Managing at a system level—Considering 4R nutrient stewardship and soil health together

While it might not be easy to define soil health, soils with little erosion, higher water stable aggregation, higher organic matter, and incorporated nutrients can function differently than other, less healthy soils. Understanding how the soil functions at a chemical, physical, and biological level is critical to making effective system-level management decisions.

The USDA-NRCS defines soil health as the continued capacity of soil to function as a vital living ecosystem that sustains plants, animals, and humans. While this definition speaks to the importance of managing soils so they are sustainable for future generations, it does not tell agronomists how to see or measure soil health. In 1964, the U.S. Supreme Court considered a case on whether certain pictures or movies could be banned as obscene. Justice Potter Stewart famously wrote that it may not be possible to define what is profane, “but I know it when I see it.” Soil health is like that; as agronomists, we know it when we see it. Soils that are healthy are just different than some of the agricultural soils we encounter. They look, smell, and feel different and function differently than soils that have been degraded. Understanding how the soil functions at a chemical, physical, and biological level is critical to making effective system-level management decisions. Testing soils for chemical and biological indicators can be useful to track changes in the soil over time as practices change. However, the idea of scoring a soil for “good” soil health is being re-evaluated as individual soil health indicators are being tested in relation to crop yield, 4R nutrient management, conservation practices, and nutrient losses.

Soil Health Testing

Farmers, university scientists, and soil laboratory researchers have been trying to describe and measure soil health for a long time. Previous generations may have called it soil tilth or soil quality (Doran et al, 1994), but these terms attempted to communicate how soil physical properties improve its ability to produce a crop. Soil organic matter (OM) is often discussed as a simple indicator of soil health. Many standard soil tests include an analysis for OM that is determined by loss on ignition when a soil sample is placed in a 500°C (932°F) muffle furnace for two hours. This measure is effective at quantifying the total amount of organic-based material in a sample, but it is also a very coarse measure of the material. It includes any material that will burn, yet research is finding that crop yields have stronger relationships to measures of OM quality versus quantity (van Es & Karlen, 2019). The quality of OM in the soil is related to the rate or potential for decomposition of OM and the impact of that decomposition on the labile pools of carbon and nitrogen in the soil.

Soil health cannot be measured by a single set of properties but rather includes physical, chemical, and biological properties. As with conventional soil testing, for soil health assessments, it is recommended that samples be taken at consistent field and weather conditions each time and in the same segment of a crop rotation, the same laboratory is used over time, and progress is tracked over time versus using a snapshot score. The challenges of measuring soil health by soil OM alone has led to an expansion of the types of soil health indicators, and there are a few variations of soil health assessments available through commercial and university laboratories (see box).

With the variety of testing options for soil health, recent research has focused on the interpretation of the results and their relationship to management practices and crop yield. Re-analysis of the 15 soil health indicators measured in the CASH assessment conducted on three long-term sites in North Carolina found that eight of the soil health indicators had a significant relationship to mean yields of corn and soybeans (van Es & Karlen, 2019). Specifically, water-stable aggregation of the soil, OM measured by loss on ignition, citrate-extractable protein, soil respiration of CO2, active carbon, and the mineral concentrations of phosphorus, magnesium, and manganese measured with the Modified Morgan extraction were positively correlated to corn yield, where yield increased when correlated to each measure individually (van Es & Karlen, 2019). Interpreting soil health testing through a single score has been the path for results so far, but further analysis is showing that there are better relationships between yield and individual indictors.

Bavougian et al. (2019) evaluated aspects of the Haney soil health assessment on a long-term research site in Nebraska and concluded that interpretation of the results should shift away from a set threshold to indicate a “good” soil health score and instead measure and track the soil health indicators over time for a specific site. Individual indicators and corn grain yield were impacted by differences in tillage and nitrogen management practices, and the soil health calculation index values were above the previously set good score for all management combinations (Bavougian et al., 2019). Soil OM was shown to be impacted by tillage practices as lower OM concentrations were reported with higher intensities of tillage (Bavougain et al., 2019). When corn grain yield and soil health indicators for the Haney test were measured in the same year, there was no correlation (Bavougian et al., 2019). Both reports found relationships of soil health measures to field management practices, and van ES and Karlen (2019) were able to demonstrate that individual tests versus scores are related to corn grain yields, indicting there is value to testing soil health indicators, but interpreting results based on a score of all measurements may not be the best use of the data.

While there is value to laboratory testing for the quality of OM and the fractions of nitrogen and carbon that can be related to crop yield, other benefits of improving soil health are reduced sediment loss, increased water infiltration, and the potential for reduced nutrient losses from the field. Often these environmental impacts can be observed by watching how a field responds to a 2-inch rainfall. Observations on the amount of sediment suspended in the runoff, volume of runoff from the field, and flow patterns can be insightful to a grower and a consultant. However, just observing water leaving the field with less sediment does not always mean that all environmental goals were met.

Research has shown that the ability of conservation tillage and cover crops to reduce dissolved reactive phosphorus, which drives algal blooms, in runoff varies (Duncan et al., 2019). This can be from increased soil phosphorus concentrations in the soil surface, not incorporating manure or fertilizer phosphorus applications, or the breakdown of organic materials left on the surface of the soil. Implementing 4R practices along with conservation practices, like cover crops and reduced tillage, results in lower phosphorus losses (Qian & Harmel, 2015). Smith et al. (2017) reported that knifing in liquid phosphorus fertilizer compared with surface application in a no-till system reduced both dissolved reactive phosphorus and total phosphorus losses. When considering soil health practices, it is critical to discuss the potential nutrient and management trade-offs and make practice decisions based on the whole system.

Soil Health Assessments

Here are some of the soil health assessments available through commercial and university laboratories:

- Cornell University began offering its Comprehensive Assessment of Soil Health (CASH) in 2006. CASH consists of three levels of soil health analysis, which include laboratory and in-field measurements along with a combined soil health score.

- The Haney test evaluates multiple biological and chemical aspects of a soil sample and is available through a few soil-testing laboratories in the United States. Reports from this test also include a soil health score.

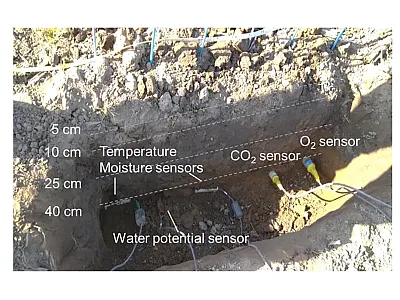

- Solvita has a laboratory-testing option where soil samples are re-wetted and CO2 respiration from the sample is measured over a 24-hour incubation period.

- A phospholipid fatty acid or PFLA test can provide a snapshot estimate of total microbial biomass and give some clues on what categories of microorganisms are active in a fresh soil sample.

- Trace Genomics characterizes soil biology by extracting and sequencing DNA from microorganisms in the soil to characterize what species are active. This information identifies which beneficial or detrimental organisms may be active in the soil.

Conclusions

In general, soils that show high levels of biological activity tend to supply more nutrients to a growing crop, but there is little data and much debate about whether fertilizer rates should be adjusted based on soil health indicators and the relationship of those factors to crop yield. There can be trade-offs between soil health practices like no-till and cover crops with environmental goals like reduced phosphorus loss, making it important to consider all the pros and cons of a management system before changing practices. While it might not be easy to define soil health, soils with little erosion, higher water stable aggregation, higher OM, and incorporated nutrients can function differently than other, less healthy soils.

Dig deeper

Bavougian, C.M., Shapiro, C.A., Stewart, Z.P., & Eskridge, K.M. (2019). Comparing biological and conventional chemical soil tests in long-term tillage, rotation, and N rate field study. Soil Science Society of America Journal83, 419–428.

Doran, J.W., Coleman, D.C., Bezdicek, D.F., & Stewart, B.A. (1994). Defining soil quality for a sustainable environment. SSSA Spec. Publ. 35. Madison, WI: SSSA.

Duncan, E.W., Osmond, D.L., Shober, A.L., Starr, L., Tomlinson, P., Kovar et al. (2019). Phosphorus and soil health management practices. Agricultural & Environmental Letters4, 190017.

Qian, S.S., & Harmel, R.D. (2015). Applying statistical causal analyses to agricultural conservation: a case study examining P loss impacts. Journal of the American Water Resources Association52 (1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/1752-1688.12377.

Van Es, H., & Karlen, D.L. (2019). Reanalysis validates soil health indicator sensitivity and correlation with long-term crop yields. Soil Science Society of America Journal83, 721–732.

Stephen E. Williams, A Review and Analysis of Rangeland and Wildland Soil Health, Sustainability, 10.3390/su16072867, 16, 7, (2867), (2024).

Alex Neumann, Ali Saber, Carlos Alberto Arnillas, Yuko Shimoda, Cindy Yang, Aisha Javed, Sophia Zamaria, Georgina Kaltenecker, Agnes Blukacz-Richards, Yerubandi R. Rao, Natalie Feisthauer, Anna Crolla, George B. Arhonditsis, Implementation of a watershed modelling framework to support adaptive management in the Canadian side of the Lake Erie basin, Ecological Informatics, 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2021.101444, 66, (101444), (2021).

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.