The uniformity of nonuniform flow

Understanding Intrinsic Complexity of Water Movement through Soils

- Uniform flow of water through soil is the exception, not the norm.

- A special section in Vadose Zone Journal focuses on nonuniform flow through soils, from experimental tests to refined mathematical models to a historical perspective on the research to date.

- The future of nonuniform flow research will likely involve machine learning/artificial intelligence to better analyze flow on large scales.

Getting water from one point to another with maximum efficiency is no easy task—it's one that has challenged engineers for centuries. The Romans constructed aqueducts, spanning leagues in clever lines across the landscape. Water towers grace skylines within city limits, irrigation ditches lounge next to fields, and sprinkler systems polka-dot residential lawns. It's no surprise that water flowing through the soil itself might be difficult to quantify. After, all, it's finding the path of least resistance, flowing through pores between soil particles and pipes created by worms, insects, and tree roots.

This tendency—for water to move through soils preferentially via macropores and soil pipes—is called nonuniform flow. Nonuniform flow results in water saturating some areas of soil more than others, even under the same rainfall or watering conditions.

It also has undesirable effects on soil conservation and pollution as nutrient rich topsoil is washed away and applied nutrients and pesticides pass through to water reserves without being filtered by the bulk of the soil. Soil pipes can also erode and collapse, forming gullies in farmland or causing infrastructure failure of roads and dams as the soil beneath gives way.

Though scientists have known about nonuniform flow for more than 100 years, the phenomenon is not well understood or quantified. Mathematical models often fail to accurately predict preferential water flow, particularly at larger scales like whole watersheds. Plus, scientists have come to realize that nonuniformity is, in fact, uniform in its prevalence in soil water flow.

“Historically, the classic theory has always revolved around a continuum-equilibrium concept,” says Majdi Abou Najm, the lead guest editor of a special section on nonuniform flow published in Vadose Zone Journal (VZJ). “We assume that capillary action and gravitation are the dominant forces, and the classic theory would try to average them over a domain. But our previous assumption that the classic theory should be able to predict and estimate the bulk of the flow is no longer a valid assumption,” Abou Najm says.

Abou Najm, an assistant professor of soil biophysics at the University of California–Davis, has spent his academic career investigating preferential flow, from his Ph.D. work on soil cracking through to his recent work modeling soil pore structures. Finding more accurate ways to model and calculate the movement of water through soil drove Abou Najm to pitch the idea for the special to VZJ editors.

Abou Najm worked closely with Laurent Lassabatere of the Université de Lyon and Ryan D. Stewart of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, who also served as co-editors. Together, these three guest editors gathered 17 articles for the special section and co-authored the section's introduction.

“We covered a wide range of methodologies, including theoretical and experimental discoveries,” Abou Najm says. “We also covered a wide range of scales, from researchers studying what happens at the level of a single soil fracture up to researchers studying how nonuniform flow behaves and is observed at the level of fields and watersheds.”

The special section presents a unique fusion of experimental and theoretical methods and highlights the importance of technology in advancing soil hydrology research. It also represents the interface between experimentalists and theorists, opening a dialogue between laboratory-based models and practical applications in the field.

The Historical Perspective

Historically, preferential flow was thought to be the exception to the rule with uniform flow marking the majority of water movement. Soil physicists and hydrologists relied primarily on Darcy's Law (Darcy, 1856) to calculate flow.

Developed by Henry Darcy in 1856, Darcian flow has a linear flux rate that is directly related to the applied pressure gradient in the soil. That is, water shows laminar flow through the soil from areas of high pressure to low pressure, and the rate of flow depends both on the material and on the viscosity of the fluid moving through the medium.

Laminar flow calculations rely on the assumption that particles within the fluid do not interact but travel in smooth, straight paths. However, much of flow is turbulent with particles interacting and moving irregularly. This can increase shear stress on macropores, enlarging them into soil pipes as soil particles on the walls are eroded and washed away.

In short, Darcy's Law does a passable job explaining flux rates through a homogenous medium like sand, but it does not adequately describe flow through soil mediums that change across a landscape, nor does it account for turbulent flow. Even similar, modified equations like the physicist Buckingham's equation (1907), predicated on capillary action, do not fully account for the parameters in the soil that affect flow.

One paper in the special section, authored by distinguished Emeritus Professor in Hydrology at Lancaster University, Keith Beven, examines the history of research on nonuniform flow in soil (https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2018.08.0153). Provocatively titled, “A Century of Denial: Preferential and Nonequilibrium Water Flow in Soils, 1864-1984,” Beven's paper highlights the instances of knowledge of preferential flow and how researchers often disregarded this knowledge in their calculations and experimentation.

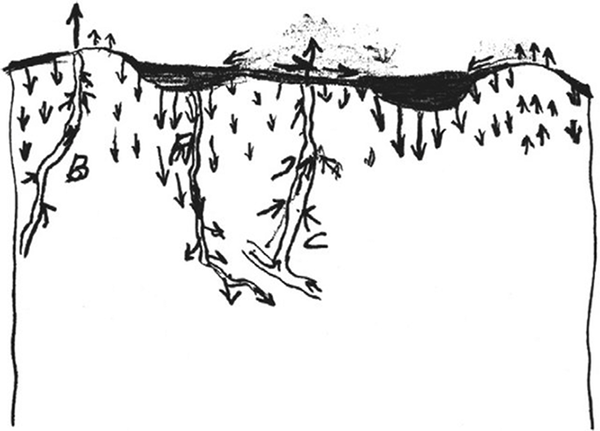

One early example of such knowledge appears in an unpublished monograph, Infiltration of Rainfall, hand-sketched by Robert Horton in 1933 (see Figure 1). The sketch demonstrates Horton's knowledge that water accumulates in basins and depressions and flows deeper into the soil in areas where perforations, insect or worm tunnels, or tree roots provide large pores for water flow.

Beven's paper also discusses early work on soil pipes, macropore flow models, nonequilibrium fingering, and flood runoff. The paper ends its probing at the cutoff year of 1984. Current research relies more heavily on mathematical modeling and imaging techniques that were not prevalent at the time. As technology develops, hydrologists and soil physicists are taking novel approaches to quantify and model a difficult problem.

New Techniques in Modeling

For soil hydrologists, effective modeling has been limited by scale.

At small scales, like in a single laboratory experiment on soil flow conducted on a sample of unsaturated sand, Darcy's Law appears to be linear. Pressure and flux appear to be positively correlated. When scaled up to the level of a single field—or even farther to an entire watershed, with slopes, macropores, and different soil types—the linear relationship does not hold.

“We need to respect intrinsic complexity as a fundamental property of natural geosystems,” Abou Najm says. Current research methods do not take into account all of the variables present in the soil, leading to models that do not match up with experimental data.

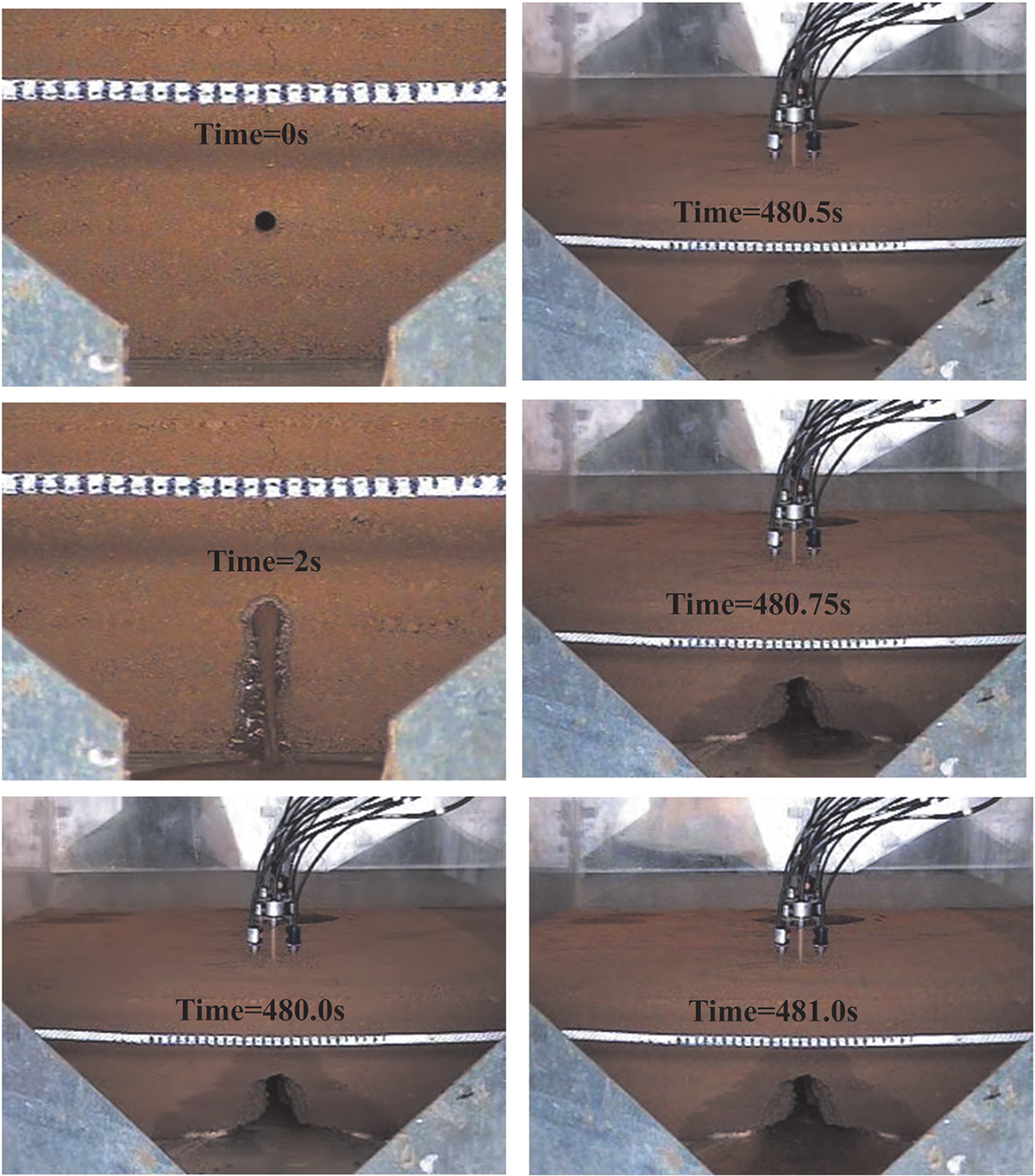

Soil pores were the subject of one standout paper in the special section. A team of researchers, including John Nieber of the University of Minnesota–St. Paul, Glenn Wilson of the USDA-ARS National Sedimentation Lab, and Garey Fox of North Carolina State University, collaborated to model internal erosion in soil pipes (https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2018.09.0175).

“The methodology we use is a bit different than what most soil scientists use,” Nieber says. “Preferential flow, which soil scientists have dealt with for a hundred years but have only been trying to quantify and model in the last…40 years or so, violates the assumptions of Darcian flow. It's more turbulent. Darcy's Law ignores the effects of inertia, which is very important in turbulent flow. Those facts are accounted for in the analysis we did.”

Using experimental data on sediment transport in soil pipes collected in controlled laboratory conditions by Wilson (2009, 2011), the team applied turbulent flow modeling equations to test model predictions against experimental data.

The team used turbulent flow modeling developed in aerodynamics research and pipeline hydraulics. Using the Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes equation and incorporating shear stress and the effects of sediment on turbulent flow, Nieber and his team tested a mathematical model against experimental data for erosion within a soil pipe.

The pipe, originally 6 mm in diameter for its entire length, showed the highest shear stress at the water entrance. This was in contrast to the hypothesis that shear stress would be uniform along the length of the pipe. The non-uniformity of shear stress means that the pipe diameter became larger in some places more quickly than others. This finding requires further research to understand. However, the model they developed agrees with the experimental results, providing an important foundation for further research on turbulent flow and erosion in soil pipes.

The researchers also relied on several key assumptions to model erosion in the laboratory soil pipe. They assumed that sediment particle-particle interactions and fluid-particle interactions were negligible; they also assumed that the sediment concentration within the fluid did not affect fluid properties. They hope to incorporate parameters accounting for these interactions in further research.

In short, the team's findings provide a solid baseline for additional research, hopefully helping hydrologists and soil scientists create models that can predict the rates of erosion in soil pipes. Better models at small scales can then be applied as part of larger-scale predictions of water behavior over greater land masses.

The Future of Nonuniform Flow Research

The development of stronger imaging technology and more powerful computational methods will critically help hydrologists. To understand the complex nature of flow on larger scales, researchers need to be able to both visualize soil and geosystem properties and work with data analysis methods capable of handling large amounts of inputs at multiple parameters.

Both Nieber and Abou Najm highlighted artificial intelligence and machine learning as up-and-coming means of analyzing nonuniform flow.

“If you went back five years, no one was really talking about using something like [artificial intelligence] in hydrology,” Nieber says. “But if you go to the American Geophysical Union meetings now, I'd say 10 to 20% of the presentations in hydrology involve machine-learning applications.”

Machine learning, critically, can help scientists analyze data in layers. Scientists input accurate parameters for each small scale within a larger geosystem, and machine learning can take the data and integrate it.

“What we currently do, which is similar, but in a very, very primitive way, is something called data-transfer functions,” Abou Najm says. “It's basically a statistical relationship where some of the basic parameters like bulk density and percentage of sand, silt, and clay are used to predict other parameters like wetness or hydraulic conductivity. Artificial intelligence would help us take those to a whole new level and enable us to predict at higher scales in space and time.”

Other methods like micro-CT (micro-computed tomography) scanning and remote sensing will add additional resources for scientists to understand flow, both uniform and nonuniform, on larger scales.

As Abou Najm phrases it, “My hope is that research will continue to be strategic and address questions we can generalize, not only investing funding to solve one local problem. It's very important that we discover more about processes that are not just scale dependent: we need to respect intrinsic complexity as a fundamental property of natural geosystems.”

DIG DEEPER

Check out the special section, “Nonuniform Flow across Vadose Zone Scales II” in Volume 18 of Vadose Zone Journal at https://dl.sciencesocieties.org/publications/vzj/tocs/18/1.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.