Extractable metals and soil organic carbon: Understanding the relationship

A relatively simple way to predict soil organic carbon (SOC) would help farmers, land managers, and researchers make informed decisions while saving time and labor.

Very small soil minerals rich in aluminum and iron are known to protect soil carbon from decomposing too quickly—chemical extraction of the metals from those minerals can be used to predict SOC.

The complexity of soil and its interactions with metals can make these predictions fraught, and so a new article in Soil Science Society of America Journal seeks to better determine the relationships between extractable metals and SOC concentrations.

Being able to predict soil organic carbon in a relatively simple way can save time and labor and allow everyone from farmers and land managers to soil scientists and climate modelers to make informed decisions. Very small-sized soil minerals are known to protect soil carbon from decomposing too quickly, keeping it in the soil longer. The smallest and most reactive soil minerals are rich in the metals aluminum and iron, which are easily chemically extracted from soil and can be a method for predicting soil organic carbon.

However, the complexity of soil and its interactions with metals can make these predictions fraught. Two scientists, Steven J. Hall of Iowa State University and Aaron Thompson of the University of Georgia, recently partnered on a Soil Science Society of America Journal paper to answer the question: What do relationships between extractable metals and soil organic carbon concentrations mean?

“Soil scientists often use measurements of chemically extractable metals from soil to characterize the minerals that are present, especially for minerals that are hard to detect by x-ray diffraction,” Hall explains. “Because extractable metal data is easier and cheaper to collect, it is often used to help us understand why certain soils may accumulate more organic carbon than other soils.”

But he adds that because these chemical extractions also dissolve metals from organic complexes—rather than just the short-range-ordered phase mineral thought to be the best predictors—the interpretation of metals in soil extractions can be difficult and often varies among studies. Short-range-ordered phrases have a regular repeating crystal structure that is only over a short distance, such as just a couple nanometers. They usually have a very high specific surface area and that is thought to greatly contribute to their reactivity toward organic matter. This means they tend to accumulate organic matter on their surfaces or contain organic matter between their aggregated structures.

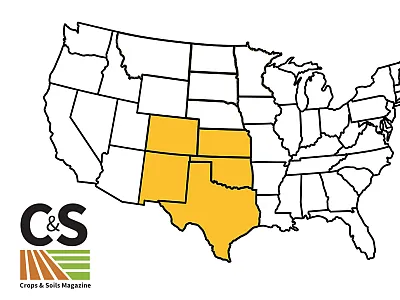

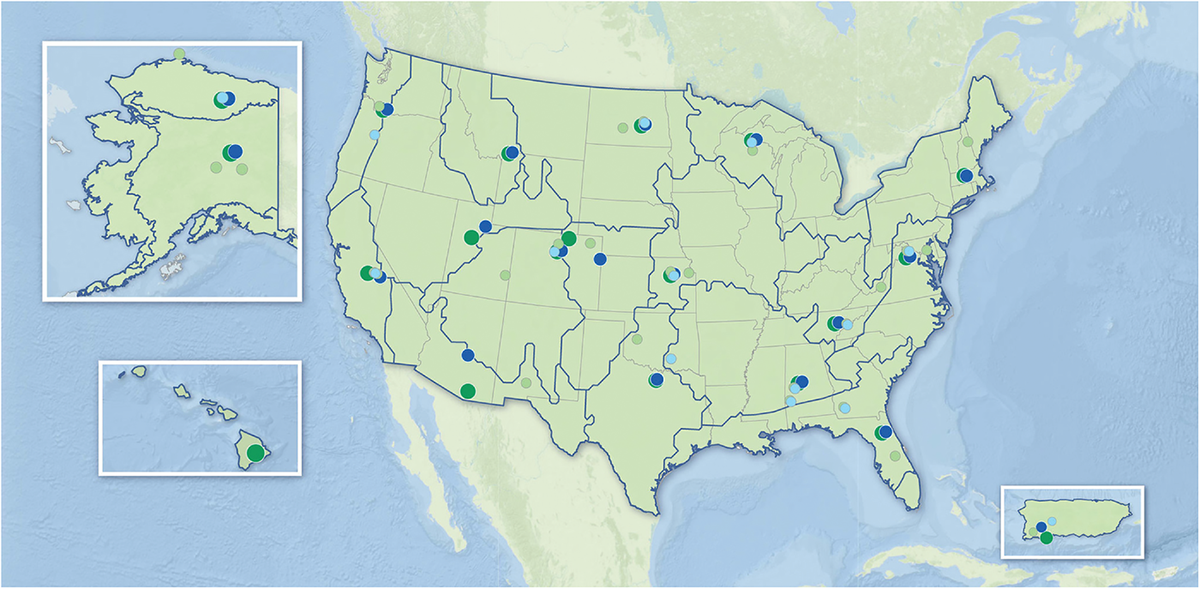

The researchers wanted to better understand how these extractions were related to soil carbon. A large soil database of North America from the National Ecological Observatory Network allowed them to better understand these relationships.

They note that it represented a unique opportunity to study diverse soils across the United States because the data spans many climates, from the tropics of Puerto Rico and Hawaii to the tundra of Alaska. The dataset follows a consistent sampling and analysis strategy across all its sites.

Oxalate and citrate-dithionite solutions are commonly used to extract aluminum and iron from soil. They both extract both metals but each solution is designed to extract different forms. For example, the citrate-dithionite extraction was devised to chemically reduce certain iron phases, but aluminum can also be dissolved. Oxalate is designed to dissolve short-range-ordered minerals specifically but also has been found to dissolve the metals in organic complexes, which is what can confound results. Oxalate-extractable aluminum and citrate-dithionite-extractable aluminum are atoms of aluminum that are dissolved by oxalate solution and citrate-dithionite solutions, respectively.

“The key to extracting chemicals from soil is that certain minerals or complexes or compounds will dissolve, meaning become fully solubilized in the aqueous phase, in some chemical solutions but not in others,” Thompson says. “We compared measurements of metals in these different extractions to better understand the forms of aluminum or iron that best predicted soil carbon among samples.”

Aluminum a Better Predictor Than Iron

Their results overall show that aluminum in both dissolvable forms, oxalate-extractable aluminum and citrate-dithionite-extractable aluminum, are better predictors of soil organic carbon than iron. This is true despite the two solutions extracting different mineral phases. In addition, the results were consistent across a diverse range of soils, including those not rich in short-range-ordered phase minerals.

From those findings, the researchers deduced that organic complexes may actually be playing a large role in predicting soil organic carbon. They also raise the question of if soil organic carbon may be controlling oxalate-extractable aluminum and responding to it, depending on the exact soil composition.

“Our key point is that indeed these correlations likely reflect organic carbon associations with short-range-ordered minerals in some cases, but also may result from contrasting mechanisms where biology is a driving factor,” Thompson says. “What we mean is that biology can generate organic acids that also dissolve short-range-ordered minerals and bind aluminum in organic complexes. This means biological weathering of soil minerals may account for the positive oxalate-extractable aluminum and soil organic carbon relationship in some soils, and biological reactivity of certain iron minerals may disrupt relationships with soil organic carbon.”

Aluminum may be a better predictor than iron because iron is redox reactive, meaning it can dissolve in the absence of oxygen when used as an electron acceptor, but aluminum is not. Aluminum is also more soluble than iron and often dissolves more readily via weathering of soil minerals by organic acids.

“Many papers in the literature have interpreted these soil extractable metals in different ways and have often glossed over the differences among extractions and the metals within the extractions,” Hall says. “Our results suggest that these nuances are likely important for understanding the mechanisms that lead to accumulation and loss of soil organic matter in different environments.”

Don’t Add Iron and Aluminum to Soils Quite Yet

The scientists note that their results may not be directly applicable to producers and land managers, who are best off using established methods that increase organic matter inputs, such as manure application, and decrease rapid organic matter decomposition. The research is not at a point where they would recommend adding minerals like iron and aluminum to soils, mainly because they can be toxic to plants and expensive.

“Our results may be more applicable to earth system modelers, who are tasked with predicting how organic matter will change in different regions of the globe in part based on soil type and composition,” Hall says. “The possible role of organic matter inputs in altering soil mineralogy and its subsequent capacity for carbon protection needs more attention.”

The aluminum and iron in soils across the world are naturally occurring from the weathering of rocks. Aluminum is the third most abundant element in soils and the earth’s crust, followed by iron as the fourth most abundant. In nature volcanic ash deposits, which are very high in short-range-ordered minerals, have been shown to increase soil organic carbon. However, applying volcanic ash to soil would be very expensive, the researchers say. Other work Hall and Thompson have published has shown that direct addition of iron to soil might play such a large role in decomposition that it doesn’t lead to increased carbon in soils.

They plan to continue to work to understand the mechanisms that allow for soil carbon to accumulate in soils because it is so critical to soil fertility and how soil carbon responds to a changing climate.

“We hope to use additional geochemical methods to characterize what forms of elements these extractions dissolve, and to better understand the role of biological factors in influencing these extractable metals,” Thompson says. “We both love soils and want to help chart a course for scientists to understand them better.”

Dig deeper

Cedric Evan Park, Barret M. Wessel, Martin C. Rabenhorst, Subaqueous pedology and soil‐landscape model evaluation in South River, Maryland, USA, Soil Science Society of America Journal, 10.1002/saj2.20520, 87, 3, (600-612), (2023).

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.