Rosenzweig awarded 2022 World Food Prize

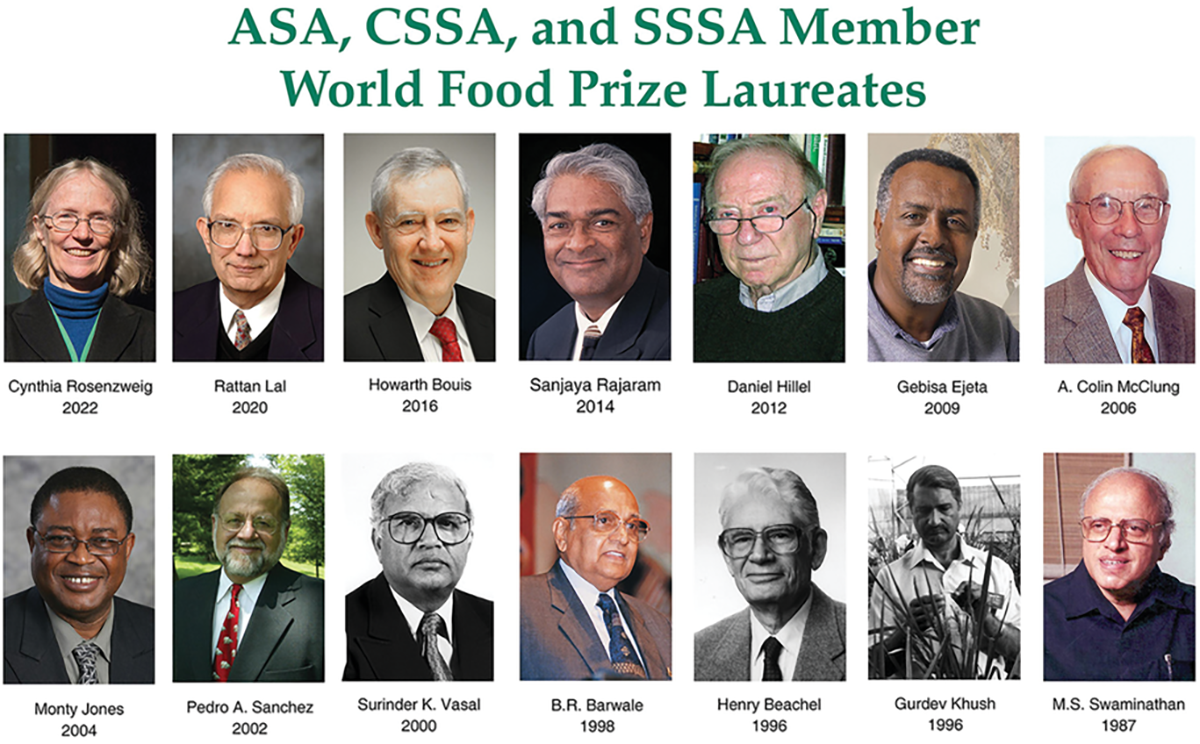

Dr. Cynthia Rosenzweig, ASA Fellow and Society member (ASA and SSSA), has been named the 2022 World Food Prize Laureate for her pioneering work in modeling the impact of climate change on food production worldwide. She was recognized for leading the global scientific collaboration that produced the methodology and data used by decision-makers around the world. Awarded to individuals who have improved the quality, quantity, and availability of food across the globe, this honor is often called the “Nobel Prize for Food and Agriculture.”

Rosenzweig spent four decades cultivating our understanding of the biophysical and socio-economic impacts that climate change and food systems have on each other—most recently by founding the Agricultural Model Intercomparison and Improvement Project (AgMIP), a global, transdisciplinary network of more than 1,000 leading researchers in climate and food systems modeling.

Models are powerful computational tools used in climate, agricultural, and economic research to conceptualize current interactions and project future trends. Rosenzweig is an innovator in modeling science, leading vital studies that have shaped the global debate on climate change and agriculture. An agronomist and climatologist, she has been a leader in the field of food and climate since the early 1980s. She has shaped our understanding of the tight relationship between food systems and climate change—that is, severe fluctuations in climate threaten our capacity to feed and nourish humanity while effective mitigation and adaptation strategies both curb climate change and enhance sustainable food production.

Rosenzweig realized early on that climate change is one of the most significant, pervasive, and complex challenges currently facing the planet’s food systems. She completed the first transdisciplinary model projections of how climate change will affect food production in North America and globally, and she was one of the first scientists to document that climate change was already impacting the cultivation of our food supply. Her early work contributed an important methodological breakthrough in early climate change impact assessments and established the foundations for current work in this field.

Now a Senior Research Scientist and head of the Climate Impacts Group at the Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS), part of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Rosenzweig started her career as a farmer. Her research centers farmers to plan and implement groundbreaking mechanisms that foster resilience to climate change.

Confronting Climate Change

When Rosenzweig was a graduate student working for GISS in the early 1980s, she heard the GISS Director Jim Hansen ask an important question upon which she ultimately based four decades of her career: With the climate changing so dramatically, what will happen to food?

In 1985, Rosenzweig published her first journal article on modeling the potential impacts of climate change on wheat-producing regions of North America and how wheat-growing crop zones might shift with a changing climate. She soon broadened her focus to modifying crop models, with agronomists Joe Ritchie, Jim Jones, and others, to more accurately forecast disparities in yield by including responses to increasing CO2 and global climate model projections. In this work, she identified the importance of using multiple models in research to achieve greater scientific rigor and more meaningful forecasts.

“We were using more than one model because if you only use one model, you start to believe it!” Rosenzweig says.

In the United States, Rosenzweig has played a critical role in the growing understanding of and sensitivity to what is needed for strengthening resilience to climate change. She led the agriculture sector’s work in the USEPA’s first assessment of the potential effects of climate change on the United States in 1988, creating the earliest projections of the impact of climate change on the nation’s agricultural regions.

A Conversation with Cynthia Rosenzweig

| By Kristen Coyne

Cynthia Rosenzweig traces her connection to the Societies back to 1981 when, as a graduate student and young researcher at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS), she first joined ASA. In the decades since, she has also been a member of CSSA and SSSA, served on numerous committees, attended dozens of Annual Meetings, edited a collection of papers highlighting women in agriculture, and in 2015, received the ASA Presidential Award with fellow co-founders of the Agricultural Model Intercomparison and Improvement Project (AgMIP). After Rosenzweig was announced as the 2022 World Food Prize Laureate, she sat down with CSA News magazine to discuss how the Societies have benefitted her science and career.

CSA News: How did the Societies help you as a young scientist?

Rosenzweig: I remember vividly going to my first Annual Meeting. I had marked out all the sessions I wanted to go to in the program, and I went to every single one. And I went to every single booth in the exhibit hall.

I realized from going to lots of different sessions that Division A-3 was my professional home—at that time it was called Agroclimatology and Agronomic Modeling. I had already started to do research on climate change and how it would affect agriculture.

I was already based at GISS, where one of the first global climate models was in use. [GISS Director] Jim Hansen was asking, “How will these early projections of climate change with increased greenhouse gases affect food?” When I went to the ASA Annual Meeting, I was looking to find out: How could I answer that question?

I learned there about Joe Ritchie and Jim Jones. Both are really early developers of crop modeling in the U.S. and became some of the seminal people in my career. I realized we had to have modeling tools that responded to both climate and crops. I went up to Joe Ritchie and said, “Could we have a coffee or a lunch?”

So, we met, and I spoke to him about bringing the two types of modeling together. That’s one way that ASA helped me tremendously.

When I would go to the Annual Meetings, I would always sign up for the field trips because they were so amazing. That was how I met Daniel Hillel, on a field trip at a meeting in Las Vegas. We went out into the mountains, and the soil pits were dug, and it was starting to snow—it was great! He was a very, very important member of the Societies who won the World Food Prize 10 years ago and was an important mentor to me.

CSA News: You published your first paper about the effects of climate change on crops back in 1985 and worked within ASA to draw more academic attention to the topic. What was it like being one of the early voices advocating for more scholarship on climate change and crops?

Rosenzweig: I think I was the person at ASA to organize the first sessions on climate change and agriculture. There had been, previous to that, quite a bit of work on high CO2 and crops. But what I was really bringing was that we had to look at both the effects of increases in CO2and the climate changes on crops at the same time.

In the beginning, it was very new, and I think there were good scientific questions, like whether climate change was “real.” I trained a group of crop modelers that I met at ASA and, with Joe and Jim, started doing the very first projects on it. After that first paper in 1985, I received funding from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and in 1990, we published the first U.S. set of projections on how climate change would affect U.S. agriculture. We started on that, and from that time, there developed at ASA a group of researchers working on climate change and agriculture.

But it did take time in the early days. There were some skeptics. But because I’ve worked in climate change for my whole career, the way I deal with that is: Just keep going, keep discussing, keep engaging in scientific dialogue. I was such a long-term member of ASA and would come every year. And little by little, year after year, I think many scientists came to realize what an important challenge climate change is for agriculture.

CSA News: In 2010, you founded AgMIP along with Jim Jones, John Antle, and Jerry Hatfield. What is AgMIP, and how can Society members contribute?

Rosenzweig: AgMIP is a global collaboration of more than 1,000 researchers who work to improve the projections of how climate change will affect food. And now we are including how food affects climate change through greenhouse gas emissions. AgMIP is organized into modeling teams, and it is truly transdisciplinary because we have climate specialists, crop and livestock specialists, economists, pest and disease teams, and a water team. And there’s an evapotranspiration team featuring Jerry Hatfield and other Society members to bring experimentalists and modelers together. That’s a perfect example of ways that Society members can form AgMIP teams on key topics related to climate change and agriculture.

For a long time, in the development of crop models, each group worked on its own model. These groups would talk to each other, but it would be kind of like, “Our model is better than your model.” Finally, the models were developed enough, and the modelers were ready to create a new kind of science with the models. At the heart of AgMIP is the multi-model ensemble because we bring the community of modelers together to develop agreed-upon, joint protocols. Everyone keeps using their own models, but everyone does the same thing in terms of their simulations of climate change and agriculture. This really enabled the science of the projections to advance in rigor because now we have the ensemble of models all being tested in the same way.

CSA News: You have talked a lot about the power of community and collaboration in research. How have you experienced that in the Societies?

Rosenzweig: I truly believe that the spirit and culture of ASA is collaborative. ASA is all about creating and sharing knowledge and respecting everyone’s work and realizing it’s all coming from different directions, from different angles. I really learned a lot about those cultural aspects of cooperation. A lot of the way that AgMIP actually functions reflects the culture of ASA.

CSA News: What can organizations like ASA do to encourage the next generation of agronomists and other scientists who will be needed to build on your work?

Rosenzweig: When I mentor young professionals, I encourage them to join their professional society. I feel it is this tremendous career-building asset that everyone needs. The thing is, though, to go every year because you are creating your professional community for your entire career. That is what I did at ASA. I think we can do more to encourage the young people to do that.

ASA is—rightly—very tied to the land grant universities. But now, because food in agriculture is such a growing, emerging topic of interest among young people, there are other universities starting food programs. For example, I’m an adjunct senior research scientist at the newly founded Columbia Climate School, and one of their main programs is healthy and sustainable food—right in the middle of New York City! I think we should do outreach to the students at universities like Columbia and other places that are starting food programs.

CSA News: Throughout your career, you have served as a bridge between groups of people—between scientists from various disciplines and countries, for example. Why is bridge building key to your work, and how could the Societies help?

Rosenzweig: Climate change is so challenging: We must solve it, but no one group or discipline or sector of society is going to be able to solve it on their own. In my role as co-leader of AgMIP, I work with groups all over the world, and we need to be learning from each other. So, let’s work together to really reach out, through ASA, to even more international colleagues and participate in more international events. Maybe ASA could go on the road and go to other countries? AgMIP would love to work with ASA on bringing its great science to help work on climate change around the world.

Also, there are big silos between researchers who work on impacts and adaptation and those who work on greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation. AgMIP is creating a program that brings mitigation and adaptation together, called Mitigation and Adaptation Co-Benefits, or MAC-B. We’re looking to Society colleagues to work together to see how the reduction of greenhouse gases can be done most effectively under changing climate conditions. We have to help figure out how we can mitigate and adapt to climate change at the same time.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

She brought the issue of climate change to ASA’s attention and organized the initial sessions on the issue in the 1980s. She also enlisted economist Rich Adams to bring together climate, biophysical, and socio-economic models to produce the first economic projections for agriculture in the United States, published in Nature in 1990.

Rosenzweig kept her eye on impacts in other parts of the world as well as the U.S. She co-authored the first-ever study assessing the potential impact of climate change on the world food supply, published in Nature in 1994, applying the same methods used in the U.S. national assessment to a global scale. The results of this study made it very clear that low- and middle-income countries would bear the brunt of climate change and suffer disproportionate negative effects.

An important mentor and colleague was 2012 World Food Prize Laureate Dr. Daniel Hillel, with whom Rosenzweig collaborated on many studies. She first partnered with him in 1993 to compare model projections to real-world climate disasters such as the Dust Bowl. They found that the Dust Bowl could be considered a preliminary analog to the effects predicted by the climate change models, setting the world on a trajectory of more and more severe droughts and extreme crises in agriculture.

Her research brought the threat of climate change impacts on food to the world’s attention through her participation on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Rosenzweig was coordinating lead or lead author on three global assessments, including the IPCC Fourth Assessment in 2007, which received the Nobel Peace Prize. Her work with IPCC contributed to the scientific foundation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the process which led to the Paris Agreement on Climate Change in 2015. Her research directly supports work in more than 20 countries to develop National Adaptation Plans and National Determined Contributions for the UNFCCC.

Rosenzweig recognized the necessity of going beyond modeling to determine what observable impacts were already coming about as a result of warming temperatures. As a coordinating lead author of Working Group II for the 2007 IPCC Fourth Assessment, she and co-authors compiled a database of more than 28,000 entries of observed physical and biological changes occurring on all continents and most oceans. She was able to show that a significant number of these shifts were attributable to anthropogenic climate change at the global scale, and in 2008, she and her team published a study that extended these results to continental regions.

The AgMIP Advantage

During a coffee break at a conference in Florida in 2008, Rosenzweig had the idea for what would become the gold standard for agricultural and climate modeling research and application. She immediately began building a vast network, and in 2010 founded AgMIP, a global community of experts dedicated to advancing methods for improving predictions of the future performance of agricultural and food systems in the face of climate change.

“Modeling groups have brought their crop models to AgMIP so that we can work on them together for the first time,” Rosenzweig says. “Before, each modeling group would be working separately. Now we’re all working together jointly so that we can nail uncertainties, understand the processes, improve the models, and thus make better projections, so we can develop adaptation strategies for all different regions of the world.”

By comparing multiple models brought together under AgMIP, Rosenzweig and AgMIP teams developed protocols to understand and improve model performance in diverse conditions, especially in situations where limited data are available, as is the case in many rural and tropical areas. AgMIP also coordinated global and regional assessments across many different disciplines and scales. This work began to answer the question of how we can manage risks and develop resilience to extreme weather, climate change, and other disruptions to agricultural production and food security now and in the future.

Rosenzweig knew that creating more accurate models that produced more detailed data, while important, would mean nothing without action. She therefore brought researchers to collaborate with other stakeholders, including policymakers and on-the-ground practitioners, in order to address the complex challenges of climate change and ensure that their approaches were farmer focused. Incorporating stakeholders’ knowledge greatly enhanced the effectiveness of adaptation interventions and created trust and buy-in among stakeholders for these methods.

“Previously, scientists would produce a result, and then they would pass it off to society,” Rosenzweig says. “Such ‘silos’ do not work for finding solutions to climate change. What we’ve learned is that there needs to be far more interaction and integration among different groups of society as we confront the climate change challenge.”

Her work with AgMIP is applied at local, regional, national, and global scales and covers many different crops, soil and water processes, farming systems, biophysical parameterizations, climate, economics, and policy. AgMIP programs are carried out in more than 20 low- and middle-income countries, involving over 200 policymakers and practitioners.

Through AgMIP, Rosenzweig has created the most clear and cost-effective way to understand climate risks in current and future scenarios and make sure that investments and public policies will appropriately serve different groups of farmers now and in the future. AgMIP projections of potential trade-offs between environmental, socio-economic, and productive variables when different actions are prioritized are key for ensuring that progress on food systems under climate change is equitable, inclusive, and sustainable.

In Pakistan, for example, the research results of the AgMIP team under Rosenzweig’s leadership led the government to take steps toward mitigation and adaptation of agriculture and food systems to climate change. These actions included updating land-use planning tools, supporting the breeding of new climate-adapted crop cultivars, and publishing many recommendations in local language bulletins to benefit the farming community.

In several countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, Rosenzweig led teams to develop an innovative Regional Integrated Assessment (RIA) methodology for climate change impacts. The RIA was so comprehensive and well received that stakeholders in Ghana and Senegal, among others, called for scaling up and building capacity to apply the methodology to more regions. These research tools are being applied for designing policies to make farming and food systems more resilient to shocks related to climate and COVID-19 in Zimbabwe and other countries.

Due to the dynamic nature of climate change, Rosenzweig is constantly challenging AgMIP to evolve and develop new cutting-edge tools such as the AgMIP Impacts Explorer, an interactive decision-support tool that visualizes key research findings and data for educators, policymakers, and technical practitioners.

Molding a Modeler

Cynthia grew up in Scarsdale, New York, in the United States. Her father, George Hardy Ropes, was a mathematics educator who introduced computers to many elementary and secondary school districts. Rosenzweig collaborated with him in 1990 to develop one of the first educational software programs on climate change, called Hothouse Planet. Her aunt, Alice Recknagel Ireys, was a renowned landscape architect. Both of them encouraged Rosenzweig’s early interest in math and nature. Her mother, Catherine Ropes, instilled her people skills and love of food shared with friends and family.

Rosenzweig was further inspired to cultivate her interests by her fifth-grade teacher, Mrs. Jean Clancy, who put daily math puzzles on the blackboard and took her classes on frequent nature walks. Rosenzweig also joined the Girl Scouts, through which she continued to explore the natural world.

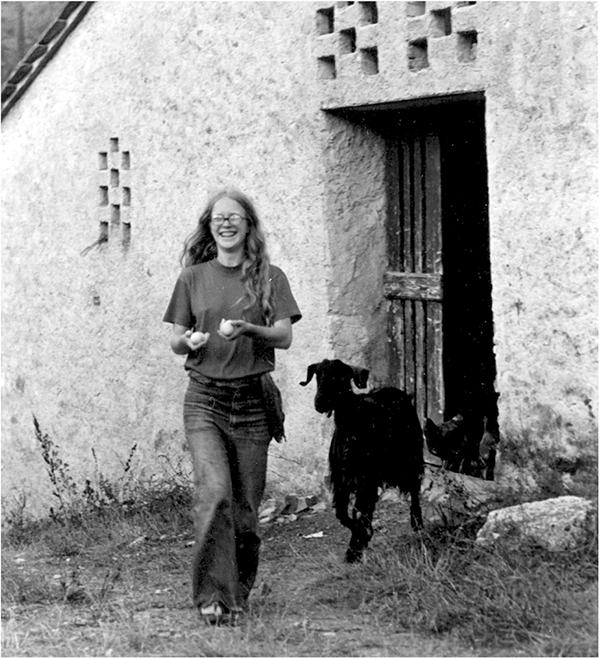

Rosenzweig attended Stanford University in the 1960s, where she met her husband, Arthur. The couple decided to move to Tuscany, Italy, where they started a farm, growing vegetables and fruits and raising chickens, goats, and pigs. This experience was where Rosenzweig fell in love with agriculture and realized she wanted to spend her career in this field.

When they returned to New York in 1972, Rosenzweig went back to school, obtaining a two-year degree in agriculture from a technical college on Long Island where she learned practical skills such as tractor maintenance and pruning of apple trees. She and her husband and friends then started Blue Heron Farm in Thompson Ridge, New York, where they grew sweet corn, Indian corn, and cucumbers for pickling.

To continue her education, Rosenzweig enrolled in Rutgers University and earned a B.S. in Agricultural Sciences in 1980 and an M.S. in Soils and Crops in 1983. During her graduate studies, she began working for GISS. She received her Ph.D. in Plant, Soil, and Environmental Sciences from the University of Massachusetts in 1991.

The energy and insight that Rosenzweig has applied throughout her career to revolutionizing food systems, urban centers, and research processes to address climate change, one of the greatest challenges facing us today, is helping farmers, policymakers, researchers, and many more build the resilience that is needed both now and in the future to feed the world.

“The climate is already changing,” Rosenzweig says. “We have a responsibility to respond and to prepare for the increasing risks of the future. Let’s roll up our sleeves and tackle this challenge now.”

The following article was edited for length and consistency with this magazine’s style. View the full presentation on the website of the World Food Prize at www.worldfoodprize.org/en/laureates/2022_rosenzweig/.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.