Deep learning: The future of genomics-driven plant breeding?

Deep learning is a powerful subset of machine learning, a kind of artificial intelligence that relies on large datasets to make predictions. In a new special issue of The Plant Genome, researchers tackle the up-and-coming discipline of using machine-learning methods to enhance genomic prediction. One standout article outlines the awesome potential of deep learning to help plant breeders make better selections while giving us a glimpse into the challenges of putting the technique into practice.

Ever unlocked your phone with your face? Or used a speech-recognition tool like Siri or Alexa?

You’ve reaped the benefits of deep learning.

But for plant breeders, there’s a lot more to deep learning than searching the web with voice recognition. Deep learning is an artificial intelligence tool that uses artificial neural networks to make accurate predictions of unobserved cultivars based on a massive amount of data inputs. That means all the “omics” data are fair game, along with phenotyping data, environmental data, and the genomics of the breeding lines themselves. Breeders hope to use deep learning as a tool to improve plants more quickly, making accurate and powerful selections using these massive datasets.

Scientists from around the world contributed to a new special issue of The Plant Genome, highlighting the potential (and challenges) of using machine learning for plant breeding. Rajeev Varshney, Director of the Center for Crop and Food Innovation and International Chair in Agriculture & Food Security at the Food Futures Institute at Murdoch University in Australia, served as the guest editor of the issue. He points our gaze toward one article—“Deep-Learning Power and Perspectives for Genomic Selection”—and the possibilities that are already underway for using genomic selection to breed plants in a constantly changing world (https://doi.org/10.1002/tpg2.20122). Two study authors—Osval Antonio Montesinos-López and José Crossa—detail their findings and what we can (and can’t) expect deep learning to do.

What Is Deep Learning?

Deep learning is a subset of machine learning, which is itself a type of artificial intelligence (AI). Now, AI uses computers and data to solve problems and make decisions in a simulacrum of the human decision-making experience. In fact, IBM posits that ideally, AI won’t be like human decision-makers, but will be entirely rational.

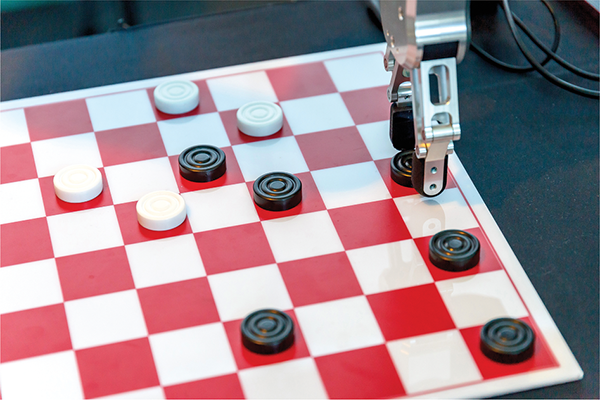

Machine learning refers to a system of algorithms that a human being trains to make insights and decisions. In fact, the term “machine learning” was coined by Arthur L. Samuel in 1959 during his experiments teaching a machine how to play checkers.

In checkers, each player can make a single decision per turn, creating a cascade of events leading to either victory or defeat. The machine learns which decisions are “right” or “wrong” based on the outcomes—if it moves a piece here, it loses it, so that move is incorrect. And it learns, building “memories” of which moves lead to which outcomes, predicting how one play leads to another, until, eventually, the algorithm becomes both knowledgeable and commonplace. It’s no more unusual to see someone playing checkers against a computer than it is to see a person sipping a venti latte in a big cardboard cup.

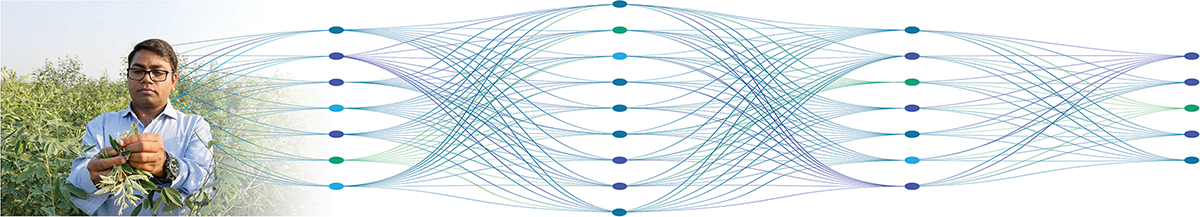

One layer deeper, deep learning is the most powerful tool yet. It tackles tasks with multiple inputs—things much more complex than a game of checkers.

“Deep learning methods are quite efficient for working with raw data without so much intervention from the user,” Osval Montesinos-López explains.

Montesinos-López—a professor of telematics at the University of Colima in Mexico—points to the biggest blessing of deep learning for plant breeding: it requires less pre-processing of inputs and deals with tremendous amounts of data. Deep learning uses stacked “layers” called “deep neural networks.” These layers interconnect both horizontally and vertically through computational units called nodes. These nodes exchange information with nodes in the same layer and with nodes in other layers, too.

Within a neural net, each node is “weighted”—that is, it will fire if an input reaches a certain threshold, passing a signal along to adjacent nodes within its layer and into deeper layers. At first, according to MIT, all the nodes in a neural network are randomly weighted. That is, they haven’t quite calibrated the proper weight of each input to fire. But as researchers train the neural network by feeding in massive quantities of data at its lowest layer, they can calibrate it by comparing the predicted outputs generated by the deep learning algorithm with known output data. Eventually, they’ll create a model deeply attuned to their specific inputs, poised to make the most accurate possible predictions given any set of inputs closely related to the datasets with which they were trained.

Deep Learning for Plant Breeding

When it comes to plant breeding, inputs can include a massive set of genomic data, from transcriptomics to phenomics, proteomics to metabolomics. With faster, cheaper sequencing abilities, researchers are gathering tremendous quantities of highly specific genomic data.

Take Rajeev Varshney and his collaborators at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) and other organizations around the world, for example. The team recently published a genetic variation map based on the sequences of 3,366 chickpea genomes in Nature (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04066-1). Chickpea is ripe for use in deep-learning methodologies.

“We sequenced over 3,000 lines and generated phenotypic data at six different locations for two years,” Varshney says. “With that depth of genome-sequencing data, we can identify that, out of these thousands of lines, this gene or combination of genes leads to disease—or to superior traits. We can validate our hypotheses in the field. We won’t have to plant out the remaining lines from the genebank to check—we can just sequence and predict their trait phenotype using data from those 3,000 lines.”

In fact, they are in the process of sequencing 10,000 total lines of chickpea. In the same vein, Varshney’s research team has detailed the whole-genome resequencing of 396 pigeonpea lines in a contribution to the special issue in TPG (https://doi.org/10.1002/tpg2.20125). The team used whole-genome resequencing to predict better lines to develop a new set of hybrids with higher yields. The study highlights how this method is a valuable tool for identifying single-nucleotide polymorphisms related to heterosis (in which hybrid individuals outperform both parents) in pigeonpea.

This is exactly the situation that scientists like Varshney, Crossa, and Montesinos-López see as ideal for machine-learning applications.

“The whole idea with machine learning is predicting the performance of lines or hybrids or cultivars in new conditions,” says Crossa, a Distinguished Scientist of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and a professor at the Graduate College in Mexico. Though the future is never certain, changing climatic conditions introduce even more uncertainty.

Piqued your interest? There are some things to keep in mind.

Practical Tips for Using Deep Learning

First, it takes someone with specialized knowledge to build a deep-learning algorithm. Montesinos-López contrasts this with traditional machine learning, in which you can create a hierarchy of traits manually, assigning some more or less importance. It’s both a strength and a drawback that deep learning requires less handholding on the part of the scientist operating it.

“It’s not easy to create a model,” Montesinos-López admits. “Many people look at deep learning like it’s a black box—you give it inputs, and you can get good predictions, but you cannot easily identify which factors were included to get that good prediction.”

But the knowledgeable researcher shouldn’t blindly trust the outputs since deep-learning algorithms can make mistakes, despite the massive quantities of information they synthesize. Instead, researchers serve as the critical eye, watching over the process and executing the final decision over the breeding process, using the deep-learning method for support.

“What’s fantastic about deep learning is the flexibility it offers to produce predictions for multiple traits with different kinds of responses and for multi-environment data,” Montesinos-López says. “But we still need to work on the interpretations of those results.”

A second limitation is the sheer amount of data a deep-learning algorithm requires to make accurate predictions. Plus, there’s the idea that there’s “no free lunch” when it comes to creating an algorithm—the predictive power of any single algorithm is only as good as the match between its training materials and the new inputs.

For plant breeders, this means that you can’t just take an algorithm calibrated for wheat breeding in Mexico, use it in India, and expect accurate predictions.

Instead, researchers can use “transfer learning” to take pretrained models and adapt them to new places. For smaller breeding programs, this might mean using an algorithm developed by a much larger project (like CIMMYT, for example) and using it as a “feature extractor.” A feature extractor is the technical term for determining the weights at which certain nodes fire throughout the multiple layers of a neural network when given certain inputs. It’s like skipping a few of the initial calibration steps but still fine-tuning it for your genomics, environment, and breeding goals.

Crossa, Montesinos-López, and their coauthors caution against using deep learning as a “panacea”—it should not be blindly adopted, particularly if the dataset you are using is both small and has linear patterns.

Finally, it’s important to note that machine learning will not make the skillsets of plant breeders obsolete.

“Machine learning maximizes the role of a plant breeder,” Crossa says. “You might think this avalanche of data from different sources diminishes the role of the breeder, but the breeder is the person there to clarify, to take in all this data, develop high quality phenotypic data in the field, and make wise final decisions.”

Machine learning in general is new tool to help with predictions in plant and animal breeding—one that looks to the future, to the growing omics disciplines for deeper structure, statistical backing, and streamlined selection. But it hasn’t moved beyond the grasp of history just yet. Even with deep learning, plant breeders (and future plant breeders) need a well-developed understanding of all the things that come into play. Rooted in history, a good breeder understands the fundamentals. But in the face of a swiftly changing climate, growing food insecurity, and increasing threats from pests and pathogens, there’s plenty of room to grow, too.

“Our philosophy is to break the internal mental structure we have, to see how we can do things with a very strong statistical and scientific bases, but just a bit differently,” Crossa says. “If we change the structure of our minds, the way we think about these things, we can solve some of the problems we face as plant breeders.”

Dig deeper

The Plant Genome special issue, “Advances in Genomic Selection and Application of Machine Learning in Genomic Prediction,” can be found online at https://bit.ly/3rRKzy7. In particular, the following articles may be of interest:

Rajeev Varshney’s introduction to the special issue: “Advances in Genomic Selection and Application of Machine Learning in Genomic Prediction for Crop Improvement”: https://doi.org/10.1002/tpg2.20178

“Deep-Learning Power and Perspectives for Genomic Selection”: https://doi.org/10.1002/tpg2.20122

“Characterization of Heterosis and Genomic Prediction-Based Establishment of Heterotic Patterns for Developing Better Hybrids in Pigeonpea”: https://doi.org/10.1002/tpg2.20125

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.