Pushing perennial pyrethrum to flower in a single season

Increasing First-Year Yield Potential in a Plant with Important Organic Insecticide Applications

- Belying their cute, daisy-like exterior, the pyrethrum plant’s flowers produce potent insect-killing compounds called pyrethrins.

- A staple of organic agriculture, the perennial plant reaches its full yield potential the second year after planting, slowing production and return on investment for small-scale farmers and companies sourcing it for insecticides.

- New Crop Science findings detail how researchers at the University of Minnesota, partnering with the McLaughlin Gormley King Company (MGK), hastened flowering and pushed pyrethrum plants to produce a harvest in a single season.

The year is 1902, and three men—Alexander McLaughlin, John Gormley, and Samuel King—established the McLaughlin Gormley King Company (MGK), importing spices from all around the world to Minnesota for use in cooking, baking, and botanical drugs. But around 1910, the spice merchants noticed something odd: their shipments arrived in wooden crates with the spices packed in dried flowers that both cushioned them from damage and kept insects at bay.

By 1915, the company turned their attention to importing dried pyrethrum powder, made of the same

flowers they’d been seeing in their spice shipments. They knew that farmers had been using ground, dried pyrethrum flowers, mixed with water, to ward insects off their plants since the time of the ancient Egyptians. But could they create something standardized with more reliable performance?

In 1919, the company hired a USDA chemist named Dr. Charles Gnadinger, who was an expert in chemistry of extracts, specializing in vanilla. Before long, Gnadinger helped MGK create a pesticide from the isolates of the pyrethrum flower: pyrethrins. It was a breakthrough for the company—they had made an insecticide solution from a flower with a fabled history that would perform the same way no matter when it was purchased or manufactured.

Today, MGK produces organically compliant insecticides under the PyGanic family of products. Their pyrethrum-based insecticides serve as a crucial tool in organic farmers’ arsenals worldwide. The company sources their organically produced flowers primarily from growers in Tanzania. In the same spirit of innovation that brought Dr. Gnadinger to the team way back in 1919, MGK reached out to eminent chrysanthemum breeder and professor of horticulture at the University of Minnesota, Dr. Neil Anderson.

In 2012, Anderson, an ASA, CSSA, and SSSA member, teamed up with MGK, and their collaboration resulted in a recent, foundational paper exploring the genetic potential of the pyrethrum plant. New Crop Science research details how Anderson and his team put selection pressure on an enormous amount of different pyrethrum plants to drive flowering in one year, instead of two (https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.20453).

Growing Py

There are two species of pyrethrum that produce pyrethrin compounds (or py, for short): Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium and Chrysanthemum coccineum. The former produces flowers throughout the growing season or in flushes and is native to the mountains of Dalmatia bordering the Adriatic Sea, according to Gnadinger’s 1933 book on the plant. Chrysanthemum coccineum, on the other hand, does not flower throughout the growing season and is commonly known as painted daisy—it originated in the Middle East.

So it may come as no surprise that the ancient Persians were the first to use C. coccineum flowers as insecticides as early as 400 BC. Today, commercial production utilizes C. cinerariifolium since it produces flowers throughout the growing season, and those flowers have greater concentrations of pyrethrin compounds.

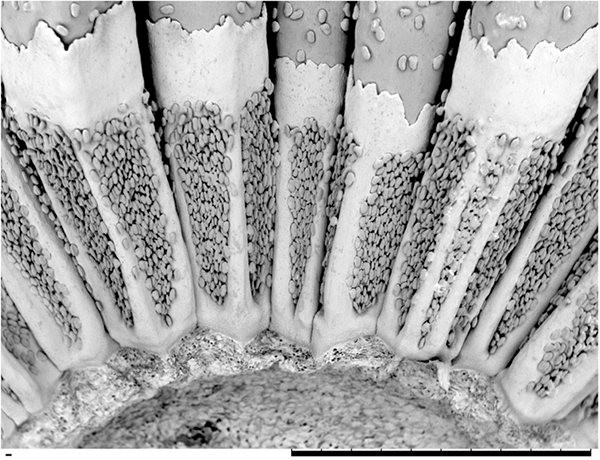

Pyrethrum plants produce pyrethrins in hairlike cells called trichomes. Though you can find trichomes all over its surface, the highest concentration is in the flower itself, producing 94% of a plant’s total pyrethrins.

Today, MGK sources the flowers they use in their organic “green pesticide”—the moniker given to pesticides produced from a plant, rather than through chemical synthesis—from small farms in Tanzania.

“There are pyrethrum fields there that are as small as my little office,” says Dr. Robert Suranyi, Research Leader in R&D at MGK and coauthor of the Crop Science study. “The average farm in Tanzania that grows pyrethrum is less than an acre, but growing py brings in a steady income for these farmers over the course of the season. It’s not just one harvest at the end—they are paid continuously as they harvest flowers.”

Suranyi described the growing process for farmers working with these plants. First, MGK and its subsidiary company, Pyrethrum Company of Tanzania (PCT), distribute high quality seeds to farmers, free of charge. Farmers produce seedlings in September, which they then transplant to production fields in December. By July, the plants produce a small number of flowers for harvest, but it’s nowhere near their full yield potential, which they reach in their second year of growth.

Farmers in Tanzania harvest flowers by hand every two weeks for about six months, increasing to every five days during peak bloom. They can leave a single pyrethrum plant in production for about three years before rotating the crop or starting over again. The goal of the Crop Science study was to see if flowering can create greater yield for farmers in that first year, greatly increasing their income and creating flexibility in their crop rotation.

Another researcher, Dr. Barbara Liedl, has trialed pyrethrum varieties for Anderson at her test fields at West Virginia State University (though she was not an author on the Crop Science study). Liedl is a professor of plant breeding and genetics, with a bustling greenhouse alongside the test fields.

“We’ve harvested as many as 300 flowers off one plant in a single week,” Liedl says. “I hate weeding, so we put down groundcovers—plastic—between the rows, and we don’t give them much excess attention or water, once they’re established. It’s shocking how well these plants do with benign neglect.”

Using Pyrethrins

From a pest management perspective, pyrethrin compounds work rapidly on contact to paralyze insects. For organic growers seeking green pesticides, another advantage is that pyrethrins degrade in just a few hours, depending on environmental conditions. They also effect a broad range of insects and have low mammalian toxicity.

Liedl, who runs an organically compliant greenhouse in her program, relays the benefits of using pyrethrin compounds in her pest management system.

“Beneficials are our biggest biological controls in the greenhouse,” Liedl says. “For us, it’s cheaper to ship in insects every week when we’re working with produce—tomatoes, lettuce, things you’re going to eat—than to get chemistries and spray. But pyrethrin has a low re-entry period that I really like.

You can go back in just four hours after you spray because you know it has degraded.”

Pyrethrins, though, have to come into direct contact with insects to affect them. According to Suranyi, it defines what you need to do to make it work in your integrated pest management plan.

“You have to get good coverage—you have to make contact with the target insect to control it. The application technology you use is critically important to get thorough coverage. So if you have a plant with a dense canopy or insects on the undersides of the leaves, like soybean aphids, it requires some special attention to get the necessary contact for activity,” Suranyi explains. “Merging our understanding of the ecology of the target pest with the appropriate application technology determines the performance of pyrethrins.”

Pyrethrin-based insecticides are in demand with organic producers. Though pyrethrins served as the template for another common class of insecticides called pyrethroids, pyrethroids are synthetically produced. They don’t carry the moniker “green pesticide” and are not allowed for use by producers using organic production.

With all that in mind, the team tackled a big question: how do you take a second-year flowering perennial and get blooms in the first growing season?

Finding Early Risers

“The big thing is you don’t have to wait for it to go through a cold period before it blooms, and you can get flowers in one year instead of two,” Anderson says. “We’ve done this before with crops that produce bulbs or corms—the geophytes—where going from seed to flower takes about five years. It took me and my project 20 years of selection, but now we have gladiolus that go from seed to flower in two to four months.”

Anderson’s experience in “annualizing” perennials provided him with the means to push pyrethrum to flower in a single year. He used two primary methods: hot, long days and persistent selection for early germination and early flowering.

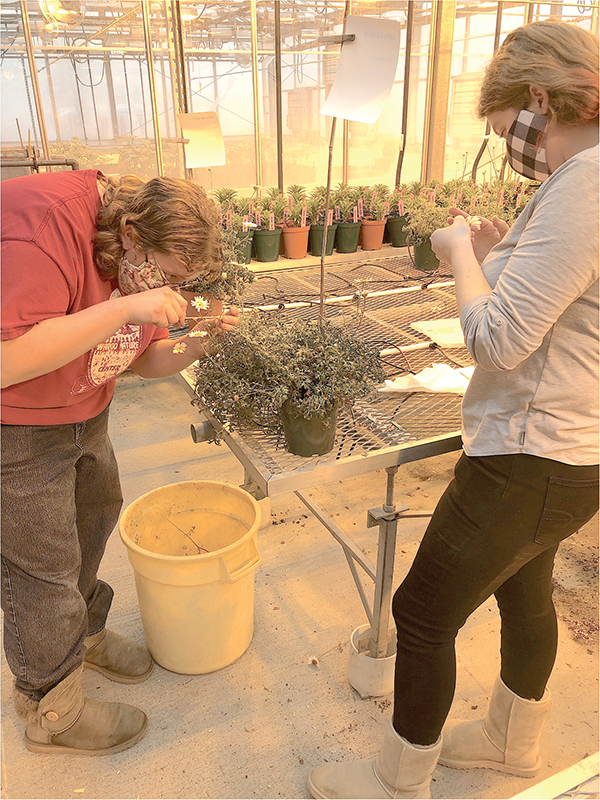

To tackle this ambitious goal, they needed to take stock. Anderson and his dedicated team of student assistants started working in the University of Minnesota greenhouses to screen a wide array of germplasm from seven different seed lots supplied by MGK. The oldest seed lot hailed from a harvest in 2000, and another notable bunch was open-pollinated from wild populations in Croatia.

“It’s amazing what you find kicking around in seed vaults; the stuff people collected and then stopped breeding, or they died, and you inherit it,” Anderson says. “There’s always remnant seed hanging about.”

First, Anderson and his team pre-tested germination rates with 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TZ). Testing with TZ is a quick way to see if your seeds are viable—the TZ stains living cells as they respire during germination while dead cells remain colorless.

Next, soil and lab germination rates were tested, and seed germination was found to be highest in Weeks 2 and 3 after sowing.

Plug trays—something typically seen in horticulture operations—were then used to undertake seedling selection on a massive scale.

“Typically pyrethrum would be sown on flats,” Anderson explains, “but the plug trays—10 by 20 inches—are like a little acre, almost. You can grow 50 plants, or you can grow 512, all on one little test plot. Then you exercise selection.”

Anderson uses a method he calls “toothpicking,” in which he color-codes his seedlings by germination date. That is, all the seeds that germinate in the first week after sowing get a green toothpick, for example. Second-week seeds are red, third week blue, fourth week yellow, and so on.

“It’s like a work of art—thousands and thousands of seedlings, and you can just look and see when they germinated,” Suranyi says. “It’s a really elegant way to make selections.”

Plus, the toothpicking method makes it easier for the team to manage data. With many thousands of plants from multiple seed lots and various germination times, the color-coordinated system makes it a breeze to quickly pick out the early germinators when, by Week 23, the late risers might have caught up.

After toothpicking, the team started “rapid generation cycling,” in which they exposed the little plants to conditions that encourage flowering without ever giving them a rest. Pyrethrum typically spends its first year establishing itself and then requires cold exposure before flowering in its second year. Here, early germination was used—along with accelerated growth and high leaf-unfolding rates—as an indicator for selecting plants with the potential to flower in one season.

The team transplanted 5,000 of the top 50% speediest germinators per seed lot, with preference to seedlings that germinated in Week 1. They moved the seeds from plug trays into roomier cells.

Eventually, 21 weeks after sowing, 1,000 to 1,800 seeds per lot were transplanted into larger containers with just one plant per container. At this point, the researchers were looking for the healthiest plants, resistant to root rot and thrips, with lots of vigor and potential for flowering.

This whole time, they kept the plants under greenhouse conditions with 16 hours of light per day, but at Week 37, Anderson turned up the heat. The temperature shifted upward, from 24.4 to 25.6°C in the day and from 18.3 to 22.2°C at night. Plus, they more than tripled the light intensity for the plants.

By Week 43, they had flowers.

Next Steps

“We didn’t expect to make progress this fast—we had no idea we could get them to reach visible flowering and bud date so quickly, and it’s something no one has ever done before,” Anderson says.

The team has plans to improve pyrethrum plants for lots of other traits. Anderson elaborates on some of their targets.

“We’re selecting for winter hardiness, perenniality, plant shape, regrowth potential, yield potential during the growing season, and, of course, high py concentration!”

Circling back to Tanzania, where MGK sources its hand-picked pyrethrum flowers for its green pesticides, farming employs a huge number of people. According to The World Factbook, 67% of the labor force in Tanzania is employed in agriculture, which makes up about a quarter of the nation’s gross domestic product.

In short, there’s demand for py as a cash crop in developing countries, where it serves as a welcome source of income for farming operations. Creating an annualized perennial version of the pyrethrum plant would provide farmers a return on their investment within a single year. It helps the farmers increase flexibility in their crop rotations and maximizes the value of their investment of time and money in the crop by shortening how long they must wait to harvest high yields. In turn, it helps companies like MGK more effectively manage supplies to meet the demands of consumers worldwide.

“Growing pyrethrum provides a low-input crop option to thousands of farming families in Tanzania,” Suranyi says. “To me, pyrethrum is a powerful example of the wide-ranging connections between farmers across the world. Growing pyrethrum sustains thousands of farming families in Tanzania, which then supports the production of organic crops worldwide.”

Dig Deeper

Check out the Crop Science article, “Rapid Generation Cycling Transforms Pyrethrum (Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium) into an Annualized Perennial,” at https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.20453.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.