was responsible for supporting an entire Mediterranean forest. That study found that the oak forest in northern California tapped the 2–4 m of shale bedrock for water during the dry season. The bedrock saturated over the wet winters, serving as a source of water during extended dry periods when the 50 cm of topsoil dried out (https://bit.ly/3HExI7N).

The more water that’s taken up by plants, the less there is available for groundwater recharge. A recent study in Nature showed, using a complex model, that tree and shrub movement onto drylands could have a greater impact on water availability than climate change in these areas (https://bit.ly/34HRuko).

The stakes are high for understanding rock moisture in the vadose zone. Previous studies have inferred just how much water the rock below the soil can store. Some have looked at stable isotopes found in water transpired by plants during dry seasons, inferring that moisture must have come from rocks. Others have taken discrete, single measurements. But few have monitored, continuously, just how much rock moisture is available over time.

Pedro Leite was up to the challenge.

Installing Moisture Sensors in Limestone

If you want to continuously monitor rock moisture throughout the root zone, you’ve got to find a way to get moisture sensors into the rock.

It’s not a simple task. You can’t drill straight down because you’d disturb the soil and rock above the monitor, which wouldn’t give you accurate readings. You’d create a soil pore with preferential flow, directing water straight to the moisture sensor.

“We wanted to make sure we were measuring moisture throughout the whole root zone,” Leite says. For the deep-reaching roots of woody perennials at their site, that means digging to at least 80 cm.

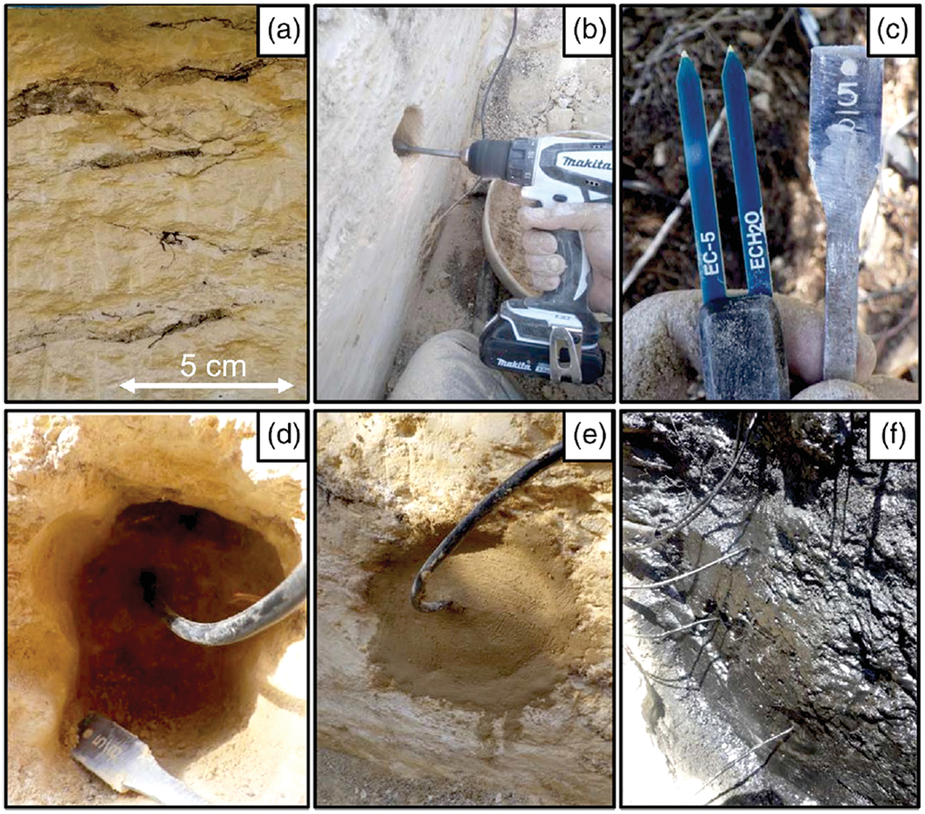

So Leite commissioned a backhoe. The team dug long pits in the soil, down through the limestone below. About a fifth of the soil at their site contains cobble-sized limestone rocks. Below the soil is weathered limestone.

The Buda formation of Karst limestone is highly variable near the Sonora, TX field site. In some places, it’s simple to take a backhoe and dig out a trench. In others, the rock below the soil is so hard, it’d take a lot more than a backhoe to get into it.

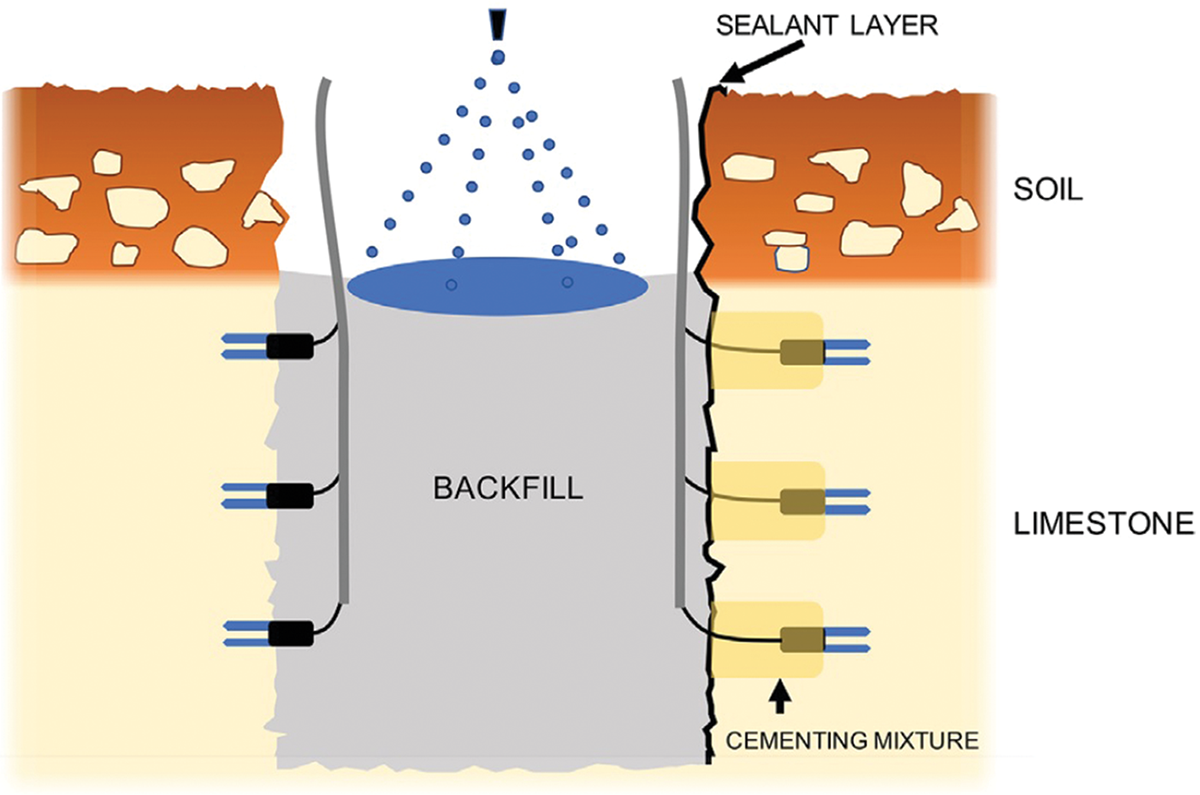

But the team managed to dig four suitable pits. Leite then used a drill with a bit sized to fit an EC-5 moisture sensor (from METER group). He drilled a horizontal hole in the limestone matrix of the vertical pit face and then used an insertion tool that Leite made himself (with a ⅝-inch spade drill bit) to create a “pilot slit” for the sensor prongs to fit into at the back of the hole. Because accurate readings only come from sensors in good contact with the medium, the team packed the pilot slit with a cementing mixture made of water and limestone powder before inserting the sensors. They then used this same limestone mixture to pack around the inserted sensor before spraying the entire wall of the pit with a sealant spray.

In fact, Leite tested the sealant in the lab on some limestone rocks to make sure it wouldn’t seep into them, corrupting their readings. It was thick enough that it stayed in place while still preventing water from seeping into the porous limestone rock.

“I’d used the leak seal for roofing before, and it was the first thing that came to mind to seal off the sensor from the backfilled material,” Leite says. “It’s crazy what you can find in a hardware store that works in the field.”

Speaking of backfilling, the team filled the pits back in with limestone and soil to prevent the pit face from weathering.

By then, it was time to put it all into practice.

Rock On, Moisture Readings

“We measured moisture in both limestone matrix and fractures,” Leite says. The team first tested out the sensors using an artificial dose of rainfall over the backfilled material. They wanted to see if the sealant did, indeed, prevent preferential flow. Their initial experiment showed that the moisture probe at the 40-cm depth in an unsealed pit face had massive fluctuations in water content compared with those in the sealed pit face. The sealant did the trick: no preferential flow.

Then they waited for rain.

On 9 Sept. 2020, storm clouds rolled in over Texas. Over two days, these clouds dropped 95 mm of precipitation, which was 41% of the total 234 mm measured during the team’s seven-month study.

The storm gave them the perfect test of rock moisture under field conditions. The team found changes in transient water storage, as measured by the installed sensors in 10-minute intervals, were consistent with the total amount of precipitation from the September storm. They also found some differences in the behavior of limestone fracture versus limestone matrix. Limestone fracture behaved like soil during the drying process—it dried out much more quickly than the porous limestone matrix. In fact, in the fall, the limestone matrix actually increased in volumetric water content by 0.01 cm3 cm–3. In the fall, the team postulates that more moisture was drawn by vegetation from the soil layers compared with the rock while in the summer, when soil moisture was depleted, rock moisture became an important source of moisture content.

Finally, the team noted that there were a few locations where moisture readings increased at deeper depths before shallower depths—a strong indicator of preferential flow.

“Water moves so much faster through fractures than through the limestone matrix,” Leite says. Though the team sought to avoid installing sensors directly in a limestone fracture (and fractures are easy to spot since they typically have roots growing in them), there were likely some locations where fractures beyond the soil pit wall created preferential flow.

In places where peak soil moisture was reached quickly, drainage was also fast. The in situ measurements give us a much better idea of how water moves through these porous limestone systems, and the seven-month span of study provides detailed insights into how plants might be taking up water from limestone matrix and the soil atop it.

Overall, the study provides insights for a unique adaptation of soil moisture monitoring tools that soil scientists (and ecohydrologists) around the country and world could adapt for their own systems. The sensors the team used were inexpensive, the readings were accurate, and the methodology is sound.

“We really weren’t planning to publish this—we just wanted to see if it was possible to get these measurements in limestone,” Leite says. “But other groups can use it—it’s totally doable to measure rock moisture with pretty affordable soil moisture sensors.”

Dig deeper

Read the original Vadose Zone Journal study “Applicability of Soil Moisture Sensors for Monitoring Water Dynamics in Rock: A Field Test in Weathered Limestone” here: https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20164.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.