Living mulch in corn boosts soil health, cuts inputs

- Well-managed cover crops bring producers a host of soil health benefits but require extra planning and yearly reseeding and termination.

- Living mulch—a perennial plant covering the soil year-round, even during crop production—could bring the benefits of cover crops without some of the drawbacks.

- A series of Agronomy Journal research demonstrates how producers in both the Midwest and the Southeast United States could use clover living mulch in their corn crops.

Keep your soil covered. Sounds simple, right?

We know cover crops improve soil health indicators like moisture retention and aggregate stability; they increase soil organic carbon and decrease erosion. They help retain nutrients in the soil, and legume cover crops even give producers some bang for their buck by cutting their nitrogen inputs for the next crop.

But there are downsides. Producers have to buy seed, make extra passes through the field after harvest to plant them, and terminate cover crops in the spring before sowing a cash crop. It takes more planning, more time, more labor, more expense.

There could be another way. With living mulch—a perennial plant that grows in the field alongside the cash crop—producers might be able to gain the benefits of cover crops without the yearly rigamarole of reseeding in the fall and terminating every spring.

In the driftless region of southwest Wisconsin, producers traditionally rely on tillage for planting silage corn and alfalfa. Silage production is particularly rough—the soil is tilled in the spring and cleared bare of residue after harvest in the fall. Photo courtesy of Adobe Stock/Dimid.

Agronomy Journal has seen some groundbreaking work (without the tillage) incorporating perennial clover in corn systems, dating back to the year 2000. Two research teams—one at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, another at University of Georgia—show us how living mulch could work in corn systems in two distinct parts of the United States.

From Pasture to Field

Kura clover, Trifolium ambiguum M. Bieb, is a legume that originated in southeastern Europe and western Asia. It’s stocky, grows only a foot high, and spreads just under the soil surface through rhizomes. Pollinators love its sweet nectar, livestock and deer delight in its tender leaves, and producers appreciate its perreniality.

In fact, Colorado State University agronomy professor Wayne F. Keim wrote in 1954 about Kura clover’s excellent properties. He mentions that one producer’s cattle made their way into a neighbor’s experimental honey plant garden. The cattle “found the plots of T. ambiguum and pastured them cleanly.”

In the mid 1990s, a doctoral student at University of Wisconsin–Madison thought Kura clover could be suited for more than forage.

“Rob [Zemenchik], my Ph.D. student at the time, was really interested in soil erosion,” recalls ASA and CSSA Fellow Kenneth Albrecht, a professor in the Department of Agronomy. “He said, ‘wouldn’t it be great if we could develop a system where we have permanent ground cover into which corn is planted?” Kura clover has the right characteristics to work in such a system.

Erosion is constant concern in the driftless region of southwest Wisconsin where just a thin layer of soil perches on top of limestone. Other hilly areas in the state struggle with erosion, too. Producers traditionally rely on tillage for planting silage corn and alfalfa. Silage production is particularly rough—the soil is tilled in the spring and cleared bare of residue after harvest in the fall. The resulting soil and nutrient losses are both costly for farmers and hard on the water supply.

“In one really wet year, we saw 78 kg nitrate-N leach below the rootzone of conventional corn production. It was a 300% greater loss than we saw under corn in Kura clover living mulch,” Albrecht says. The N loss has big impacts. A recent report by the Wisconsin Groundwater Coordinating Council revealed that 10% of the private wells they sampled exceeded safe levels of nitrate, clocking in at more than 10 mg L–1 (https://bit.ly/3nDimHX).

Living mulch fights on both fronts—against N loss and erosion. Over the past 25 years, Albrecht took the clover and ran. Along with Zemenchik and other graduate students and colleagues, Albrecht has tested Kura clover as both a forage crop and a living mulch interseeded with corn, soybean, sorghum, and winter cereals.

In July 2000, Zemenchik, Albrecht, and their collaborators published an Agronomy Journal study, “Corn Production with Kura Clover as a Living Mulch” (https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2000.924698x). In spring 1996, the team had a two-year-old stand of Kura clover in which they tested various levels of glyphosate application to facilitate corn establishment and growth in this living groundcover. Spring-applied glyphosate suppresses, but doesn’t kill, the living mulch.

“Our big breakthrough was the availability of Roundup-ready corn in the mid ‘90s,” Albrecht says. “We found that for this system to be successful, you have to knock back the living mulch before you plant the corn. Roundup-resistant corn gave us flexibility to further suppress the clover or weeds after corn emergence.”

Their initial findings demonstrated that the researchers were able to use Kura as a living mulch for corn using glyphosate suppression with little to no impact on corn yield. Plus, Albrecht estimates that the N provided by the clover from dropped leaves, sloughed nodules, rhizomes, and roots, can provide 60–90% of a corn crop’s N requirements. But the whole system only works if growers keep a very close eye on the clover.

By 2010, Albrecht and his collaborators published another study examining the soil water balance and nitrate leaching in the Kura clover and corn system (https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2009.0523). They found that Kura clover tends to keep the soil moisture lower in the spring and high in the summer compared with the control system, which was killed Kura clover. It also reduced nitrate-N leaching by up to 74% compared with the control fertilized with ammonium nitrate.

In 2016, graduate student Arthur Shiller published his research on erosive soil loss and nutrient runoff from a hillside corn field in southwest Wisconsin (https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2015.0488). Kura clover living mulch decreased water runoff by 50%, soil loss by 77%, and P and N losses by 80% relative to monocrop corn.

“Really, there are two drawbacks to the system in Wisconsin,” Albrecht explains. “First, you have to give the clover a full year to establish, which means you have to get creative about income from that land. And you have to make sure you suppress it at the right time.”

Corn being strip-till-planted into a white clover living mulch system. Photo by Nick Hill.

In a well-managed system, a producer could apply glyphosate to established Kura clover in the spring when it’s about 2 to 4 inches tall. Albrecht estimates that there’s a two-week window in which you can suppress Kura clover before it gets too big for glyphosate to be effective.

The living mulch system is also attractive to organic growers, who struggle with weed suppression. Instead of using glyphosate, Albrecht and his students have tested other means of suppression, including mowing, flaming, and strip tillage.

Though Kura clover is the legume of choice in the northern Midwest, something different creeps along in the South.

Moving South

It was another graduate student that spurred ASA Fellow Nicholas Hill, now a professor emeritus at the University of Georgia, to try his hand at growing corn in living mulch.

“Chris Agee—he was one of my former graduate students—was working with Pennington Seed Company at the time,” Hill explains. “He came to me and said he’d read about some living mulch work in Wisconsin on Kura clover. We had this variety of white clover developed by the University of Georgia called ‘Durana’ that’s actually adapted to the Southeast. We wanted to give it a try.”

Unlike Kura clover, white clover creeps across the soil surface, repopulating bare patches of ground via stolons, not rhizomes. It establishes more quickly than Kura clover—it needs just one mild Georgia winter before you can plant a cash crop in the spring.

Over the past seven years, Hill’s team has put the living mulch system through its paces. They homed in on the agronomic requirements, water usage, and soil health impacts of using the system in the U.S. Southeast.

In 2014 and 2015, Hill’s team planted out Durana white clover on test plots in Georgia. Over two years of field trials, they discovered some best practices for using the system down South. They found that suppressing the living mulch using both glyphosate and dicamba prior to planting provided the corn with a competitive advantage, plus a nice boost of nitrogen from the legume’s biomass. They also found that using wider rows (90 cm) and smaller bands of herbicide (20 cm) resulted in the best outcomes. Their findings were published in a 2017 Agronomy Journal study (https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2017.02.0106). Of course, these variables are all dependent on water supply.

Both the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the University of Georgia researchers have demonstrated that a clover living mulch can supply anywhere from 50 to 90% of the total nitrogen inputs a corn crop needs to grow. This photo shows a significant thatch layer builds from the senescing clover as the season progresses. The thatch decomposes and nitrogen becomes available for corn nutrition. Photo by Nick Hill.

In 2018, the team published a follow-up study (https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2017.08.0475) comparing the soil water content of a white clover living mulch system with that of traditional cereal rye and crimson clover crops over two field seasons in 2015 and 2016. To do so, they planted both cover crops and the white clover living mulch in October of 2014 and 2015, prior to the corn crop. The following summer, the corn crop was planted out after either killing off the cover crops or suppressing the living mulch.

All told, they found that corn grain yield was lower in the living mulch system compared with traditional cover crops, particularly during the dry growing season of 2016. However, the white clover provided the corn with an extra boost of nitrogen when shading during the corn’s vegetative growth stages caused the clover to drop its leaves. This reduces the amount of N a producer needs to add to the corn.

Finally, we can’t talk about cover crops without talking about soil health. In their most recent work, published in 2021, Hill’s research team compared soil health outcomes after three years of growing either cover crops reseeded annually, or a continuous living mulch of white clover (https://doi.org/10.1002/agj2.20768).

They found that living mulch had lower soil bulk density, greater porosity, water infiltration, and labile carbon in surface soils compared with annual cover crops. For fields in need of speedy soil health interventions, living mulch could be the ticket.

Cowboy Economics

Drawbacks and benefits—living mulch has them. Bad news first: corn grown in living mulch systems typically yields slightly less grain compared with control or cover crop systems.

“People like to focus on yield,” Hill says. “But it’s profitability that’s key. Yield has traditionally been associated with profitability, but that’s not always the case.”

When you take a good hard look at what Hill calls the “cowboy economics” of a living mulch system, you start to get a clearer picture.

When it comes to inputs, both the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the University of Georgia researchers have demonstrated that a clover living mulch can supply anywhere from 50 to 90% of the total nitrogen inputs a corn crop needs to grow. Living mulch requires only one round of seeding every four years for white clover and can live indefinitely as Kura clover.

“We have pastures of Kura clover that are still going strong, and they were planted in the ‘90s,” Albrecht says.

Plus, University of Georgia weed scientist and Agronomy Journal coauthor Nicholas Basinger mentions the long-term weed suppression benefits of white clover in corn.

“We’re running some trials now, doing a weed demography study on Palmer amaranth in a field with no history of palmer amaranth,” Basinger says. “Basically, we’re tracking a set population of Palmer amaranth over several years of production, and so far, we’re reducing the population as much as 70% using living mulch.”

Palmer amaranth is essentially “public enemy number one” in the Southeast. It’s often herbicide resistant, and a really productive weed can produce as many as a million seeds in a season. Its growth can be explosive.

Taken together, living mulches look to be an effective means of cutting back on seed costs, input and herbicide expenses, and passes through the field for seeding and terminating. According to Hill’s preliminary calculations, these savings more than offset the small amount of direct profit lost when yields fall.

And remember how cows love it? Well, pollinators do, too. A thriving pasture of clover provides ample nectar, improving biodiversity in fields that might otherwise be monocultures. Basinger waxed poetic about the soft thrum of insect wings you hear when you walk through a field of white clover living mulch.

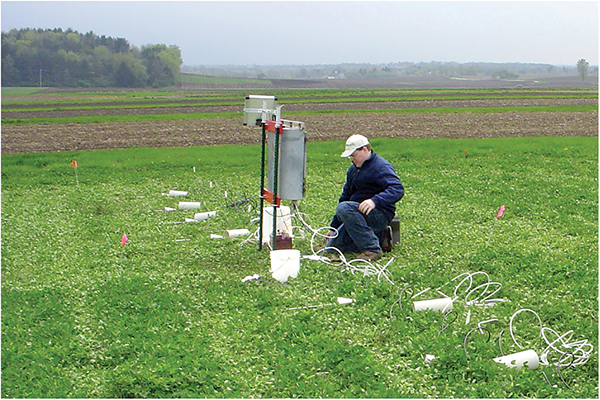

Soil moisture monitoring equipment being installed in a Kura clover living mulch experiment in Wisconsin. Albrecht and his team found that Kura clover tends to keep the soil moisture lower in the spring and high in the summer compared with the control system, which was killed Kura clover. Photo by Tyson Ochsner and courtesy of USDA-ARS.

Though it’s an unusual system, the benefits are stacking up. Some farmers near the University of Georgia are testing it out on their fields, and future studies are looking to test out the system’s efficacy in cotton–corn rotations. Keep your eyes peeled for more weed-suppression studies and agronomic trials with cotton, corn, and clover.

“For farmers to adopt these systems, there has to be more than an environmental benefit—there’s got to be an economic benefit to the system as well,” Hill says. “We’re at the point where we need to find a way to maintain food production without all the detrimental effects it can have on the environment, and I think this has the potential to do it.”

Dig deeper

Check out the Agronomy Journal studies mentioned in this article:

- 2021: “White Clover Living Mulch Enhances Soil Health vs. Annual Cover Crops”: https://doi.org/10.1002/agj2.20768

- 2018: “Water Use Efficiency in Living Mulch and Annual Cover Crop Corn Production Systems”: https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2017.08.0475

- 2017: “Optimizing Agronomic Practices for Clover Persistence and Corn Yield in a White Clover-Corn Living Mulch System”: https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2017.02.0106

- 2016: “Soil Erosion and Nutrient Runoff in Corn Silage Production with Kura Clover Living Mulch and Winter Rye”: https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2015.0488

- 2010: “Water Balance and Nitrate Leaching under Corn in Kura Clover Living Mulch”: https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2009.0523

- 2000: “Corn Production with Kura Clover as a Living Mulch”: https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2000.924698x

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.