Finding the gaps in crop wild relative conservation

New Analysis Shows Urgent Need for Increased Conservation

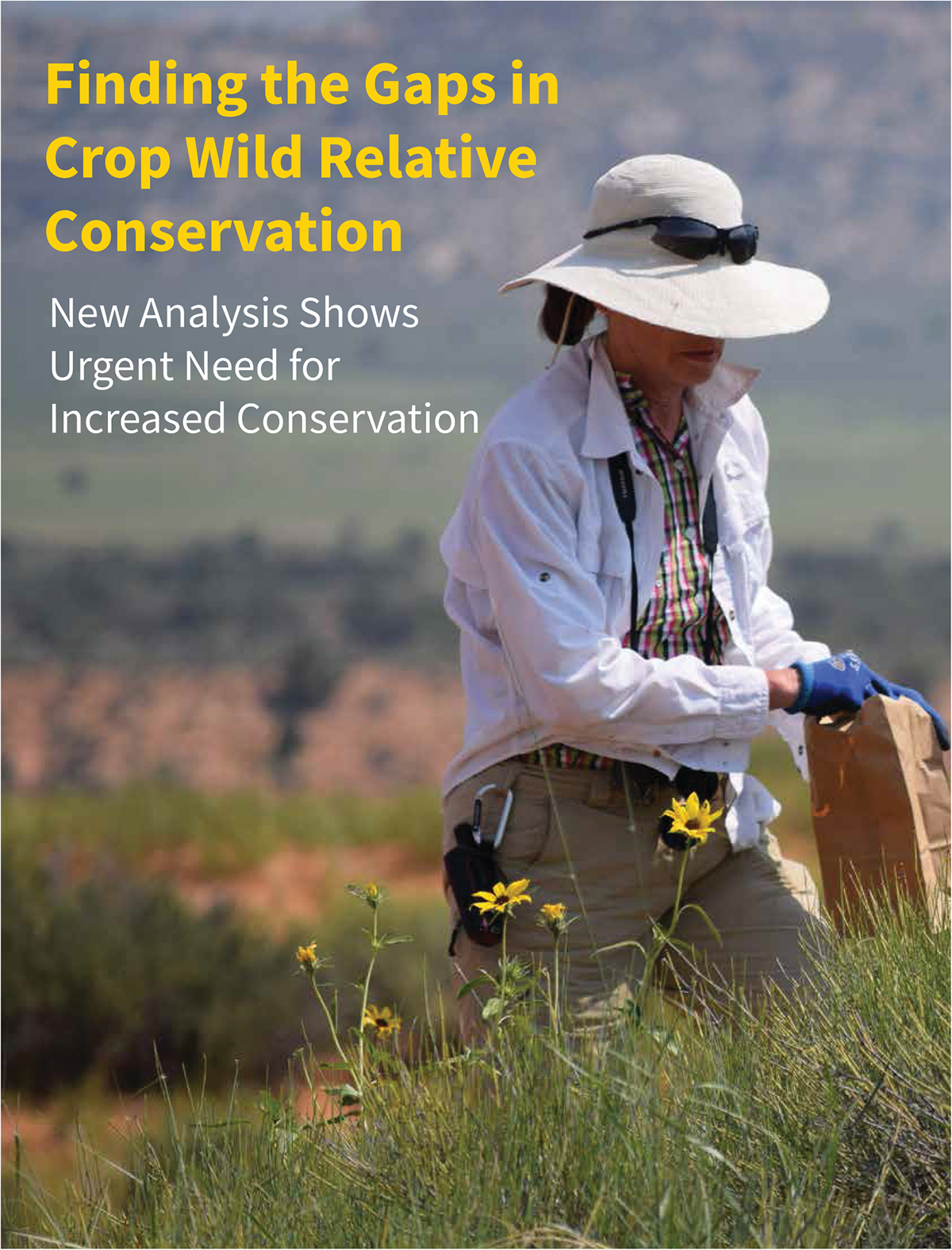

- The U.S. native wild relatives of globally important crops include sunflower, raspberry, ovifera squash, pecans, blueberries, and cranberries, among others—they serve as key sources of genetic diversity for domesticated crops and as ecological and cultural resources in their own right.

- Researchers compiled data on 600 native taxa to understand their conservation status both in germplasm collections and habitats.

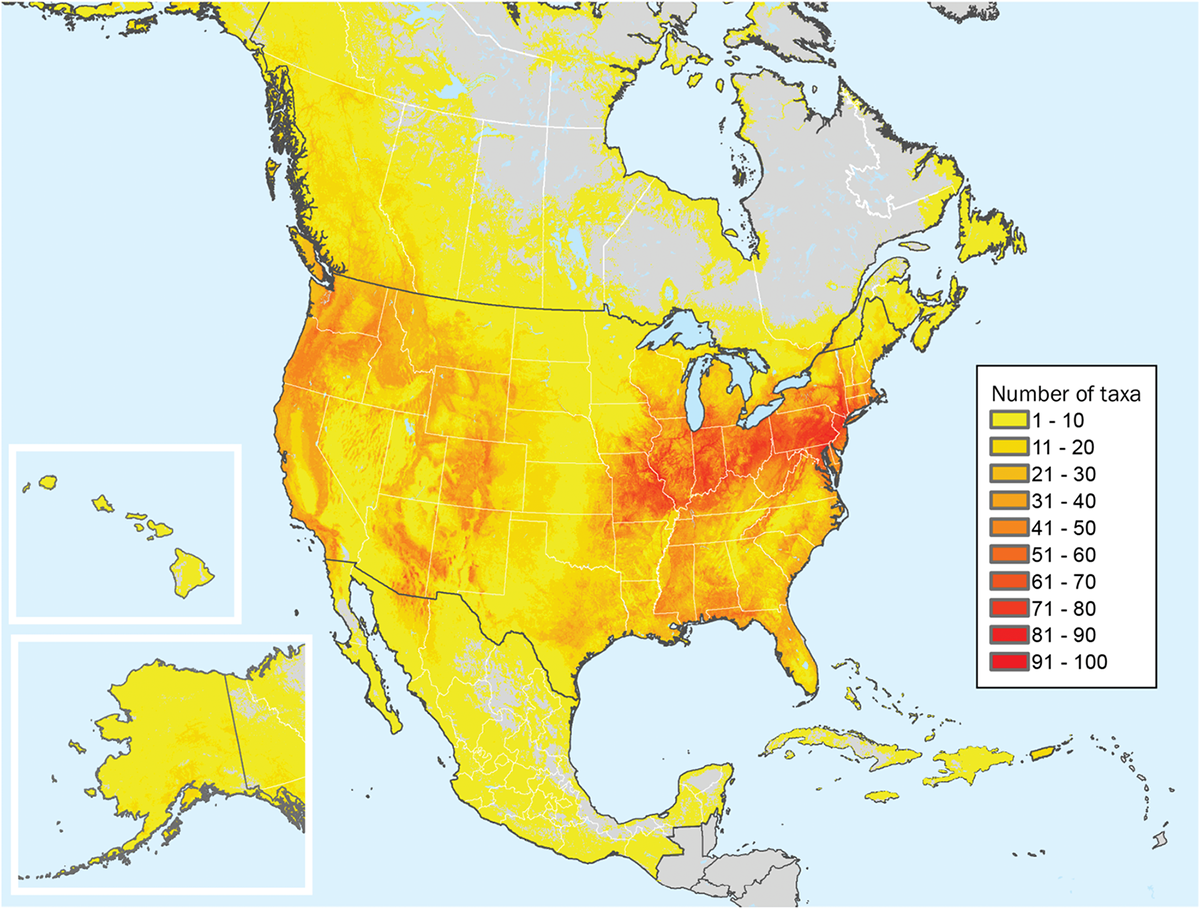

- Their intensive search created maps that will help us understand where we can find crop wild relatives, given that 93% of these plants have urgent gaps in ex situ collections and a similar proportion have significant habitat conservation needs.

Pests, diseases, and the pressures of a changing climate push our crops to their limits; they need constant improvement to keep up. Crop wild relatives (CWR) can help.

Closely related to domesticated crops, CWRs are wild plants that serve as critical sources of genetic diversity for plant breeders seeking to improve the resiliency and productivity of their domesticated cousins. In many cases, these plants are also important cultural and natural resources.

However, understanding how well we’ve conserved these plants—in gene banks and botanical gardens as well as in their natural habitats—takes some serious effort.

“We’ve been trying to understand how much crop diversity is conserved in seed banks and wild places for about 50 years, originating with people like Jack Harlan,” says Colin Khoury, a researcher at Saint Louis University, the National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation (NLGRP) of the USDA-ARS, and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT). “These people were in the field all the time; they just had a feeling for what was out there. But now, with so many threats to wild plants, we’re concerned about a much larger number of species. How can we prioritize our efforts?”

The answer: a gap analysis.

After 10 years of intensive data collection and modeling, authors of a new paper in PNAS outline the conservation status of more than 600 taxa of CWR (https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2007029117). This gap analysis is a key step in helping us understand the locations where we might find CWR and which areas would be great candidates for conservation efforts. It’s also an important contribution to the road map for their protection and use in the region (https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2019.05.0309).

Here, we talked with coauthors Khoury, Karen Williams, and Stephanie Greene. Williams is a botanist with the National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, USDA-ARS, and Greene is a curator at NLGRP. They explain why the gap analysis is so critical for strategic interventions to conserve the “cultural-genetic-natural resources” that are U.S.-native CWR.

On the Hunt

Before you can find gaps, you have to figure out what you’re looking for. Way back in 2013, Khoury and Greene were among the authors of an award-winning paper in Crop Science that took inventory of CWR and other useful wild plants in the United States (https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2012.10.0585).

This study detailed more than 4,500 taxa, of which 2,500 were CWR. The U.S. is home to the CWR of a wide range of food, fiber, medicinal, and industrial crops.

The authors highlighted taxa related to major agricultural crops, including wheat, onion, sunflower, strawberry, sweet potato, blueberry, cranberry, and chile pepper, just to name a few. Top-priority taxa also included iconic foods like sugar maple, wild rice, and American chestnut—plants that are important in regional and traditional diets, if not as mainstream agronomic crops.

“The inventory was our first big milestone,” Khoury says. “Before you can make a model, you have to decide what you’re going to focus on, and we focused on the wild relatives that are really likely to be used by plant breeders.”

The inventory served as the cornerstone for the gap analysis.

Finding the Gaps

List in hand, the team set out on the painstaking task of evaluating the conservation status of 600 different taxa, starting with native occurrence information and ex situ records.

These data came from online databases like PlantSearch, the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, and GRIN-Global. Their search revealed where plants occur in their natural habitats, at least historically.

The authors combined these occurrence points with climatic and topographic information to predict the native range of each taxon.

“Modeling allows us to make maps that show the general distribution of the species using point data based on where we’ve collected them in the wild,” Greene says. “When you bring in other characteristics like environmental variables, then we can predict this envelope on the landscape that has the sort of conditions where we’d expect these species to actually exist.”

Native ranges can also point the team toward specific collection sites that aren’t currently represented in conservation repositories, including for certain characteristics like drought or cold tolerance. By collecting in areas where these conditions are likely to occur, they can get a broader range of genetic diversity for use in plant breeding.

To find the gaps, researchers compared their modeled ranges against the sites where samples had already been taken. Locations not yet sampled represent gaps in current ex situ conservation. They found major ex situ conservation gaps for 93.3% of all CWR, including 83 taxa completely absent from conservation repositories.

Then the team added another layer: in situ conservation. Is the plant conserved in its natural habitat through habitat preservation?

The researchers scored for in situ conservation using the representation of taxon ranges within locations listed in the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA). This includes national parks, wilderness areas, and many other open-space conservation categories.

Combining in situ and ex situ conservation analysis, the team assigned each CWR a current conservation score. Shockingly, they categorized 58.8% of all taxa as in urgent need of further conservation action based on these combined in situ and ex situ assessments.

Finally, putting all these conservation maps together helped the group identify taxonomic richness hotspots—locations where the ranges of multiple CWR species overlap.

“Hotspots can be very useful both for collections and for in situ conservation,” says Williams, who directs the USDA program for collection expeditions across the United States and in other countries. “Not only can we sometimes collect multiple CWR on one expedition, we can prioritize these areas for conservation.”

The study provides an intense and eye-opening report of what we’re missing, making it easier to prioritize which species we need to collect now and how to direct further conservation efforts. It’s all about being strategic to maximize limited resources and protect the CWR most in need.

Conservation Action

Conservation efforts for native CWR are already well underway both in situ and ex situ.

In the wild, the Wild Chile Botanical Area in the Tumacacori Highlands of southern Arizona stands as one of the few national preserves dedicated to protecting a crop wild relative—the chiltepin pepper (Capsicum annuum var. glabriusculum). The Cranberry Glades Botanical Area in the Monongahela National Forest in West Virginia and the Cranberry Bog Botanical Area in the Olympic National Forest in Washington are examples of other preserves dedicated to CWR. Their success hints at the potential of the modeling created by Khoury, Greene, Williams, and their collaborators. The hotspots identified in the modeling provide strong foundations for choosing other areas to set aside.

“This gap analysis provides basic knowledge for land management agencies that are responsible for setting up natural reserves for CWR—like the BLM and the U.S. Forest Service. I hope it provides them the information they need to secure these materials in the landscape,” Greene says.

Meanwhile, new projects are underway that partner the boots-on-the-ground power of the U.S. Forest Service to support conservation of CWR with the capacity of the USDA-ARS and other institutions to conserve these resources in ex situ collections. Williams and other ARS members collaborated with the U.S. Forest Service to create a framework for this partnership. In fact, Williams completed one project so far that studied 45 populations of wild cranberries in National Forests across the country for consideration as in situ preserves for CWR. Williams was part of a team that published preliminary findings on the breadth of genetic diversity in cranberries in a recent Plants article (https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9111446).

“We’ve limited our work so far to conservation of CWR on National Forests,” Williams says. “We hope that collaboration can be extended to other land management entities in the U.S.”

A central purpose of the gap analysis is to guide strategic decision making for plants that are often out of the spotlight. Partnerships between land management agencies are a great start, but another critical step is bringing the project to the public. One way to increase education is through the help of botanic gardens in the U.S., which receive more than 120 million visitors in an average year.

“Based on current conservation activity, it would take perhaps 50 years to get everything done based on the information we generated,” Khoury says. “We really need to generate momentum, more collaborations, more resources, and in five years, accomplish the conservation activities that will protect these plants for the future.”

Pioneers in CWR research and conservation, like Jack Harlan, would be proud to see the progress enabled by database searches and modeling. With the dedication of this research team, we have everything we need to conserve these important cultural-genetic-natural resources, from sunflower to wild grape, cranberry to chile pepper.

Dig Deeper

Want to learn more about crop wild relatives? Check out these resources:

Crop Science Special Sections

- Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change: A Walk on the Wild Side, 2021: https://bit.ly/3bog7D3

- Crop Wild Relatives, 2020: https://bit.ly/3eGYtwv

- Celebrating Crop Diversity: Connecting Agriculture, Public Gardens, and Science: https://bit.ly/2RhUeOR

Podcast

- Crop Wild Relatives Week with Dr. Stephanie Greene: https://bit.ly/3y4ML6v

CSSA Website

- CSSA’s Crop Wild Relative Week page: www.crops.org/crop-wild-relative

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.