Can winter canola be grown on wide row spacing?

Stand establishment is the most difficult aspect of winter canola production in the Pacific Northwest. A method that has been tried by innovative producers is to plant canola using row spacings much wider than used for winter wheat. This allows wide shovel openers to move dry soil to the areas between the rows and creates a seed row that is shallow to moist soil, allowing the seed to be placed relatively shallow with a minimum of soil cover.

Recent interest in oilseed crushing and biofuels in the Pacific Northwest has heightened interest in canola production. Stand establishment is the most difficult aspect of winter canola (Brassica napus) production in the region. High amounts of crop residues, dry soils, and wide diurnal temperature flux present challenges for stand establishment. If canola stands can be established in the fall, a niche for winter canola exists in the low (<12 inch annual precipitation) and intermediate rainfall (12 to 16 inches of annual precipitation) areas of the Pacific Northwest. Autumn conditions typically are hot and dry during the optimum sowing window for canola, and the seed zone water is often marginal. Equipment and methods commonly used to plant wheat have only been marginally successful with canola. Unlike wheat, canola is a much smaller seed (90,000 to 120,000 seeds/lb) and cannot emerge as well from deep soil placement. It is best to plant canola shallow but into firm, moist soil.

A method that has been tried by innovative producers is to plant canola using row spacings much wider than used for winter wheat. This allows wide shovel openers to move dry soil to the areas between the rows and creates a seed row that is shallow to moist soil, allowing the seed to be placed relatively shallow with a minimum of soil cover. Going to wider rows can allow for better stand establishment but may also have an adverse effect on yield. Recognizing that the effect of row spacing on yield of winter canola in the Pacific Northwest had not been evaluated, we conducted row width experiments in the 2006–2007, 2007–2008, and 2008 and 2009 crop years.

Several studies have been conducted on row spacing of spring canola in more humid areas. These studies have generally focused on row spacing commonly used for planting cereals, but a few have looked at wider spacings. In Sweden, Ohlsson (1974) found that yields were less when canola was grown on 18-inch spacing versus either 5- or 10-inch spacing. In Alberta, Canada, Kondra (1975) reported statistically similar yields for 6-, 9-, and 12-inch row spacing on spring canola but lower yields with 24-inch spacing. A study by Clarke et al. (1978) in southern Saskatchewan, Canada, reported that canola grown at 12-inch row spacing yielded more than broadcast seeding at equivalent sowing rates. In a study in northwest Alberta, seed yield was 36% higher for canola grown at 3-inch row spacing than on 6- and 9-inch row spacing (Christensen and Drabble, 1984). However, this study found no effect between sowing rates of 3 and 6 lb/ac. Morrison et al. (1990) working in Manitoba, Canada showed that canola yield was greater from stands sown on 6-inch spacing compared with 12-inch spacing. In Ontario, Canada, May et al. (1993) found that row spacings of 4 and 8 inches did not influence yield or oil content of three spring canola cultivars but that yield did increase as sowing rate was increased from 1 to 8 lb/ac. Dosdall et al. (1998) found that flea beetle (Phyllotreta crucifera) damage was less when canola was grown at wider row spacings and higher seeding rates. Johnson and Hansen (2003) in North Dakota reported no difference in yield, oil content, date to flower, or lodging on four spring canola cultivars grown on 6- and 12-inch row spacing. In a drought-affected study in New South Wales, Australia, Haskins (2007) found no difference in yield of canola grow on 6- and 24-inch row spacing.

In summary, various studies in several locations over a 30-year period have shown that row spacing sometimes affects yield. Differences in climatic conditions, soil conditions, weed competition, planting date, stand establishment, and seed variables make direct comparison of these studies difficult. In those studies where row spacing was shown to affect yield, the difference in yield was attributed to combinations of weed competition, intraspecies competition of plants along the row, or incomplete exploitation of available water and nutrients by rows being too wide. Winter canola in the Pacific Northwest may be able to tolerate wider rows because of the long growing period. Winter canola is a 10-month crop, which allows time for plants to branch more profusely, thus exploiting the wider rows. Wide rows could be an advantage for herbicide-tolerant canola where any weed competition can be eliminated.

The Experiment

Row-spacing experiments on winter canola were conducted at the Columbia Basin Agricultural Research Center near Pendleton, OR. The soil is Walla Walla silt loam, coarse silty, mixed, mesic, hyperactive Typic Haploxerolls. Soil fertility levels for N, S, and P in the trials were adjusted for a seed yield goal of 2,700 lb/ac (Wysocki et al., 2007b) by shank applying 80 lb/ac nitrogen as anhydrous ammonia and 10 lb/ac S as Thiosol in August. Annual grasses and volunteer wheat were controlled in crop with a postemergence application of 11 oz/ac Assure II in November of the crop year.

The experiment was a randomized complete block design with four replications using row spacings of 6, 12, 24, and 30 inches and seeding rates of 5 and 7 lb seed/ac. Athena winter canola was sown on Sept. 14, 2006 and Sept. 12, 2007. Plot dimensions were 5 by 40 ft. Plots were sown into tilled summer fallow that had been pre-irrigated with 1 inch of water five days before planting. This was done to ensure adequate stand establishment when using a small-plot drill. The seedbed was prepared with one pass of a Brillion rolling harrow. Seed was sown 0.75 inches deep using a Hege plot drill equipped with double disk openers and semi-pneumatic press wheels.

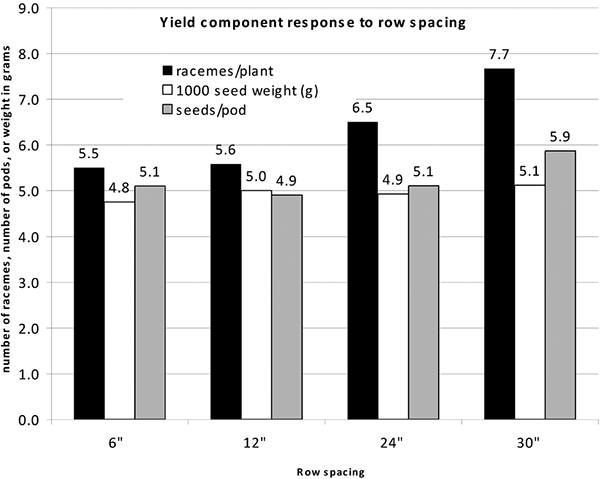

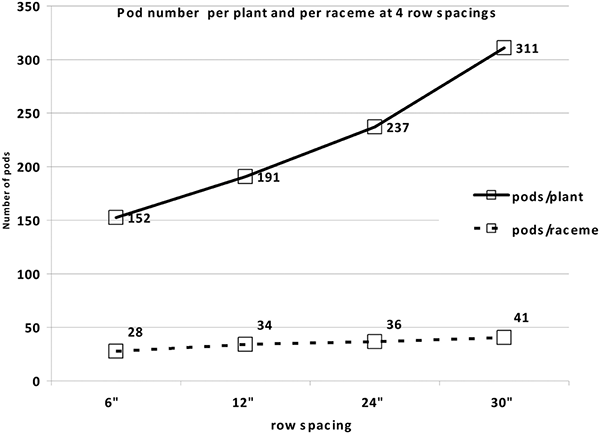

In both years of this study, plots were force-lodged with a John Deere 880 swather equipped with a 5-ft-wide “pusher header” (Wysocki et al. 2007a). Plots were forced-lodged on June 21 in 2007 and on July 7 in 2008. Data on yield components of: (1) branches (racemes) per plant, (2) pods per plant, and (3) seed size (1,000-seed weight) were taken in 2008. Because yield component measurement is very time consuming, it was decided that data be collected on only the treatments that had been sown with 5 lb seed/ac. Three representative plants from these treatments were selected immediately after pushing. Harvested plants were collected, dried, and taken to the laboratory. Racemes and pods per plant were counted manually. Pods were clipped from the plants, gathered, and threshed, and seed yield was determined by weighing. Data were averaged from the selected plants. From these data derived yield components of: (1) seeds per raceme and (2) seeds per pod were computed. Pods per raceme were determined by dividing pods per plant by racemes per plant. Seeds per pod were determined using threshed seed weight from sampled plants, pods per plant, and 1,000-seed weight values. Seed weight was determined from three random 1,000-seed counts taken from harvested seed from each plot.

Stand counts were taken for all treatments at both the 5 and 7 lb/ac sowing rates on two 3.3-ft-long row elements in each plot after harvest. Plant stems in each row element were counted. Plants per linear foot of row and plants per square foot were computed using the average of the two row elements.

Results

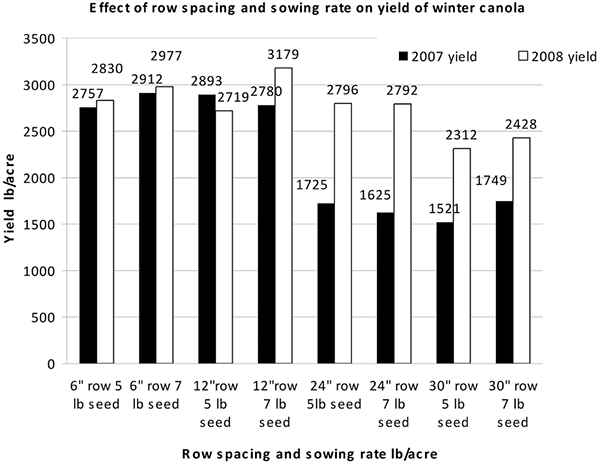

Yields of winter canola at four row spacings and two sowing rates for 2007 and 2008 are presented in Figure 1. In 2007, yields at 6- and 12-inch row spacing were much higher than yield obtained from 24- and 30-inch row spacing. Row spacing of 24- and 30-inch row spacing yielded about 1,000 lb less per acre or only 60% of the narrower spacing. In 2008, 6-, 12-, and 24-inch row spacing yielded nearly the same, and 30-inch row spacing yielded about 300 lb/ac less or about 85 to 90% of the other row spacing.

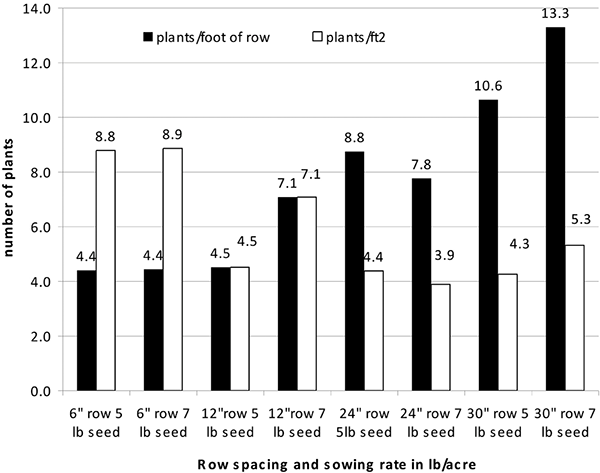

Data on plant stand for 2008 are presented in Figure 2. As might be expected, plant stand along the row and per unit area changed with row spacing and sowing rate. Plants per square foot for 6-inch row spacing at both sowing rates were nearly double that for wider spacing. Plant density at 12-, 24-, and 30-inch row-spacing was in the range of 4 to 5 plant per ft2. The exception was 7.1 plants/ft2 at 7 lb seed/ac on 12-inch row-spacing.

Discussion

Yield results obtained in 2007 and 2008 are somewhat contrasting (Figure 1). In 2007, 24- and 30-inch row spacings yielded 52–60% of the best-yielding treatment that was obtained with 6-inch row spacing and 7 lb seed/ac. In 2008, the highest-yielding treatment was 12-inch row spacing and 7 lb seed/ac, and the wider spacings yielded 73 to 88% of this yield. One possible reason for this difference is that the 2008 growing season was cooler and had more late-season rain. This may have allowed plants in wider rows to compensate better than in 2007. In 2008, yields for both sowing rates at 6-inch spacing were 89 and 94% of the highest yield. Stand counts showed that plant density was nearly 9 plants/ft2 on these treatments. It is possible that these densities were high enough for intraspecies competition to limit yield.

As expected, plant stand along the row (plant/foot of row) increased as row spacing and seed rate increased. However, seeding success actually decreased. If success remained constant with row spacing, then plants/foot of row at 6-inch spacing should increase at 2, 4, and 5 times with 12-, 24-, and 30-inch row spacing, respectively. Based on the measured seed weight of 92,000/lb of Athena seed used in this study, at 5 lb seed/ac, the planting density in seeds/foot of row for 6-, 12-, 24-, and 30-inch row spacing is about 5, 10, 20, and 25 seeds, respectively. Comparing these numbers, seedling success declines from about 80 to 50 to 40 to 35% as row width increases from 6 to 12 to 24 to 30 inches. Regardless, the stands achieved were adequate to yield well.

Yield component data show that canola plants compensated for increased row spacing by branching more and by increasing both the number of pods per plant and pods per raceme. Canola plants did not significantly increase 1,000-seed weight (seed size) or seeds per pod to compensate.

Conclusion

- Growing canola on wide row spacings is feasible. Plantings should be made in late August and early September.

- Planting in wide rows provides an opportunity to reach deeper into the seed bed for moist soil and yet not bury the seed too deeply.

- More branching and producing more pods is primarily how canola responds to the increased space in wider rows. The same response is seen when plant density is low in areas of the stand. Plants produces more branches and more pods. Winter canola has a tremendous ability to compensate by adding branches and pods as space allows.

- Seedling success decreases with wider rows because more plants are crowded along the row.

- Stands of 4 to 5 plants/ft2 are optimum for winter canola.

- Seldom are stands of winter canola uniform across a field. Replanting or overseeding is probably not needed if there is 1 to 2 plants/ft2.

- Winter canola should be planted and emerged by mid-September. This date is earlier for areas in Washington and Idaho.

Dig deeper

Christensen, J.V., & Drabble, J.C. (1984). Effect of row spacing and seeding rate on rapeseed yield in Northwest Alberta. Can. J. Plant Sci.64, 1011–1013.

Clarke, J.M., Clarke, F.R., & Simpson, G.M. (1978). Effects of method and rate of seeding on yield of Brassica napus. Can. J. Plant Sci.58, 549–550.

Haskins, B. (2007). Canola, juncea canola and condiment mustard row spacing trial. Hillston, NSW, Australia: New South Wales Department of Primary Industries. https://bit.ly/38ZTUII

Johnson, B.L., & Hanson, B.K. (2003). Row-spacing interactions on spring canola performance in the northern Great Plains. Agronomy Journal95, 703–708.

Kondra, Z.P. (1975). Effects of row spacing and seeding rate on rapeseed. Can. J. Plant Sci.55, 339–341.

May, W.E., Hume, D.J., & Hale, B.A. (1993). Effects of agronomic practices on free fatty acid levels in the oil of Ontario-grown spring canola. Can. J. Plant Sci.74, 267–274.

Morrison, M.J., McVetty, P.B.E., & Scarth, R. (1990). Effect of row spacing and seed rate in southern Manitoba. Can. J. Plant Sci.70, 127–137.

Ohlsson, I. (1974). Row spacing in spring-sown oilseed crops. In Proc. Int. Rapskongress, 4th, Giessen, West Germany. June 4-8, 1974 (pp. 212–215).

Wysocki, D.J., Sirovatka, N.D., & Thorgerson, P. (2007a). Effect of swathing, “pushing,” or direct cutting on yield and oil content of dryland winter canola and spring rapeseed in Eastern Oregon. In Oregon State University Agricultural Experiment Station, Special Report 1074 (pp. 47–51).

Wysocki, D.J., Corp, M., Horneck, D.A., and Lutcher, L.K. (2007b). Irrigated and dryland canola nutrient management guide. EM 8943-E. https://catalog.extension.oregonstate.edu/em8943

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.