A pith(y) solution to a growing problem

Using Wheat Breeding to Combat Wheat Stem Sawfly Infestation

- Wheat stem sawflies are, historically, one of the major wheat pests in the northern Great Plains of the United States, and the damage they cause is spreading.

- One of the best methods for decreasing the impact of WSS is breeding resistant wheat varieties with management changes and cultivation favoring parasitoid populations as secondary options.

- As a part of the International Year of Plant Health, Crop Science highlighted a paper on testing three alleles for stem solidness as a means of combating WSS infestation.

Farmers are driving their combines and watching wheat stems fall down in front of them. It's going to be harder to pick those up—you know you won’t get it all…you’re wondering, ‘How did this happen?’”

David Weaver, an entomologist at Montana State University, describes the effects of one tiny pest: wheat stem sawfly (WSS). With an affinity for making homes in hollow-stemmed grasses, WSS can wreak havoc on a field of wheat.

To the unfamiliar farmer, the sudden lodging of a wheat crop after a windstorm or combine action can be devastating. A near-harvest field that looks promising one day may be filled with downed stems the next.

“It definitely can evoke an emotional response,” Weaver admits.

In Montana alone, WSS were estimated to cause grain yield losses between $50 and $80 million annually (https://tinyurl.com/yb7oky3u). Sawfly infestation decreases grain protein content and kernel weight while lodging at the end of the season results in a 5 to 15% yield loss (https://bit.ly/2XUTu35).

Though WSS is not a new pest—one specimen was collected in Colorado in 1872—populations are increasing. Traditionally, this sawfly was a real bother for growers in the Northern Great Plains, but fields farther south and east are seeing more and more of the diminutive bugs.

“It's our key pest in Nebraska wheat,” Jeff Bradshaw says. An entomologist and extension specialist at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, Bradshaw has been working on the problem of WSS in the Panhandle since 2010. “We’re on the frontline of its expansion, and it has the advantage on us—it's adapted to the High Plains environment and the cool-season grasses that are abundant out here.”

Wheat stem sawfly presents an interesting problem for growers, breeders, entomologists, and ecologists alike: how do you combat a pest when you are growing an ideal host plant in in its native environment?

From management practices to breeding for resistant wheat lines to changing the local environment where wheat is grown, slowing down the impact of wheat stem sawfly requires cooperation across disciplines related to a key crop on the Great Plains.

Cutting Stems Where They Stand

Sawflies, of the family Cephidae, are found the world over. Like many insects, they have adapted to use a certain kind of plant to complete their life cycle. Without hollow-stemmed grasses, the sawfly larvae would be incapable of finding adequate food or shelter to grow, pupate, and emerge as adults.

One species is found across the U.S. landscape: Cephus cinctus Norton. It's is pretty small. To the untrained eye, some populations look like a wasp—they, too, can have broad yellow stripes, but they lack the distinct, tiny wasp waist. Other populations lack the yellow stripes, but all have distinct identifying features.

“Note the smoky wings, dark head and thorax, and bright yellow legs,” Bradshaw says. “There's nothing else you should find in a wheat field that has those features.”

As part of the family Cephidae, WSS have ovipositors—a tube-like organ at the end of the thorax with projections “like the teeth of a saw.” Rather than using this to inject venom in an unlucky victim, as a wasp does, the female sawfly cannot sting you. Instead, the female sawfly's ovipositor deposits eggs. She “tastes” the stems of grasses, after piercing them with her ovipositor to find a good host, until she deposits either fertilized (female) or unfertilized (male) eggs inside.

Once the eggs are inside the hollow cavity of a grass, they grow into cannibalistic larvae, feeding on the plant parenchyma and each other until only one chubby larva remains.

Meanwhile, the larvae are subtly impacting the growth of the wheat plant: they are quietly noshing on nutrients meant for developing grain, leading to yield loss via decreased grain protein content and kernel weight.

Triggered by changing light cues as the summer season wears on, the larva descends through the stem. Near the base of the stem, the grub-like little larva chomps a notch around the base, girdling it. This notch creates a weak point—with any disturbance, from increased wind to even just gravity, the wheat stem will snap and lodge.

The distinct appearance of a “cut” stem and wheat stubble is a telltale sign of sawfly infestation.

Just below its cutting point, the sawfly creates a plug of saliva and frass, or excrement. The plug serves as a makeshift doorway for the adult sawfly that will emerge in the spring.

With its autumn preparations made, the sawfly larva beds down in the crown of the plant, spinning a cocoon and entering the pupa stage of development. It overwinters here, below the ground, emerging from the stubble in the spring when the weather becomes warm enough. The adult sawflies go on to mate and then females oviposit in more grass stems, completing the sawfly life cycle.

As local populations adapt from using native grass species to wheat as host plants, some modern agronomic practices might be helping them thrive. In areas where no-till, wheat–fallow–wheat rotations predominate, sawfly have both summer hosts and undisturbed wheat stubble for winter residence.

“That's a pretty good sawfly conservation system,” Bradshaw says. “Even if you plant a four-crop rotation, there's a spatial component to this. If you have corn growing in last year's wheat fallow, you’d have sawfly emerging from the stubble and cruising underneath the corn canopy and finding wheat.”

Combatting Infestation

A 2020 USDA report on wheat stem sawfly impacts in the western Great Plains posits that “current management practices for the wheat stem sawfly, resistant wheat cultivars and various cultural practices, have not been effective in minimizing losses” (https://bit.ly/3588Kve).

However, leading experts in the field point to three critical junctures in the sawfly life cycle as vulnerable points for attacking this insidious pest: at the larval stage, the pupal stage, and oviposition.

One means of attacking sawfly larvae is using its parasitoid: the Bracon cephi or B. lissogaster wasps. These wasps lay eggs on the newly stung, paralyzed body of the WSS larva present in the wheat stem, using oviposition just like a sawfly.

“The parasitoid latches onto the larva and feeds on its juices,” Bradshaw says. “It forms a pupa higher up in the wheat stem, then reaches maturity and exits the wheat, often before harvest.”

In that case, a researcher splitting a wheat stem at the end of the season might find a dead sawfly and the remnants of the pupal stage of the parasitoid wasp larvae. This indicates that the parasitoid effectively eliminated the sawfly and moved on to another grass to complete a second generation.

“When the parasitoids are effective, they are really effective,” Bradshaw says. “In fields with high parasitoid populations, WSS numbers are highly reduced the following season.”

Bradshaw and his team are studying the relationship of parasitoid pupa to sawfly larvae and are working to understand how the parasitoid overwinters. Frequently, the team has found intermediate wheatgrass near Nebraska wheat fields hosting the second generation of parasitoids over the winter. They have also noted a relationship between the presence of hollow-stemmed grasses in ditches, where water conservation is higher, and the presence of higher parasitoid numbers.

“It could be something as simple as changing county mowing schedules to conserve these ditch grasses, creating homes for parasitoid populations,” Bradshaw says.

Anything the team can do to support parasitoid populations could help the parasite keep sawfly numbers in check.

Likewise, Weaver and his colleagues at Montana State University are exploring how crops that provide nectar might support parasitic wasps along with pollinators.

“We’re looking into how we can support these parasitoid populations by supplying supplemental nutrients,” Weaver says. “It's really early in the process, and we can’t just say something is going to be really easy, like: ‘These parasitic wasps access nectar from peas.’ We already know that isn’t the case. But there's something in crop rotations that's giving them access to nutrients.”

Providing the parasitoids with supplemental nutrients might help them survive longer after emerging. When parasitoids are not successful, it could be because they emerged earlier than sawfly adults and missed their window to parasitize the larvae.

Increasing the length of time a parasitoid can survive before ovipositing in stems with sawfly larvae could increase their effectiveness.

A second means of control is preventing the pupae from emerging from wheat stubble as adult sawflies. Bradshaw, in his work as an extension specialist, describes acting at this stage as a “rescue” treatment for severely affected fields.

“It's not particularly popular, but tilling does prevent sawfly emergence,” Bradshaw says. “Even a mild amount of spring tillage of wheat stubble, even as part of the planting process, overturns the stubble and prevents sawflies from emerging.”

Finally, one of the most effective means of decreasing sawfly spread is using resistant varieties of wheat. Conferring phenotypes of solid stem in wheat prevents the sawfly from either ovipositing in the first place, or if a female does deposit eggs, the larvae are incapable of surviving in a solid pith.

“Sawfly are a nightmare to control, using the number one tool a farmer would think of, which is just going out and spraying. It's not possible,” Weaver says. “That pushes the importance of host plant resistance forward a lot.”

Breeding for Resistance

To examine the effects of stem solidness on both resistance to WSS infestation and agronomic traits, researchers at Montana State University bred and tested three novel alleles derived from three separate wheat varieties. Results were published in Crop Science (https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2019.01.0009). This article is part of a group of articles being highlighted in a special virtual issue of the journal this year to celebrate the International Year of Plant Health (see sidebar).

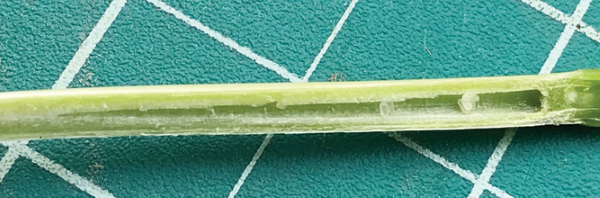

Though not 100% effective, breeding wheat that has a solid stem—a “pith,” or spongy tissue in the center of a wheat stalk”—is one of the best tactics for decreasing WSS impact on a wheat crop. Most modern, adapted wheat cultivars have hollow stems.

“If you have a plant that has to produce more pith, it's using less energy for grain production,” Bradshaw says. “Usually solid-stem varieties have lower yield.”

Jason Cook, Assistant Research Professor and Wheat Trait Integration Breeder and Geneticist at Montana State University, was part of the team examining three different alleles for stem solidness. Cook bred the relevant alleles into adapted wheat lines, creating the genetic material necessary for the team to test their resistance in a sawfly-infested field.

Cook's contribution as an experienced wheat breeder was his use of a distinct genetic marker to ensure that the desired alleles were properly integrated into the adapted wheat line. That is, his team tracked the progress of the new allele from one generation into the next not just through its phenotypic expression, but also with a marker that acted like a bookmark, sticking out of the genetic code.

This allows the team to more effectively and easily select progeny that has the desired allele as they integrate the new allele into an existing line. Cook also “backcrossed” the wheat, inbreeding it until the genes stabilized and all the progeny had the same phenotypic expression.

The three alleles the team tested were for three different manifested stem types: hollow, solid, and a type that begins solid and becomes hollow over time.

The novel allele in which stem solidness is present early in development but disappears later on could be a useful tool for geneticists and breeders in the fight against wheat stem sawfly.

However, the most interesting part of the story is how the team thought to use a stem allele that, by conventional measures, would not look like a great candidate for sawfly resistance.

Traditionally, stem solidness is evaluated at the end of the season. Wheat varieties that have a solid stem when cut through around harvest time are often considered the most resistant to pests. But something happening earlier on in the season was conferring resistance to a variety that looked hollow at the end of the season but was not infested with sawfly larvae.

Weaver's team, in working with an older commercial variety of wheat called “Conan” (yes, after the Barbarian), noticed something strange about its development.

“In the Conan-derived variety, as the stems started to ripen, there was some unusual morphology,” Weaver recalls. “They were partially hollow—they just didn’t look like a regular solid stem. When we looked at it at the beginning of the season, we would see this incredibly firm pith with, oftentimes, some dead eggs or small larvae that have died trying to get going in a solid pith.”

As many farmers worry that solid-stem varieties will not achieve the same agronomic performance, the existence of the novel, transitory solidness allele serves as a wonderful new addition to the geneticist's toolkit for WSS resistance.

“It could be that the plant produces a pith early on in development, but then resorbs that pith later on in the season as it develops the grain,” Bradshaw says. This phenotype could allay the fears of farmers who want to balance yields with resistance.

“It didn’t look like there was any yield penalty in the Conan variety,” Cook says. “For spring wheat, the Conan allele provided better sawfly resistance compared with the other lines, and it can be hard finding novel sources of resistance.”

A Story of Cross-Disciplinary Cooperation

With traditional measures of sawfly resistance, researchers typically take one key data point: stem solidness at the end of the growing season.

Weaver points out that it was through the cooperation of entomologists and wheat breeders that the novel allele was discovered. Because the Conan-derived allele would test poorly if one only looked at its stem-solidness at the end of the season, the observations of Weaver, his graduate students, and staff members indicated there was something more going on. They brought it to the breeder's attention.

“Our success here is due to the willingness of those working with the germplasm to interact with us, the entomologists,” Weaver says. “It's a case of transdisciplinary work fitting together very nicely. I really need the breeders as much as they need me.”

Moving forward, finding ways to farm that encourage positive relationships between a field and the surrounding environment is key. Planting crops that support pollinators and parasitic wasps, using resistant varieties that thwart evolutionary life cycle adaptations rather than by just killing off pests with insecticide, and acting as stewards of the land: these are all ideas put forward by the three experts interviewed for this article.

“If you really wanted to get rid of sawfly, you’d just stop growing wheat,” Bradshaw says. “But wheat is really a key component of the agroecosystem in the plains, and we’re not going to do that.”

In a world where wheat keeps growing, the work of entomologists in conjunction with breeders creates a broader perspective on how to combat a pest that is native to the landscape.

“The more you delve into a major problem that's hard to solve, the more you need multi-faceted, interdisciplinary cooperation,” Weaver says. “You can’t just use one or two avenues to get to a solution: you’ve got to be broader.”

This emphasis on broad, forward-thinking cooperation fits wonderfully with the aims of the International Year of Plant Health. Not only does the research on sawfly resistance demonstrate innovation in breeding, but it highlights the complex relationships between domesticated and native species, between growers and researchers, and between human beings and the land we steward.

Celebrating the International Year of Plant Health

The United Nations General Assembly declared 2020 the International Year of Plant Health (IYPH). The goal of IYPH is to raise “global awareness on how protecting plant health can help end hunger, reduce poverty, protect the environment, and boost economic development.” You can read more about IYPH here: www.fao.org/plant-health-2020/about/en/.

To increase awareness of research protecting plant health, Crop Science collated a virtual issue featuring relevant, outstanding papers. The paper referenced in this article, “Comparison of Three Alleles at a Major Solid Stem QTL for Wheat Stem Sawfly Resistance and Agronomic Performance in Hexaploid Wheat,” was part of this virtual issue. You can read more papers from the collection here: https://bit.ly/2Ydpyzn.

Crop Science is calling for more papers advancing plant health to be published in a special issue later this year or early 2021. Find out more about submitting your relevant manuscript here: https://bit.ly/36aQf9N. The submission deadline is 31 Aug. 2020.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.