Fungal endophytes: An inside fix for abiotic stress?

- Some plants thrive in inhospitable places, and it’s not a matter of sheer adaptation—it turns out the fungal endophytes living within their tissues are the key.

- Rusty Rodriguez, CEO of Adaptive Symbiotic Technologies, discussed the journey of discovery that led to the development of their commercial fungal endophyte inoculant to help crops tolerate abiotic stresses.

- The research and discoveries pushed by Rodriguez and his colleagues are a step forward in harnessing the microbiome to benefit plant health and improve our food security.

So far, there is no smoking gun.

The team at Adaptive Symbiotic Technologies—or anyone else, for that matter—isn’t sure exactly how fungal endophytes help plants tolerate abiotic stresses like cold, heat, drought, damp, or sodic soils, but they do. These special fungi live within a plant’s tissues, engaging in a mutualistic relationship that benefits both organisms under tough conditions. Harnessing the power of this relationship might be a key movement forward in the fight to help plants overcome the stresses of a changing climate and improve our food security.

Rusty Rodriguez, CEO of Adaptive Symbiotic Technologies, spoke at the 2020 Virtual Annual Meeting of ASA, CSSA, and SSSA about the process of discovery behind the company’s recently commercialized fungal inoculant, BioEnsure. The inoculant is the product of about 30 years of microbiological expertise, 10 years of testing inoculants on more than 25 different crops planted over 2.9 million acres in 15 different countries, and all sorts of abiotic stress.

Now, Adaptive Symbiotic Technologies is scaling up, providing their products to distributors and getting feedback from real users. They’ve also shown what the endophytes can do for smallholder subsistence farmers in India where drought conditions negatively impact yields.

Here, we’ll tackle the big questions. What exactly are these endophytes? How did the team find out about them? And how can they help us grow plants under increasingly stressful conditions?

The story starts in Yellowstone.

Tropical Panic Grass and Friends

The soil surrounding the geothermal vents in Yellowstone National Park never freezes. Temperatures in the top layers of soil range from 20°C in the winter to 65°C in the summer.

Near the vents, tropical panic grass (Dichanthelium lanuginosum) thrives, developing biomass year-round. The geothermal soils steam as the surrounding cooler ring of earth is covered in snow; yet panic grass happily grows. In the mid- to late 1990s, Rodriguez and Regina Redman, now Adaptive Symbiotic Technologies’ Chief Scientific Officer, were part of a group of researchers interested in fungal endophytes and their relationship with plants in the natural environment. They hiked out to areas that ought to be hostile to life—salt marshes, deserts, fields of oily tailings left behind by mining operations—and looked for plants that grew despite the challenges.

Though there are multiple species that grow in Yellowstone’s geothermal soils, tropical panic grass was a breakthrough. The team collected samples, took them back to the lab, laid out the roots and shoots of the grass on fungi-friendly medium, and waited.

“We were lucky enough to be able to tease the system apart,” Rodriguez says.

Lucky?

“When you’re working with fungal endophytes, it’s a whole different game. It’s not like culturing bacteria or growing plants,” Kristin Trippe says. “You’ve got to have magic lab hands.”

Trippe, a microbiologist for USDA-ARS, organized the Annual Meeting symposium at which Rodriguez spoke. She’s watched as Rodriguez and Redman have made advances in fungal endophyte research over the years and was delighted to invite Rodriguez to speak at the meeting.

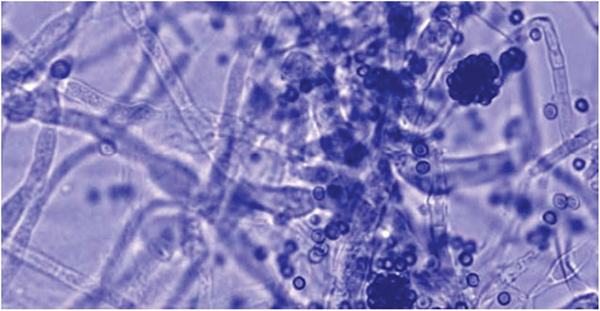

With their magic lab hands, Rodriguez, Redman, and their team of researchers cultivated both the plant and the fungus independently. They grew panic grass without its symbiont and cultured Curvularia protuberata, the fungus that emerged from the roots of the panic grass, all on its own.

Now, with control over the system, the team put the organisms to the test. In a 2002 study published in Science, the researchers detail their findings after exposing the organisms to varying heat conditions in the lab and the field (https://bit.ly/3znTrNz).

In the lab, panic grass inoculated with C. protuberata stood up to rhizosphere temperatures as intense as 65°C for 8 hours a day, 10 days in a row. The fungi-free plants died. Fungi exposed to heat, sans plant host, were unable to grow mycelium, germinate spores, or even survive temperatures greater than 40°C.

Inside the plants, the researchers were certain that the entangled organisms engaged in a delicate intercellular game of give and take. The fungi conferred heat tolerance to the plant, while benefitting from the plant’s increased stress tolerance. Neither plant nor fungi can take the heat alone.

But the field study is where things get interesting. The team went back to Yellowstone and backpacked out a thousand pounds of soil, Rodriguez explains. They pasteurized the soil, lugged it back into the park, and set up bottomless plastic tubs on a temperature gradient in the geothermal zone, planting inoculated and fungi-free tropical panic grass within the confines of the tubs separated by dividers. They left the plants there for a year.

When they returned, they found the uninoculated plants dead in areas where soil temperatures reached 35–40°C. The inoculated plants not only survived but grew—they developed roots and biomass.

“The moment we hiked back in and I saw that was when I knew we might be able to use this to mitigate the impacts of climate change in natural ecosystems,” Rodriguez says. “But we just couldn’t gain traction in that arena—it was too new, people thought it was snake oil. But Regina Redman, my wife and colleague, she started working with ag[ricultural] commodity groups that fund research. They funded her to see if this endophyte technology could be developed. That’s how we got started.”

Testing Fungal Inoculants

Since the experiments in Yellowstone, Redman and Rodriguez have made immense progress. Not only did they “tease apart” the panic grass system, but they’ve managed to show that fungal endophytes can benefit plants from highly divergent lineages, as well.

They took C. protuberata from tropical panic grass, a monocot, and managed to inoculate watermelon seedlings—a eudicot. They found that the endophyte conferred similar stress tolerance benefits in a massively different species of plant.

“That just tells us this communication, this relationship between fungi and plants, is highly conserved,” Rodriguez explains. “Monocots and eudicots diverged 130 to 200 million years ago. But it’s a microbial planet, and life had to figure out how to work with these guys or wall them off.”

Speaking of walls…the team hit one. Though Redman, Rodriguez, and their colleagues were making strides with C. protuberata in monocots and eudicots, another company had licensed the species, and the team had to change tack.

Their new goal was to find a fungal endophyte that would meet their specifications—35, to be exact—for inoculating crops.

In a 2021 Microorganisms study, the team details the process of isolating and testing fungi they found in two bunchgrass species growing in the highly saline soils of arid California, USA (https://bit.ly/3pPpzFE).

Their fungus of choice, Trichoderma harzianum, isn’t new to agricultural use. There are several products that use this fungus as a biopesticide to suppress disease-causing pathogens like Botrytis, Fusarium, and Penicillium sp. in products like Rootshield and Trianum-P. One major difference: these strains of T. harzianum live outside of the plant while Rodriguez and Redman are tailoring their product to live endophytically, helping the plant from inside.

From their bunchgrass isolates, the scientists grew fungal cultures on media, harvested conidia (the asexually produced spores on the tip of specialized hyphae) and irradiated them to drive new mutations. They then grew new strains up and tested them against lethal levels of fungicides to find strains that would hold up during seed treatments or in-furrow application.

After all this work, three strains made the cut. They took the fun to the field. They grew inoculated plants to test the fungi for biopesticidal activity and soil competitiveness to make sure their end product did not harm the plants or the soil. They also tested inoculated barley, rice, and soybean in test plots with historical disease incidence managed by faculty at Michigan State University, Texas A&M, and Oregon State University. The fungi did not confer tolerance to crops faced with biotic stresses.

For example, the trial at Michigan State University tested soybeans inoculated with the fungi blend for resilience in the face of soybean sudden death syndrome (SDS). The inoculated plants showed no statistically significant difference in SDS tolerance when compared with control plants in irrigated trials.

“I have a colleague that jokes about people wanting the answer in a jug,” Martin Chilvers, associate professor at Michigan State University and coauthor on the Microorganisms study, says. “But it’s always more complex than that. Rusty and Regina show a lot of instances where [BioEnsure] is definitely beneficial, but there might be other areas where you don’t see a return on investment. It’s really important for farmers to make sure a product works for their own unique conditions.”

So, BioEnsure isn’t a silver bullet; it won’t fend off pathogens or disease. But do BioEnsure’s unique strains of T. harzianum ever make their way out of the plant? After all, most strains of Trichoderma live their lives outside the plant, not inside.

To test this question, the team sampled soil before planting seeds and then took soil samples from the base of the plant two weeks, four months, and one year after planting. Soil microbes were analyzed by culturing samples on two different types of media. The first was a non-selection fungal growth media, which is a nice growing environment for pretty much all culturable fungal species. The second was fungal selection media containing chemical fungicides on which only BioEnsure’s unique strains of T. harzianum can grow.

The team found Trichoderma and other fungi in the soil samples for all time points when analyzed on non-selection media. But when they looked at selection media, they found Trichoderma in samples from pre-planting through four months post-harvest. For later samples, the team found no Trichoderma emerging from plants sampled four months to one year after harvest. It seems that BioEnsure strains die off along with the plant they inhabit.

Without fungicides, the team found both Trichoderma and other fungi in the soil pre-planting all the way through four months post-harvest. They found no Trichoderma emerging from roots and crowns of plants sampled four months to one year after harvest, again indicating that BioEnsure strains die off along with the plant they inhabit.

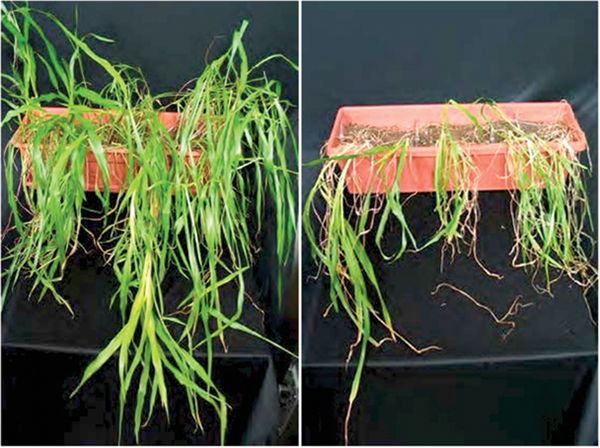

When pitted against abiotic stresses, though, BioEnsure shines. In all manner of agronomic crops, from barley to mung bean and from corn to cotton, when plants face increased heat, drought, and salinity stress, they benefit when the fungal endophyte is present.

Rodriguez’s presentation at the Annual Meeting highlighted an average yield increase of 26% and a “win rate” of 93.3% in corn treated with BioEnsure when exposed to water and/or heat stress under 15 different field-scale trials. That is, 93.3% of the corn fields treated with BioEnsure showed a 5% or greater increase in yield compared with untreated controls. For cotton, treated crops averaged an 18% increase in yield compared with untreated controls under water and heat stress.

Let’s now turn to one particular place where fungal endophytes have already made a huge difference: smallholder farms in Rajasthan, India.

Rajasthan’s Smallholders: A Case Study

The Indian state of Rajasthan is plagued by drought and intense heat. Farmers rely entirely on monsoon rains to grow their crops, but the monsoon season falls short nearly one in four years, devastating farmers who rely on their crops for subsistence, animal feed, seed, and income.

In 2014, Adaptive Symbiotic Technologies received a grant through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to further develop BioEnsure. The team had connections with Rajasthan—the perfect place to see how the abiotic-stress-fighting capabilities of their fungal endophytes play out. Through a program called Securing Water for Food (SWFF), the team took BioEnsure to 400 smallholder farmers, supplying them with seed treatments in 2016 and 2017.

The farmers rely on two staple crops: pearl millet (a monocot) and mung bean (a eudicot). Among a sample of 50 BioEnsure users interviewed by SWFF, the average farm size was 5.42 ha with 40% of interviewees relying on farming as their primary source of income for an average family size of 7.5 members. The growing season routinely reaches temperatures about 37°C, and 47 of the 50 users reported that changes in temperature and rainfall in recent years have negatively impacted their crop yields.

As Redman, Rodriguez, and their colleagues reported in the 2021 Microorganisms study, the endophyte treatment increased yields of pearl millet by 29% and mung bean by 52% compared with yields from untreated carryover seed.

“The majority of these smallholder farmers use carryover seed, and they just pick the coolest part of their non-air-conditioned homes to store it,” Rodriguez explains. “Their carryover seed has low germination rates and nowhere near the same yield as fresh-market seed, but fresh-market seed is eight times the price.”

For smallholders, endophyte treatments could be one way to help them increase yield in carryover seed while combatting the negative impacts of low rainfall and incredible heat stress. With no additional inputs beyond BioEnsure inoculation, their crops fared much better than untreated carryover seed alone.

The Adaptive Symbiotic Technologies team plans to return to Rajasthan and implement the next phase of their USAID grant: creating distribution networks to get BioEnsure to more farmers in the region. Plus, their plan has a female empowerment component. They want to train women as seed treaters, helping them start their own businesses.

Scaling Up

Redman and Rodriguez have scaled up since those early days in Yellowstone. Since Adaptive Symbiotic Technology’s founding in 2008, the company expanded in 2013 to a total roster of between 16 and 25 employees. They commercialized BioEnsure as their first product in 2017 and have since developed bacterial inoculants, designed to work in tandem with the fungal endophytes. The team handles all their own manufacturing at their headquarters in Seattle, WA, and uses distributors to get their products into the hands of farmers.

Biological inputs are not a new concept, but they have been a smidge controversial. Independent research often struggles to verify that living organisms listed on product labels are actually present in the bottle on the shelf. Between 2013 and 2015, the Oregon Department of Agriculture Fertilizer Program tested products claiming to contain beneficial living organisms. Only 9 of 51 products claiming to contain living bacteria met their guarantees; Trichoderma was unable to be cultured from any of the 14 products that claimed to contain them. Yet, retailers often sell biologicals at premium prices.

Rodriguez is well aware of the pitfalls of pitching biologicals.

“There are a lot of products on the market that just don’t have anything living in them—I realized we have to control that. We built our own manufacturing system, and we do everything here,” Rodriguez says. “When it goes out the door, we know exactly what’s in it, how much, what’s alive, what the CFUs [colony-forming units] are.”

Now, Adaptive Symbiotic Technologies sells BioEnsure in both liquid and powder formulations. They’ve documented success applying it directly to seeds as a powder, as an in-furrow treatment at planting, and as foliar spray applied to plants, even late in reproductive stages.

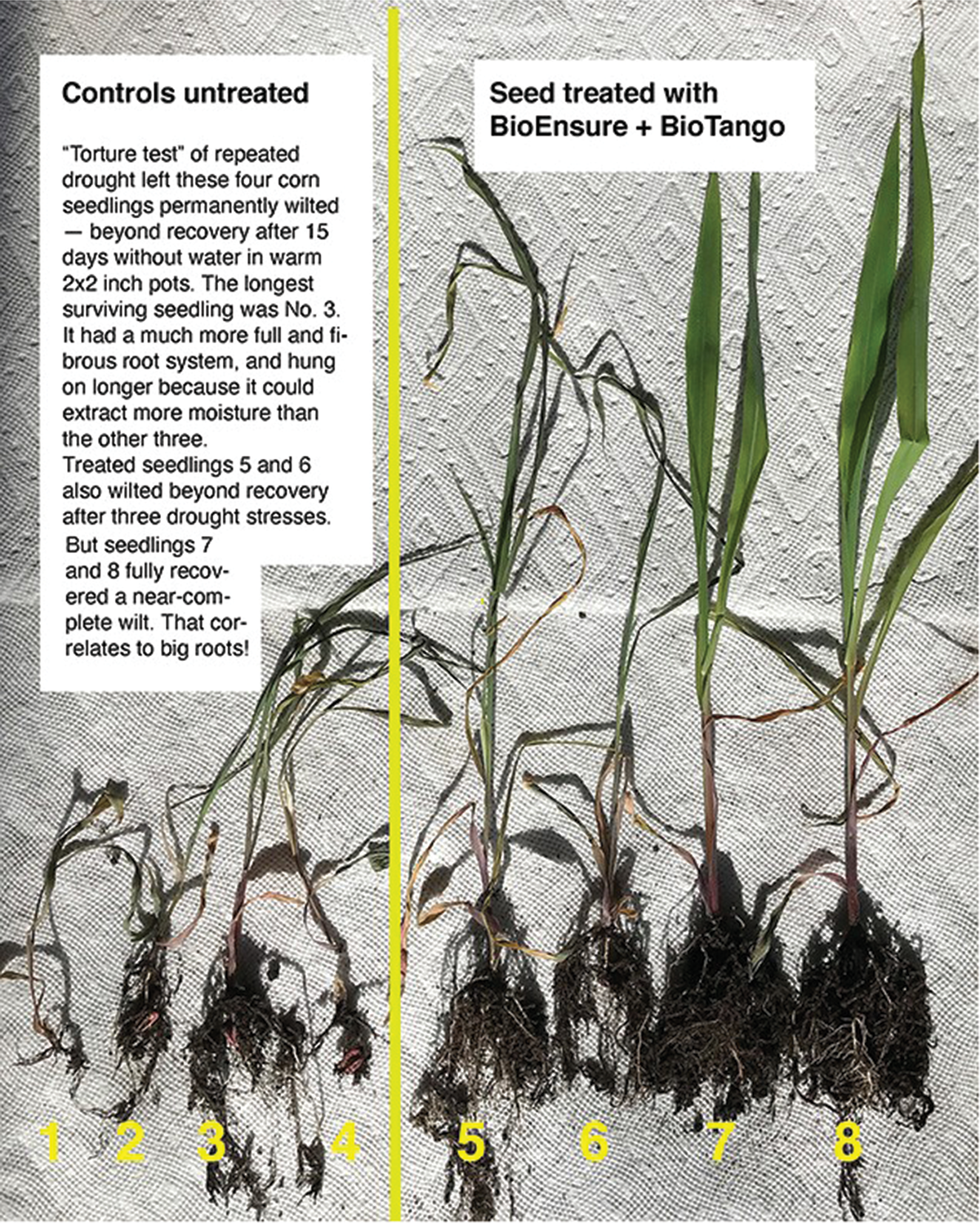

Jerry Carlson, research officer for Renewable Farming, LLC, is among U.S. distributors testing out the product with clients. Independently, Carlson ran some greenhouse trials with inoculated and control corn seedlings at the V2 stage, drying them out to see how they recover. His homegrown data shows foliar spray-treated corn seedlings recovering after two rounds of drought stress while control plants wilt and die. Carlson also has an “innovator” client trying out the product on the field scale.

“My client that’s been at this for two years, he tried it as a planter box treatment and in-furrow,” Carlson says. “His only worry was about getting the treatment on evenly in the planter box—you’re talking one-tenth of a gram…you put this little dab out there. Farmers think more ought to be better, so they heavy it up. But there’s a million organisms per seed! It’s a tough concept to grab onto.”

Carlson points out something that looks shocking after dealing with nutrient quantities in pounds per acre: the teeny tiny application rates. For example, Adaptive Symbiotic Technologies recommends a BioEnsure application rate of 0.5 to 1.0 fl oz per 10 ac, or 0.05 to 0.25 fl oz per 100 lb of seed, depending on the crop. It works with all commonly used fungicides, fertilizers, and equipment and has a shelf life of one year in the bottle or applied to seeds. Rodriguez quotes the cost of applying BioEnsure and its paired bacterial inoculant, BioTango, as somewhere between US$8–21 per acre, depending on application method and crop type.

“Suppose you apply BioEnsure as a foliar spray for about $8 an acre. If you get just two extra bushels of corn, and you don’t charge any cost for spraying because you’re piggy-backing it with a nutrient or herbicide, then you’ve more than paid for it,” Carlson says.

For both large- and small-scale farming operations, a product that can help farmers buffer yields when stresses eat away at crops is a huge development, especially with changing climate already pushing growing regions to their limits. With the dedicated research of scientists like Regina Redman, Rusty Rodriguez, and their teams of researchers and producers testing out products on the ground, we’re closer to incorporating the microbiome as a beneficial in a controlled way.

“We’re at the point where we’re really starting to understand that plant microbiomes drive human health, plant health, global climate health,” Trippe says. “The idea that we can manipulate that to develop products and to feed a growing global population? That’s just incredible.”

And as for that smoking gun?

“We’ve spent a ton of time—an embarrassing amount of time—trying to figure it out,” Rodriguez says. “When you look at the RNA of an inoculated plant next to a control, they’re completely different. These fungi change the gene expression pattern across the entire metabolic spectrum, up and down. We gave up on that smoking gun idea when it was like, which of these thousand genes are we going to look at?”

Rodriguez explains that his best bet is that the fungi suppress the release of reactive oxygen species, which are signaling molecules unleashed as the first step in many pathways related to plant stress. But there’s still plenty of room for research.

Even if we can’t pinpoint why, exactly, the relationships between microbes and plants drive such drastically different results under changing climatic conditions, researchers like Redman and Rodriguez are pushing forward. They’re driving our understanding of the microbial community that grows around and within plants, and in doing so, helping us weather the changing climate and provide food for our growing global population.

Dig Deeper

- You can view Dr. Rusty Rodriguez’s talk at the 2020 Virtual Annual Meeting, titled “Adapting Crops to Abiotic Stress Via Symbiotic Communication with Fungal Endophytes,” here: https://bit.ly/3zo54Ed.

- The full symposium from the meeting, “Hot, Dry, and Salty: Plant–Microbe Interactions that Lead to Enhanced Productivity in Native and Managed Ecosystems,” is available here: https://bit.ly/3iCiMgU.

- The full report on the Securing Water for Food (SWFF) grand challenge can be found here: https://bit.ly/3wAOW0c.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.