Five tips for effective transdisciplinary research

- Vadose Zone Journal recently published a collection of papers in a special section titled, “Transdisciplinary Contributions and Opportunities in Soil Physical Hydrology.”

- Jan Hopmans contributed a review article parsing out the meaning of transdisciplinary research and how soil hydrology’s future relies on both strong collaboration and strong disciplinary work.

- Hopmans offers five tips for effective transdisciplinary research that can help soil hydrologists—and all other scientists—engage with big research questions while maintaining a strong disciplinary foundation.

A recent special section in Vadose Zone Journal titled “Transdisciplinary Contributions and Opportunities in Soil Physical Hydrology” seeks to unite a diverse cross-section of research from soil scientists across the world.

The special section was inspired by a symposium presented at the 2019 Annual Meeting in San Antonio, TX, centered on the research of Jan Hopmans who is a 36-year member and former president of SSSA, former editor of Vadose Zone Journal, and Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Soil Hydrology at the University of California, Davis.

Hopmans published a review on the state of transdisciplinary research in soil hydrology (https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20085). In the review, he offers his views on the future of collaborative research and tips for early career researchers and educators for becoming involved—without losing the heart of soil science as a discipline.

Transdisciplinary Research

“Certainly, in the last few decades, science has changed,” Hopmans says. “It’s becoming much more social in some ways. Scientists are increasingly interested in being involved with societal issues.”

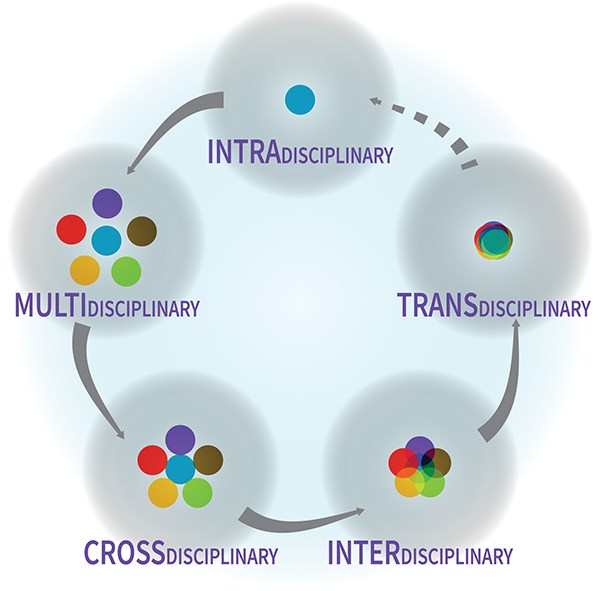

This interest in solving the most pressing issues facing society is something that requires collaboration. Transdisciplinary research is the final step in the collaborative process, moving from work within a discipline—intradisciplinary, basic research—through stages of cooperation with other disciplines. It integrates viewpoints and problem-solving perspectives from multiple disciplines, including nonacademic stakeholders like politicians and community members (see Figure 1).

“By transcending the boundaries of disciplinary perspectives, new intellectual frameworks and disciplines may emerge from interdisciplinary research groupings involving non-academics,” Hopmans writes.

Soil hydrology has a place at the table where these big-picture conversations are happening. It is, after all, a discipline focused on the medium that impacts all facets of life on earth.

“The mechanisms of soils control what we eat, what we drink, what we breath. Soil biology and microbiology are related to human health,” Hopmans says.

Here, Hopmans offers tips for getting involved with big-picture research while still honoring one’s disciplinary roots and all the work to be done in one’s own discipline. To solve the biggest problems facing our planet, we need both basic research and transdisciplinary collaboration that puts foundational research to work in real-world applications.

Five Tips for Effective Transdisciplinary Research

1. Be an Expert in Your Discipline

“Before you start working with other disciplines, you need to be knowledgeable in your field,” Hopmans says. “If you don’t know your own field, you might not be able to offer valuable input—or worse: you might make the wrong case! And that would be a disservice to the team.”

For the eager early career scientist, it’s important to evolve through a natural progression of knowledge. As Hopmans points out, it can be ineffective to make cases for your discipline without a strong foundation in the science. So he advises building a strong research record before diving headfirst into transdisciplinary research.

2. Incorporate Real-World, Multi-disciplinary Problem-Solving in Existing Curricula

Like any other skill, practice makes perfect. Hopmans suggests that educators incorporate discussions of real-world problems within curricula to offer students a chance to hone their transdisciplinary-thinking skills. Plus, collaborative think tanks in low-stakes zones let more senior, skilled researchers help students and early career scientists work through problems without repercussions.

3. Develop Communication Skills

“Being able to translate your research to non-scientists is increasingly important,” Hopmans says. “Whether it’s social media or working with politicians or congressional representatives, they must be able to understand your science at a certain level, so they can make the right decisions.”

“ Transdisciplinary research is about being engaged, as a scientist, with societal issues. It’s really about being able to participate and be of service to society. ”

For students and early career scientists, finding ways to frame your research so that it is accessible for policymakers and the public can make all the difference in creating engagement. But it’s not easy. Even working with scientists from different disciplines can create communication barriers. Early collaborative work centers around finding a common language before tackling big problems.

“You have to have a good understanding of what the issues are from all parties; once you identify the main problem, then you can proceed,” Hopmans says. “But we can work on communication beforehand. How do you listen rather than just talk? How do you participate in larger group discussions? How do you write for the layperson, rather than for other scientists? You can learn all of that, and we can create learning environments that foster it.”

4. Engage in Mentorship

Mentorship can make a huge difference in perspective for researchers on both ends of the career timeline. For early career scientists, mentorship is a rudder that can steer them through the rough waters of involvement in transdisciplinary projects.

Through careful collaboration in stages—perhaps first with neighboring scientific disciplines, then with a broader swath of climate and environment researchers, and finally with non-academic stakeholders and politicians—a researcher will better understand the issues at hand and have collaborative experience to back them.

5. Value Transdisciplinary Work

Finally, Hopmans posits that transdisciplinary research is an area that needs to hold value in evaluations of academic researchers.

“These really big research projects generate papers with 10, 20 authors,” Hopmans says. “You need to be able to demonstrate that you made a contribution, and to get credit for that work—and it can be a lot of work.”

On the Role of Soil Hydrology

“Transdisciplinary research is about being engaged, as a scientist, with societal issues,” Hopmans says. “It’s really about being able to participate and be of service to society.”

Soil scientists are uniquely positioned at the nexus of environmental, atmospheric, and agricultural research. Soil health influences agricultural production, food security, atmospheric and environmental pollution, and water quality. With ties to all these disciplines and areas for improvement, transdisciplinary research—with a strong emphasis on sound disciplinary foundations—is the way forward.

Dig Deeper

Transdisciplinary Soil Hydrology,” at https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20085. This is part of a special section, titled, “Transdisciplinary Contributions and Opportunities in Soil Physical Hydrology,” available at https://bit.ly/3qNGmJg.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.