Stakes high for organic farmers assessing nitrogen mineralization rates

New Research Seeks to Help Predict Speed and Rate at Which Nitrogen Gets Released to Crops

- Organic farming is a $50 billion industry in the U.S., involving more than 5 million certified acres of farmland and more than 14,000 farms.

- Organic farmers can only use organic soil amendments—fertilizers—which aren’t as thoroughly tested as conventional fertilizers and often tend to come from local sources. Thus, figuring out how essential nutrients like nitrogen will be released to their crops can be a challenge.

- Two new studies aim to help farmers predict how fast and how much nitrogen will be released.

Organic farming is a $50 billion industry in the U.S., involving more than 5 million certified acres of farmland and more than 14,000 farms. Organic farmers can only use organic soil amendments— fertilizers—which aren’t as thoroughly tested as conventional fertilizers and often tend to come from local sources. Figuring out how essential nutrients like nitrogen will be released to their crops can be a challenge. Two new studies aim to help farmers predict how fast and how much nitrogen will be released.

Predicting nitrogen mineralization—how quickly and thoroughly organic forms of nitrogen convert to inorganic nitrogen, which is the form plants need—is important for farmers, so they know what type of amendments to apply to their crops and when and how much to apply, says Kate Cassity-Duffey, a soil scientist at the University of Georgia and lead author of a recent study in the Soil Science Society of America Journal (https://doi.org/10.1002/saj2.20037).

But there are huge differences in the net nitrogen mineralization from each type of fertilizer, Cassity-Duffey says. There are also significant differences within a single type of fertilizer—not all feather meals are created equal, for example. Field conditions like temperature and moisture also affect net mineralization. With all this variability, it can be quite challenging for farmers to know how to handle fertilization.

Two Teams, Two Approaches

Two research teams on opposite sides of the U.S. recently took two different approaches to try to add some predictability to the nitrogen mineralization question. Both looked at the rate of nitrogen mineralization in multiple types of organic fertilizers over a growing season.

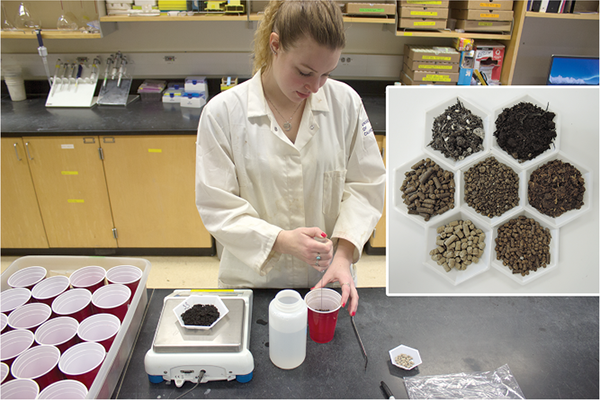

Cassity-Duffey and her colleagues tested the nitrogen mineralization rates of 22 commercial organic fertilizers, 15 poultry litters (manure, spilled food, bedding materials and feathers), and 11 composted materials used in organic farms around Georgia. In California, Patricia Lazicki, a doctoral candidate in soils and biogeochemistry at the University of California–Davis, and her colleagues also tested nitrogen mineralization rates in multiple classes of organic amendments used in California: composted manures, composted yard wastes, commercial pelleted and granular proprietary fertilizer blends, slaughter waste products, and liquid fertilizers like hydrolyzed fish fertilizer. Results were published in the Journal of Environmental Quality (https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20030).

Both teams found a “huge range” in how much nitrogen was mineralized among the amendments they tested, Lazicki says. For example, she says, pelleted guano mineralized 90% of its nitrogen; composted yard waste, on the other hand, ranged from 5% mineralization down to 5% immobilization—a decrease in the plant-available nitrogen.

Cassity-Duffey also found huge variability, from nitrogen immobilization in several of the composts to 93% mineralization in one of the commercial fertilizers. Variability occurred even within a fertilizer type, she says. In poultry litters, for example, between 10 and 55% of nitrogen became usable by the plants.

Predicting Amount of Nitrogen Mineralized

The good news is, though, that both teams found ways to predict how much nitrogen would be mineralized, based on some initial measurable properties in the amendments.

Cassity-Duffey’s team created an equation and an online calculator (http://aesl.ces.uga.edu/calculators/nitrogen/) that could allow anyone with knowledge of the initial total nitrogen of an amendment—something that is not hard or expensive to measure—to determine the net rate and amount of nitrogen mineralized from a product. “It is important to know both the amount of total mineralizable nitrogen and to be able to predict the rate of mineralization to help farmers better understand how the nitrogen is released and to match timing and rates to plant needs,” Cassity-Duffey says.

That information, she says, allows farmers to “make better selections based on how these materials behave.” For example, she says, if farmers are growing broccoli in the winter and the soil is colder (less nitrogen mineralization), they might add blood meal instead of a slower-release fertilizer. If they are growing tomatoes, they could use a different fertilizer that has a longer release or add more during the growing season. If a farmer applied the wrong fertilizer in the hot sun or in a particularly dry period, for example, it might just “sit there” or it might volatize and be lost to the air.

Local soil-testing labs can measure the total nitrogen in an amendment. “Plug that total nitrogen into our equation, and we could give you a pretty good estimate of how much nitrogen could become available” for plants, Cassity-Duffey says. “The idea is that you can measure this one variable and hopefully get a pretty good idea of a much more complex variable—the actual release.” But the calculator even adjusts for field conditions in Georgia, just by entering a zip code and syncing with the state’s weather station data. This information “allows farmers to add additional fertilizers if they see something isn’t right.” Or vice versa, she adds.

Rather than relying on total nitrogen, Lazicki and her colleagues turned to initial carbon-to-nitrogen ratios in the amendments they tested. They found that the amount of plant-available nitrogen correlated well with initial carbon-to-nitrogen ratios over time, allowing them to predict nitrogen mineralization. The patterns suggest that amendments with high initial nitrogen levels (lower ratio) released nitrogen very quickly to plants and then leveled off. Amendments with lower initial nitrogen levels released nitrogen more slowly but kept releasing longer, she says. The yard waste compost they examined, with a high ratio, locked up nitrogen. This result matched what Cassity-Duffey’s team found.

In fact, Lazicki says, “a lot of the findings were really similar” between her study and Cassity-Duffey’s. Feather meal and yard waste composts followed virtually the same curve in both studies, for example, Lazicki says. Having similar findings helps support each other’s results.

Laying the Foundation for Further Work

Both scientists are excited about the potential to help organic farmers, but they also both agree that these studies are laying the foundation for further work.

“I’d like to see even more studies that can confirm these findings in the field,” Lazicki says. It would be interesting to see how plants and their microbial communities change the equation, especially for amendments like composts where it may take a more diverse community to break them down.

Another question, Lazicki says, especially in California where a new law mandates that 75% of organic waste be composted, is if composts could be co-applied with other amendments to both use the glut of new compost materials and to supply the right amount of nitrogen to plants. California law also requires that growers in some regions complete a Nutrient Management Plan for all irrigated acreage to decrease nitrogen leaching into local water sources. Knowing the available nitrogen for a given fertilizer would be helpful, Lazicki says. For example, she says, “100 pounds of nitrogen added as yard waste compost won’t have the same environmental fate as 100 pounds of nitrogen added as urea.”

“We have to be careful of the application of these materials,” Cassity-Duffey says. “Just because they’re organic doesn’t mean they don’t have the potential to provide too much nutrients, which can lead to runoff and other problems.”

In the end, it is all about helping the farmers get tools to make better fertilizer decisions, Cassity-Duffey says. Preliminary research suggests it is possible that many organic farmers are overapplying or underapplying fertilizer, she says. “Right now, when we make fertilizer recommendations, we assume soil doesn’t have any [available] nitrogen,” so fertilizers are applied based on what plants will need, not taking into account what may be present in the soil. “But these rich, organically managed soils do have available nitrogen,” she says, so in the future, scientists would like to be able to determine what’s already in the organic systems. Knowing that would allow farmers to cut back on their applications, which would help both the pocketbook and the environment.

Dig Deeper

Check out the original research discussed in this article: “Nitrogen Mineralization from Organic Materials and Fertilizers: Predicting N Release” from the Soil Science Society of America Journal (https://doi.org/10.1002/saj2.20037) and “Nitrogen Mineralization from Organic Amendments Is Variable but Predictable” from the Journal of Environmental Quality (https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20030).

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.