Getting rice to chill in the wake of a warming planet

Two new studies approach temperature sensitivity in rice varieties to explore different ways to improve its resilience

As climate change reshapes growing conditions worldwide, researchers are racing to reimagine how staple crops like rice can adapt. Higher temperatures can increase evaporation and dry out the soil, and variable temperature conditions can also retard seed germination, increase injury and rot, delay vegetative growth, and produce poor grain filling. As temperature and precipitation patterns shift, growers may explore new territories that may leave rice, in particular, vulnerable to cold sensitivity. This article explores how advances in rice genetics are helping scientists develop more resilient crops capable of thriving in increasingly unpredictable conditions.

Agriculture is facing a pivotal moment as two crises converge—the need to feed an ever-growing population and climate change.

The pressure to find new, innovative ways to feed an expanding population is not new. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations predicts food production will need to increase by 70% to meet the needs of the global population by 2050. Agronomists have worked with geneticists to develop new cultivars to increase productivity, tamp down pests, and use resources more efficiently. These successes have bolstered modern agriculture, but it may not be enough to keep pace as society expands.

Climate change complicates efforts to increase production. As the planet warms, long-established temperature and precipitation patterns will change, shifting growing seasons and increasing the incidence of extreme weather conditions. Growers will also need to contend with new and emerging pests, soil degradation, and a reduction in arable land. A more comprehensive and holistic strategy is needed to address complications caused by climate change while also increasing agricultural production.

Rice: a staple crop to feed the world

People have been domesticating crops for thousands of years by selecting for traits that are beneficial to the core objective—producing more food. These advances have led to larger seeds, increased yield, and reduced thorns and seed shedding. These traditional methods are effective, but slow, and often follow a circuitous route to the required outcome.

To address emerging and complex research questions, researchers often focus on one crop to represent the broader field of agriculture. Rice, a staple crop that feeds more than half the world’s population, has evolved significantly in the thousands of years that it has been under cultivation.

In recent years, researchers have employed genetics to put traditional domestication efforts into overdrive. Directly tweaking a gene provides a more straightforward path to increased production. In the 1960s, researchers at the International Rice Research Institute sparked the Green Revolution by crossing a Taiwanese rice variety that contained the SD1 gene with a Peta variety. The cross produced IR8, a high-yielding, semi-dwarf rice variety.

Despite the promise of the Green Revolution, temperature remains a hindering factor in rice production. Rice is typically grown in tropical and subtropical regions, where temperature regulates growth behavior and grain yield. While a warmer planet may seem ideal for rice, higher temperatures can increase evaporation and dry out the soil. Variable temperature conditions can also retard seed germination, increase injury and rot, delay vegetative growth, and produce poor grain filling. As temperature and precipitation patterns shift, growers may also explore new territories that may leave rice, in particular, vulnerable to cold sensitivity.

“Rice is highly sensitive to cold stress, especially during the seedling stage, which is critical for establishing healthy crops,” explains Khushboo Rastogi, a recent Ph.D. graduate from Endang Septiningsih’s lab at Texas A&M University. “Even brief exposure to temperatures below 15 °C (60 °F) can impair early growth, reduce tiller number, and ultimately lower yields.”

Breeding rice for cold tolerance has the potential to open new regions for rice cultivation. This motivation has been central to rice-improvement programs. Unlike some other traits, cold tolerance is influenced by multiple genes or quantitative trait loci (QTL). The culmination of two decades of research has detailed the complexity of the genetics underlying cold tolerance and plant development.

For example, several QTL regions, including qCTS12, qLTG3-1, and qCtb-1, have been linked to chilling sensitivity. Each QTL is located on a different chromosome and may affect different pathways that affect growth and productivity. The factors associated with cold tolerance are varied, including plant height, chlorophyll content, and water stress, but the interplay between these different characteristics at the genetic level remains elusive.

This article examines two lines of research exploring the question of cold sensitivity and production through the lens of rice genetics.

Pinpointing the genetics to withstand cold and enhance recovery

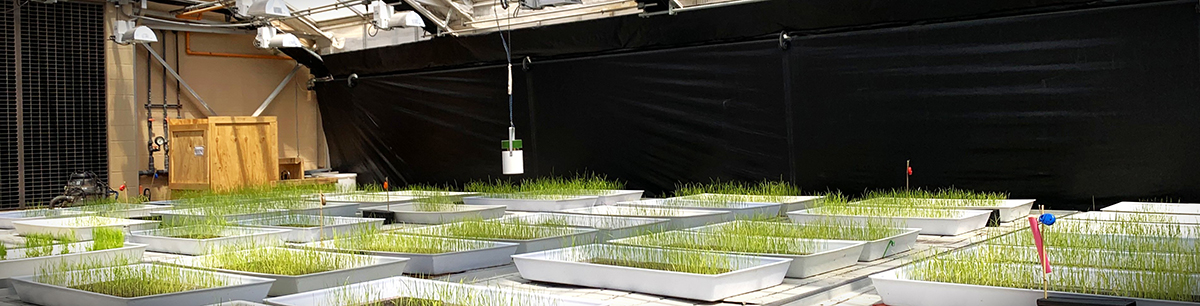

A team of researchers at Texas A&M University performed a genome-wide association study (GWAS) to identify robust and stable QTLs and genes associated with cold tolerance in rice seedlings across diverse environments. Their efforts aimed to clarify the genetic basis of cold tolerance in this crop with the goal of developing new varieties that would improve yield under variable environmental conditions. Their work is detailed in a paper published in the journal Crop Science.

“Our motivation stemmed from the need to understand and harness the natural genetic diversity for cold tolerance present in global rice germplasm, especially given the increasing adoption of direct seeding practices and shifting climate patterns,” says Endang Septiningsih, professor in the Department of Soil and Crop Sciences at Texas A&M University and senior author on the study. “By applying genome-wide association analysis across a diverse panel of 238 accessions, we aimed to identify genetic loci and accessions that could serve as valuable breeding resources for developing cold-resilient rice varieties.”

The rice accessions in the GWAS analysis were obtained from Asia (165), North America (48), Europe (16), South America (5), and Africa (4). The analysis identified 77 QTLs for cold tolerance and recovery, of which 31 were new to the research community.

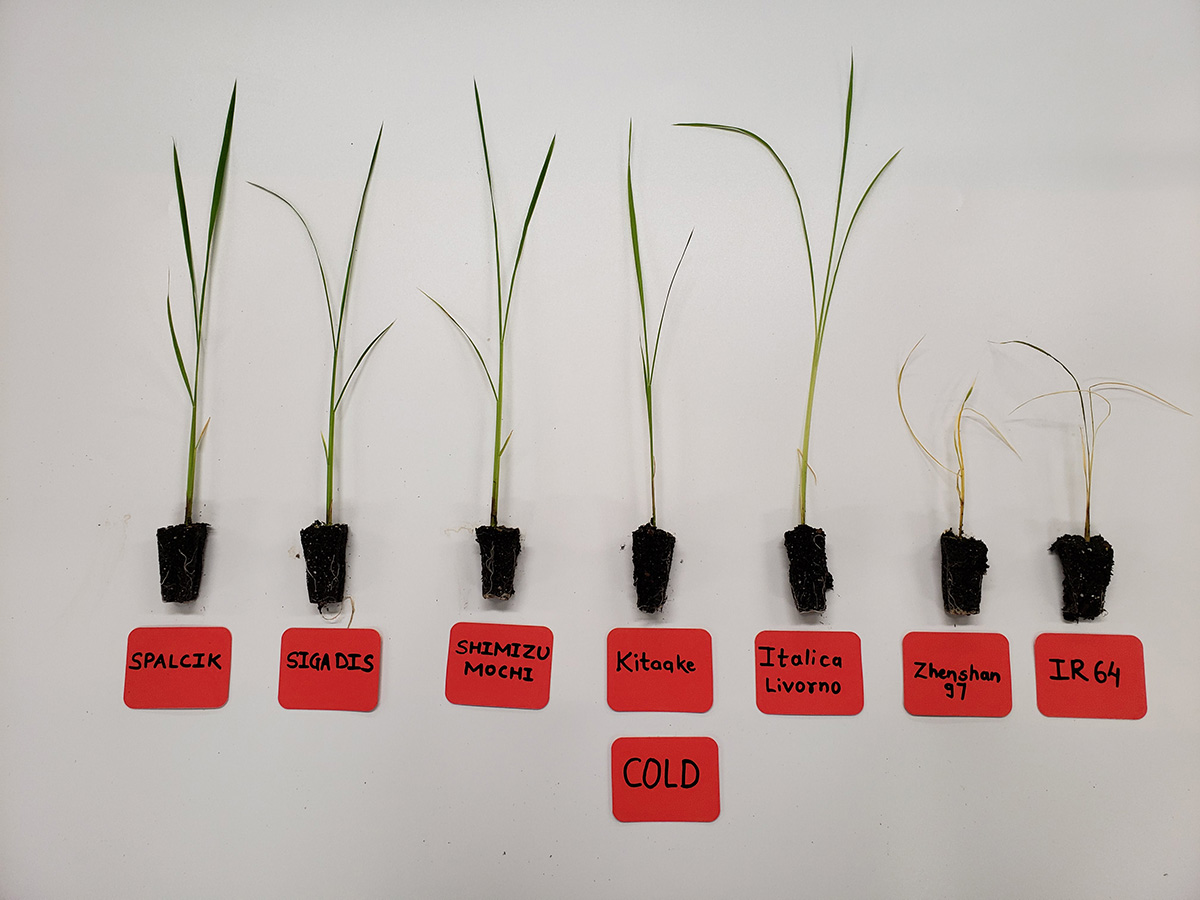

“Not all rice responds equally to cold,” says Sumeet P. Mankar, a Ph.D. graduate from Septiningsih’s lab and a contributing author on the study. “Some varieties, especially temperate japonica lines, showed greater resilience under cold stress and better recovery, indicating that choosing the right variety can make a real difference.”

The analyses suggest three rice varieties from the temperate japonica group have the greatest potential for cold tolerance at the seedling stage, including Sigadis (originating in Indonesia), Spalcik (originating in the Russian Federation), and Shimizu Mochi (originating in Japan). These varieties demonstrate exceptional cold tolerance and post-stress recovery across multiple measured traits, including survival rate, cold tolerance score, plant height, chlorophyll content, biomass, and new leaf emergence.

“We found that the ability of a plant to recover after a cold spell is just as important as surviving the cold itself,” says Rastogi, first author on the study. “Breeding for recovery traits can help ensure more stable yields, despite early-season chilling events.”

The QTLs identified in this study offer new targets that the research community can explore to produce cultivars with enhanced cold tolerance across different growth stages. Additional work could also examine the molecular markers that would elevate desirable traits with greater efficiency. This information could be crucial in developing climate-smart rice varieties that have greater resilience that would allow this integral crop to thrive in areas susceptible to cold snaps without adversely affecting crop yield.

Dwarf crops could play an oversized role on a warmer planet

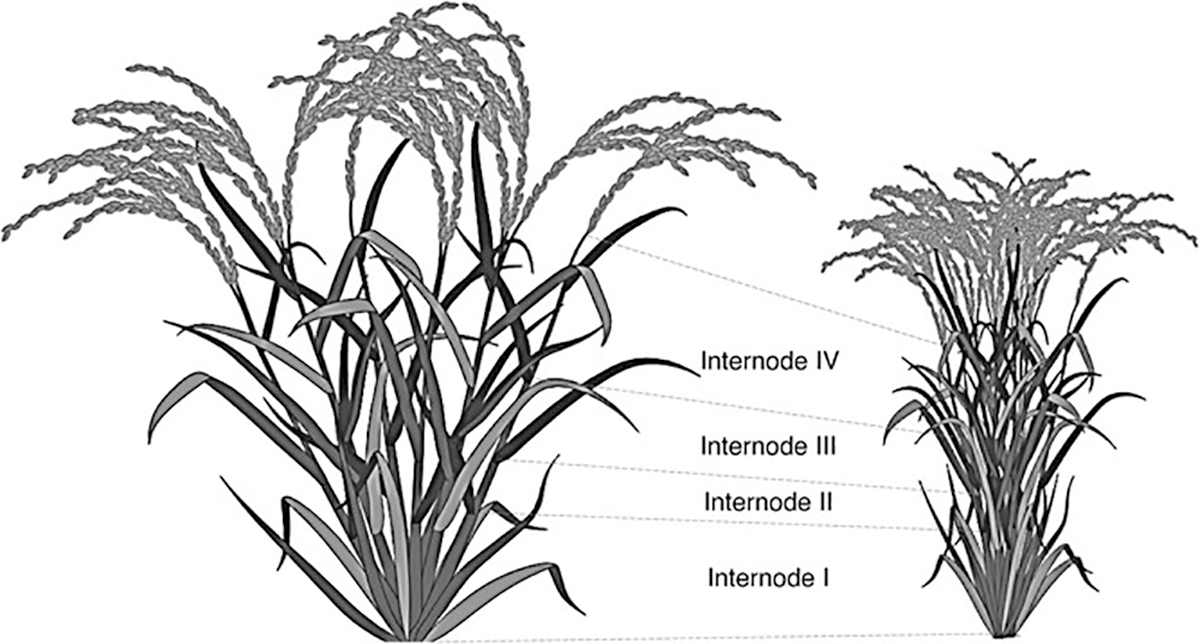

In nature, plants adapt to colder conditions by reducing their size to take advantage of the warm pockets of air near the ground. Dwarfism also helps plants withstand drought, extreme temperature, and limited resources. All of these factors are likely to occur as the planet warms. Dwarf crops also require less labor to maintain the fields, reducing the input of water, nutrients, and fertilizers on the land. These plants are also partial to high-density planting, a beneficial option for regions with limited space. While dwarf plants offer many benefits, there are agricultural trade-offs.

Dwarfism can reduce fruit size and overall productivity. In addition, plants aligned in a high-density planting can trigger shade avoidance syndrome, a condition activated by changes in light levels. Plants that experience shade avoidance syndrome alter their growing patterns to outcompete their neighbors by triggering pathways to grow taller. Dwarf plants can reduce this stress but not eliminate it.

Plant size is regulated by hormones, including auxins, gibberellins, ethylene, brassinosteroids, and cytokinins. These hormones act like a switch turning genes on and off to regulate shoot and root growth. With this knowledge, researchers have used gene-editing tools, such as CRISPR/Cas9, to leverage different hormones to maximize dwarf varieties that improve resistance and yield stability.

Strategically, the diminutive cultivars provide another avenue to address the dual crises of climate change and productivity. Its success requires identifying and leveraging dwarfing alleles and the hormones needed to activate the necessary pathways to achieve the desired results. Unfortunately, most studies that explore these options underreport key characteristics, such as productivity, harvest index, and stress tolerance, in the miniature plants.

Maximizing dwarf cultivars to increase production

A team of researchers at Wonkwang University in South Korea examined the current scientific literature to identify research gaps where future studies could be focused on for developing new approaches to address productivity in dwarf plants. Their work is detailed in an article published in the Agronomy Journal.

“There are abundant candidate genes for making dwarfs without yield penalty,” says Sujeevan Rajendran, Ph.D. candidate at Wonkwang University and lead author on the study. “Researchers limit their study to gene characterization and either do not consider productivity testing or underreport non-productive dwarf-related genes where these data are hidden forever for breeders and farmers.”

Past research points to three plant hormones—gibberellin, brassinosteroid, and auxins—that play an integral role in stem elongation and internode architecture. These hormones also interact with plant proteins (DELLA) and transcription factors (PIF and BZR1), which are central to the shade avoidance response. The review also points to gibberellin- and brassinosteroid-related genes, including D18, EUI1, D1, D11, and D61 that affect cell elongation and growth.

Future studies could focus on these targets to enhance dwarf cultivars to not only control shade avoidance syndrome, but also increase productivity. The authors support evaluating the most promising cultivars during multi-environmental trials to quantify agronomic traits for breeding programs. These additional studies would help researchers and growers understand how the modified genes can be used to fine-tune height without impeding yield. This research approach would help the agriculture community understand how the plants perform under different environmental stressors and agricultural practices.

“As researchers, our goal is to prepare our crops and farmers to future climate-related problems [and] build an arsenal of novel cultivars [that] can be planted in limited space and limited resources, especially in smart farms,” says Chulmin Kim, professor in Plant Molecular Breeding Lab at Wonkwang University and senior author on the study. “These cultivars can also be further modified to produce food in [agricultural] systems.”

The future of rice production involves creativity and innovation

The field of genetics offers a shortcut to traditional breeding programs. By targeting specific locations in the genetic code, researchers can develop cultivars that can withstand and outperform in the face of different environmental stressors. Rice provides a lens to examine the genetic complexity that controls temperature sensitivity. It also lays out a template to examine how to manipulate hormonal switches to address growth and productivity in dwarf cultivars. These two active avenues of research open key insights that can enhance rice, but also illuminate how to modify other crops to ensure plants can thrive in new, underutilized environments, ultimately contributing to a food-secure future.

“Climate resilience should not compromise yield or quality,” says Septiningsih. “[It] will take a determined effort . . . to transfer valuable alleles into elite breeding lines for the next generation of stress-tolerant cultivars, [but] this will ultimately translate to better crop establishment, more consistent performance in unpredictable seasons, and long-term productivity.”

Dig deeper

Check out the original research cited in this article:

Rastogi, K., Mankar, S. P., & Septiningsih, E. M. (2025). Genome-wide association study for traits related to cold tolerance and recovery during seedling stage in rice. Crop Science, 65, e70003. https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.70003

Rajendran, S., Chun, S. M., Kang, Y. M., Hwang, G. H., Lee, D. H., Lee, S.-H., Lee, B., Kim, H. C., Bae, J. H., & Kim, C. M. (2025). Small and strong: Dwarf cultivars as a strategic response to shade avoidance syndrome through molecular, hormonal, and breeding innovations. Agronomy Journal, 117, e70122. https://doi.org/10.1002/agj2.70122

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.