Tracking volatile organic compounds in desert soil

- The Amargosa Desert Research Site in Nevada serves as the home base for long-term studies on water, gas, and contaminant movement through unsaturated desert soil.

- A recent Vadose Zone Journal study highlights 17 years’ worth of research on the presence and distribution of volatile organic compounds in the 100-m-thick vadose zone.

- The study is the first to demonstrate that the deep, arid unsaturated zone can be a major reservoir for biogenic volatile organic compounds.

Mountains line the horizon, as surreal as matte paintings on the set of a Western film. Scrubby creosote and burrobush dot the dry ground. A compound stands sentry within the confines of a chain-link fence. Cradled by the Funeral Mountains to the west and Bare Mountain to the east, the Amargosa Desert Research Site (ADRS) was established in 1976 as a part of the U.S. Geological Survey Low-Level Radioactive Waste Program.

And why, you ask, was it plonked in the middle of the desert?

The site was chosen for its proximity to a commercially operated low-level radioactive waste facility. From 1962 to 1992, the commercial facility was used as a repository for low-level radioactive waste, volatile organic compounds, acids, bases, and other hazardous chemicals.

Arid sites are often preferred for waste disposal. With less water, the logic goes, the less contamination will occur since very little water is present to carry the waste away.

Early studies at the ADRS focused on hydrology—the way water moves through the 100-m-thick unsaturated zone at the site. But in 1995, researchers at the site unexpectedly discovered contaminants deep in the vadose zone.

“It really is a kind of domino effect,” says ASA and SSSA member Brian Andraski, long-time site coordinator and research team co-leader of the ADRS. “We started off looking at liquid water, then documented the importance of water vapor. Then came the question of gas transport; then we discovered the long-distance movement of contaminants through the soil. One discovery leads to new research, which leads to more discovery.”

Seventeen years’ worth of research at the site culminated in a recent Vadose Zone Journal article discussing one kind of contamination: volatile organic compounds, or VOCs (https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2019.05.0047). The bulk of this work was completed after 1997 when the site became a part of the Toxic Substances Hydrology Program, which provided core funding to support ADRS research.

In the study, the VOCs present at the site were mapped. The team took samples both near the surface and throughout the depth of the 100-m-thick unsaturated zone to better understand how contaminants in their gaseous phase move through the soil.

Volatile Organic Compounds

Volatile organic compounds are a diverse group that are united by a common characteristic: low boiling points. At typical environmental temperatures, VOCs are found in their gaseous phase. There are two broad types of VOCs. The first are produced by living organisms called biogenic VOCs (bVOCs). The second are produced anthropogenically through the actions of human beings. In some cases, certain VOCs are produced both through human processes and by other organisms.

For plants and other organisms, bVOCs play an important role in signaling. For example, flowers produce bVOCs to attract pollinators. Large amounts of bVOCs are found in the environment. They contribute to overall air quality and help regulate the climate through formation of fine particles that moderate earth’s radiation budget—that is, the balance in the “budget” of radiation that comes in through earth’s atmosphere (sunlight and UV-A and UV-B rays, to name a few) and the radiant energy that escapes (https://go.nasa.gov/2zU0L9l).

Anthropogenic VOCs include some environmental contaminants with which you may already be familiar. For instance, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were once a component of aerosol sprays that contribute to the depletion of the ozone layer—they have since been phased out of use (https://bit.ly/2yiXNeo). Compounds such as tetrachloroethene (PCE) and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) also contribute to ozone layer depletion. Ozone layer depletion has a nuanced impact on the global climate, changing the way that our atmosphere circulates (https://go.nasa.gov/3dREgRc).

Though atmospheric VOCs are monitored as a component of air quality, their presence in the soil is not well understood. At the ADRS, researchers used long-standing infrastructure installed at the site to map VOC concentrations found at multiple depths throughout the unsaturated zone. The team also analyzed VOC fingerprints: spatial patterns that provide clues to the origin and identity of anthropogenic VOCs versus bVOCs.

Mapping VOCs

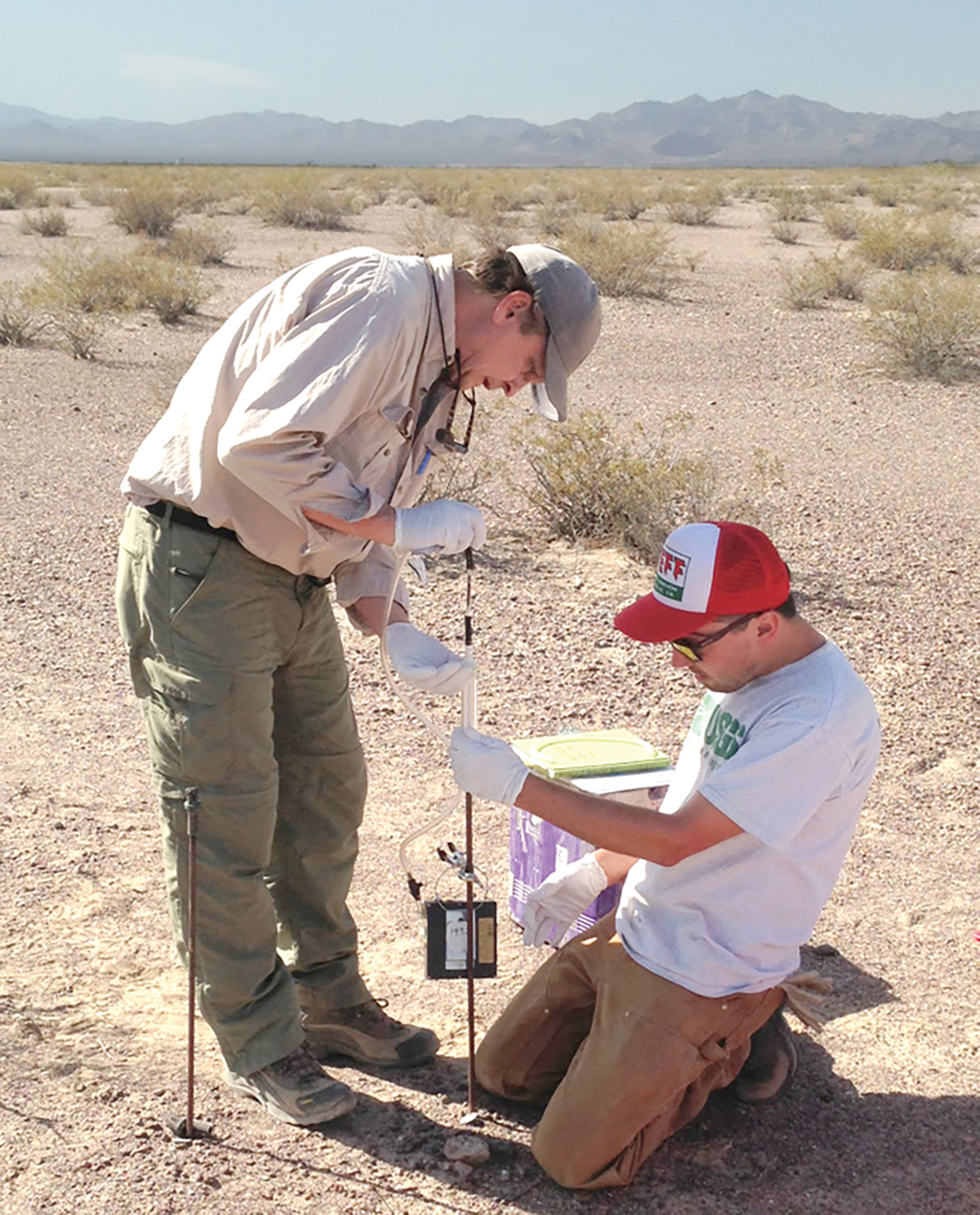

If you were to go for a stroll around the ADRS grounds, you would see small clumps of 10 or 12 plastic tubes sticking up out of the ground like bouquets of flowerless stems. These plastic tubes mark locations for deep sampling. Using a drilling rig, the team drilled through the unsaturated zone, all the way to the water table. Then, at regular intervals, the team added small sampling “pockets.”

Each pocket was created the same way. First, the hole was backfilled to the desired depth. Then a stainless-steel screen was added, then a tube reaching all the way to the soil surface, and then aquarium gravel. The large pores created by the aquarium gravel ensure that air will flow from the soil into the tube at each depth.

This process was repeated at 10-m intervals throughout the soil; these “bouquets” of pipes at the soil surface represent discrete sampling depths.

To obtain an air sample from a certain soil depth, the tubes are purged to collect 1 L of air, pulled through a specially designed resin cartridge that captures VOCs. The samples are put on ice and sent to the lab at Portland State University for analysis.

Sampling at shallow sites follows much the same procedure but with metal tubes driven to depths of 0.5 to 1.5 m. These sites were recently installed on top of low-level radioactive waste disposal trenches.

Answering questions about air flow and contaminant plumes deep in the soil requires this kind of infrastructure. Without the dedicated, well-maintained site, this kind of research would not be possible.

VOC Movement through Unsaturated Soil

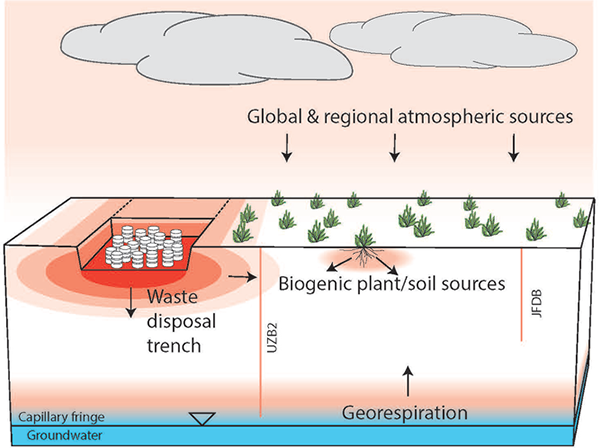

In the arid Amargosa Desert, soil pores are not filled with water. The sheer depth of the unsaturated zone creates a massive air storage space.

In a phenomenon known as barometric pumping, the air moves into and out of soil pores in response to atmospheric pressure. If atmospheric pressure increases, whether from a storm system or just in a daily pressure fluctuation, air is driven into the soil. If atmospheric pressure decreases, air moves out of the soil. The longer the column of air is contained within the soil, the greater the effect a pressure change has.

The same holds true if a surface prevents air flow—barometric pumping can occur horizontally if an air column forms underneath a hard surface like pavement.

In both cases, the complex movements of VOCs through the soil show that contaminants like PCE, CCl4, and CFCs may be traveling farther and deeper than researchers anticipated—never mind the fact that they may be transferred from the soil into the atmosphere.

An Unexpected VOC

As the team mapped concentrations of VOCs collected at different soil depths across the ADRS compound, they neatly traced the movement of plumes through the soil near the waste site.

PCE and CFC-12 were found in elevated concentrations emanating from the mixed-waste trenches. CFC-12 peaked at a depth of 20 to 50 m below the trenches, which range from only 2 to 15 m deep. The plumes are not moving as though carried by water—they are distinctly related to gas transfer in the soil.

Likewise, CCl4 was found in a distinct plume on the southeastern corner of the sampling sites, indicating another source of contamination, likely from another waste disposal site near the ADRS.

This study is the first to show how dense VOCs, like CFC-12, move downward through hundreds of meters of soil profile over decades.

There was one VOC, however, that just was not fitting into the picture the team had created.

“M,p-xylene was the alarm bell that set us off,” Christopher Green says. “It was there, across the site, at levels we weren’t expecting. It really got us thinking that something else was going on here.”

Green, a research hydrologist with the USGS and an SSSA member, mentioned that the bVOCs “flew under the radar” as the team examined the massive concentrations of anthropogenic VOCs from the waste site. Biogenic VOCs were found at elevated levels in the background sampling sites. By taking measurements farther away from known waste repositories, the team gathers points of comparison to understand the elevated levels of contaminants from toxic waste.

The background samples act like the powder used in dusting for fingerprints—they throw the elevated VOC levels from waste sites into relief. However, the elevated m,p-xylene level across sampling sites looked like more than just dust: taken together, it was creating its own fingerprint.

In a lucky turn of events, a paper published by Jardine et al (2010) helped the team answer the question: m,p-xylene is emitted by the creosotebush.

Nicknamed the “little stinker,” the creosotebush is native to the Southwest United States and Mexico. The roots of this bush interact allelopathically with the roots of other plant species. Allelopathy refers to a relationship in which a chemical secreted by one plant inhibits the growth of another.

Prior research indicates creosotebush roots are allelopathic toward both its own seedlings, encouraging a more spread-out population structure, and toward burrobush—another shrubby plant commonly found in the deserts of the Southwestern United States (https://bit.ly/2WwxCtN).

“We were really trying to get at the prevalence, distribution, and recalcitrance of these bVOCs while also trying to understand the extent and evolution of the spread of anthropogenic VOCs at the site,” Green says. “It’s a really interesting mix.”

In both cases, mapping VOCs at the site serves as foundational research for the prevalence and distribution of biogenic compounds in the soil. This study shows, for the first time, that the deep arid unsaturated zone can be a substantial reservoir of diverse species of bVOCs.

On Long-Term Research

Remember that “domino effect” that Andraski mentioned? Both Green and Andraski had nothing but positive things to say about the evolving surprises that come from working on a long-term site like the ADRS.

“If I were at the ADRS for just two years, I might go out and finish a study, and think, ‘Oh, I know exactly what’s happening here,’” Green says. “But when you come back the next year, everything might change. That just kept happening over the course of 17 years at this site.”

The unique combination of intense infrastructure, long-term research, and distinctive methodologies makes this study from Vadose Zone Journal a perfect example of how prioritizing a site for in-depth study can lead to unexpected findings.

“We’ve got decades of data here,” Andraski says. “That’s not typical. Whether its water movement or long-term gas transport, the research we do here is important to understanding fundamental processes in the vadose zone.”

If you consider that the waste disposed of in the soil near the ADRS is in its final resting place, there is no way but long-term research to understand how the complex and potentially harmful components therein will move throughout our landscape. It is work like that done by the ADRS team that helps us see just how what we leave behind moves on.

Dig deeper

Check out the original Vadose Zone Journal article, “Spatial Fingerprinting of Biogenic and Anthropogenic Volatile Organic Compounds in an Arid Unsaturated Zone,” at https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2019.05.0047.

Jardine, K., Abrell, L., Kurc, S. A., Huxman, T., Ortega, J., & Guenther, A. (2010). Volatile organic compound emissions from Larrea tridentata (creosotebush). Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 10(24), 12191–12206. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-12191-2010

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.