Breeding pulse crops for enhanced plant-based protein

Perspectives, challenges, and recent research efforts

- Pulse crops are a healthy, environmentally friendly alternative source of protein for consumers. With a rising demand for more plant-based food and drinks, more research needs to be done to unlock the true potential of beans, peas, and other pulse crops.

- A review paper and two research studies, recently published in Crop Science, highlight how and why plant breeders are trying to enhance protein content and palatability of pulse products.

It doesn’t matter if you’re strictly vegan or more of a “flexitarian”: if you aim to add more vegetables to your diet, you’re part of an ongoing consumer trend that’s seeking out plant-based meat and dairy alternatives.

Consumers have been steadily switching out their chicken for chickpeas and beef for beans. While animal sources of protein are still dominating the West, the rise of plant-based diets has nevertheless increased demand for more, higher quality, plant-based sources of protein in the market. There are good number of reasons for this, too. Plant-based proteins are cited to be low in saturated fats and high in fiber with cropping systems that are more environmentally sustainable than traditional animal protein production.

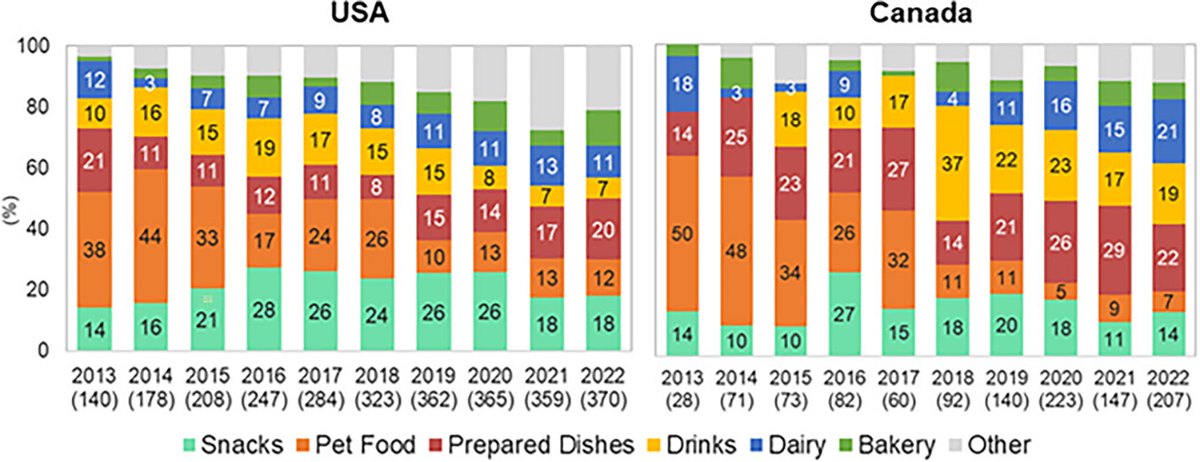

This demand has opened the door for an often-overlooked food group to step into the spotlight: Pulse crops—the dry, edible seed of legume plants, like beans, peas, and chickpeas—have gained attention as a viable source of protein. Recent market insight from Towards Food and Beverages predicts the legume market to expand from $15 billion to $24 billion in 2034, largely due to increased consumer interest in plant-based meals.

The ideal party food

Beans, lentils, and other pulse crops are more than just a dietary fad. In many countries, they’re staples—the star of a Sunday night dinner. Valerio Hoyos-Villegas, assistant professor of plant breeding and genetics at Michigan State University, ultimately centered his career around pulses because of his childhood family meals.

“What drew me to bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) breeding,” explains Hoyos-Villegas, “Was the fact that [beans] were my primary source of protein growing up in Colombia. … Food also serves as a bonding mechanism, and in Colombia, when there are family meals or social events—they frequently involve beans. So, beans have always felt personal to me.”

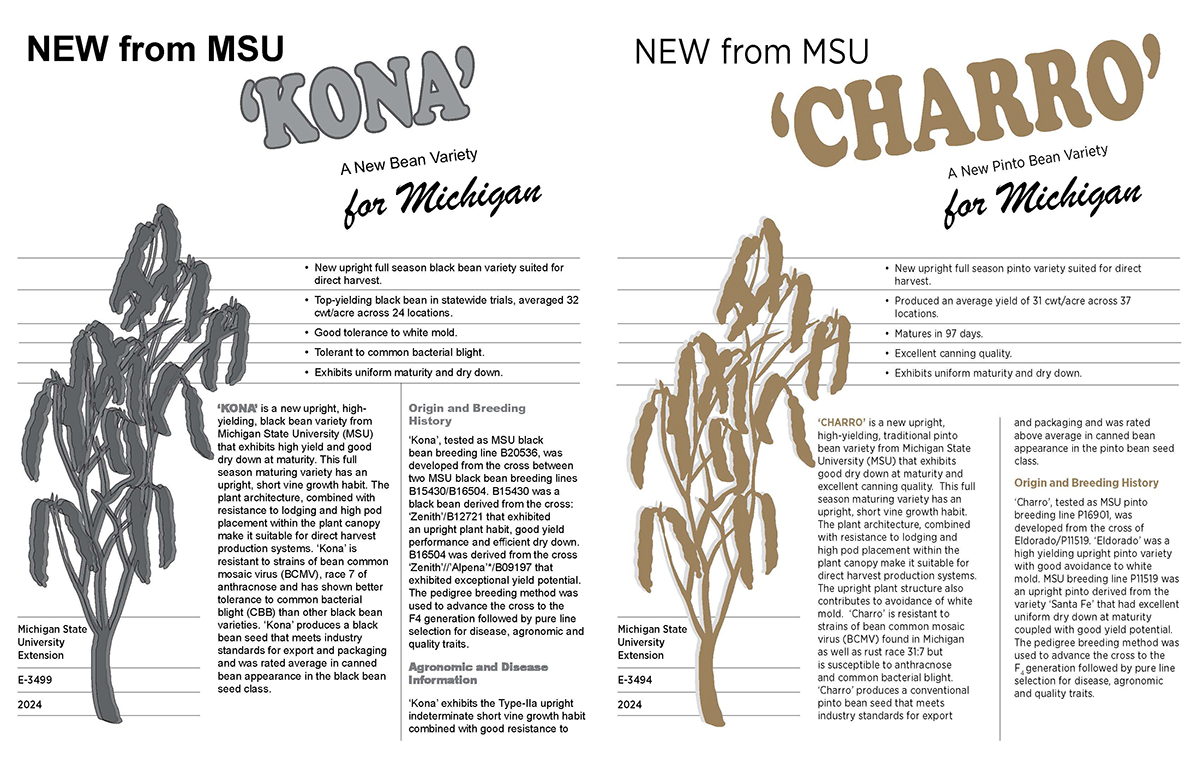

Hoyos-Villegas runs a dry bean breeding program at Michigan State. “I did my Ph.D. at Michigan State, in the lab that I lead now. It’s a great honor,” adds Hoyos-Villegas. “I had a unique opportunity to lead a breeding program that is over 100 years old now.”

As a crop breeder, Hoyos-Villegas’ job is to produce new bean varieties that are superior to older lines. They are meant to be healthier, resistant to diseases, and sustainable. In a new Crop Science review that Hoyos-Villegas coauthors, he advocates for the importance of agriculture in this field—it produces all the raw materials for these plant-based products, after all.

Adding amino acids, eliminating antinutrients

Beans, like many pulses, are already valued by consumers for their nutritional value—they provide energy, fiber, micronutrients, vitamins, and protein. So, what’s there to improve?

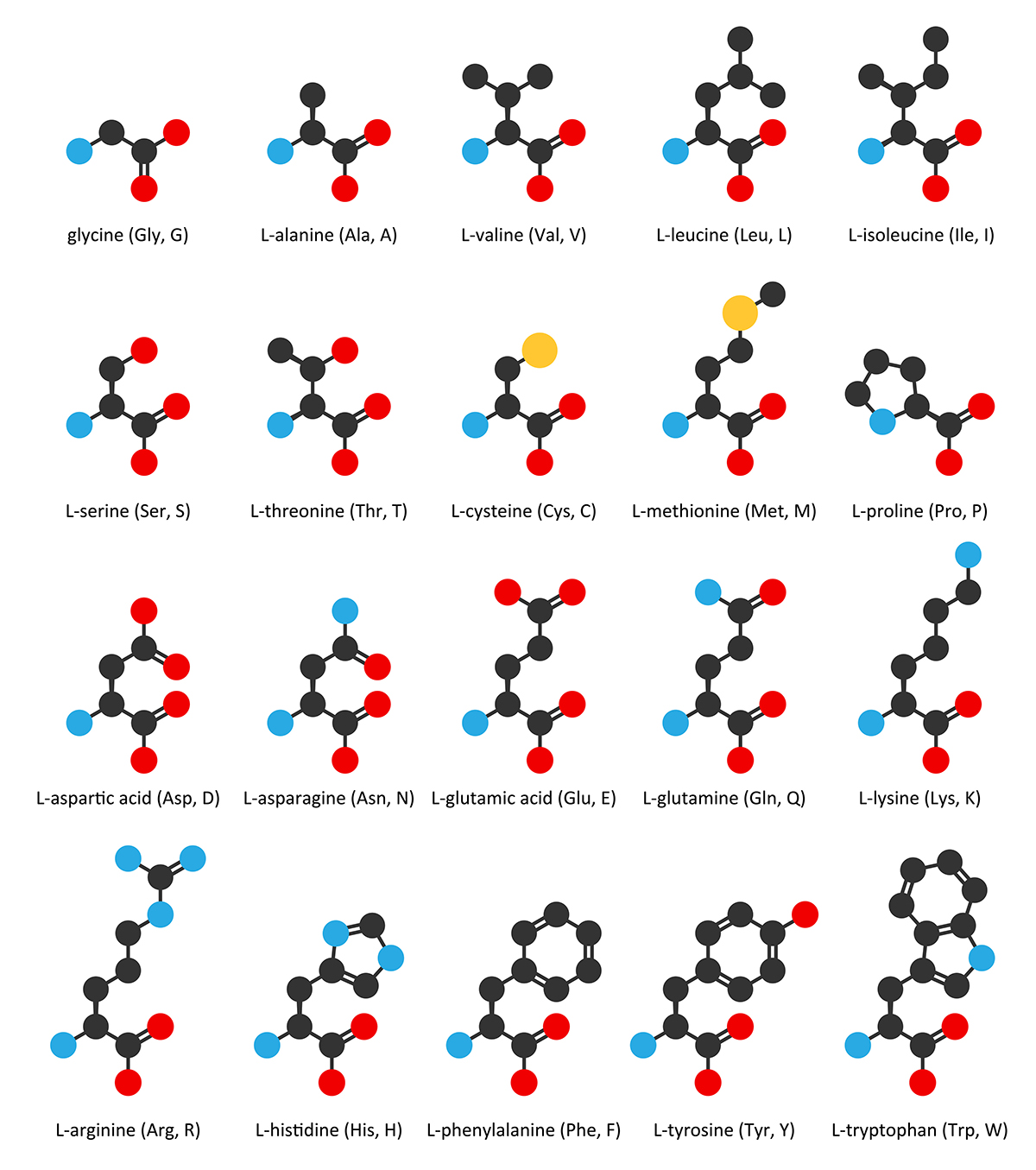

Hoyos-Villegas explains that beans, while rich in other compounds, are lacking in two special, sulfur-containing amino acids: methionine and cysteine.

“If we could increase that profile, we would have a pulse species with a full array of amino acids,” he says.

But what is so special about these two, tiny molecules? Reduction in sulfur amino acids actually reduces protein digestibility, reducing the crop’s nutritional value. Not having sufficient amounts of amino acids (especially methionine, which the human body cannot produce on its own) also makes this pulse crop an incomplete protein.

There are other challenges bean and pulse crop breeders face. Many pulse crops contain “anti-nutrients,” compounds that can have negative effects if eaten raw and in sufficient quantities. Think about how raw, dry beans need to be correctly prepared in order to eat safely.

“So, beans do have to be cooked,” explains Hoyos-Villegas. “They cannot be eaten raw. They have heat-labile proteins (e.g., lectins) that we cannot digest readily. And so those are what we call anti-nutritional factors. When cooked they are denatured, and that's what makes them safe to eat. … But if we could reduce most of this anti-nutrient activity, then the potential of beans really changes. Using beans and pulses in industrial processes as whole seeds or ingredients in plant-based products will require innovations from crop breeders and industry processors in order to minimize the presence of anti-nutrients.”

Improving amount and quality of protein in pulses, in addition to increasing micronutrient content, decreasing anti-nutrients, and increasing yield, are all ways to increase the value of pulse crops and combat malnutrition in areas where pulses are the predominate source of protein.

Using RNA-seq to identify genes related to pea protein

Just how do breeders attempt to tackle these goals? There are many methods agriculturalists can use to increase protein content in their crops. Researchers at the University of Saskatchewan recently published a Crop Science study about how they’re doing this in pea (Pisum sativum) plants by analyzing RNA sequences (RNA-Seq) with supercomputers.

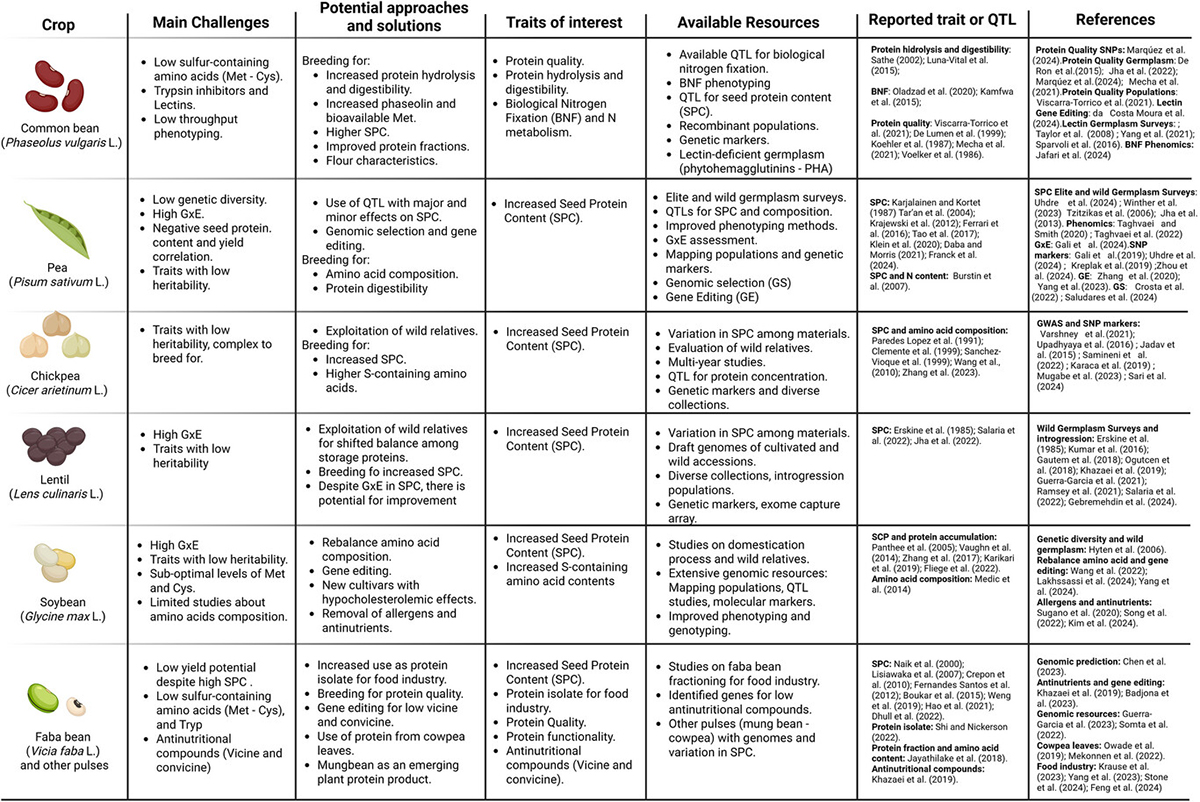

Unique challenges for different legumes and pulse crops

While all breeders of pulse crops and legumes are trying to increase digestible seed protein, not all crops are made the same. Breeders who specialize in chickpeas will encounter different challenges compared with pea breeders. Hoyos-Villegas summarizes key challenges for different plant-based sources of protein as thus:

- Beans: Reducing compounds that reduce protein digestion (trypsin inhibitors, lectins).

- Peas: Decoupling the negative correlation between yield and protein. Typically, due to the way pea plants metabolize nitrogen, increasing yield decreases protein concentration.

- Lentils: Understanding how genes of interest interact with the environment, making lentil crops more reliable.

- Soybeans (which are not pulse crops, but they are legumes): Decoupling the correlation between amino acid and oil production.

- Minor pulses (faba beans, mung beans, etc.): Increasing research and knowledge about minor the minor pulses—as a whole, these plants are unfortunately understudied.

And other, legume-specific issues, are detailed in the table above.

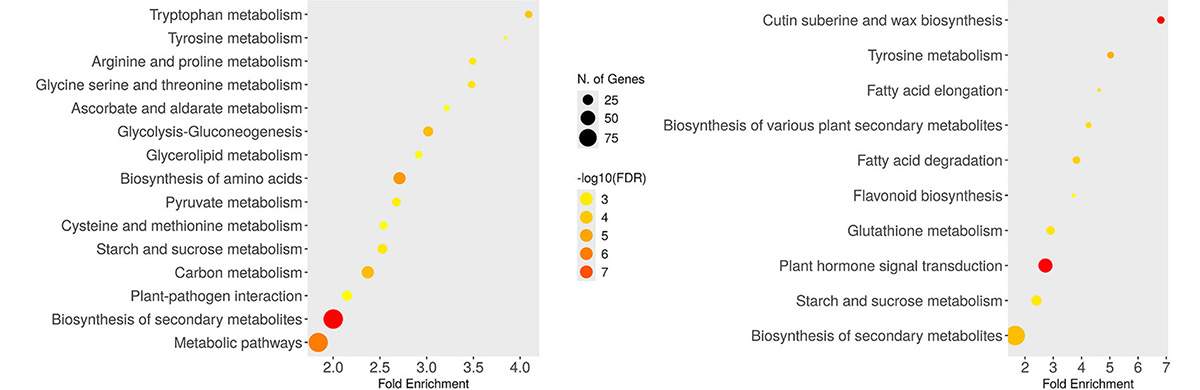

Junsheng Zhou, postdoctoral fellow and lead author of the study wanted to identify genes that are potentially associated with total seed protein and sulfur amino acid concentration. By comparing three lines of pea—one with high total seed protein, one with high amounts of sulfur amino acids, and one with low amounts of both—he could analyze which lines express which genes.

Zhou harvested developing pea pods, extracted RNA sequences from them, and compared the sequences to determine which lines increased (upregulated) or decreased (downregulated) certain genes at different time points during plant growth.

“We compared the gene list of the high-protein line to the gene list of the low-protein line. What’s overlapping?” asks Zhou. “There might be some genes that are fundamental for the overall developmental process. And those that are uniquely expressed in high-protein lines—those might be the genes that associate with high protein.”

To confirm that these genes are associated with protein development, the authors compared these genes with a public database to determine each gene’s function.

“We used this list of uniquely expressed genes to do gene ontology and enrichment analyses where we got to know what the genes are involved in structurally (for the development of the protein) and which pathways these genes are involved in.”

Zhou’s study is a continuation of his previous work. He previously used quantitative trait loci (QTL) analysis to look for broad chromosome regions associated with protein concentration in his pea lines. This study builds off of those findings, using a method that locates specific genes controlling protein content.

“[RNA sequencing] provides higher resolutions,” Zhou explains. “But I think the QTL mapping and RNA sequencings can be partnered together to increase [accuracy].”

Zhou’s findings required a lot of processing in order to narrow down the specific candidate genes. “From our starting point, we found more than 20,000 differentially expressed genes, but we used different methods to filter and narrow them down to around 500 genes that potentially are related to protein or sulfur amino acid concentrations. From those 500 genes, we might have the potential to develop gene-based markers that will help breeders know which [new] lines will have higher amounts of protein.”

Zhou hopes to next measure metabolites (small molecules made during metabolism) in his lines in order to better “understand the biological mechanisms” behind high-protein plants, establishing the indirect links he has found so far between the genes and traits as more concrete relationships.

No rest for the crop breeder

Clearly, developing new pulse crop lines is a process that takes years, despite any tools that can speed up a plant breeder’s program.

“Protein is genetically complex,” Hoyos-Villegas says. “Instead of being controlled by a few genes of large effect, it's controlled by hundreds and thousands of genes of very small effects that interact together in different ways. And so that makes breeding for protein … really slow.”

But Dhyan Palanichamy, plant breeder and data scientist at Ingredion, says that consumers rapidly change their minds on what they want to buy. “The market doesn't wait for a breeder to release his or her variety.”

So, how do pulse crop breeders cope with such volatile consumer markets, when plant breeding takes so long?

“All the successful breeders that I've talked to have multiple projects going on. And they ‘saw the future’ a long time ago,” says Palanichamy, coauthor of the recent Crop Science review. For example, if his colleagues were to develop a fava bean protein powder for the market, that sort of product would have been in development for at least 20 years prior to sales—even if the timing seems “perfect” from an outside perspective. That’s why it’s crucial to juggle multiple different projects at the same time.

This product development involves several different teams working on several different avenues. “Those 20 years include foundational research (collecting plant genetic material and breeding), extension work (commercial seed production, building grower networks, and refining agronomic practices), and commercialization hurdles (finding markets, securing farm insurance, and getting inputs approved),” Palanichamy explains. “The market window is incredibly narrow and unpredictable, which is exactly why it’s so important to have several different projects running in parallel—one of them will be ready when the opportunity finally opens.”

To demonstrate how quickly the market shifts, Palanichamy explains that when he started collaborating with Hoyos-Villegas on their paper, there was a high demand for meat substitutes. Since then, the market has shifted to producing more cold-pressed plant-based products, such as shakes, cereals, and protein bars.

He adds that consumers will likely shift back to wanting meat substitutes—the market perpetually shifts back and forth.

“It's cyclical,” Palanichamy says. “And when [the market eventually] comes back [to meat substitutes], we better be ready with great varieties that are sustainable, have the best flavor, and don't require much processing. … When the second wave happens, it'll be huge I think.”

In the meantime, the industry has gotten creative with its plant-based products, too: Pea and other pulse crop by-products can be used as material in plant-based protein bars, shakes, and egg replacements, which reduces food waste and valorizes by-products.

Putting plant-based products to the (taste) test

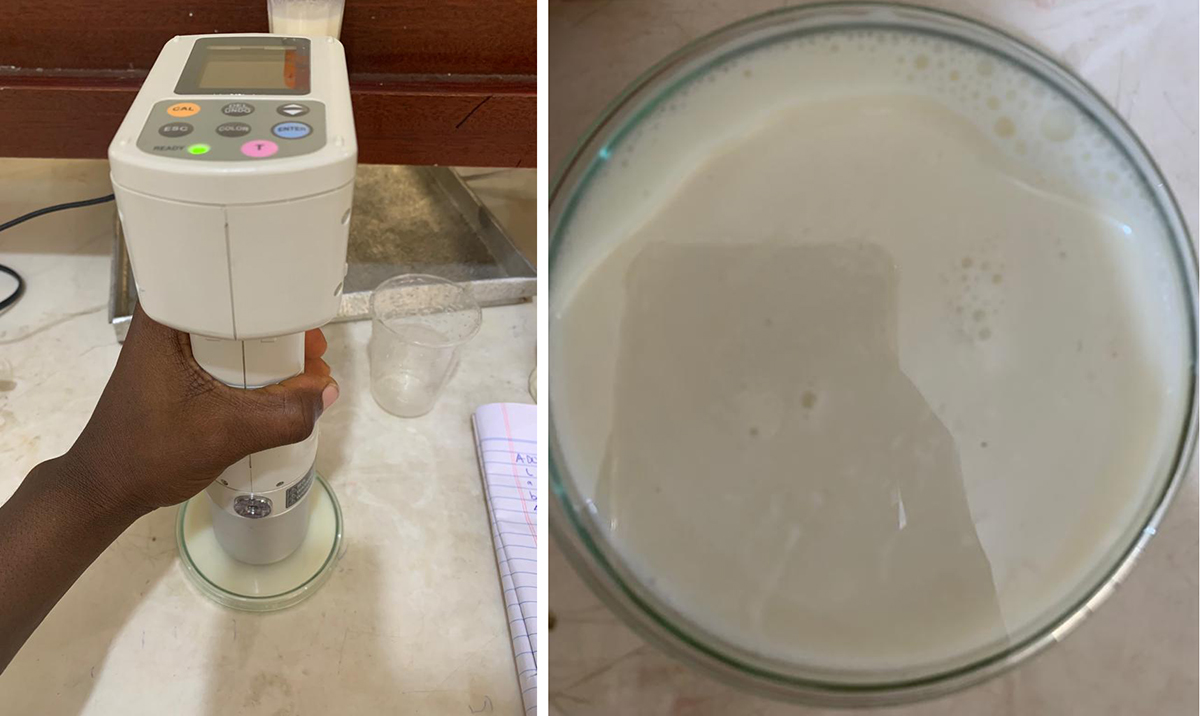

But for any of these new, plant-based products to be successful, consumers have to like and purchase them. Another Crop Science study explored this by evaluating consumer perception of yogurt made with common bean.

Eric Owusu Mensah, food scientist at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Ghana, explains that exploring a “locally available, affordable, and nutrient-rich” ingredient as a dairy alternative is “an opportunity to heighten food security, product diversification, and reduce over-reliance on dairy products.”

His research team compared physiochemical and sensory properties of yogurt made with one of two varieties of common bean. The yogurts were made with either 45, 55, or 75% milled bean and compared with a yogurt made completely from milk powder. They analyzed properties such as pH, texture, and color in addition to conducting a sensory panel with 50 untrained panelists to determine acceptability of the yogurts. The researchers found that yogurt made with 55% Adoye bean was the second-most liked yogurt product after the control, as it was thicker and had a more suitable flavor compared with other bean-based yogurts.

Unfortunately, one of the product’s greatest challenges is what makes it so novel: The researchers needed to combat an excessive “beany” flavor while making the yogurt. Mensah clarifies that despite the potentially off-putting flavor, common bean is a valuable source of protein that is worth the challenge.

“Although the ‘beany’ flavor is a known challenge, common beans are nutritionally powerful—rich in protein, fiber, minerals, and antioxidants,” he says. “Working with a challenging yet abundant resource allows opportunities for innovation in processing techniques (soaking, blanching, germination, fermentation, enzymatic treatment, etc.) to reduce the off flavor[MN1] , making the product more acceptable.” One of those pretreatment methods—soaking the beans for 12 hours in 0.5% Na2CO3—was successful in reducing some of the off flavoring.

They concluded that a yogurt product made with 55% common bean has potential in this industry. Mensah says he would like to further explore “flavor-masking techniques, optimized fermentation conditions, and additional stabilizers to improve texture” in addition to testing a wider demographic and developing flavored yogurts.

“I think it's all about taste,” adds Palanichamy, further emphasizing that the success of plant-based protein depends on consumer perception. “And you know, if we can make plants taste really good, it will be good for everyone.”

Dig deeper

Cordoba, H. A., Sadohara, R., Gali, K. K., Zhou, J., Hart, J., Alexandre, A. C. S., Cichy, K., … & Hoyos-Villegas, V. (2025). Breeding for plant-based proteins in pulse and legume crops: perspectives, challenges and opportunities. Crop Science, 65, e70137. https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.70137

Zhou, J., Gali, K. K., Reddy, L. V. B., Chakravartty, N., Tar'an, B., & Warkentin, T. D. (2025). RNA-Seq-based gene expression analysis of seed protein and sulfur amino acid accumulation in developing pea seeds. Crop Science, 65, e70159. https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.70159

Mensah, E. O., Agbodeka, C. Y., Okyere, F., Amoa-Owusu, A., Osei-Wusu, F., & Frimpomaa, C. (2025). Potential utilization of two new varieties of Phaseolus vulgaris in yoghurt manufacturing. Crop Science, 65, e70129. https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.70129

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.