Oceanic pedology: Is there a depth too deep?

While documentaries about the ocean’s dark blue depths are easy to come by on Netflix, the Discovery Channel, and BBC, you won’t find oceanic soils playing a starring role. Currently, soil surveys have a 2.5-m water depth cutoff, and subaqueous soils are ignored by many.

Part of the rationale is that aquatic plants are not found below this level of water. However, many soil scientists argue that because this is actually false, the cutoff should be re-evaluated.

The benefits of studying subaqueous soils run deep—from food production to sustainable mining and offshore wind farms to atmospheric models and predictions about climate change, and much more. But if soil scientists were going to wade into a discussion about a new cutoff, what would it be?

While documentaries about the ocean’s dark blue depths are easy to come by on Netflix, the Discovery Channel, and BBC, you won’t find oceanic soils playing a starring role. Many soil scientists say it’s a real missed opportunity and that an arbitrary soil survey water depth cutoff is partly to blame for oceanic soils missing their casting call.

Currently, soil surveys have a 2.5-m water depth cutoff, and subaqueous soils are ignored by many. There are some with a special interest in these soils who don’t feel constrained by the cutoff and are willing to go a bit deeper. Then there are others who advocate for going much, much deeper—all the way to the sea floor where 70% of the earth’s surface lies.

The cutoff is historical in nature, and part of the rationale is that aquatic plants are not found below this level of water. However, many soil scientists argue that because this is actually false, the cutoff should be re-evaluated. Marine rooted plants and algae like kelp can be found in up to 50 m of relatively clear water in parts of the world, for example. They say there would be multiple benefits to expanding the influence of pedology.

SSSA member Barret Wessel, currently a visiting assistant professor at the University of Mary Washington in Virginia, focused on subaqueous soils in estuaries for his doctorate degree at the University of Maryland and has a passion for ocean soils. At the 2020 Annual Meeting of ASA, CSSA, and SSSA, he gave a virtual presentation titled “Oceanic Pedology: Is There a Depth Too Deep?”

“We study lots of soils like Antarctic soils and desert soils that don’t support plants, and people are even talking about astropedology—soils on other worlds,” he says. “The issue with the 2.5-m cutoff is that it’s totally arbitrary, not based in science. If soil scientists and pedologists can contribute to our understanding of something, then I don’t see why they should limit themselves from doing so.”

Along with most of the seafloor, the cutoff also impacts areas of freshwater and estuaries, which is where it intersected with Wessel’s research. Proponents of re-evaluating the current cutoff say the same factors and processes that govern surface soils do not simply stop being important after 2.5 m of water. Below water of any depth there are complex microbial communities and multicellular animals living alongside each other. Soil chemistry also knows no depth threshold; many properties of deep subaqueous soils are driven by chemical reactions, much like any other soil. Wessel points out that the very set of processes used to define soil—addition, removal, translocation, and transformation—can all be observed in these soils.

Not all subaqueous soils are created equal, however, proving they are not a monolith and deserve further study. Wessel notes some differences between soils on the seafloor versus those in ponds or along the coast. For example, soils in ponds and along coasts are anoxic, meaning they lack oxygen, but much of the deep seafloor has available oxygen in it. The supply of carbon to the deep ocean is very low because of how efficiently the ocean utilizes waste products. That means that there is little carbon to feed microorganisms that use oxygen, and the result is that dissolved oxygen can be detected tens of meters into the seafloor.

“If you look closely, subaqueous soils are quite diverse and complex, and are much more than just mud. Mud is a lot more mysterious than you might think.”

Benefits of Studying Subaqueous Soils

The benefits of studying subaqueous soils run deep, Wessel says, with everything from short-, near-, and long-term benefits.

Much like the soils of farmland grow food, underwater soils and habitats can be valuable food sources for humans and livestock. This includes kelp, seaweed, and fish. Soil scientists who study underwater soils are already working with shellfish producers in some U.S. states, mostly along the East Coast. These land use interpretations can help make recommendations for the use of these soils, such as sustainable aquaculture, much like traditional soil surveys have helped farmers in multiple ways. Wessel sees a great benefit to these surveys and their findings trickling down from soil scientists to agricultural extension offices—and on down to producers and industries utilizing these aquatic resources.

While not all work on subaqueous soils is thoroughly sustainable, soil surveys can help determine where something like mining will cause the least negative impacts or which soils would be able to recover quickly. Because marine mineral mining can be incredibly destructive to seafloor ecosystems and pilot projects are already underway, a near-term benefit of oceanic pedology is the ability to characterize these environments before they are disturbed. This will help monitor the health of the soils and environment.

“Soil scientists have been instrumental in helping to develop better cropping systems, nutrient management plans, and so much more,” Wessel says. “As we develop the seas for uses ranging from aquaculture to mineral extraction, soil scientists can make similarly important contributions to those activities, helping ensure we work toward a sustainable civilization for future generations to inherit.”

In addition to mining, there are infrastructure projects like the offshore wind farms proposed by President Biden and his administration. These involve installing equipment on the seafloor to using dredged materials for various purposes. One key to the success of these projects, Wessel says, is using oceanic pedology to better predict the distribution and properties of subaqueous soils.

Studying soil microbes is of great interest on land and would have similar benefits underwater, according to Wessel. Being able to connect microbial communities and processes to chemical changes in the seafloor is key to developing better models of soil chemistry. This can have long-term benefits for atmospheric models and predictions about climate change.

“The marine science community has already done a lot here, and we want to be sure we’re making contributions, not trying to reinvent the wheel,” Wessel explains. “Soil scientists should embrace the marine science literature, build collaborations, and contribute what they can.”

Basing a New Threshold on Science

If soil scientists were going to wade into a discussion about a new cutoff, what would it be? Is there a depth where soil scientists’ knowledge is no longer useful for studying these soils?

“Think about it this way—is there some elevation at which soil science no longer applies?” he asks. “Where exactly on a mountain would you draw the line above which soil science no longer applies? Even if you could draw such a line, would it apply to all mountains in the world? I believe that by thinking about those questions, you can start to see how silly an arbitrary depth cutoff is.”

He argues a threshold needs to be based on science, not assumptions, and that he’s seen no convincing data that pedology suddenly stops making sense after a certain water depth. Studies need to take place to determine if such a depth exists, he says.

“We need to at least consider everything, if only to rule things out without making assumptions,” Wessel says. “I think that means we need to take things about 11,000 m deep, to the Challenger Deep, the deepest known part of the ocean.”

Many other soil scientists agree that the cutoff needs to be re-evaluated. SSSA Fellow Martin Rabenhorst, a professor of soil science at the University of Maryland and Wessel’s Ph.D. adviser, agrees with the case his former student is making and has begun to think about the challenges ahead for exploring deeper soils.

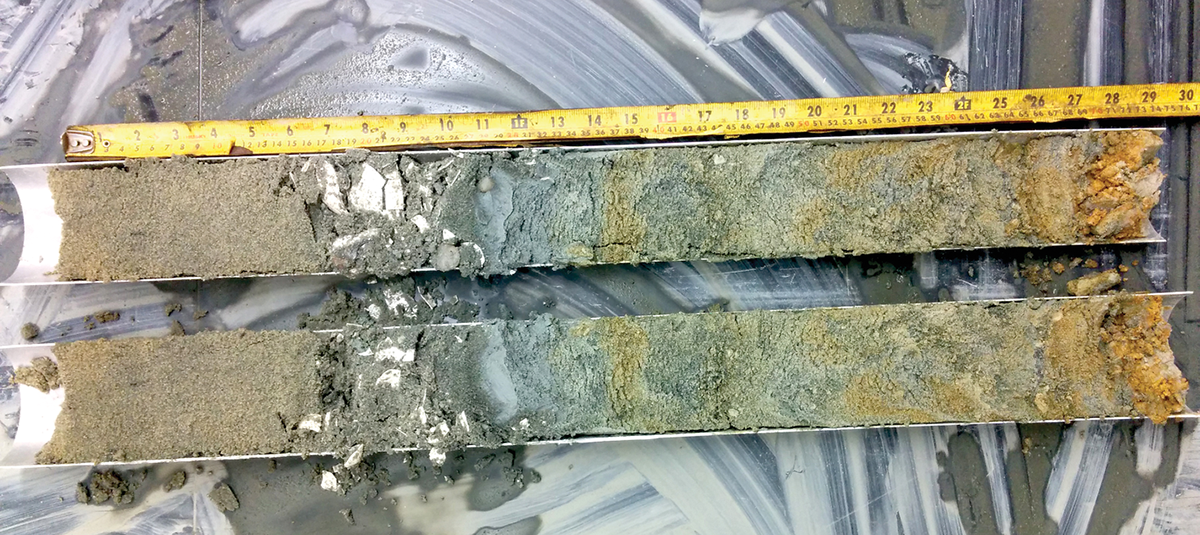

“I think it is much too shallow, and everyone I know that works in subaqueous systems also agrees that this is too shallow,” he says. “The depth to which you work underwater is dependent to some degree on the tools available. Using commonly available hand-type tools, like augers and corers, it’s pretty easy to go down to 5 or 6 m off the side of a boat. It gets challenging to go much deeper and often special equipment is necessary.”

Rabenhorst adds that the field of soil science will confront tough questions as pedological investigations move from shallow estuaries to the ocean bottom. Although there are those who doubt the relevance of pedology in deep-water soils, he says, the time and effort of many soil scientists has shown they are ready to make important contributions at deeper depths.

Wessel imagines an ocean full of collaborations among soil surveyors, academic soil scientists, extension professionals, and aquatic science experts. He even hopes for a future joint meeting of SSSA and an aquatic scientific society.

“As we continue to collaborate, we’ll push our work deeper and deeper, and perhaps one day a pedologist will make it all the way to the Challenger Deep,” he says. “There is still a lot to discover, and soil scientists can play a part in that discovery.”

Dig deeper

Cedric Evan Park, Barret M. Wessel, Martin C. Rabenhorst, Subaqueous pedology and soil‐landscape model evaluation in South River, Maryland, USA, Soil Science Society of America Journal, 10.1002/saj2.20520, (2023)

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.