Wheat streak mosaic virus: Good management can reduce your risks

Wheat streak is often a sporadic disease in the Northern Great Plains. It is vectored by a very small eriophyid mite, the wheat curl mite. Symptoms include stippling or streaking of leaves, stunting, and yellowing. In the spring, symptoms can be easily confused with nutrient deficiencies. This article dicusses disease identification and management.

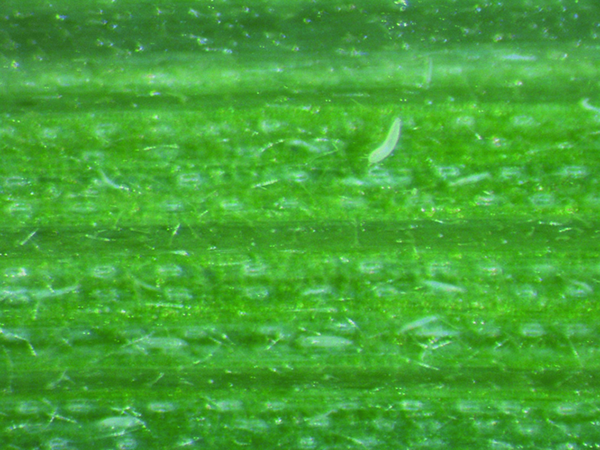

Wheat streak mosaic virus (WSMV) was first described in Illinois in 1919. Since that time, it has been found worldwide, occurring in a diversity of crops including wheat, barley, durum, corn, and many grassy weed species. It is vectored by a very small eriophyid mite, the wheat curl mite. Symptoms include stippling or streaking of leaves, stunting, and yellowing. In the spring, symptoms can be easily confused with nutrient deficiencies. However, nutrient deficiencies are generally consistent throughout a field, whereas WSMV is usually patchy and concentrated at field edges where the prevailing wind blew the vector into the field.

The mite and the virus depend on green, living plant material for their survival and reproduction. Management is primarily achieved by “eliminating the green bridge,” which means killing plants, particularly volunteer cereals, between harvest of an infected crop and the planting of the new crop. This can be accomplished with herbicides or tillage. Too often, environmental conditions make that goal difficult to attain.

The wheat curl mite causes the leaf to curl and provides a protective environment that shields the mite from stresses, including pesticide applications. There are no pesticides, known as miticides in this case, currently registered that have shown efficacy in managing wheat curl mites. In fact, some pesticides, such as insecticides, will kill a major predator of the wheat curl mite, thrips. Although thrips can also vector plant diseases and rise to damaging levels, some are predatory and can naturally control mite populations. When mites build to a sufficient population on a plant, they move to the top of the plant, stand up on their legs, and catch a downwind drift of air. If they find a suitable host plant, they will then continue reproducing. Triggers for mite movement can also include plant maturity and herbicide applications. Glyphosate application, in particular, has been shown to encourage mite movement as it takes plants several days to die, giving the mites a chance to move to the top of the plant and catch a downwind current.

Epidemics of WSMV are usually associated with widespread hail events near grain maturity. Hail results in a large number of volunteer plants that are difficult to control. Often, factors such as low grain prices, a reluctance or inability to invest in multiple herbicide applications, too much rain making field operations difficult, warm extended falls, or using volunteer seedlings as a “grazing opportunity” for cattle or other animals interferes with effective volunteer management. When conditions are favorable for disease spread, and wheat streak is known to be in the area, scouting and pro-active management of the green bridge are crucial.

Don’t Apply Additional Nitrogen if Mites Present

When symptoms of yellowing first occur in the spring, often the first reaction is to apply additional nitrogen to the plants. In the case of WSMV, however, nitrogen application will result in increased mite reproduction and spread of the virus. When the risk of disease is high, it is advised to inspect plants for mites or send them to a laboratory for testing prior to applying nitrogen. Any potential yield gains due to nitrogen application are generally lost due to the increase in virus infection of plants. In the Northern Great Plains, where spring and winter wheat plantings can overlap, early planted winter wheat next to late-harvested, infected spring wheat is a risk for WSMV. Spring wheat varieties are much more susceptible to the mite and virus than winter wheat. Malt and forage barley varieties are also susceptible, but yield effects are highly variable, making generalizations difficult.

There are some WSMV-resistant and WCM-resistant varieties available in southern states, but resistance genes confer a yield drag in the absence of the viral pathogen. The resistance genes currently deployed, Wsm1 and Wsm2, are temperature sensitive and do not work well at high temperatures. Wsm1 in winter wheat variety Mace provided cross resistance to Triticum mosaic virus (discussed below), but Wsm2 in variety Snowmass did not. A new gene for resistance, Wsm3, has been identified and is being incorporated into adapted germplasm. Resistant varieties are the best choice for disease management where risk of disease is high.

In addition to wheat streak, there are several other viruses in the disease complex to watch for. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, new viruses were identified that are also transmitted by the wheat curl mite, cause similar symptoms to WSMV, and cause greater yield losses when they co-occur with WSMV. These viruses are High Plains Wheat mosaic virus (HPWMoV) and Triticum mosaic virus (TriMV).

In the mid-2000s, a wheat virus survey was conducted in the Great Plains showing that HPWMoV and TriMV occurred from Montana to Texas. At that time, TriMV had been recently identified and was relatively rare in the Northern Great Plains states. During a WSMV epidemic in Montana in 2016, a population shift in the virus was found, where most plants were co-infected with at least two viruses (WSMV and TriMV). The reasons behind this population shift are not known.

With funding from the USDA-NIFA, Montana State University has been working on an online tool for predicting the risk of WSMV in the Northern Great Plains. This tool has been beta-tested with a number of groups and is available for further evaluation from other users. If you would like to interact with the tool to predict your own risk or use it as a tool with clients, please visit the current website at https://tim-msu-ecol.shinyapps.io/wsm_app/. Feedback can be sent to Send Message. It is anticipated that the tool will be made publicly available in collaboration with Kansas State University’s MyFields project (www.myfields.info) in the near future.

Wheat streak is often a sporadic disease in the Northern Great Plains, whereas in the southern states, is a more routine disease problem requiring close monitoring and management. Consultants and farmers should be able to discriminate between wheat streak and nutrient deficiencies or submit a sample for diagnosis. This disease can be difficult to control in years where hail is widespread and environmental conditions are favorable for disease development and spread. To manage the disease, eliminate the green bridge, do not fertilize infected plants, and use resistant varieties where appropriate. There are no pesticides available for management of the mite vector or the virus. In high-risk years, WSMV is a landscape-level problem, and it takes a dedicated community to clean up the entire area. In many cases, the right environmental conditions such as severe drought will reduce WSMV, but avoidance of an epidemic is preferred.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.