What you think about how soil and water health connect may be wrong

Agricultural runoff from surface and tile drainage is a significant problem in many watersheds, and the Great Lakes are a prime example. To varying degrees, the lakes have suffered from high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus, leading to fish kills, algal blooms, and loss of drinking water to millions of people.

Scientists have investigated ways to reduce these nutrient losses, including research on how management practices and other factors impact soil health and water health. But missing from this puzzle has been an understanding of the direct relationships between the health of soil and the health of the surrounding watershed.

In two recent studies in the Journal of Environmental Quality—both part of a special section on how the health of soil and of water intersect—scientists took on this demanding challenge. They came away with intriguing clues about the extensive interrelationships among soil, water, and on-site factors, but no strong evidence that our common soil health measurements predict water health. They did, however, find at least one way in which soil health can, in fact, undermine water quality.

It stands to reason, right? If you have healthy soil on your farm, you’ll have healthy water at the edge of your fields, too. It makes sense that water flowing over or beneath those fields will reflect the soil it passes through.

But according to a pair of recent papers in the Journal of Environmental Quality (JEQ), that may not be the case, at least not necessarily. Although the authors emphasize that they have just begun to tease out an incredibly complex web of relationships, their work serves as a caution against equating soil health with water quality.

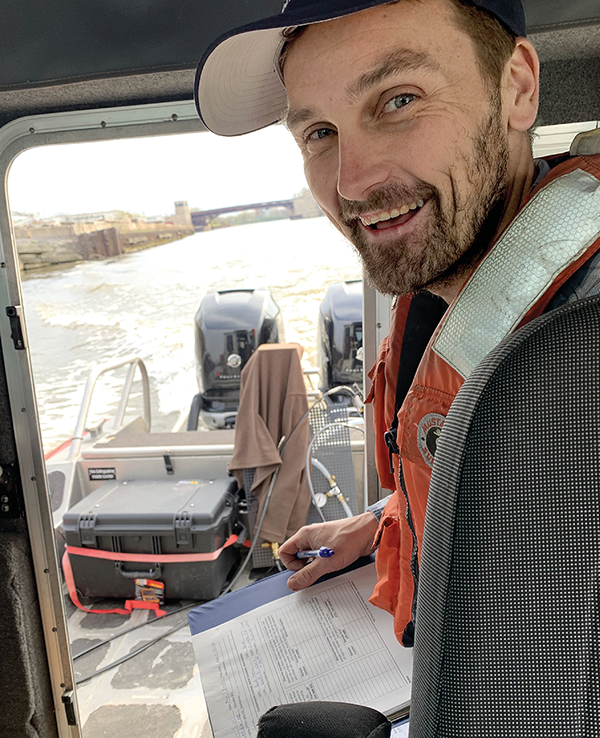

“I think we were hoping to see better soil equals better water,” says Luke Loken, a hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Madison, WI, and a co-author of one of the JEQ papers. “But that relationship is complicated.”

Will Osterholz, a soil scientist with USDA-ARS and lead author on the other JEQ paper, echoes Loken’s thoughts. “I feel like that’s a hopeful thing without a lot of actual data behind it.”

But these two research teams did analyze actual data from across the Great Lakes region, data as intriguing for what

they did not reveal as for what they did. Their papers are part of a special JEQ section, “Exploring the Soil Health–Watershed Health Nexus,” that grew out of a 2020 symposium organized by The Universities Council on Water Research and the University of Minnesota. The special section created an interdisciplinary space where researchers could begin to fill in gaps, previously occupied by assumptions, with data and knowledge.

“We’re hoping that the issue will show people that we have the potential to link across disciplines and to start some initiatives, to assess what data sets that we actually have that are already being collected,” says SSSA member Ann-Marie Fortuna, a USDA-ARS soil scientist in Oklahoma and lead guest editor for the special section. “Maybe this will start a conversation about how we can approach this multidisciplinary question of the nexus.”

Turns out that nexus is pretty gnarly, based on these first forays into the topic, and the JEQ authors are careful to manage expectations. Osterholz, an SSSA member with the USDA–ARS’s Soil Drainage Research Unit, describes his paper (https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20308) as a proof of concept—a “best first attempt” at cracking a complex nut. And University of Wisconsin–Green Bay soil scientist Kevin Fermanich is upfront about the effort in his paper’s title: “Challenges in Linking Soil Health to Edge-Of-Field Water Quality Across the Great Lakes Basin” (https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20364).

But the researchers didn’t tackle the topic because it’s easy; they tackled it because it’s urgent.

“Especially in wet years, well over 80% of the source of phosphorus in key regions of the Great Lakes is coming from agricultural land,” explains Fermanich, an SSSA member who uses sustainable practices on his own farm in northeast Wisconsin where he grew up. His home turf of Lake Michigan’s Green Bay has been particularly hard hit by excess nutrients. “If we’re going to meet our goals of water quality improvements, reductions of those losses across these watersheds are really critical.”

Is the Evidence Hard to Find, Or Just Not There?

People didn’t always care about soil health. Not because they were ignorant or callous about soil’s fundamental role in crop production. Rather, soil health, as a scientific concept, is relatively recent, Osterholz explains.

“It really started around the late 1990s, with the concept of soil quality, and has morphed a little bit since then,” says Osterholz, a guest editor for the special section. “This idea of soil health has picked up a lot of steam in the last 10 years or so.”

In that time, scientists identified measures for soil health based on specific physical (such as compaction), chemical (nutrient levels, for example), and biological (microbial biomass) attributes and created assessment tools. Producers, researchers, and government agencies became more interested in the concept, many focusing on how to boost soil health in order to, in turn, boost crop production.

Soil scientists also examined how specific site factors—management practices, precipitation, and water flow—impacted soil health. Hydrologists and limnologists studied how those same factors affected edge-of-field (EOF) water quality. Often, these two groups worked along parallel but separate tracks.

But what would happen if you changed the geometry of the question, so that those lines intersected?

Fermanich wanted to give that approach a try. Throughout his 34-year career, he says he’s been passionate about what happens when water meets soil. In the study he led and co-authored with Loken and other researchers from the USGS, Purdue University, and USDA-NRCS, he examined data from 14 sites across five Great Lakes states to assess relationships among soil health indicators, EOF catchment factors, and surface runoff quantity and quality.

As someone who has studied this stuff for a while, Fermanich was not surprised by some of their findings. The team observed, for example, that carbon, phosphorus, and nitrogen levels tended to be similar within sites: If carbon was high, for example, P and N were also high. Also not surprising: If nutrient levels were high in the field, they were high in the water, too.

But more eyebrow-raising were the relationships they didn’t find. The team uncovered no significant links between soil health and runoff indicators of watershed health. There are several possible reasons why, the researchers say.

First, any links would be inherently hard to parse out, in large part due to the many factors, sites, and variables involved.

Second, their data set was limited. The 14 sites represented a wide variety of catchments, precipitation events, and farming practices, and the broad spectrum in measurements made it especially hard to pin down relationships.

“A lot of data is needed to tease out those relationships at the fine spatial scale we are working at,” Loken notes. “There’s a lot of variation in what we are measuring.”

Third, it’s possible relationships between soil and water health were present but obscured by the stronger effects of on-site factors. It was a bit like trying to smell the flowers near a field recently fertilized with poultry litter—an especially apt analogy, in this case.

“If the farmer puts on manure today, and it rains tomorrow, it may not matter what was happening [in the soil],” Fermanich explains. “Those site factors—slope steepness, timing of the rainfall, all that stuff—just bypass the soil. We’re trying to look at something that might be influencing only a small arc.”

Yet another possible reason no links were seen, Fermanich suggests, is that an effective measurement tool, model, or index for detecting them doesn’t yet exist. After all, soil health parameters weren’t created with water quality in mind.

“We don’t really have a good set of parameters that are linked to predicting water quality,” Fermanich says. “Often the soil health parameters are characteristics linked more to productivity of the crops, even though they often have some environmental thresholds. That’s where the science is really weak right now.”

A final potential explanation for why the team did not pick up any links is that soil health just doesn’t connect to water quality directly—a result many might find counter-intuitive.

The links may be there, or not, Fermanich says—the research is hard, and more needs to be done. Meanwhile, across the Great Lakes in Ohio, fellow soil scientist Osterholz has wrestled with his own complex data sets. The models his team used also didn’t uncover any links—with one notable exception. And that exception might require some people to rethink their assumptions about the soil–water nexus.

Can Soil and Water Health Be at Odds?

Osterholz encountered some of the same challenges as Fermanich, including the sheer complexity of the data. He and co-authors from the USDA and The Ohio State University juggled 18 parameters from 40 study sites in Ohio that drain into Lake Erie—the most nutrient polluted of the Great Lakes—for both surface and tile-drain water (Fermanich’s study focused on surface runoff). In the interest of keeping the study manageable, the team did not consider the impact of management practices.

The Ohio team also grappled with how to integrate data when sampling for water and soil can occur on such different spatial and temporal scales. Soil samples are collected at specific sites at fixed points in time; water is constantly flowing and changing, and samples are collected over longer periods of time. Connecting the disparate measurements proved a bit like fitting a square block into a round hole.

“I don’t think we’ve necessarily settled on the best way to do this,” Osterholz says.

Despite the challenges, the team crunched numbers and ran models. In the end, they found no strong evidence that soil health was associated with improved EOF water quality. But—and this is a pretty good “but”—they did find evidence that soil health was associated with degraded water quality.

Specifically, the team looked at the relationship between water-extractable carbon and nitrogen in the soil—a sign of soil health—and EOF nitrate losses—bad for the water. They observed that, for tile-drained fields, higher, healthier C and N levels were linked to more nitrate losses—and poorer water quality.

In other words, what was good for the soil turned out to be bad for the water, which creates something of a predicament, as Osterholz elaborates.

“A farmer, if he’s focused solely on soil health, would be happy if he was able to increase the amount of water-extractable carbon and nitrogen in his fields: That would mean he has a greater potential for microbial activity. Nitrogen and carbon are actively cycling in that soil, which would indicate a healthy soil. But the downside we saw in our data is that, in those fields that did have that greater water-extractable carbon and nitrogen, we also saw greater amounts of nitrate leaving the field through the tile drains, which is obviously a negative for water quality issues.”

Soil health does not equal water health might look like wacky math. Osterholz, however, who did his dissertation on nitrogen cycling, was not surprised by the finding. Neither was he excited, knowing it potentially pits soil health against water quality. But science doesn’t always align with convenience.

“There are these trade-offs that are out there and need to be recognized,” Osterholz says, “and haven’t yet been recognized by some of the people promoting soil health as a water quality solution.”

More microbes in the soil or fewer nutrients in the water? It seems like just another tough choice for producers balancing environmental stewardship with feeding the world.

“Nutrients are great at growing crops and algae,” Loken notes. “We have multiple goals to consider—growing food and keeping water clean. These two goals are often at odds with each other, and there are trade-offs to consider with any management decision.”

Plenty More Strings to Pull

The authors behind these and the other special section articles have pulled at dozens of strands in the complex soil–water health web. But there’s plenty more pulling to be done that could help inform high-stakes decisions on management practices.

“We spend millions of dollars on conservation practices,” Loken says. “Do we see improvements where we’re implementing those practices? That’s one of the main reasons for initiating this project from the USGS side of things.”

The study team is still collecting data at their Great Lakes sites and hopes longer-term studies will provide more insights. They are also looking at combining their data with other EOF data sets.

“I think we’ll get some better signals, or potential signals, related to some of the physical properties now that we have more years of data,” Fermanich says.

In his JEQ paper, Osterholz employs the phrase “more research is needed” numerous times. He is now following up on several of the tantalizing clues in the data. One involves aluminum levels in soils. The team observed that fields with greater aluminum concentrations tended to have greater surface discharge but reduced tile discharge. The finding could have important implications for nutrient loading because surface water carries more nutrients. “Those are the more exciting results,” he says, “things that you weren’t expecting to see. They pop out and they really get you thinking.” In this case, he’s thinking the issue may be related to soil mineralogy.

Osterholz is pursuing another intriguing finding on precipitation. Their models revealed that during large events, field slope was a more important predictor of phosphorus loss in tiles while for small events, ammonium was the more important predictor. Given the bigger, more frequent rain events caused by climate change, Osterholz wants to tug harder on this particular string. The ammonium may come from historic manure applications, he hypothesizes.

Like Fermanich, Osterholz and his colleagues are adding to their data—taking more frequent soil samples, for example, and looking for ways to marry their data set with others. Progress in understanding this complex nexus depends on precisely this kind of cooperation, says Kevin King, one of Osterholz’s co-authors and research leader at his USDA-ARS unit.

“I believe that when we face some of these tough challenges, such as the recurring harmful and nuisance algal blooms in Lake Erie, bringing together different scientific perspectives and disciplines is essential,” King says, “not only to identify the underlying issues, but also to offer and explore different potential solutions, and ultimately come to faster scientific discovery and understanding.”

Dig deeper

A number of the articles from the special section, “Exploring the Soil Health–Watershed Health Nexus,” in the Journal of Environmental Quality are available on the Early View portion of the website at https://acsess.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/15372537/0/0. The two specific papers mentioned in this article are:

“Challenges in Linking Soil Health to Edge-Of-Field Water Quality Across the Great Lakes Basin: https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20364

“Connecting Soil Characteristics to Edge-Of-Field Water Quality in Ohio”: https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20308

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.