Tapping soil compaction’s secrets with seismic signatures

- Compaction is an “invisible” soil property that we typically characterize at limited spatial scales using soil core sampling or cone penetrometers.

- A new study in Vadose Zone Journal (VZJ) outlines a detailed framework for characterizing soil compaction with seismic signatures—a geophysical method that could provide field-scale instead of point measurements.

- The article is part of a new VZJ special section, titled “Agrogeophysics: Geophysics to Investigate Soil-Plant-Atmosphere Interactions and Support Agricultural Management.”

Soil compaction is an emerging threat to both agricultural and natural lands associated with modern mechanization. Compacted soil—whether near the surface or in the subsurface—can impede seedlings from emerging, increase surface runoff, modify the soil’s ability to hold water, and hinder root growth. Over time, soil compaction contributes to insidious and persistent yield losses.

“Soil compaction is one of those unobservable traits of soil structure,” says SSSA Fellow Dani Or. “You can look at aggregates and bulk density, but you can’t see how things are bound mechanically.’

What producers do see is yield losses, but by then, it’s incredibly difficult to reverse compaction below the soil surface and may take decades to rectify. Plus, the average tractor has increased from less than three tons in the 1940s to 10 tons or more today. Even with larger wheels, the pressure on the soil can contribute to subsurface compaction in the crop root zones.

Or, a soil and environmental physics professor at ETH Zurich, and his coauthors on a recent paper in Vadose Zone Journal (https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20140) set out to measure this invisible aspect of soil structure directly using a technique that has rarely been applied to agriculture: seismic waves. Their paper is a standout among submissions collected in a recent special section, “Agrogeophysics: Geophysics to Investigate Soil-Plant-Atmosphere Interactions and Support Agricultural Management” (available at https://bit.ly/3ykiYpa).

“Using geophysical techniques in agricultural lands has a lot of potential,” guest editor of the special section Sarah Garré says. “We’re at the perfect time to start using these techniques at a different scale to build a better, more sustainable agriculture.”

Garré, an SSSA member and researcher at the Flanders Research Institute for Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food (ILVO), pictures technologies like seismic monitoring as important steps forward in precision agriculture.

Here, first author Alejandro Romero-Ruiz and principal investigator Dani Or discuss the implications of using seismic technology to understand soil compaction at the field scale—and how it could help us be proactive about tackling compaction before we see yield losses.

The SSO

If you could time travel back to 2014 and stand in a little field just outside of Zürich, Switzerland, you’d see Or and his collaborator and coauthor (and fellow SSSA member), Thomas Keller, driving a monumental sugar beet harvester over a field. The team was intentionally causing massive amounts of soil compaction with the explicit goal of observing the soil’s recovery. That piece of land is known as the Soil Structure Observatory (SSO), generously provided by Switzerland’s Agroscope.

Since 2014, the team has been monitoring the compacted soil’s recovery using a variety of techniques. They planted vegetation on part of the field to see how native grasses impact soil structure while leaving other plots bare for comparison. They documented the field’s pre- and post-compaction state using measurements of infiltration, soil porosity, gas and water transport properties, crop yields, earthworm populations, and mechanical impedance—all of which they documented in a 2017 Vadose Zone Journal article (https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2016.11.0118).

“We really wanted to get a sense of the rates at which compacted soil recovers,” Or says. “When Alejandro [Romero-Ruiz] came along, we thought it was no longer enough to take core samples. We wanted a method to characterize soil structure, and that’s where the geophysical methods come in.”

Romero-Ruiz started his Ph.D. at the University of Lausanne in 2016 and successfully defended his dissertation in the spring of 2021. His doctoral work focused on a variety of geophysical methods like electrical conductivity and seismic sampling.

“Some of these methods have been used for decades for mineral and oil exploration or for military applications,” Romero-Ruiz says. “But we wanted to see if we could adapt them to understanding soil structure.”

Here’s the rub: to make a field-scale assessment of the mechanical properties of the soil, the team needed to first understand all the variables at play.

“We could have just done an empirical study, where we run an experiment, view the outcome, and learn something from it, but that’s not generalizable,” Or says. Instead, the team painstakingly created a model that takes the soil’s physical properties into account, from the soil constituents and their mechanical properties to the impact of water content, pore space, and suction. “The idea was to develop a framework that allows for generalization.”

And now things get technical.

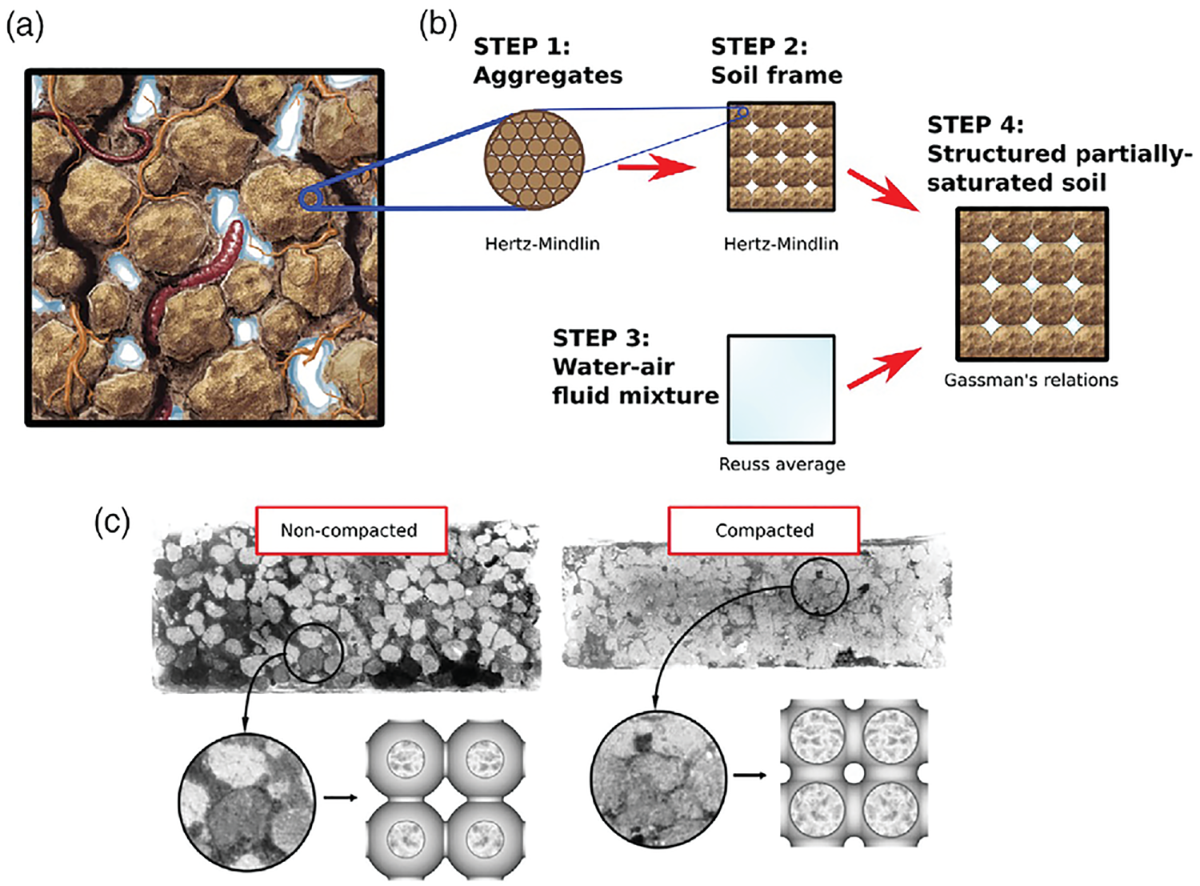

The model makes a few assumptions. It represents soil aggregates as little spheres with internal porosity and varying elastic properties depending on their makeup and wetness. The “soil” in the model is formed by considering a package of these little spheres, like looking through a picture frame at a cartoon handful of aggregates. For non-compacted soils, these little spheres have big gaps between them, which represent larger pore spaces. In compact soil, the team imagined the spheres squished together with less pore space. The decrease in pore space increases their mechanical contact areas, which changes how they transmit P-waves (compressional waves) through the soil. They also assumed that the entire pore space is occupied by a mixture of water and air. In their mathematical model, they considered the water–air mixture an effective fluid to better estimate how it impacts the speed of a P-wave.

Finally, the team identified key parameters in the model that are specific to the soil at the SSO as well as adjusting for treatment (with or without vegetation) and compactness (compacted and non-compacted). This allowed them to estimate how quickly P-waves move through the soil, explicitly considering soil compaction.

All of this was done to run predictions using the model to see how seismic signatures in the soil would vary based on compaction with soil wetness and type measured directly.

Model in hand, the researchers were ready to test their predictions in the field.

Seismic Signatures

The seismic setup was rigged up in the summer of 2019. To vastly oversimplify, the premise of seismic monitoring is kind of like smacking a mallet against the ground and listening to the impact through headphones.

So picture that, but much, much more precise.

An electromagnetic hammer was used as an impact source in the middle of a test plot with either bare compacted soil, compacted ley (a mixture of native grasses), or non-compacted ley. The impact source hammered the ground in precisely the same way every 15 minutes, sending seismic waves through the soil. Beside the impact source, a smattering of 18 geophones—small sensors buried near the soil surface—were poised to pick up the seismic waves. The geophones sent information from the ground to a seismometer hooked up to a laptop where the wavefields could be monitored, computing the speed of P-waves traveling through the topsoil.

But this wasn’t a test the team ran in a day. Instead, they left the seismic array in the field for two to four weeks per trial.

“We weren’t sure exactly how the hydrology would impact the signal, so we wanted to capture a period of time with a whole wetting and drying cycle,” Or explains.

Using soil moisture sensors, the seismic data was correlated with the wetness of the soil. The P-waves traveled more slowly through wet soil than through dry soil—a fact that was confirmed by leaving the array in the field during a rainfall event all the way through the soil drying.

With all this information, the team was able to see a “seismic signature” in the speed of wave propagation through the different soil plots. Because soil type was the same, they deduced that the differences in wave speeds were due to soil compaction. Their model neatly corresponded with the data they collected in the field—a definite bonus.

When they controlled for soil water content, the researchers found that the P-wave velocities in compacted ley were, on average, 31% higher than in non-compacted ley treatments and just 1.7% lower than compacted bare soil. Their findings indicate that the mechanical properties of compacted soil do, indeed, cause a distinct seismic signature compared with non-compacted soil.

“I was surprised that we didn’t observe a difference between the vegetated sites and the bare soil,” Romero-Ruiz says. Because there was little difference in compacted plots with and without vegetation, the team’s findings indicate that plants and their root systems had little effect in remediating soil compaction. Romero-Ruiz thinks one possible explanation is that roots just go deeper in the soil to avoid surface compaction.

Another possibility: the impacts of compaction are incredibly long lasting.

“By the time people take soil samples, measure bulk density, and see compaction, it’s already too late,” Or says. “Because you can’t see subsurface compaction, you might go over and over that soil with heavy machinery year after year, and you’ll be modifying the soil without ever knowing. It’s chronic and it’s not going away.”

Field-Scale Measurements

Compacted soil has a distinct seismic signature compared with non-compacted soil. But could seismic technology be a simple solution for farmers to understand compaction on the scale of an entire field? Could it look deeper, to subsurface compaction?

“The model we have so far is like a toy model, like a kid putting together a few Legos,” Or says. “We need people to put together more parameters that we missed—not just aggregates, but roots, soil samples with different properties.”

The model and the ground-truthing the team completed is a great start, but it’s a long way away from field-scale applications. Or pictures seismic signatures as a potential way to monitor compaction, not just in agricultural fields, but in natural lands, too, where it has major implications in plant growth, vegetation, and nutrient cycling that can all impact climate change.

Romero-Ruiz sees seismic monitoring as just one tool in an ever-growing toolkit of techniques that researchers and producers could combine to better understand the soil.

“It’s going to be challenging to develop this, to scale it up, but if we combine seismic signatures with other methods that are better established for soil science, we could get more detail,” Romero-Ruiz says. He anticipates researchers using seismic signatures in combination with electromagnetic methods to get a finer understanding of the soil subsurface at the field scale.

Altogether, the work collected in the new Agrogeophysics special section of Vadose Zone Journal highlights the multidisciplinary, diverse methods that soil scientists may use to better understand the soil.

“If we can understand what’s going on with compaction at wide scales, even at regional scales, that would really help us identify the things to change and provide farmers with incentives,” Garré says. “This is just the beginning.”

Dig Deeper

Check out Romero-Ruiz et al.’s study, “Seismic Signatures Reveal Persistence of Soil Compaction” here: https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20140.

Read the introduction to the Vadose Zone Journal (VZJ) Agrogeophysics special section, “Geophysics Conquering New Territories: The Rise of Agrogeophysics,” here: https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20115.

Read Keller et al.’s original description of the pre- and post-compaction soil structure at the SSO in this 2017 VZJ article, “Long-Term Soil Structure Observatory for Monitoring Post-Compaction Evolution of Soil Structure”: https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2016.11.0118.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.