Iron availability and management considerations: A 4R approach

Though iron deficiency symptoms can be visually apparent in most crops, the underlying reasoning for reduced uptake or availability can be more complex. Dedicating time to understanding the soil-plant environment in each distinctive soil where you suspect iron to be limiting productivity is well worth it.

Iron (Fe) is a nutrient required by all organisms, including microbes, plants, animals, and humans. It was first recognized as a necessary plant nutrient in the mid-19th century when iron-deficient grapes were successfully treated with foliar applications of iron-bearing salts. Iron is a component of many vital plant enzymes and is required for a wide range of biological functions. As the fourth most common element in the earth’s crust, most soils contain abundant iron but in forms that are low in solubility and sometimes not readily available for plant uptake. The concepts of 4R Nutrient Stewardship—understanding how the right source of iron can be applied at the right rate with optimal timing and placement—can alleviate iron deficiencies.

Iron in Soils

Iron is abundant in many rocks and minerals, and as soils develop, there can be either enrichment or depletion of iron. Depletion commonly leads to deficiency, and enrichment can cause toxicity when potentially soluble iron minerals are high and in poorly drained soils. Iron concentration can be present at 50,000 times the crop’s annual demand, but factors that affect availability limit utilization. The main source of iron in soils for use by plants comes from secondary oxides absorbed or precipitated onto soil mineral particles and iron–organic matter complexes.

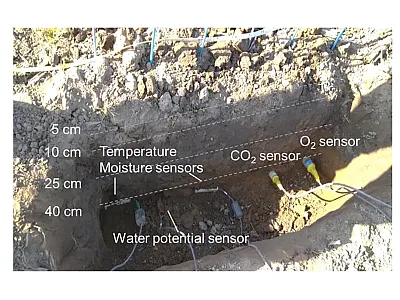

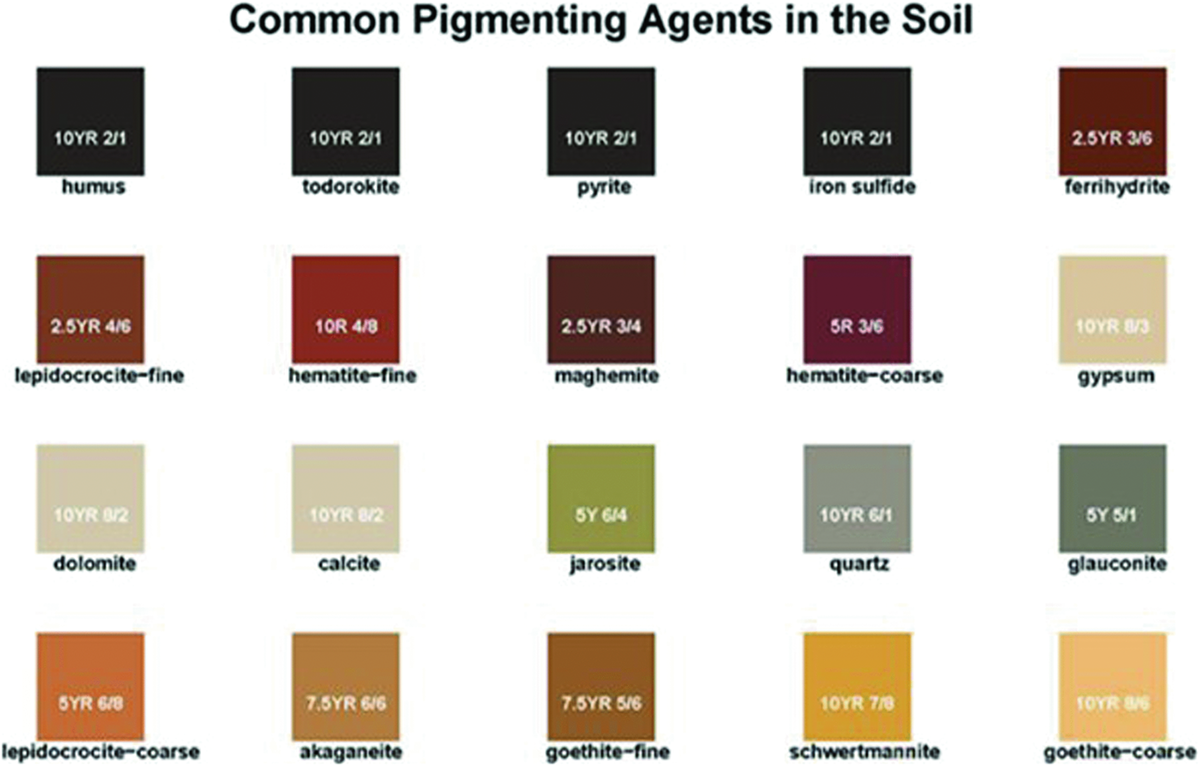

It is critical to consider that iron occurs in two oxidation states: reduced, as ferrous iron (Fe2+), or oxidized, as ferric iron (Fe3+). Soil pH and water-filled pore space will significantly affect the form of iron present. In aerated soils, iron is readily oxidized to its ferric state and forms a group of highly insoluble ferric oxides and hydroxide minerals, such as goethite (FeOOH) and hematite (Fe2O3) displayed in Figure 1. The presence of specific iron forms will affect the dominant soil color (Figure 1). Organic matter content (brown to black) and iron (yellow to red) presence have a tremendous influence on matrix soil color (Schwertmann, 1993; Schulze et al., 1993). When iron is reduced, or in Fe2+ form, gray color dominates the soil matrix, as is the case in many oversaturated or hydric soils. If adequate aeration has occurred, Fe2+ will lose electrons and exist as Fe3+ with the characteristic reddish hue.

Determining soil iron concentration is complicated, and multiple methods of soil iron analysis have been established depending on the use of the soil test results. The most widely used extraction procedure is the DTPA (diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid) method (Lindsay and Norvell, 1978). This method utilizes acid dissolution of iron-containing minerals and complexes and then chelates to iron in solution for quantification. Other methods that have been developed, but not adopted in more routine soil-testing programs, include magnesium chloride extraction and a buffered reaction that reduces iron in the soil sample and then chelates with the iron for analysis (Holmgren, 1967). A remaining challenge of determining the need for iron application or the rate to apply iron to a crop is that soil test iron has not been well correlated with crop yield or nutrient uptake. Currently, it is best used as an index for potentially bioavailable iron in the rooting zone.

Iron in Plants

In plants, iron plays an essential role in oxidation and reduction reactions, respiration, photosynthesis, and enzyme reactions. For example, iron is an important component of the enzymes used by nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Iron requirement, and thus uptake, is relatively low compared with other essential nutrients. Bender et al. (2015) reported 0.76 lb Fe/ac taken up by a soybean crop yielding approximately 52.5 bu/ac, and more than half of the iron was accumulated before seed filling. In corn, total plant iron uptake has been reported to be between 1.25 lb Fe/ac (Bender et al., 2013) and 1.74 lb Fe/ac in a 2000-era hybrid, which was measured at reproductive stage R6 (Woli et al., 2019).

Plant roots absorb iron from the soil solution most readily as (ferrous) Fe2+, but in some cases, also as (ferric) Fe3+ ions (Kobayashi and Nishizawa, 2012). Plants have developed clever methods of influencing rhizosphere conditions to obtain iron, and generally utilize two ways to access the Fe2+ or Fe3+ ions. The first strategy occurs in dicot species and non-grass monocot species where Fe3+ ions are reduced to Fe2+ ions before moving into the root across selective membranes (Marschner and Römheld, 1994). This process involves the root excreting a variety of organic compounds and acids into the soil and is employed by most fruit and tree crops. In the second strategy, roots of grass species acquire iron by excreting an organic chelate (siderophore) that solubilizes iron from the soil, allowing enhanced uptake, used by crops such as corn, sorghum, and wheat (Marschner and Römheld, 1994). Chelates are simply organic or synthetic chemical compounds with multiple sites to bond with metals, or in this case, iron.

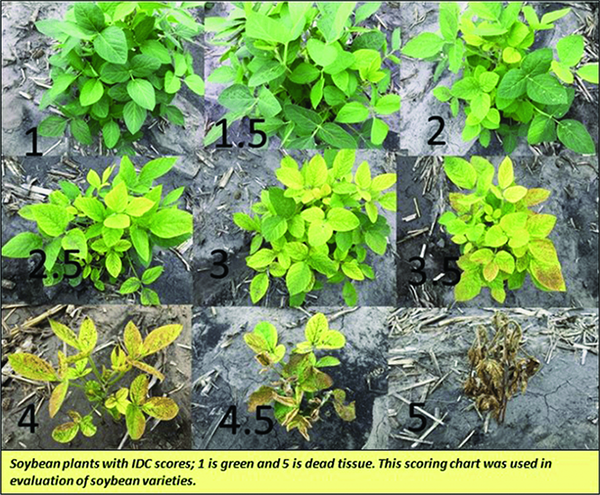

Iron deficiency symptoms have stark, defining characteristics and are similar across most crop species (Figures 2, 3, and 4). Immature iron-deficient leaves develop chlorosis (yellowing) between the leaf veins while the veins initially remain green. If the plant does not obtain iron, the symptoms become more severe, and the deficient leaves become pale yellow to white in color. Chlorophyll–protein complexes in the chloroplast require iron and the absence of usable iron perpetuated this condition. Young tissue displays deficiency symptoms first because iron is mostly immobile within plants. The severity of iron deficiency chlorosis (IDC) reflects the corresponding iron availability and plant utilization of each incidence. Iron soil chemistry can also have important effects on the availability of other plant-essential nutrients such as phosphorus (P). Iron and P will bond to form precipitates and secondary minerals like strengite (FePO4 • H2O) in acid and flooded conditions and reduce P availability.

Tissue analysis can be a useful tool for the comparison of plants with and without deficiency symptoms; however, contamination of samples is a major concern (Jones and Wallace, 1992). Rinsing or washing plant leaves prior to iron analysis has been shown to dramatically reduce the measured iron concentration (Jones and Wallace, 1992). Due to the lack of mobility of iron in plants, young tissue is commonly sampled to identify deficiencies. Mills and Jones, Jr. (1996) provide practical direction and information about tissue-sampling protocols for different crops. The iron concentration in plant leaf tissues varies between plant species, but it is generally between 50 and 250 ppm dried and ground (Vitosh et al., 1995). If the iron concentration is less than 50 ppm, there are usually signs of deficiency, and toxic effects may be observed when the concentration exceeds 500 ppm.

Availability and Deficiency Factors

Most soils contain adequate iron to meet crop demand for growth and development, but chemical and environmental factors reduce availability and result in inhibited plant uptake or utilization. When soils become saturated, Fe3+ is converted to Fe2+ by microbial action. The Fe2+ form is much more soluble and can result in toxicity for some rice varieties in flooded soils under strongly acidic conditions (Becker and Asch, 2005). Combinations of low soil pH (< 4.5) and reduced or flooded conditions should be monitored to prevent potential toxicity issues.

While iron deficiency has been reported in many crop species and environments, some specific crops show greater sensitivity to low available iron and warrant intensive study to mitigate yield losses. Soybean may be the most widely studied crop that exhibits iron deficiency yield limitations, which may reflect the increases of soybean acreage into regions with calcareous soil. Soybeans release chemicals from their roots to create a reducing condition and lower the local pH and transform Fe3+ in Fe(OH)3 to Fe2+ that can be utilized in metabolic functions.

Soil nitrate (NO3–) concentration has also shown a relationship with severity of IDC in soybean (Bloom et al., 2011). As NO3– is converted to ammonium (NH4+) in the leaf, the pH of intra-tissue sap will increase, causing Fe2+ to be oxidized to Fe3+ and become unavailable for use. Reduced soil and leaf NO3– may be a reason for the phenomenon of early-season soybean plants being greener in wheel tracks compared with those outside the tracks within the same field (Bloom et al., 2011).

Iron deficiency can cause significant economic losses in fruit crops as well, particularly when grown in calcareous soil. Similar to most crops, a symptom of iron deficiency in fruit and tree crops is chlorotic young tissue; however, additional effects on visible fruit quality have been observed (Àlvarez-Fernàndez et al., 2006). Fruit size and number of fruits per tree were affected by iron deficiency in a study conducted by Àlvarez-Fernàndez et al. (2003). Although commercially acceptable fruits harvested decreased, vitamin C concentration increased when deficiency symptoms were present.

Iron toxicity is relatively rare, but the symptoms include bronzed and striped leaves. These effects are the result of excess Fe-hydroxyl radicals disrupting cellular functions. Due to the importance of maintaining iron concentrations within safe ranges in plant tissues, the whole process of iron uptake into roots (i.e., the movement from roots to shoots and storage and release within plant cells) is highly regulated.

4R Management of Iron

While soil concentrations of iron tend to be high, the variability in availability can result in deficiency. Iron deficiencies are commonly observed in soils with pH >7.5, especially where there is abundant calcium carbonate (CaCO3 or lime). Iron solubility increases substantially as soil pH decreases. Calcareous soils can form bicarbonate (HCO3–) when they are saturated, and HCO3– interferes with iron uptake by plants (Alhendawi et al., 1997). This inhibition is usually only temporary, and iron deficiency symptoms disappear when the soil drains and warms up.

Using a 4R approach by considering the source, rate, timing, and placement of iron fertilization can compensate for iron deficiency. One part of an approach is to consider crop variety and tolerance to low iron availability. The second part is considering soil- or foliar-applied fertilizer applications to avoid or correct deficiency, or growers can work to attain soil conditions that foster greater crop availability of iron.

Large genetic differences exist among cultivars tolerant of low-iron conditions, and a variety change can be effective for dealing with challenging soil conditions (Goos and Johnson, 2000; Hansen et al., 2003; Cakmak et al., 2010). Local screenings of hybrids and varieties by universities and crop breeders can identify which lines perform the best in low-available-iron conditions (Figure 5). Grain and forage sorghum have frequently exhibited yield loss related to iron deficiency (Clark, 1982). In Kansas, Obour et al. (2019) screened 14 grain sorghum hybrids at three rates (0, 0.18, and 0.36 lb Fe/ac) of EDDHA-chelated Fe applied at planting. The greenhouse study used a silt loam soil with a pH of 7.9, 3.1% organic matter, and DTPA extractable 5.8 lb Fe/ac. They found considerable differences in hybrid susceptibility to IDC. Grain sorghum yield has been reported to be higher with application of chelated iron fertilizer compared with no iron applied in both greenhouse (Obour et al., 2019) and field studies (Clark et al., 1988). Assessing variability of low-available-iron conditions in a field helps to target where yield loss may be mitigated and where you should expect a crops response to fertilization or not.

Soybeans have exhibited reduced yield when they experience iron deficiency. Hansen et al. (2003) did a comprehensive assessment of soil properties and corresponding degrees of chlorosis in soybeans in western Minnesota. They confirmed the findings of a grower survey that reported 24% of soybean in the studied area displayed severe chlorosis and found significant soil predictors of chlorosis to be soluble salts, soil concentration of iron measured as DTPA-Fe, DTPA-chromium (Cr), and soil moisture content. Overall, considering both soil test DTPA-Fe and soluble salts (electrical conductivity) when screening varieties for chlorotic iron deficiency symptoms in the North-Central region was recommended (Hansen et al., 2003). This is consistent with other Minnesota research reporting that yield of iron-deficiency-susceptible varieties was correlated with soil pH, DTPA-Fe, electrical conductivity, and soil organic matter at a 6-inch depth (Kaiser et al., 2014). With such dynamic soil properties influencing iron availability, optimizing iron nutrition is difficult and, in most cases, utilizing practices that inform the 4Rs such as soil tests, plant analysis, and yield maps together when putting a plan together pays dividends.

The source and timing of iron fertilizer affects availability and yield and is apparent in iron recommendations (Shapiro et al., 2008). When inorganic iron fertilizers are added to soil (e.g., ferric sulfate, ferrous sulfate, ferrous ammonium phosphate, ferrous ammonium sulfate, and other iron-oxides), they are rapidly converted to insoluble forms and benefit plant nutrition if conditions allow. However, the timing of the availability of iron fertilizers can vary by source. Iron fertilizers protected with an organic chelate can be effectively applied to soils to correct plant deficiencies. Chelated fertilizers such as Fe-EDDHA (Kaiser et al., 2014; Gamble et al., 2014) have been used with reasonable effectiveness, but their cost may be prohibitive for whole-field applications. Gamble et al. (2014) found a soybean yield increase of 2.98 bu/ac across a multiyear study at two high-pH sites in Alabama. Foliar sprays containing iron salts or chelates are effective at correcting plant iron deficiencies during the growing season, but they may require repeated applications to prevent reoccurrence of deficiency.

Correcting any underlying soil problems, like drainage, preventing uptake of adequate iron is a long-term option. Additionally, achieving an optimal soil pH and soil structure and avoiding applications of competing cations can shift the availability of the iron in the soil or iron applied to the soil. Adding an acidifying material to soils with elevated pH to improve the solubility of iron is sound in theory; however, more popular methods of acidifying soils are expensive and require multiple years to see improvements. This acidification can be done for the entire field, or spot treatment of a portion of the root zone is often sufficient to improve iron availability in the right place. Companion crops have also been shown to be effective at reducing soil and tissue NO3– in soybean, lowering IDC severity, and increasing yield for IDC-susceptible varieties, but termination timing can provide management difficulties (Kaiser et al., 2014).

Key Takeaways

Though iron deficiency symptoms can be visually apparent in most crops, the underlying reasoning for reduced uptake or availability can be more complex. Dedicating time to understanding the soil-plant environment in each distinctive soil where you suspect iron to be limiting productivity is well worth it. Below are some questions to address if iron deficiency symptoms are appearing. If deficiency symptoms are apparent and economically viable options are available to correct them, creating an iron component in your 4R plant nutrition plan may be warranted.

- Are there known drainage or aeration issues that may restrict ideal root zone conditions?

- Have recent soil samples indicated high-pH values or concentrations of calcium carbonates?

- Does the crop in question have any documented issues with or susceptibilities to iron deficiencies?

- Where would iron fertilization fit into my management program if needed? And would the product need to be soil- or foliar-applied?

Alhendawi, R.A., Römheld, V., Kirkby, E.A., & Marschner, H. (1997). Influence of increasing bicarbonate concentrations on plant growth, organic acid accumulation in roots and iron uptake by barley, sorghum, and maize. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 20(12), 1731–1753. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904169709365371

Àlvarez-Fernàndez, A., Abadía, J., & Abadía, A. (2006). Iron deficiency, fruit yield and fruit quality. In Iron nutrition in plants and rhizospheric microorganisms (pp. 85–101). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Álvarez-Fernández, A., Paniagua, P., Abadía, J., & Abadía, A. (2003). Effects of Fe deficiency chlorosis on yield and fruit quality in peach (Prunus persica L. Batsch). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 51(19), 5738–5744. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf034402c

Becker, M., & Asch, F. (2005). Iron toxicity in rice—conditions and management concepts. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 168(4), 558–573. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.200520504

Bender, R.R., Haegele, J.W., & Below, F.E. (2015). Nutrient uptake, partitioning, and remobilization in modern soybean varieties. Agronomy Journal, 107(2), 563–573. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj14.0435

Bender, R.R., Haegele, J.W., Ruffo, M.L., & Below, F.E. (2013). Nutrient uptake, partitioning, and remobilization in modern, transgenic insect-protected maize hybrids. Agronomy Journal, 105(1), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2012.0352

Bloom, P.R., Rehm, G.W., Lamb, J.A., & Scobbie, A.J. (2011). Soil nitrate is a causative factor in iron deficiency chlorosis in soybeans. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 75(6), 2233–2241. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2010.0391

Cakmak, I., Pfeiffer, W.H., & McClafferty, B. (2010). Biofortification of durum wheat with zinc and iron. Cereal Chemistry, 87(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1094/CCHEM-87-1-0010

Clark, R.B. (1982). Iron deficiency in plants grown in the Great Plains of the U.S. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 5(4–7), 251–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904168209362955

Clark, R.B., Williams, E.P., Ross, W.M., Herron, G.M., & Witt, M.D. (1988). Effect of iron deficiency chlorosis on growth and yield component traits of sorghum. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 11(6–11), 747–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904168809363839

Gamble, A. V., Howe, J. A., Delaney, D., van Santen, E., & Yates, R. (2014). Iron chelates alleviate iron chlorosis in soybean on high pH soils. Agronomy Journal, 106(4), 1251–1257. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj13.0474

Goos, R.J., & Johnson, B.E. (2000). A comparison of three methods for reducing iron-deficiency chlorosis in soybean. Agronomy Journal, 92(6), 1135–1139. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2000.9261135x

Hansen, N.C., Schmitt, M.A., Andersen, J.E., & Strock, J.S. (2003). Iron deficiency of soybean in the Upper Midwest and associated soil properties. Agronomy Journal, 95(6), 1595–1601. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2003.1595

Holmgren, G.G.S. (1967). A rapid citrate-dithionite extractable iron procedure. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 31(2), 210–211.

Jones, J.B., & Wallace, A. (1992). Sample preparation and determination of iron in plant tissue samples. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 15(10), 2085–2108. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904169209364460

Kaiser, D.E., Lamb, J.A., Bloom, P.R., & Hernandez, J.A. (2014). Comparison of field management strategies for preventing iron deficiency chlorosis in soybean. Agronomy Journal, 106(6), 1963–1974. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj13.0296

Kobayashi, T., & Nishizawa, N.K. (2012). Iron uptake, translocation, and regulation in higher plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 63(1), 131–152. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105522

Obour, A., Schlegel, A., Perumal, R., Holman, J., & Ruiz Diaz, D. (2019). Evaluating grain sorghum hybrids for tolerance to iron chlorosis. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 42(4), 401–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904167.2018.1549677

Lindsay, W.L., & Norvell, W.A. (1978). Development of a DTPA soil test for zinc, iron, manganese, and copper. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 42, 421–428. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1978.03615995004200030009x

Marschner, H., & Römheld, V. (1994). Strategies of plants for acquisition of iron. Plant and Soil, 165(2), 261–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00008069

Mills, H.A., and Jones Jr., J.B. (1996). Plant analysis handbook II. A practical sampling, preparation, analysis, and interpretation guide. Athens, GA: Micro-Macro Publishing.

Schulze, D.G., Nagel, J.L., Van Scoyoc, G.E., Henderson, T.L., Baumgardner, M.F., & Stott, D.E. (1993). Significance of organic matter in determining soil colors. In J.M. Bigham and E.J. Ciolkosz (Eds.), Soil color (SSSA Spec. Publ. 31; pp. 71–90). Madison, WI: SSSA. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaspecpub31.c5

Schwertmann, U. (1993). Relations between iron oxides, soil color, and soil formation. In J.M. Bigham and E.J. Ciolkosz (Eds.), Soil color (SSSA Spec. Publ. 31; pp. 51–69). Madison, WI: SSSA. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaspecpub31.c4

Shapiro, C.A., Ferguson, R.B., Hergert, G.W., Dobermann, A., and Wortmann, C.S., (2008). Fertilizer suggestions for corn. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Extension.

Woli, K.P., Sawyer, J.E., Boyer, M.J., Abendroth, L.J., & Elmore, R.W. (2019). Corn era hybrid nutrient concentration and accumulation of secondary and micronutrients. Agronomy Journal, 111(4), 1604–1619. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2018.09.0621

Ansyar Tambara, Fahruddin Fahruddin, Baharuddin Patandjengi, Effect of iron (Fe) concentration on rice field sustainability and paddy growth in Pesouha Village, Pomalaa District, Kolaka Regency, IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 10.1088/1755-1315/1557/1/012017, 1557, 1, (012017), (2025).

P. Kamarudheen, M. R. Mayadevi, J. K. Smitha, V. I. Beena, P. Jayasree, S. Sandeep, K. Archana, J. S. Aryadevi, Iron-acidity interactions in hydromorphic rice systems of south western coastal India, Discover Soil, 10.1007/s44378-025-00110-y, 2, 1, (2025).

Haochen Zhao, Onusha Sharmita, Abu Bakar Siddique, Sergey Shabala, Meixue Zhou, Chenchen Zhao, Optimizing Nitrogen Supplementation: Timing Strategies to Mitigate Waterlogging Stress in Winter- and Spring-Type Canola, Plants, 10.3390/plants14172641, 14, 17, (2641), (2025).

Nikoleta Kircheva, Silvia Angelova, Valya Nikolova, Todor Dudev, The Role of Axial Ligand in Determining the Mg 2+ /TM 2+ (TM = Fe, Mn, Cu, Zn) Selectivity in Chlorophyll , The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5c00243, 129, 20, (4929-4937), (2025).

Mirosław Wyszkowski, Natalia Kordala, The Role of Organic Materials in Shaping the Content of Trace Elements in Iron-Contaminated Soil, Materials, 10.3390/ma18071522, 18, 7, (1522), (2025).

Khadija Zahidi, Latifa Mouhir, Abdelaziz Madinzi, Safaa Khattabi Rifi, Salah Souabi, Impact of industrial emissions on soil contamination: the case of Mohammedia soil, Morocco, Euro-Mediterranean Journal for Environmental Integration, 10.1007/s41207-025-00762-w, 10, 4, (2679-2702), (2025).

Martina Haas, Katarína Tomíková, Marián Janiga, Aibek Abduakassov, Zuzana Kompišová Ballová, Indication of air pollution based on the comparison of mercury and other elements in the faeces of marmots from the Western Carpathians and the Dzungarian Alatau, Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 10.1007/s11356-025-35902-w, 32, 7, (3617-3628), (2025).

Isidora Radulov, Adina Berbecea, Nutrient Management for Sustainable Soil Fertility, Sustainable Agroecosystems - Principles and Practices, 10.5772/intechopen.1006692, (2024).

Tatum Simms, Kristofor R. Brye, Trenton L. Roberts, Lauren F. Greenlee, Soil profile distribution of nutrients in contrasting soils amended with struvite and other conventional phosphorus fertilizers, Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment, 10.1002/agg2.20524, 7, 2, (2024).

Ahmad Ali, Rabia Amir, Alvina Gul, Faiza Munir, Kainat Ahmad, Anum Akram, Genomic engineering in peanut, Targeted Genome Engineering via CRISPR/ Cas9 in Plants, 10.1016/B978-0-443-26614-0.00018-7, (159-175), (2024).

Dawid Skrzypczak, Krzysztof Trzaska, Małgorzata Mironiuk, Katarzyna Mikula, Grzegorz Izydorczyk, Xymena Polomska, Jerzy Wiśniewski, Karolina Mielko, Konstantinos Moustakas, Katarzyna Chojnacka, Recent innovations in fertilization with treated digestate from food waste to recover nutrients for arid agricultural fields, Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 10.1007/s11356-023-31211-2, 31, 29, (41563-41585), (2023).

Shraddha Shirsat, Suthindhiran K, Iron oxide nanoparticles as iron micronutrient fertilizer—Opportunities and limitations, Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 10.1002/jpln.202300203, 187, 5, (565-588), (2023).

Elena Rosa-Núñez, Carlos Echavarri-Erasun, Alejandro M. Armas, Viviana Escudero, César Poza-Carrión, Luis M. Rubio, Manuel González-Guerrero, Iron Homeostasis in Azotobacter vinelandii, Biology, 10.3390/biology12111423, 12, 11, (1423), (2023).

Chance Bahati Bukomarhe, Paul Kitenge Kimwemwe, Stephen Mwangi Githiri, Edward George Mamati, Wilson Kimani, Collins Mutai, Fredrick Nganga, Paul-Martin Dontsop Nguezet, Jacob Mignouna, René Mushizi Civava, Mamadou Fofana, Association Mapping of Candidate Genes Associated with Iron and Zinc Content in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Grains, Genes, 10.3390/genes14091815, 14, 9, (1815), (2023).

E. L. C. Inovejas, A. F. Waje, Ch. O. Llait, T. J. Bajas, Delineation of Micronutrient Deficient Zones in Agricultural Soils of Santa Ignacia, Tarlac, Eurasian Soil Science, 10.1134/S1064229323600719, 56, 11, (1776-1783), (2023).

Miebaka Beverly Otobo, Christian Obi Nwaokezi, Iyingiala Austin-Asomeji, Israel Moses Israel, Tamuno-Boma Odinga, Assessment of Soil and Vernonia amygdalina Cultivated in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, Singapore Journal of Scientific Research, 10.3923/sjsr.2023.60.68, 13, 1, (60-68), (2023).

Helga Zelenyánszki, Ádám Solti, Functional Analysis of Chloroplast Iron Uptake and Homeostasis, Plant Iron Homeostasis, 10.1007/978-1-0716-3183-6_12, (147-171), (2023).

Camila Vanessa Buturi, Leo Sabatino, Rosario Paolo Mauro, Eloy Navarro-León, Begoña Blasco, Cherubino Leonardi, Francesco Giuffrida, Iron Biofortification of Greenhouse Soilless Lettuce: An Effective Agronomic Tool to Improve the Dietary Mineral Intake, Agronomy, 10.3390/agronomy12081793, 12, 8, (1793), (2022).

B. Duralija, D. Mikec, S. Jurić, B. Lazarević, L. Maslov Bandić, K. Vlahoviček-Kahlina, M. Vinceković, Strawberry fruit quality with the increased iron application, Acta Horticulturae, 10.17660/ActaHortic.2021.1309.146, 1309, (1033-1040), (2021).

Daniel Tran, Cédric Camps, Early Diagnosis of Iron Deficiency in Commercial Tomato Crop Using Electrical Signals, Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 10.3389/fsufs.2021.631529, 5, (2021).

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.