Tree-to-tree nutrient variability in pecan orchards

Tree-to-tree uniformity is desirable for nutrient management in orchards, particularly with the prevalence of nutrient application via fertigation, which makes it very difficult to tailor nutrient distribution for individual trees. The goals of this study were to measure the degree of variability of foliar nutrient concentrations exhibited by pecan trees in an Arizona orchard as well as to determine the importance of different sources of variation.

Tree-to-tree uniformity is desirable for nutrient management in orchards, particularly with the prevalence of nutrient application via fertigation, which makes it very difficult to tailor nutrient distribution for individual trees. Fertigation through drip or sprinkler irrigation systems is generally restricted to a single-rate, uniform nutrient distribution across the irrigated orchard block.

In practice, therefore, fertilizer applications are usually targeted to orchard blocks rather than individual trees. Processes for selecting appropriate fertilization targets may not be obvious and can be affected by the level of variability inherent in an orchard block. In a hypothetical orchard block with no variability, the average tree nutrient demand would be equal to the nutrient demand of each individual tree, but real orchards do exhibit considerable tree-to-tree variability. Variability may result from differences in soil properties; microclimate variations; irregular weed, disease, or insect pest pressures; non-uniform irrigation and fertilizer distribution; and genetic variability. Genetic variability in orchards is often minimized by the use of cloned root stocks and scions. Orchard species that are not commercially cloned are likely to exhibit greater genetic variability than cloned species. Pecan [Carya illinoinensis (Wangenh.) K. Koch] scions of named cultivars are typically grafted onto open-pollinated root stocks of known maternal parentage, but the variability of these half-siblings can be large. Orchard variability is likely a combination of all of these sources.

In previous studies (Heerema et al., 2017), we determined that photosynthesis rates of individual pecan trees declined when foliar zinc concentrations were below approximately 14 ppm and did not increase when foliar zinc concentrations were elevated above 14 to 22 ppm, establishing this range as a reasonable minimum foliar zinc target. These findings agree with those of Hu and Sparks (1991) who observed declines in photosynthesis rate when pecan leaf zinc concentrations were below 14 ppm. It is notable that these values are far below currently recommended minimum leaf zinc levels for commercial pecan production of 40 to 50 ppm (Heerema, 2013; Jones et al., 1991; Pond et al., 2006; Sparks, 1993).

Individual Tree vs. Block-Scale Measurements

What is the reason for this large discrepancy? In part, these differences reflect different targets. Whereas individual trees exhibit diminished photosynthesis rates associated with foliar zinc levels below 14 to 22 ppm, a reasonable orchard block minimum target must be greater, owing to tree-to-tree variability. A higher target (such as the frequently cited 40 to 50 ppm zinc minimum for pecans) may be a reasonable orchard block target to ensure that trees with the lowest foliar zinc concentrations within a block are not restricted by lack of zinc. This is an important consideration when applying individual tree response data such as those reported by Heerema et al (2017) to whole-orchard blocks. In contrast to orchard-wide measurements of nut yield and quality or tree growth rates, physiological measurements such as photosynthesis rate conducted on individual trees can provide very sensitive measurements of tree performance. It is therefore desirable to convert these individual tree data to pecan orchard management blocks.

Individual tree data arise from coupled physiological measurements (such as photosynthesis rate) and leaf analyses conducted on individual trees, resulting in pairs of single-tree nutrient concentrations and physiological parameters. Field- or block-scale measurements, on the other hand, consist of yield or other measurements collected from a group of trees, which are coupled with composite leaf samples collected from that group of trees.

Field-scale measurements of nutrient response from multiple trees (entire orchard blocks, rows, or groups of rows) can be directly applied to orchard blocks because composite leaf samples collected from multiple trees within the treatment area provide average nutrient concentrations for that group of trees. For example, Sparks (1993) combined vegetative growth and nut yield data collected from field studies conducted in several locations to develop a 50 ppm minimum leaf zinc threshold from pecan orchards. Because these response data already account for tree-to-tree variability, this value can be directly applied to whole-orchard blocks. In other words, a study that evaluates response on an orchard-block basis will inherently identify average nutrient concentrations associated with tree responses.

Typical leaf-sampling protocols recommend collecting leaves from numerous trees within a sampled area, which are combined into a composite sample for analysis (Heerema, 2013). Composite sampling measures average nutrient concentrations for the sampled area but does not provide estimates of variability statistics or identify minimum or maximum nutrient concentrations. Development of orchard block standards based on individual tree data and applied to averaged nutrient levels will depend on the degree of tree-to-tree variability exhibited within a block. It is therefore necessary to understand the extent of tree-to-tree variability within pecan orchards.

2018 Pecan Orchard Study

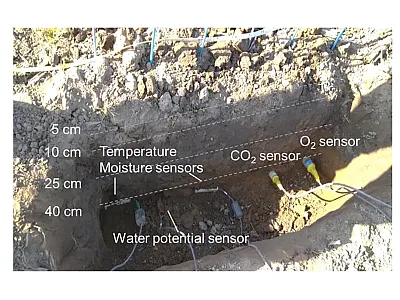

To that end, in 2018, we began a study in a commercial microsprinkler-irrigated pecan orchard in southeastern Arizona. The selected orchard block appeared to be very uniform with the exception of a few replanted trees that were slightly younger than the original plantings. The orchard block was established in 2011 with trees grafted on rootstock of the cultivar Ideal (also known as Bradley). The primary scion cultivar is Wichita, and every fifth row consists of Western (also known as Western Schley) pollinizers. Trees are planted in a 20- by 39-ft spacing. All trees have received identical management. In 2018, 6.0 lb/ac zinc in the form of Zn-EDTA was injected into the irrigation system in three separate in-season applications. No zinc was foliar-applied.

In each of seven contiguous rows (six Wichita and one Western row), 17 adjacent trees were selected for sampling. Foliar samples were collected from each of the 119 trees in this area on July 18, 2018. Samples were collected according to standard sampling protocol (Heerema, 2013). Samples were collected only from fruiting branches. Leaves were thoroughly washed, dried, and analyzed for nutrient concentrations. Soil below each tree was individually sampled in February 2019 and analyzed to determine available nutrient levels, pH, salinity, sodicity, and cation exchange capacity. The goals of this study were to measure the degree of variability of foliar nutrient concentrations exhibited by these trees as well as to determine the importance of different sources of variation. This discussion will focus solely on the degree of observed variability of foliar zinc concentrations.

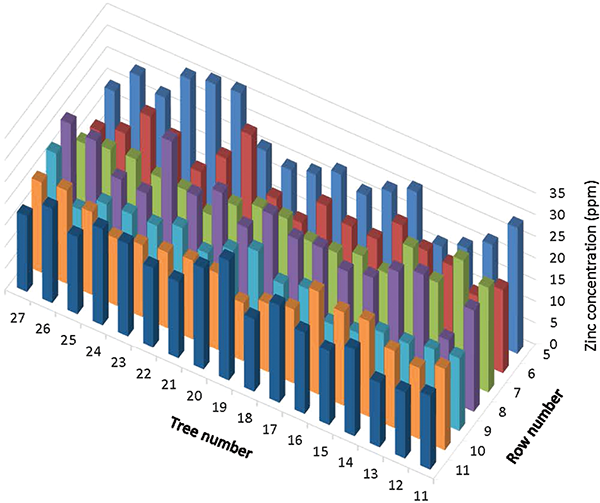

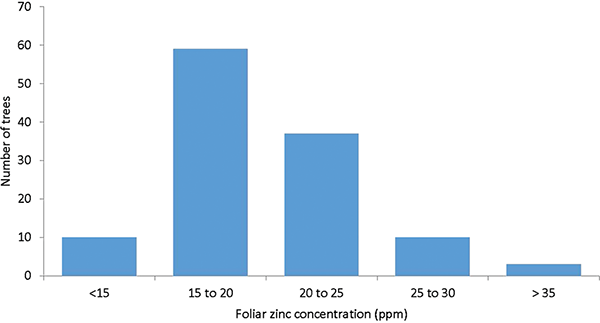

Leaf zinc concentrations within the sampled area exhibited a high degree of variability (Figure 1). The average of the measured foliar zinc concentrations was 19.9 ppm. Within the sampled area, the lowest measured foliar zinc concentration was 11.9 ppm, and the highest was 31.9 ppm. Ten individuals (8.4% of the trees) contained less than 15 ppm (Figure 2). Only 57 of the sampled trees contained in excess of 20 ppm of zinc. None of the trees reached recommended orchard foliar zinc levels of 40 to 50 ppm. Visible zinc deficiency symptoms were nearly absent in the sampled area and considered normal for well-managed orchards in the area (some minor zinc deficiency is almost always visible in local pecan orchards).

Although the average of measured zinc concentrations within the sampled area (19.9 ppm) exceeded the minimum level known to limit photosynthesis (about 15 ppm), some trees were well below this limit. Photosynthesis rate, vegetative growth, and nut production of the trees containing lower levels of zinc are potentially limited by lack of zinc. It is desirable to manage zinc such that trees in each orchard block with the lowest concentrations exceed a minimal acceptable zinc level. Because it is not practical or economically feasible to sample each tree individually, it is necessary to establish orchard-wide minimum nutrient concentration recommendations. We propose to do this by using estimates of tree-to-tree variability to convert individual tree response data into commercially applicable orchard standards.

Utilizing statistical variability parameters from our 2018 data, we have attempted to determine the minimum average foliar zinc concentration that would ensure that most or all individual trees contain at least 15 ppm. Preliminary analyses indicate that an orchard block average of approximately 24 to 27 ppm (depending on the specific statistical interpretation methods used) would result in no more than 1% of trees containing less than 15 ppm foliar zinc. Additional data are needed to verify the acceptable average foliar zinc concentration for a pecan orchard block. To this end, the study was repeated in 2019.

Unrealistically High Pecan Foliar Zinc Standard?

There is a considerable difference between the 24 to 27 ppm threshold identified in the current work versus the 40 to 50 ppm commercial standard. Reasons for the higher commercial standard include lack of resolution in orchard-scale field data and the regression models used to relate foliar zinc concentration to pecan growth and nut yield that make precise threshold identification very difficult. Additionally, most pecan zinc response studies rely on foliar zinc applications that can result in contamination of leaf samples with residual foliar fertilizer. The combination of these effects may be an unrealistically high pecan foliar zinc standard of 40 to 50 ppm. Standards developed from more precise physiological measurements may be more accurate although thorough field validation is needed.

This strategy could be adopted for other nutrients for which physiologically derived nutrient concentration minima based on individual tree data are available. For example, Sherman et al. (2017) determined that the leaf tissue manganese concentration needed to maximize photosynthesis rates in immature pecan trees was approximately 152 ppm. Similarly, Heerema et al. (2014) estimated that pecan tree photosynthesis was maximized when foliar nitrogen concentrations exceeded 3.1%. Knowledge of manganese and nitrogen distributions in pecan orchards could be applied to convert these individual tree thresholds into values that can be applied to averaged orchard block nutrient concentrations. This approach could also be used to develop orchard-scale recommendations from precise individual tree measurements made in controlled environments such as greenhouses or growth chambers.

It is important to recognize the difference between nutrient concentration optima based on research data relating nutrient concentrations to single-tree physiological measurements versus the orchard-block average nutrient concentrations that form the basis of commercial fertilizer recommendations. Single-tree measurements can be more precise and repeatable than orchard-block-scale measurements but do not yield information that is directly applicable in commercial orchard management. Measurements of tree-to-tree variability can be used to “convert” individual tree data into usable nutrient recommendations.

Acknowledgements

This research was partially funded by the Arizona Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Block Grant Program. Research reported in this article was conducted in Farmers Investment Company pecan orchards with support and assistance from Farmers Investment Company.

Dig deeper

Heerema, R. 2013. Diagnosing nutrient disorders of New Mexico pecan trees. New Mexico State University Extension Guide H-658. http://aces.nmsu.edu/pubs/_h/H658.pdf

Heerema, R.J., VanLeeuwen, D., St. Hilaire, R., Gutschick, V.P., & Cook, B. (2014). Leaf photosynthesis in nitrogen-starved ‘Western’ pecan is lower on fruiting shoots than non-fruiting shoots during kernel fill. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science139(3), 267–274. https://doi.org/10.21273/JASHS.139.3.267

Heerema, R.J., VanLeeuwen, D., Thompson, M.Y., Sherman, J.D., Comeau, M.J., & Walworth, J.L. (2017). Soil-application of zinc-EDTA increases leaf photosynthesis of immature ‘Wichita’ pecan trees. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science142(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.21273/JASHS03938-16

Hu, H., & Sparks, D. (1991). Zinc deficiency inhibits chlorophyll synthesis and gas exchange in ‘Stuart’ pecan. Hortscience26(3), 267–268. https://doi.org/10.21273/hortsci.26.3.267

Jones, J.B. Jr., Wolf, B., and Mills, H.A. (1991). Plant analysis handbook. Athens, GA: Micro-Macro Publishing, Inc.

Pond, A.P., Walworth, J.L., Kilby, M.W., Gibson, R.D., Call, R.E., & Nuñez, H. (2006). Leaf nutrient levels for pecans. HortScience41(5), 1339–1341. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.41.5.1339

Sparks, D. 1993. Threshold leaf levels of zinc that influence nut yield and vegetative growth in pecan. HortScience28(11), 1100–1102.

Walworth, J.L., White, S.A., Comeau, M.J., & Heerema, R.J. (2017). Soil-applied ZnEDTA: Vegetative growth, nut production, and nutrient acquisition of immature pecan trees grown in an alkaline, calcareous soil. HortScience52(2), 301–305. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI11467-16

Sherman, J., VanLeeuwen, R.J.D., and St. Hilaire, R. (2017). Optimal manganese nutrition increases photosynthesis of immature pecan trees. HortScience52(4), 634–640. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI11252-16

Xinwang Wang, Keith Kubenka, Warren Chatwin, Angelyn Hilton, Braden Tondre, Tingying Xu, Lu Zhang, Rootstock impacts on ‘USDA-ARS-Pawnee’ pecan growth, physiological traits, and soil microbial communities, Frontiers in Horticulture, 10.3389/fhort.2025.1603031, 4, (2025).

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.