Statistics show value in old-school crop condition reports

Every week through the growing season, the USDA issues reports on the conditions of crops across the country. Speculators and agrobusinesses use this information to help make important decisions.

Scientists haven’t put much stock in the data because they’re based on subjective assessments. However, a pair of meteorologists took a closer look at decades of corn condition reports in the U.S. Midwest, using statistics to evaluate their relationship to actual crop yields and climate over time.

Their findings, published in Agronomy Journal, show some strong correlations confirming the value of those qualitative data and provide insights into how relationships among perceived crop conditions, yields, and climate have been shifting over time in the Midwest.

These days, there are lots of fancy ways to assess how crops are faring: complex models, remote sensing, and deep learning, for example, all requiring complex tools like satellites, drones, and computers. It’s enough to make us humans feel a little insecure about our own powers of observation.

Turns out, those powers stack up pretty good.

According to a recent study in Agronomy Journal, the humans behind the weekly Crop Progress and Conditions reports issued by the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) do a good job of predicting corn yield in the Midwest without the lag time or high-tech hardware required by other methods. By mining these decades of data, which have been largely ignored by academics as subjective, the two meteorologists behind the study validated the reports’ predictive worth while also uncovering correlations with climate change.

“I wanted to do this because these are qualitative data that are relatively easy to calculate,” explains first author Logan Bundy, who recently completed a master’s in meteorology at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and is pursuing his doctorate at Northern Illinois University. “The fact that they do a good job means that everybody can use the data and calculate these things on their own, if they wanted to. It’s just an easy, initial-look approach.”

Every Monday from April to November, an army of extension agents and Farm Service Agency staffers across the country file a simple report assessing crop conditions in their counties. Based on first-hand knowledge and what they hear from farmers, they evaluate the crops—NASS tracks 11 major ones—on a five-point scale from very poor to excellent. By the end of the day, these reports have been aggregated, processed, and made available to anyone who wants them. Typically, scientists pay little attention.

A lot of other folks, however, pay very close attention. In fact, these reports are among NASS’s most requested publications, used by speculators in agricultural commodity futures and business strategists, among others. This includes people like Jon Davis, chief meteorologist of data analytics company Everstream Analytics, whose job it is to guide big corporations through the murky waters of climate change.

Simple Data Inform High-Stakes Choices

For clients that include AB InBev, Campbell, and Unilever, Everstream eyes the horizon for issues that might disrupt their supply chains and advises on how to mitigate them. Their insights inform clients’ decisions on siting new facilities, sourcing crops, purchasing insurance, and adapting to climate change. In the U.S., those decisions could disproportionately affect the Midwest, which produces most of the nation’s corn and is projected to bear the brunt of rising temperatures in the years ahead.

“We’re interested in everything from start to finish. But one of the items that we’re very interested in is agriculture,” Davis says. “So, we monitor agriculture on a global basis virtually every day.” Among other things, that means following weather and crop reports.

Enter Logan Bundy who, as a college junior, reached out to Everstream in the hopes of landing work in its applied meteorology group. Davis took him on, promoting him from unpaid volunteer to intern to part-time consultant. Now Bundy clocks in at 4 am every weekday to help produce the company’s Agriculture, Energy and Supply Chain Digest before markets open.

Everstream introduced the budding meteorologist to agriculture and crop reports. With guidance from Davis and from his undergraduate adviser, Northern Illinois University meteorology professor Victor Gensini, Bundy began taking a closer look at those numbers.

“[Companies] are utilizing this corn crop condition data to make decisions,” explains Gensini, now Bundy’s Ph.D. adviser and coauthor of the Agronomy Journal study. “So, the natural question becomes: If this is driving your decision-making at a company that has clients that are interested in this information because of the economic impact of the changes in weather on corn, then we ought to look into that data a little bit more and understand its flaws and strengths.”

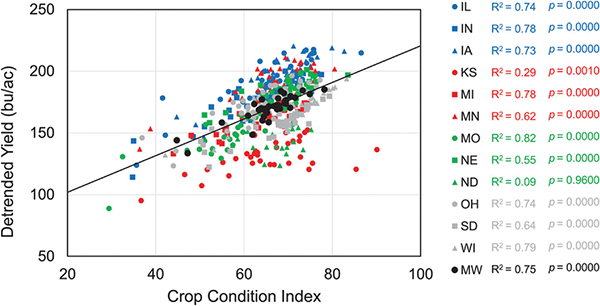

Bundy and Gensini collected June-to-September corn condition ratings from 1986 to 2020 and then converted them to crop condition index (CCI) values, a simpler number to work with. After detrending corn yield over that period to account for gradual increases over time, they ran statistical analyses. Among the most striking results: The annual average CCI values are an accurate predictor of state-level yield for all Midwest states except North Dakota. When factoring in the Peace Garden State, the predicting power is 75% for the entire Midwest—still pretty impressive.

“We, as meteorologists at least, get excited if we see anything above 0.4,” Bundy said. “But 0.75—I was actually really excited to see something that high because it confirms that—wow—these are actually pretty accurate when it comes to looking at yield.”

Bundy first set his sights on meteorology when, as a boy, he witnessed the wreckage wrought by a tornado near his central Illinois home. While he first foresaw a career as a forecaster like the ones he watched on the Weather Channel, Bundy has found his true calling with applied meteorology, at the nexus of agriculture and climate, he says. He enjoys seeing his work directly affect the lives of clients—in this case, validating the crop reports they rely on for big decisions.

“It reassures them that what they’re looking at is legitimate and can be for practical use,” Bundy says.

These days, in agriculture especially, such reassurance can be hard to come by. “There’s certainly a lot of uncertainty when it comes to the future impacts with climate,” he says.

Crop Reports and Climate Change

Bundy spoke to CSA News from his campus office in Lincoln, on a mid-April day when the high was 12°F above average. Nebraska was also in the clutches of a drought severe enough to prompt state lawmakers that month to earmark $53 million to build a canal ensuring future access to the South Platte River.

Against this background, Bundy discussed the statistically significant correlations he and Gensini discovered between corn condition ratings and climate indices for drought, temperature, and precipitation. July stood out as a critical month throughout the three decades of data: Weekly CCI values correlated most strongly with both detrended yield and climate variables that month and decreased at their highest rate.

“That’s a concern going forward,” Bundy says, “because July is a critical reproduction period for corn during pollination.”

But he and Gensini also found some encouraging news in the numbers. While optimal corn conditions declined over the 35 years of the study, overall yields rose.

“Even though the crops appear suboptimal,” Bundy says, “they may still yield well due to the advancements made in things like hybrids, breeding genetics, potentially the planting date, and then just overall management.”

The study, the authors say, provides a foundation for future investigations using this long-overlooked data trove. But it also highlights shortcomings that limit its utility. For example, although data are submitted at the county level, the reports provide only aggregated state-level data.

“Texas is a big state, Illinois is a big state,” Gensini notes. “These are broad geographies. If you want to really begin to pinpoint where the issues are, you need to have higher-resolution data.”

According to NASS Chief of Crops Branch Lance Honig, NASS is looking at changing how it collects this data and may one day rely more on satellites than humans. But for the foreseeable future, at least, people on the ground—many of whom have been collecting crop data week after week, year after year—will continue to provide the reports.

“The numbers are great, but the comparisons [across time] are better,” Honig says of the reports. “Right now, this is still the best way that we have and the most consistent.”

Gensini wants those reporters to know that, especially given the accessibility and quick turnaround of their data, they’re doing a great job.

“We demonstrated that this data can be useful,” Gensini says. “More than anything, I hope it demonstrates to these folks who are out there doing the hard work: Your data means something. Not only to us as researchers, but actually in the frontline for economics and to people who are making decisions about the potential for the future yield of corn.”

That’s no hollow compliment: Gensini and Bundy will soon be diving back into the crop reports to take a much broader look.

“We’re going to expand that to all field crops and for the entire United States that do the condition reporting,” Bundy said. “So, we’re basically going to do this [same] analysis, but for more crops and for a bigger area.”

Dig deeper

Check out the original article, “An Assessment of USDA Corn Condition Ratings Across the U.S. Corn Belt,” published Agronomy Journal: https://doi.org/10.1002/agj2.20973.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.