For the love of peat

Climate Crisis Can Be helped or hindered by peatlands depending on how we treat them

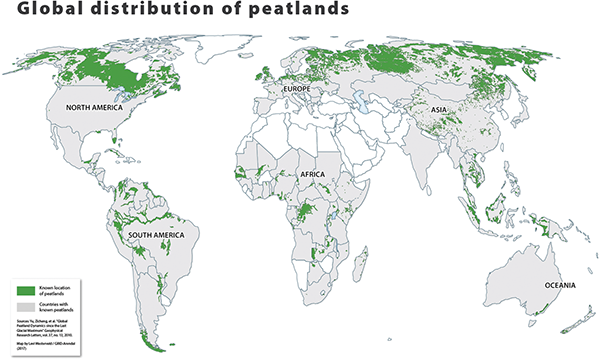

Peatlands cover only about 3% of the planet’s land surface but hold more carbon than all other vegetation in the world combined, sequestering some 0.37 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide each year.

Humans disrupt this carbon storage by harvesting peat for fuel and garden soils and clearing peat for agriculture, forestry, building roads, and other reasons.

When we degrade peatlands, we can turn them from a carbon sink to a carbon source. But if treated right (or left alone), they can help us solve our climate crisis by pulling carbon dioxide out of the air and storing it for centuries.

About 3% of the planet’s land surface is covered in peatlands. Yet those peatlands hold more carbon than all other vegetation in the world combined. When left to their own devices, peatlands sequester some 0.37 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide each year. That’s pulling carbon dioxide out of the air and locking it up. And they’ll continue to do so for thousands of years.

Unfortunately, we humans don’t tend to leave nature alone. In fact, says Nigel Roulet, an ecohydrologist and biogeochemist at McGill University in Montreal, there’s “overwhelming evidence that we screw up ecosystems” time and time again. That certainly is the case for peatlands. We harvest peat for fuel and garden soils; we clear the peat for agriculture, forestry, or even wind power uses; and we disturb peatlands inadvertently as we do other things, like harvesting oil and building roads, Roulet says. When we degrade peatlands, we can turn them from a carbon sink to a carbon source. A quarter of Europe’s peatlands, for example, are degraded because of human impacts. Though Europe has only 12% of the world’s peatlands, it produces 15% of global peatland emissions thanks to that degradation. Globally, damaged peatlands account for 5% of annual anthropogenic emissions of carbon dioxide.

And therein lies the quandary: Peatlands, if treated right (or left alone), can help us solve our climate crisis by pulling carbon dioxide out of the air and storing it for centuries, providing a cooling effect. Peatlands, if treated poorly (degraded or removed), will make the climate crisis worse by releasing excess carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Which way it goes is up to us.

Peatlands in a Nutshell

Peatlands are a type of wetland that accumulates thick layers of peat, which is partially decomposed organic matter. Bogs, fens, and some marshes and swamps are peatlands, meaning they are wet enough and deprived of enough oxygen that dead plants don’t decompose but instead accumulate into meters-deep layers of peat. This stores carbon (whereas plant decomposition normally releases carbon).

The most common type of vegetation in temperate and boreal peatlands—the bulk of all peatlands—is Sphagnum moss. The dominant peat-forming species in temperate and boreal peatlands is likely to be Sphagnum, says Pete Whittington, a peatland hydrologist and soil scientist at Brandon University in Manitoba.

Spongy live Sphagnum moss usually covers the top centimeter or two of a peatland, Whittington says. The 40 to 50 cm below that is usually partially decomposed organic peat litter, followed by often-meters-thick layers of more highly decomposed peat.

In Canada, which has between a quarter and a third of the world’s peatlands (secondmost after Russia) for a total of around 114 million hectares, peatlands are predominantly in bogs and fens. Russia also has extensive bogs and fens in its temperate, taiga, and permafrost areas. Bogs are peatlands with a high water table and no surface water sources—they’re rainfed. They’re shallow, found in low-lying areas, and are often described as “bowls full of peat and water.” Fens also have a high water table but can have a slow-moving surface water source as well. Though both are full of Sphagnum, fens often have more diverse flora as they tend to have more nutrients. On the surface, bogs and some fens look pretty similar, but their hydrology is pretty different, Whittington says. Tropical peatlands look and operate a bit differently from the higher-latitude peatlands.

Peatland Degradation

Concerns about peatland degradation center on how important peatlands are for the global carbon cycle. Given that damaged peatlands become a major source of carbon dioxide instead of a sink, it’s understandable to be concerned, Roulet says. Estimates suggest about 500 to 550 gigatonnes of carbon is locked up in peat. That’s about two-thirds of the carbon that’s in the atmosphere right now, he says. “The question is if we were to alter these systems through climate change and/or land use change, how much of that carbon would be returned back to the atmosphere?” Roulet wonders.

If much carbon were to be returned, the situation could get pretty dramatic pretty quickly; for example, when we burn peat for fuel (which some parts of the world still do), we take carbon that’s been locked away for thousands of years and release it immediately, creating a massive shift of that carbon back into the atmosphere, Roulet says.

Another quick shift occurs when we dig up peatlands for activities like installing seismic lines looking for oil in Alberta, Roulet says. Or building roads and powerlines. We take this moist peat that’s locked in a centuries- to millennia-long cycle, pull it out of the ground, and toss it into a pile where it dries out, decomposes a lot faster, and starts to quickly release its carbon. “These are what I call inadvertent changes,” Roulet says, “and in Canada, they far, far exceed any deliberate changes in peatlands.”

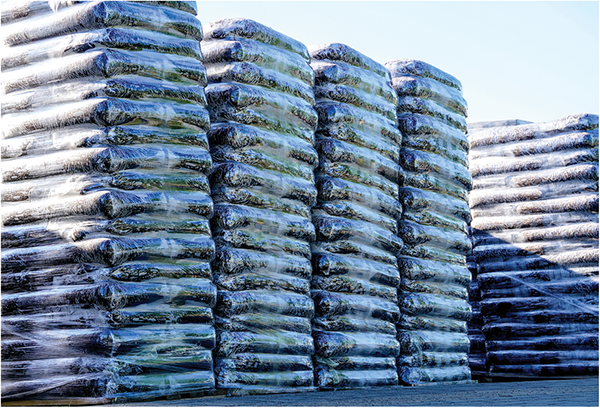

Deliberate changes—especially peat harvesting, which is a big industry in Canada and used to be a big industry in Europe—also play a role in degradation though what role exactly is hotly debated.

Peatland Harvesting

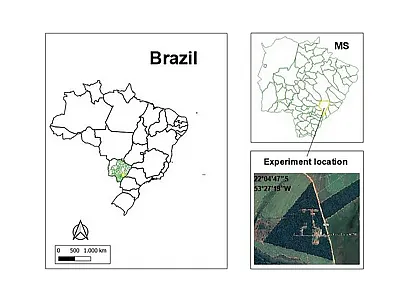

About 0.03% of Canada’s peatlands, around 34,000 ha, has been or is currently used for peat production. Canada produces about 1.3 million tons of peat each year, of which the U.S. imports 87%.

What happens to the peatland (and the carbon) once peat is harvested, and how much carbon is released by the peat that’s now being used for horticulture? The first is far easier to answer than the second, Roulet says.

In Canada, peat harvesters are required to restore the peatlands after harvest finishes. Research has shown that restoration, especially using the moss layer transfer technique—in which Sphagnum mosses are transferred from a donor site back into the harvested peatland—is very successful over time, Roulet says. And it’s a far shorter timeframe than we might think. Studies suggest that within two years of restoration, carbon is being sequestered even though there are still some emissions, Roulet and colleagues, including Kelly Nugent and Ian Strachan also of McGill, reported in Environmental Research Letters in 2019. By seven years, the restored peatlands no longer emit carbon, and by 14 years, “the systems seem to return to what they did before,” he says. These peatlands are self-regulating and good at what they do.

That said, however, Roulet adds, you need about 10 years of restoration to offset one year of emissions from the extraction. A typical peat field is harvested for about 20 to 30 years, he says, so you need about 200 to 300 years to reaccumulate all the carbon that was emitted while peat was being extracted.

How much carbon is being released by the peat that’s now being used for horticulture is a topic that is just starting to be studied, Roulet says. If peat is burned for fuel, 100% of the carbon is released into the atmosphere immediately. But how fast it decomposes and loses its carbon in gardens and greenhouses—peat’s primary use nowadays—is unknown, he says. It may be as little as 5% per year. Additionally, he adds, there’s an industry now devoted to collecting used horticultural peat and reusing it, adding a few more years to its lifecycle. What is clear, he says, is that extracted peat that is used for horticulture is not releasing its carbon into the atmosphere super quickly.

Whittington brings up another factor to consider: If we were to suddenly quit using peat in horticulture, what would we use instead? People talk about coconut fiber substrate as an option, he says. But if you look at the greenhouse gas impacts of harvesting that coconut from thousands of miles across the ocean and shipping it to North America, a quick back-of-the-envelope estimate suggests the impacts would be far higher than harvesting the peat that’s already here, he says. “If the environment is your concern, from a greenhouse gas point of view, it doesn’t make sense” to use coconut fiber instead of peat in North America, he says. “It’s worse for the environment. …[That’s why] it’s important to look at and talk about the big picture.”

The Impacts of Climate Change

Peatland restoration is also debated—and being actively studied—for climate change reasons. Some people want to restore peatlands and wetlands all over the world, even where perhaps they’ve been gone or damaged for decades or centuries.

But Roulet suggests that’s not going to be necessary. “We’ve done a lot of research on the sensitivity of that carbon pool [in peatlands] to climate change, and the evidence is pretty clear that, at least at the rate in which climate change is happening now, from an ecosystem perspective, like peatlands, the bogs are able to keep up.” That’s despite projected precipitation and temperature changes. Increased temperatures may increase evapotranspiration and dry out upper layers of bogs, thus increasing decomposition rates. Decreased precipitation could cause the same thing. Other areas, though, might see an increase in primary productivity and Sphagnum invasions, in which case, peat accumulation might increase. Either way, Roulet says, the research suggests the bogs, at least those in humid environments where fire is not as much of a concern, will be okay. Roulet and his colleagues recently released results (in Science of the Total Environment) of new models that consider climate change, microbial activity, hydrology, nitrogen and phosphorus ratios, peat substrate quality, and many other factors in peatland carbon release tracking.

For fens, though, the jury is still out, Roulet says. Fens are much harder to study because they have to be analyzed within the context of their hydrological catchments. Thus, fens’ responses to climate change—changes in vegetation, temperature, and hydrology, even such changes as whether precipitation falls as snow or rain and when in the season it falls—are unknown. In rough simulations so far, he says, researchers have found that about 50% of the time, fen ecosystems collapse with projected increased temperatures, but “we’re not confident” in that. Plant modeling and litter interaction are also too crude, he says. Much more research is needed. Going forward, Roulet says, “I think the focus should be on determining the stability of the carbon stored in peatlands.”

Another recent study, led by Whittington and published in the Soil Science Society of America Journal (https://doi.org/10.1002/saj2.20327), shed light on porosity and particle density of Sphagnum mosses in peatlands. The team found that Sphagnum litter density is about half the value used in most models. Such information is important for determining unsaturated hydraulic conductivity of the peatlands, which in turn affects carbon movement—storage or release. Understanding hydrologic changes and hydraulic conductivity is extremely important, Whittington says.

Whittington and his team also found that the variability of measurements using the volumetric method of measuring porosity—the standard measurement technique—is “enormous,” he says.

“[We found] there’s a lot more room for error,” says SSSA member Alex Koiter, a soil scientist at Brandon University and a co-author on the paper. “More places where things can go wrong.”

Whittington says he, for one, isn’t going to use that technique anymore. Each new study helps researchers “pick away at the unknowns,” he says. Models are sophisticated, but they’re only as good as their data. The more we know about how soils will be impacted by the new extremes of climate change, the better, Koiter adds.

There’s much more to be learned about how climate will affect these ecosystems, Roulet says, but “land use changes are the biggest threat for peatlands, and the biggest land use changes are the ones we don’t even consider. Peatlands may not be viewed as sexy, Roulet says, but they’re really important in the global carbon scheme. We can’t afford to mess this up, he says.

Dig deeper

View the original Soil Science Society of America Journal article referenced in this article, “Bulk Density, Particle Density, and Porosity of Two Species of Sphagnum: Variability in Measurement Techniques and Spatial Distribution,” at https://doi.org/10.1002/saj2.20327.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.