Nitrogen availability from cover crops: Is it always about the C:N ratio?

The commonly accepted belief of crop and soil scientists and practitioners is that the tie-up or release of N from cover crops is based largely on carbon-to-nitrogen ratios (C:N). Recent research in Wisconsin and North Dakota challenge this long-held belief.

The commonly accepted belief of crop and soil scientists and practitioners is that the tie-up or release of N from cover crops is based largely on carbon-to-nitrogen ratios (C:N). Generally, the reasoning is that if cover crop dry matter has a C:N ratio greater than 30, N tie-up is likely, and if the ratio is less than 20, release of N is likely. When the C:N ratio is between 20 and 30, we assume neither N tie-up or release will occur. Recent research in Wisconsin and North Dakota challenge this long-held belief. In this article, we will highlight this research, which demonstrates that not all low C:N ratio cover crops or mixtures lead to more N availability to the subsequent crop.

Clover and Radish in Wisconsin

Opportunities for successful cover crop establishment occur when cover crops can be planted in late summer following winter wheat harvest in the upper Midwest. In addition, there is more opportunity for different cover crop species to be planted, especially green manure cover crops that will supply N to the next year's corn crop (and result in less commercial N needed for optimal production). Two popular cover crops that can be planted after winter wheat harvest are radish and crimson clover. Radish is a brassica that can be drilled at a rate of 10 lb/ac and will winter-kill. Several years of research trials have been conducted in Wisconsin to evaluate whether radish will supply N to the subsequent corn crop. Radish was evaluated across three locations and three years in Wisconsin. The C:N ratio of total radish biomass (above- and belowground biomass) ranged from 10 to 19, and the total N uptake ranged from 20 to 200 lb N/ac. While it would be expected this C:N ratio and the often large amounts of N contained in the radish biomass would be advantageous and lead to a reduction in the optimum N rate for the subsequent corn crop, we never determined a “N credit” resulting from the radish (Ruark et al., 2018).

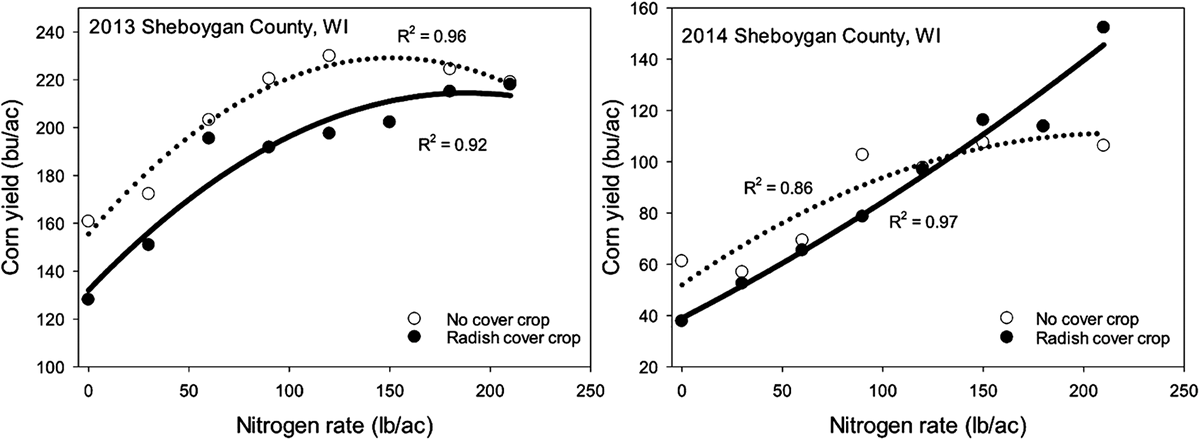

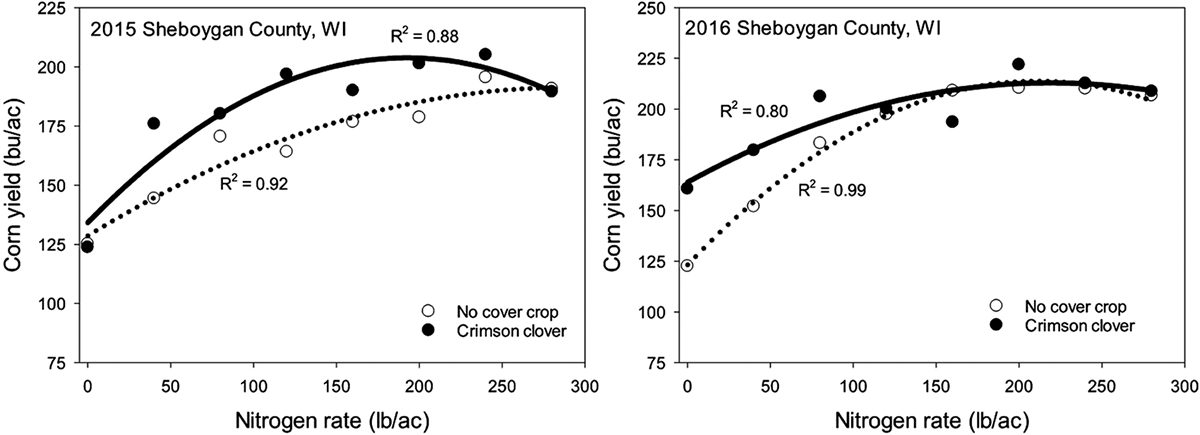

Figure 1 shows the effect of radish across two different growing seasons in Sheboygan, WI (located in northeast Wisconsin). In 2013, corn following radish appeared to require more N to optimize yield than following no cover crop. In 2014, lack of rainfall suppressed yields, but corn following radish outyielded corn following no cover crop at the higher N rates. In neither case did the radish appear to supply N. In these climates, radish decomposed quickly when the soils warmed up in the spring. The N trapped in the biomass is released quickly—perhaps too quickly—and does not remain available in the surface soil for the corn crop (although actual fate of this N remains unknown). It should be noted that we never saw a negative effect of the radish on corn yield and twice saw slight yield increases (although more N was required to achieve the increase in yield). Thus, while there may be some benefits to radish as a cover crop, there is no evidence that it will supply N to corn, and farmers should not alter their N applications.

Crimson clover is a nitrogen-fixing legume that can be drill-seeded at 15 lb/ac and will winter-kill in Wisconsin. In contrast to radish, crimson clover has been shown to clearly supply N to the next crop. Research trials were also conducted in Sheboygan County, WI to determine the potential N supply from this legume cover crop. Crimson clover was planted after winter wheat harvest in early- to mid-August and corn was planted the following spring. In 2015, crimson clover had a C:N ratio of 16:1 and had 45 lb/ac of N in the aboveground biomass; in 2016, even more biomass was produced (70 lb N/ac) and had a C:N ratio of 11:1. Nitrogen response studies demonstrated that clover supplied N to the corn as evidenced by greater yields at lower N rates (Figure 2). Maximum yields were relatively unaffected, but corn following no cover crop required more N to achieve maximum yield compared with following crimson clover. These results are quite typical across a range of clover cover crops (e.g., red clover and berseem clover) (Stute & Posner, 1995; Gentry et al., 2013).

Cover Crop Mixtures in North Dakota

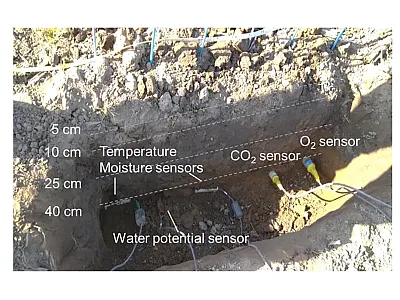

In North Dakota, a nitrogen response trial was conducted to determine if diverse and intensive cover cropping would supply N to the next season's corn crop. The research site was located southwest of Rutland, ND, a couple miles north of the North Dakota–South Dakota border. The study was conducted on a farmer field. In early August 2016, a cover crop mixture was seeded into winter wheat stubble in a long-term no-till field (>30 years continuous no-till). The mixture included field pea, flax, forage radish, and volunteer winter wheat. The entire field was planted with cover crops, and after emergence, replicated treatment strips (with and without cover crops) were created by spraying out cover crops about two weeks after planting. The cover crop biomass, residual soil nitrate N to 2 ft in depth, and soil moisture were sampled in the fall before freezing conditions (which caused winterkill of all covers except for winter wheat, which was sprayed out in the spring by the farmer) (Tables 1 and 2). In the spring, N rates at 40 lb/ac increments from 0 to 200 were applied as ammonium nitrate to the soil surface two days after corn planting.

Table 1. Individual cover crop species biomass and C:N ratio and total biomass and weighted C:N ratio of the cover crop mixture sampled on Oct. 21, 2016 at Rutland, ND

| Cover crop | Biomass (lb/ac) | C:N ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Field pea | 1,490 | 18.1 |

| Radish top | 1,690 | 15.4 |

| Radish root | 1,370 | 29.8 |

| Flax | 200 | 21.0 |

| Winter wheat | 220 | 14.5 |

| Total/weighted mean | 4,970 | 18.0 |

Table 2. Residual nitrate N and volumetric soil water content in cover crop and no-cover-crop main plots, winter wheat stubble, Rutland, ND, October, 2016

| Treatment | Residual soil nitrate-N in 2-ft depth (lb N/ac) | Volumetric water content (in water/2 ft of soil) |

|---|---|---|

| Cover crop | 15 | 5.05 |

| No-cover crop | 114 | 5.25 |

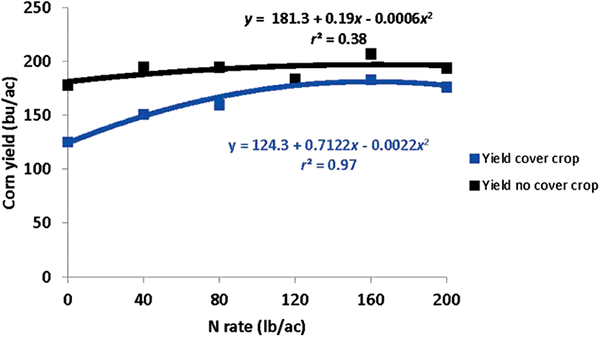

The total N in the cover crop biomass prior to winterkill was 85 lb N/ac. The residual soil nitrate N in the cover crop treatment was only 15 lb N/ac (Table 2) while the residual nitrate N in the no-cover-crop treatment was 114 lb N/ac. The total known N (cover crop N plus residual nitrate N) was 100 lb N/ac for the cover crop treatment. Another cover crop mixture (rye, radish, and camelina) was seeded between the rows of corn on June 22, 2017. On Aug. 16, 2017, the cover crop aboveground portion of plants was sampled in each N treatment. The dry matter weight of the cover crop mixture was 133 lb/ac and was 4% N, resulting in a total uptake of about 5 lb N/ac, which was trivial compared with total corn N uptake. Thus, we wouldn't expect this interseeded cover crop mixture to have much, if any, effect on the corn yield response to N.

The corn N response equations from Figure 3 indicate that N rate required for maximum yield with cover crops was 162 lb N/ac while the N rate required to maximize yield with no cover crop was 161 lb N/ac. In terms of economic optimum N rate (EONR), assuming $3.50 corn price and $0.40/lb N cost, the EONR for no cover crop was 0 lb N/ac while the EONR with the cover crop was 136 lb N/ac. In terms of residual N plus N rate, the economic optimum N (EON, which includes residual nitrate N plus N rate) is 77 lb N/ac for the no-cover-crop treatment and 178 lb N/ac for the cover crop treatment. The cover crop, therefore, had an N drag of about 100 lb N/ac compared with no cover crop (which was similar to the total difference in available N in the soil profile), and the economic loss from the cover crop was about $57/ac due to lost yield at maximum and the cost of additional N. These data clearly demonstrate that cover crop use will benefit water quality (i.e., preventing nitrate from leaching out during the winter and early spring) but can come at a cost to agronomically available N (i.e., more N may be required following certain cover crops) and agronomic productivity. The reduction in yield due to the cover crop could not be explained by soil moisture differences since there were no significant differences in spring soil moisture at planting between treatments.

Conclusions

In all, it is clear that it is not just the C:N ratio that is affecting whether N in the cover crop biomass will be available to the next corn crop, but a host of factors including the total biomass produced, the structure of the plant biomass, and the time of termination. Grass-only cover crop mixtures were not included in these studies as it has been well documented by others that they will not provide N to the next corn crop (e.g., Pantoja et al., 2015). There are many species of cover crops available to plant between early to late August, and each has its own potential benefit. However, if a grower in the upper Midwest is interested in a cover crop that will supply N, the choices appear to be limited only to legumes.

Dig deeper

Gentry, L.E., Snapp, S.S., Prince, R.F., & Gentry, L.F. (2013). Apparent red clover nitrogen credit to corn: Evaluating cover crop introduction. Agron. J.105, 1658–1664.

Pantoja, J.L., Woli, K.P., Sawyer, J.E., & Barker, D.W. (2015). Corn nitrogen fertilization requirement and corn-soybean productivity with a rye cover crop. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J.79, 1482–1495.

Ruark, M.D., Chawner, M.M., Ballweg, M.J., Proost, R.T., Arriaga, F.J., & Stute, J.K. (2018). Does cover crop radish supply nitrogen to corn? Agron J. 110, 1–10.

Stute, J.K., & Posner, J.L. (1995). Legume cover crops as a nitrogen source for corn in an oat-corn rotation. J. Prod. Ag.8, 385–390.

Sapana Pokhrel, Rory O. Maguire, Wade E. Thomason, Ryan Stewart, Michael Flessner, Mark Reiter, Soil health indicators for predicting corn nitrogen requirement in long‐term cover cropping, Agronomy Journal, 10.1002/agj2.21628, 116, 5, (2186-2199), (2024).

S. Cabello-Leiva, M.T. Berti, D.W. Franzen, L. Cihacek, T. Peters, D. Samarappuli, Can nitrogen in fall-planted legume cover crops be credited to maize?, Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 10.2489/jswc.2024.00048, 79, 2, (99-112), (2024).

Debankur Sanyal, Avik Mukherjee, Amin Rahhal, Johnathon Wolthuizen, David Karki, Jason D. Clark, Anthony Bly, Cover crops did not improve soil health but hydroclimatology may guide decisions preventing cash crop yield loss, Frontiers in Soil Science, 10.3389/fsoil.2023.1111821, 3, (2023).

Hunter Bielenberg, Jason D. Clark, Debankur Sanyal, John Wolthuizen, David Karki, Amin Rahal, Anthony Bly, Precipitation and not cover crop composition influenced corn economic optimal N rate and yield, Agronomy Journal, 10.1002/agj2.21265, 115, 1, (426-441), (2023).

Ning Duan, Lidong Li, Xiaolong Liang, Regan McDearis, Aubrey K. Fine, Zhibo Cheng, Jie Zhuang, Mark Radosevich, Sean M. Schaeffer, Composition of soil viral and bacterial communities after long-term tillage, fertilization, and cover cropping management, Applied Soil Ecology, 10.1016/j.apsoil.2022.104510, 177, (104510), (2022).

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.