Oysters clear the waters, but do they muddy the soil?

- Oyster filter feeding expels N- and C-rich biodeposits onto soils beneath aquaculture racks.

- Soils and infauna are capable of processing considerable amounts of oyster-derived N and C inputs.

- Oyster aquaculture did not appear to have many lasting effects to the soil environment, either positive or negative.

If you need to clean up a waterway, plant an oyster farm. Oysters have been shown to improve water quality by removing nitrogen and other nutrients that in excess can cause dead zones and other problems. But even great natural filters like oysters can’t store 100% of what they take in. So, researchers decided to investigate what happens to the seafloor soils beneath oyster farms where copious amounts of poop hit the ground. Their findings, published in the Journal of Environmental Quality (https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2019.03.0099), were surprisingly positive.

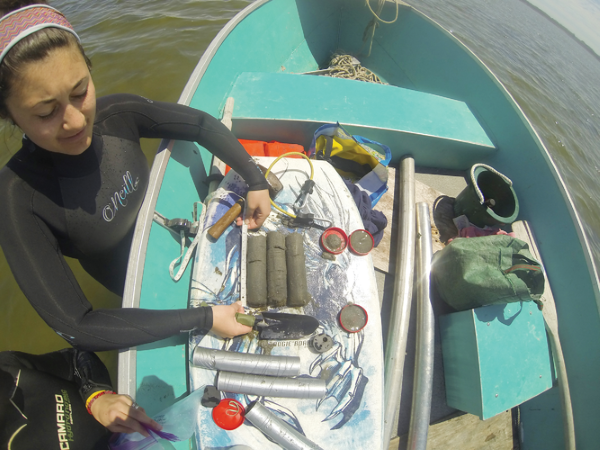

Chelsea Duball, a doctoral student at the University of Wyoming, and colleagues at the University of Rhode Island and the University of Saint Andrews studied eight different sites along coastal lagoons in Rhode Island. The sites ranged in age from zero years of aquaculture use (a control site) to 21 years of aquaculture use.

Aquaculture—farming in the water—has grown significantly in the past decade in the U.S. Aquaculture values are up more than 25%, and oyster production has increased 75% in 10 years; across southern New England, those numbers are even higher. Part of the reason aquaculture has increased is due to oysters’ ability to clean up water. Research has shown, for example, that oyster cultivation in the Potomac River estuary could remove 100% of the nitrogen that is currently entering the river if oyster farms covered just 40% of the riverbed. Removing nitrogen helps with eutrophication, the buildup of nutrients that causes phytoplankton blooms, oxygen depletion, and dead zones.

Generally, oyster farms are made up of thousands of oysters held in mesh bags on top of racks about 8 to 10 cm above the seafloor, though sometimes higher. There, they eat the algae and other nutrients in the water column while the tide washes over them as they grow large enough to be harvested. As they grow, farmers change the mesh bags to grade them out, so the same-sized oysters are all growing together. Oyster racks are usually barely visible if not invisible at the surface.

The lagoons that Duball and her colleagues studied were similar: They have significant nitrogen runoff, they are shallow, and they are all on the same sandy soil type that provides a stable substrate for oyster racks to sit on and oyster farmers to walk on. The size of the oyster farms varied, but the average was about 500 oysters per square meter.

At each study site, Duball and her colleagues collected underwater soil cores up to 20 cm deep below the oyster racks. They measured the physical and chemical properties of the soils—parameters such as nitrogen and carbon content, soil sulfides, and bulk densities—and examined the “benthic infauna,” the insects, microbes, and other animals living in those subaqueous soils.

For the seven preexisting aquaculture sites, the team studied what naturally had been occurring over the years. Because they had such a varied study period—5 to 21 years for the preexisting sites—the team could characterize both shorter- and longer-term effects of aquaculture on the soils.

Few Lasting Effects to Soil Environment

The team expected to see physical, chemical, and biological changes to the soil that increased with time and increased with oyster density, but they didn’t, Duball says.

“We found in that zero- to 21-year gradient, there weren’t many lasting effects to the soil environment, either positive or negative,” she says.

For the control site, where there was no preexisting aquaculture, the team applied concentrated biodeposits—oyster feces—to the soils to simulate what various densities of oysters would deposit over a week. During that short-term impact study, surprisingly, “at all time points (zero to seven days), we found no impacts or even trace of those biodeposits within the soil environment, even at the highest stocking density [2,000 oysters per square meter] loading.” The biodeposits are very fast sinking, she notes. The finding “presumes that [over the short term], something is processing those materials quickly or they’re going elsewhere,” she says. The assumption is that the deposit feeders in the soils must be processing the feces. The team did find higher levels of sulfides at each aquaculture site compared with the control sites and regardless of age, which indicates there could be “some kind of organic enrichment overloading the environment,” she says, but it didn’t seem to affect the deposit feeders even though sulfides can be toxic to some species.

Distinct Disturbances Revealed

Intriguingly, Duball says, the infauna varied from site to site. For example, every site that was older than five years had a higher abundance of deposit-feeding organisms, opportunistic organisms like polychaetes and lower-order worms that “tend to thrive in poor conditions like those of high organic enrichment,” she says. The team also found other polychaetes like Capitella capitata that are indicative of site disturbances, she says. Capitella capitata is one of the first organisms to come back after a disturbance—whether the disturbance was organic enrichment, a hurricane, or a person walking around.

“As we observe these communities and their interactions, we start to [understand] if a site has been disturbed,” Duball says. Measuring ground disturbance itself was outside the scope of this study, especially since these are actively farmed aquaculture sites, she notes, but the types of infauna the team observed certainly reveal distinct disturbances.

Further study should look at where the biodeposits and excess nutrients are going, Duball says: Are they going into the oyster tissues and shells? Or are they going into the deposit feeders’ tissues or floating away? Wherever they go, one thing is clear from these sites: The oyster poop doesn’t seem to be affecting the soils. And it’s good to know that, she says, considering how many places are looking into aquaculture for possible business development and as a water remediation strategy.

Dig Deeper

Interested in this topic? Check out the original article in the Journal of Environmental Quality at https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2019.03.0099. Also, our podcast, Field, Lab, Earth, will be releasing an episode about the impacts of oyster aquaculture on subaqueous soils and infauna on 19 June. Listen for free anytime by scanning the QR code below or by visiting https://apple.co/2SpCoGs on Apple devices or https://bit.ly/2Sqf7nM on Android. Subscribe to never miss an episode. CEUs available.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.