Mentor or mentee? An early career perspective

An “early career member” is anyone who recently graduated from college and is generally within the first decade of their career. This is a time of major change when most will suddenly find themselves in the dual role of being a mentor, while yet being a mentee, in the early stages of their careers. The partitioning of being mentor vs. mentee tends to split more equally during this period of life. Your scale of contributions to these roles may also peak during this time. Below, I briefly note some types, structures, benefits, and pitfalls of mentor–mentee relations. Moreover, I provide some viewpoints I have gained in the seven years since my last degree. I hope this article will provide encouragement and vigilance as you experience this dual mentor–mentee role, regardless of where you are at in your career.

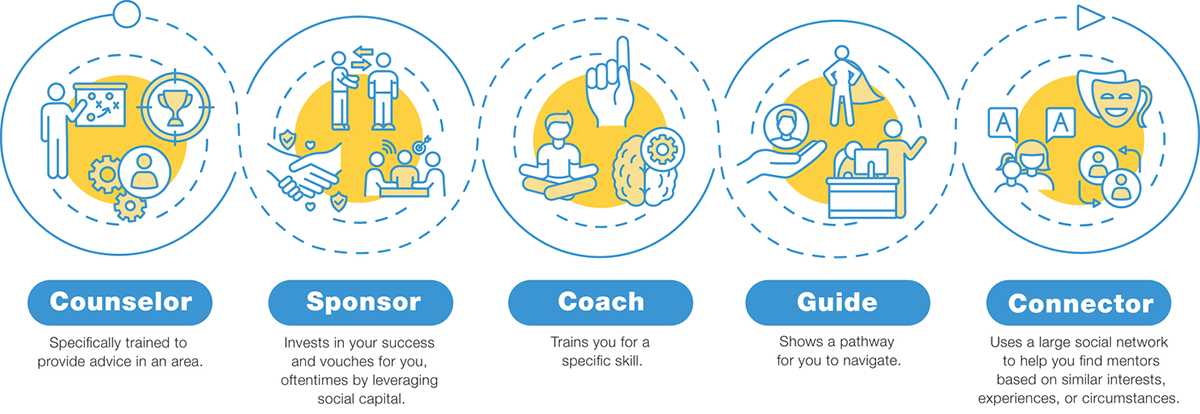

Mentor, Counselor, Sponsor, Coach, and Guide—Is There a Difference?

The dictionary defines mentor as “a trusted counselor or guide.” The term actually comes from the character “Mentor” in the ancient Greek literature The Odyssey, by Homer. In this sequel to the Iliad, Odysseus is lost at sea after a brutal war. During his absence, a trusted friend, Mentor, helps to guide Odysseus’s son from birth to adulthood.

In general, mentor is a broad category containing many types of relationships. Counselor, sponsor, coach, guide, connector, etc. are examples of mentors. Each has specific perimeters constraining the relationship:

- Counselor: Specifically trained to provide advice in an area.

- Sponsor: Invests in your success and vouches for you, oftentimes by leveraging social capital.

- Coach: Trains you for a specific skill.

- Guide: Shows a pathway for you to navigate.

- Connector: Uses a large social network to help you find mentors based on similar interests, experiences, or circumstances.

Structures, Pros and Cons of Mentorship

Mentorship has always been vital for aiding success. It is most essential when great uncertainties strike (e.g., the current pandemic, economic, and humanitarian crises) and our vision narrows to the immediate. Even the immediate may blur. The following are some popular structures, always used in some combination, to formulate the setting between mentors and mentees:

- Formal Mentoring: Individuals assigned to each other in accordance to an organization’s policies. It ensures members receive formal guidance and feedback but carries the risk of mere compliance (box checking), low motivation, and even resentment from involuntary mentors.

- Informal Mentoring: A volunteered relationship based on similar interests and compatibility. There is little to no power dynamics since the mentor has no supervisory or evaluative responsibilities over the mentee. There is a risk of trading objectiveness for favoritism when a friendship develops.

- Dyadic Mentoring: Relationship between one mentee and one mentor where the logistics and scope of interactions are typically their choice. While there is a high potential for honest and attentive discussions, there is also a risk of merely duplicating the mentor.

- Triad, Group, and Network Mentoring: Settings where multiple mentors/mentees discuss topics together while the mentee(s) learn and integrate the information on their own. This aids in aligning the intersections of multiple disparate skills and life situations, but there is a risk of peer pressure if mentors are homogenous and imply a sense of authority.

- Developmental and Career Mentoring: Long-term relationships during mentees’ developmental milestones or various stages of their careers. There is consistent advice that is well-informed of the mentees’ context but also the risk of becoming reliant on the mentor for direction, which stifles creativity and novel career paths.

- Reverse Mentoring: Older executives and personnel mentored by younger members on current trends, emerging topics, technology, and social media. Senior personnel stay applicable while the younger mentor becomes connected and invested to the organization. However, there is a risk of anxiety due to power dynamics and generational ideologies.

- Micro-Mentoring: Brief advice to specific questions through social media. It has the benefit of rapid and concise input from vast networks but also the potential for inconsistent or dishonest advice/feedback with ulterior motives.

- Peer-Based Mentoring: Similarly skilled members sharing current experiences and giving feedback. There is a direct ability to relate to issues, perceptions, and navigational barriers as well as the potential for confirmation bias, favoritism, and hidden competition.

- Situational Mentoring: A short-term relationship that focuses on coaching. There’s the benefit of a clear objective with a well-defined outcome. On the other hand, the mentoring is limited in scope and ability to address intersecting needs.

- Virtual Mentoring: Relationship held and maintained from differing locations. It’s logistically flexible and facilitates mentoring outside of the mentee’s organization but also carries the risk of sparse or untimely feedback.

The early career perspective on mentoring is a precarious position. Are you a mentor or a mentee? Do you know how to mentor and whether you are ready? Was I a good mentee? What does “a good mentee” even mean? You may feel moments of comfort along with a sense of self-confidence while at other times you feel uncertain and disoriented with the desire to call out for advice. The following tips may be useful when addressing these questions.

Tips for Being a Mentor

- Listen, Facilitate. Provide honest listening of your mentee’s situation and context, know when to validate their feelings by sharing relevant experiences during their journey, and give advice that they are in no way obliged or pressured to follow. Also, gain insights from you mentee’s experiences to improve yourself and relevancy of your advice. Mentors are innately part mentee in the relationship if you listen and follow up attentively.

- Avoid Microaggressions, Practice Microinterventions. We all have explicit and implicit biases. Moreover, we all have actions that negatively affect others without being aware. A mentor is a model of professionalism and humanity. Practice identifying common microaggressions. Practice microinterventions on yourself and others. Read Sue et al. (2019) and Sue (2010) to learn about microaggressions and interventions.

- Avoid Mentor Malpractice. There are active (hijacker, exploiter, possessor) and passive (bottleneck, country clubber, world traveler) types of mentor malpractices. Read Chopra et al. (2016) on how to diagnose and treat these malpractices.

- Be Aware of Potential Mentee Missteps. See “Tips for Being a Mentee” section below.

- Take Pride in Your Mentee’s Success. Some mentees will surpass you and go on to higher levels of skill or success. Be proud and humbled. Do not compete with them. Hope all your mentees will reach such an accomplishment. This is the greatest complement mentors can receive. In fact, great mentors help people who have already outgrown them continue to outgrow them even more. Mentoring is not about making mentees into you but about helping them be the best version of what they want.

Tips for Being a Mentee

- Integrate across Disparate Mentors and Yourself. Have many different types of mentors. Retain some mentors and change other frequently. Read Liénard et al. (2018) on how combining elements from multiple mentors of disparate skills/perspectives with your own strengths can lead to greater outcomes.

- Avoid Mentee Missteps. A changing world induces stress, and your reactions will affect the functionality of your mentorship. There are conflict averse (overcommitter, ghost, doormat) and confidence lacking (vampire, lone wolf, backstabber) types of mentee missteps. Read Vaughn et al. (2017) on how to diagnose and treat these missteps.

- Be Aware of Potential Mentor Misconduct. See “Tips for Being a Mentor” section above.

- Take Responsibility, Own Your Successes. All mentors are human, flawed, and have a different background that has molded their perception of the world. Your goal is not to become your mentor or role model—it is to become the best version of you. Your mentor helps you to discover your latent abilities and provides insights on various pathways you might journey.

- Actively Participate in the Process. Interpret, analyze, and contextualize your mentor’s advice. Is it relevant to your personal circumstances, career stage, and goals? Is it still relevant in today’s career environment? Then integrate the advice into the idiosyncrasies of your next steps. In doing so, you do not just become your mentor or what your mentor views you as, but you become a better version of yourself that you actively participated in and only you own.

Navigating Your Walls

Mentors help guide mentees beyond their invisible walls. Here, the wall is metaphorical and represents the unknown quantity of tasks or effort mentees can take on before progress stops. Pressing and banging against the wall is unproductive. However, knowing where it is located is of immense value. Most of us do not know precisely where our wall is because it shifts over time throughout our lives—intellectually, socially, physically, and interest wise. Knowing your indicators that the wall is “nearby” will serve you well. Great mentors help mentees see the indicator when the mentees do not sense it themselves.

Stepping out of our comfort zone is not the same as stepping up to the wall. It is more like finding a new path through the maze of walls. The existence of your wall does not imply it is the only direction to move forward in. Navigating outside of your comfort zone can trigger incredible creativity you never knew you had. New thoughts, opinions, and perspectives rush to the forefront of your mind during and after these uncomfortable situations. However, these only occur when you are not up against your wall and you have room to move.

Mentors can help give their perspective on where you are relative to your own personal wall if you have built a dual relationship with honesty, trust, and open communication. Nevertheless, mentors can never have an absolute picture of what mentees are enduring, thinking, and feeling to precisely assess where the mentees stand relative to their walls. Therefore, mentees have to not only listen to the advice, thoughts, and perspectives of their mentors, but they also have to place those inputs into the context of their own lives and perspectives to make the most use of them. Good mentees do not just listen and do. They listen, think, remold the advice, and then apply it in the way that best serves themselves and their goals.

We are all mentees throughout our lives in some area. You will always be a mentor to someone else too, whether you know it or not. This dual role of being both a mentor and mentee is a good thing and needed for society to progress forward beyond its walls.

Dig deeper

Chopra, V., Edelson, D.P., & Saint, S. (2016). Mentorship malpractice. Journal of the American Medical Association, 315(14), 1453–1454.

Liénard, J.F., Achakulvisut, T., Acuna, D.E., & David, S.V. (2018). Intellectual synthesis in mentorship determines success in academic careers. Nature Communications, 9, 4840.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2019. The science of effective mentorship in STEMM. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25568 [Free PDF download].

Sue, D.W. (2010). Microaggressions in everyday life: race, gender, and sexual orientation. Hoboken, NL: John Wiley & Sons.

Sue, D.W., Alsaidi, S., Awad, M., Glaeser, E., Calle, C.Z., & Mendez, N. (2019). Disarming racial microaggressions: microintervention strategies for targets, white allies, and bystanders. American Psychologist, 74(1), 128–142.

Vaughn, V., Sanjay, S., & Vineet, C. (2017). Mentee missteps: tales from the academic trenches. Journal of the American Medical Association, 317(5), 475–476.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.