Shedding light on manuresheds

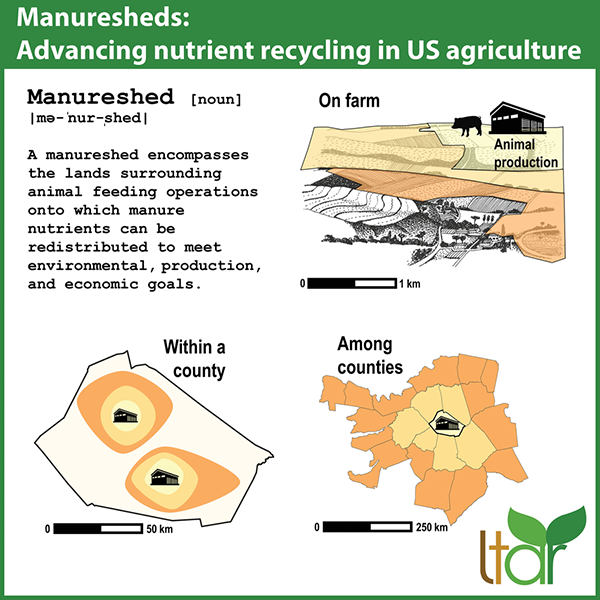

A riff on the term “watershed,” the recently coined “manureshed” refers to the crops and other land around a livestock operation that could use the nutrients from the animals’ manure, creating a circular nutrient system.

In a new Journal of Environmental Quality special section, 11 research teams explore the complex array of issues related to manureshed research and management.

Here, we discuss the concept generally, highlight challenges to collecting accurate livestock data, and study some examples, including a “mega-manureshed” stretching across the southeastern United States.

The adage “Use it, don’t lose it” can apply to lots of things. Practicing an instrument, for example. Staying fit. Redistributing animal poop.

OK, so maybe that last one wouldn’t be at the top of everyone’s mind. But livestock manure is chock full of nitrogen, phosphorus, and other goodies that plants need. And if those goodies aren’t put to use, they are lost from the nutrient cycle, turning from nature’s fertilizer to environmental threat. Yet that’s exactly what happens at farms across the globe where ballooning dairies and swine and poultry farms make it harder to get manure from source to sink.

Scientists have taken notice and are working to shed light on the problem through the concept of “manuresheds,” a term coined several years ago by researchers at Penn State University. A watershed is an area that drains into a specific body of water. Similarly, a manureshed is the region surrounding a livestock operation that can absorb the manure produced by those animals.

The goal of manureshed science is to reestablish a circular nutrient system—a closed loop for poop, if you will. The compelling construct has been embraced by the USDA and inspired a special section in the Journal of Environment Quality. USDA researchers Sheri Spiegal and Peter Kleinman teamed up to guest-edit the project.

“Coming from a background of watershed science, I am very attracted to the concept of a shed as an organizing framework,” says Kleinman, an SSSA and ASA member and soil scientist with the USDA-ARS Soil Management and Sugarbeet Research Unit in Colorado. “It could be the watershed, an air shed, a food shed. It implies a gradient, but it also implies a natural organization within which you can perform science. And that’s indeed what we’re putting forward here.”

The special issue comes at a time when farmers and policymakers are more motivated than ever to reconnect crop and livestock systems. They’re concerned about historically high fertilizer costs, a shrinking supply of phosphorus for making fertilizer, and the environmental and public health impacts of amassing tons of manure near livestock operations.

Working against these drivers are a slew of obstacles, from transportation, storage, and marketing challenges to farmer concerns about pathogens, odor, weed seed, and nutrient content and density. Manureshed science addresses the complex issues surrounding the disparate types of manure in an era in which “zero-acre farms” are a thing. This article discusses a few of them, including the hunt for relevant data and the challenges and opportunities of rebalancing sources and sinks near dairies and farms across the U.S.

“This special section is the first step for showing the complexity of the issues that we’re all facing as a society when it comes to uneven distribution of manure, nutrients, and potential solutions,” says Spiegal, who studies range management with the USDA-ARS in New Mexico. “It shows the breadth and depth of those kinds of challenges and solutions, all in one place.”

Compiling the special section was far from easy. As it turns out, restoring equilibrium in manuresheds has as much to do with balancing the interests of scientists and farmers as it does with balancing sources and sinks.

“Oh, man!” says Spiegal, who co-authored four of the special section articles. “The data wrangling and the cleanup is really half the battle.”

Dark Gaps and Shots in the Dark

Although scientists need data to study manuresheds, some farmers resist sharing information they consider private. They may also worry that volunteering an inch of data today will lead to demands for a mile’s worth later on.

“There’s obviously a lot of fear of potential regulation from the agricultural community in divulging information about their operations and that it may lead to more stringent regulations,” says Eric Booth, an associate research scientist in Agronomy and Civil & Environmental Engineering at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “But at the same time, this is a really important piece of information in order to plan larger-scale strategies. Without that information, we are kind of shooting in the dark.”

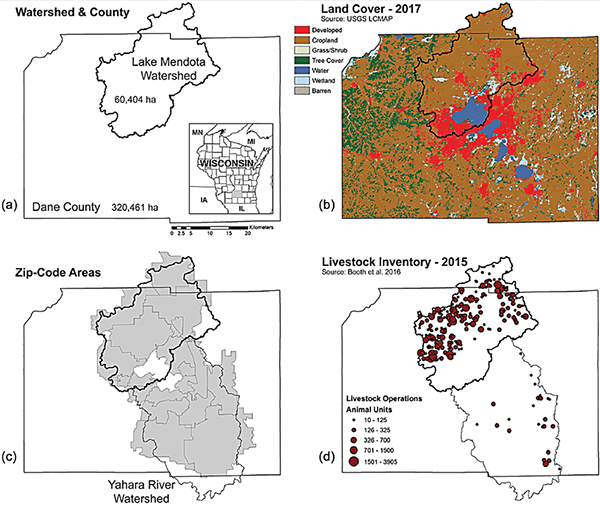

Booth, an ASA member, did a lot of shooting—and missing—while researching manuresheds in southern Wisconsin. It’s not that information on livestock isn’t available: It is. But it’s typically county-level data that doesn’t align with the study area. That, according to Booth’s paper, can lead to bad data.

Booth sought to quantify the livestock population in the Lake Mendota watershed using two methods. First, he used county-level data, which he downscaled based on how much of the watershed sat within that county; it’s a workaround researchers use when more granular data is unavailable. But inherent in the approach is the problematic assumption that livestock are distributed evenly across a county, like so many trees in an orchard. Inconveniently, this tends not to be the case.

“If animals were spread out evenly across the county,” Booth mused, “it would just be logistically easier to balance crop needs and manure production.”

In the second approach, Booth unearthed livestock data from the Census of Agriculture that he could slice and dice by ZIP code, resulting in a more accurate approximation of the watershed boundary. Comparing the two methods, he found a big difference. In 2017, for example, the livestock inventories and associated manure production calculated using the ZIP code method were more than 150% higher than those derived from county-level data.

Clearly, Booth argues, sub-county scale data are needed to accurately delineate manuresheds.

“In an ideal world, we would have great information at the operation scale,” Booth says, “not only in the number of animals, but also management practices of how that manure is collected and applied. Because those are also pieces of information that are important to assess environmental risk.” Some states are more ideal than others. In Iowa, for example, data are available on a more granular level, a model other states could follow, Booth says.

And while satellite technologies have successfully probed other areas of farming, animal populations remain something of a “dark gap,” according to Booth. “Just how many [animals] are in a given location and how much manure they’re producing in a certain area—it’s just something that we can’t see as well from satellites.”

All the more reason to share the data we have on earth, according to Booth, who can envision how that cooperation could benefit stakeholders such as county soil and conservation departments.

“They could look and see where there might be more manure produced in an area than what the land could reasonably assimilate,” he says. “Then, maybe, in another part of their county, they see that they’re purchasing a lot of fertilizer, and maybe they could replace some of that with manure. Then they could bring those groups together and help facilitate agreements to share those nutrients.

“But without the data and a really good inventory of what’s out there, they are limited with what they can do, and they’re not able to make adequate decisions.”

Manuresheds in Action

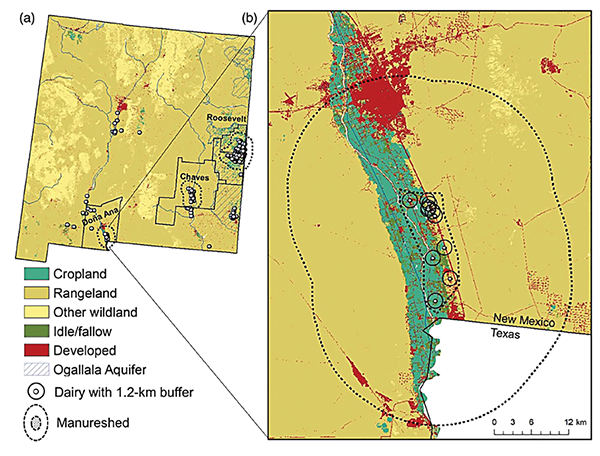

Although stakeholder cooperation is far from universal, successful examples do exist, as Spiegal outlines in a special section article focusing on another corner of the country: New Mexico.

From her homebase at the Jornada Experimental Range in Las Cruces, Spiegal studied how dairy farmers in the region cooperated with neighbors to distribute manure on rangeland and cropland. Thanks to these informal networks, nutrients in the three manuresheds she and her co-authors examined were generally balanced. However, development pressures and competition for water are slowly changing how land is used there, threatening this balance. As nearby sinks for their manure start disappearing, dairy farmers will have to transport their manure farther and farther, diminishing profits.

Land use changes also threaten harmony among the landowners on whom those successful manuresheds depend, Spiegal noted. “The shift from cropland to different types of land can erode some of those relationships required for these transfers,” she says.

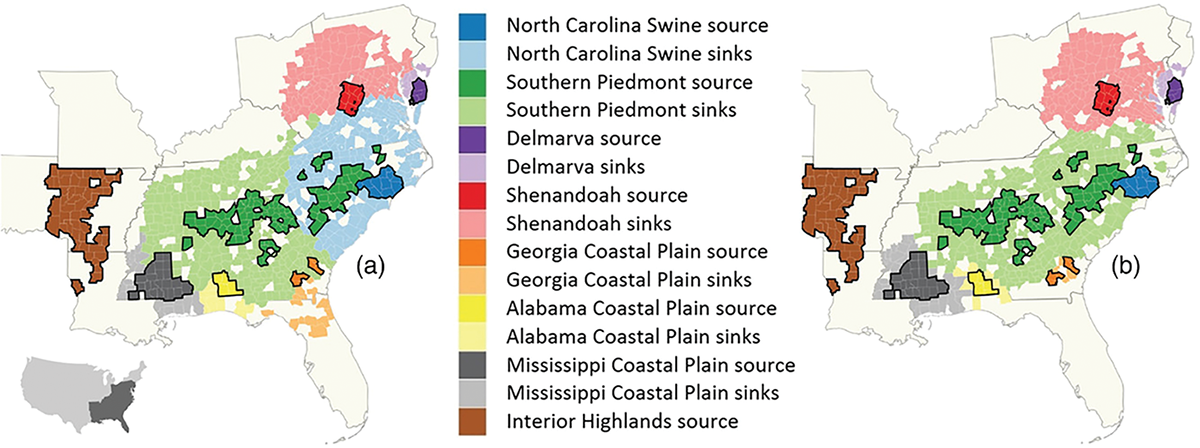

Across the country, another manure-producing industry is undergoing more rapid change. In fact, the magnitude of poultry operations across the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern United States—home to 55% of the nation’s poultry—has stretched the concept of manureshed so much that a new term has emerged to describe it. The so-called “mega-manureshed” is a result of the nation’s growing appetite for eggs, turkey burgers, and chicken nuggets.

“Poultry is one of your cheapest forms of meat,” explains Ray Bryant, an ASA and SSSA member and soil scientist with the USDA-ARS Pasture Systems & Watershed Management Research Unit in Pennsylvania. “And for that reason, the poultry industry is still expected to grow over the next decade.”

In a special section paper focusing on poultry, Bryant and his co-authors describe how the industry is uniquely suited to leverage the manureshed concept. For starters, thanks to its history of vertical integration, the industry already features the infrastructure and stakeholder cooperation that make manureshed management easier to implement. That checks off two big boxes.

In addition, poultry manure is drier than other types, which means better nutrient density and cheaper transport, and includes micronutrients not found in other manures. It can also be processed into more palatable pellets, making transport, storage and application more convenient. Paving the way for new applications such as sports fields, pelletizing also illustrates the innovation typical of the industry, Bryant said.

“Somebody who’s going to receive it would much rather be dealing with a bag of pellets than a bag of just poultry litter,” he says.

But with these advantages also come challenges. As with other types of manure, and in contrast to commercial fertilizer, it’s a bit of a guessing game as to exactly what nutrients (not to mention unwelcome hitchhikers like weed seeds and pathogens) are in any particular batch.

“There’s a lot of variability,” Bryant acknowledges. “So, if you want to do a really good job of nutrient management, you’d have to do a lot of testing to know exactly what you’re receiving and applying.”

Another nutrient issue is that the amount of phosphorus in poultry manure, compared with nitrogen, is higher than what crops need, Bryant says. That ratio becomes more problematic when you factor in the high phosphorus levels already present in much of the region’s soils—especially soils near swine and poultry barns—a legacy of decades of manure use.

A map in Bryant’s paper (shown above) paints a striking picture of the situation. It depicts a vast mega-manureshed, comprising seven regional manuresheds that stretch from Pennsylvania down to northern Florida, and from there west to the Arkansas–Oklahoma border. For each regional manureshed, the map shows the counties where manure originates as well as the much larger, surrounding area across which that manure would need to be spread to properly apportion its phosphorus. Within the Southern Piedmont, the largest manureshed, 93 counties, generated upwards of 37,000 tons of excess P. To reallocate it all, you’d have to drive up to 187 miles from the source and cover 235 counties.

The sprawling scope took Bryant aback. “I mean, I knew that there was a lot of poultry produced all across the Southeast,” he says. “But to think of it in terms of how many nutrients were being produced, and that it could totally satisfy the needs … in such a large area, I found surprising.”

Indeed, driving 187 miles to deliver a truck full of manure may not make economic sense, even for a business used to narrow profit margins. That’s why more innovation is needed to fix these broken nutrient cycles, says Bryant, who has been developing a filtration system to remove phosphorus from liquid dairy. “Without some kind of treatment, we’re just never going to be able to address the issue.”

The stakes, Bryant says, are considerable. He has watched eutrophication choke the Chesapeake Bay and sees excess N and P from agriculture threatening waters worldwide. “That goes from Lake Champlain to Lake Erie to the Gulf of Mexico,” he says. “It’s not only a continental issue: It’s a global issue.”

The Sharpest Tools in the Manureshed

Repairing the broken connections between nutrient sources and sinks across manuresheds will require a whole collection of tools, the experts say. Some will be science tools, like the research highlighted in the special section. A group of Australian researchers, for example, found that applying composted manure with some N fertilizer resulted in 9 to 90% less greenhouse gas emissions than using unprocessed manure.

While that’s encouraging, the program wasn’t economically viable, pointing to the fundamental role of economics to successfully manage manuresheds. “It’s the business model that is the real challenge,” guest editor Kleinman says.

Scientists help by studying those models and how they’re impacted by issues like standardization, transportation, quality control, changing regulatory conditions, and a supply that often outstrips demand. “You can saturate the market very quickly with manure,” Kleinman notes. “It’s just not gold.”

Success may depend on the willingness to toss out lots of manure ideas and see what sticks to the barn wall. “The manureshed has to be open to every solution that’s out there,” Kleinman says. Innovation, such as newfangled barns with manure processing built into their designs, will be key.

But it will be just as much about changing minds as changing practices, rebranding methods from socially unacceptable to socially laudable.

“We’re trying to elevate [manuresheds] to the level of a virtue,” Kleinman says. “It would be great someday to see that recognition translate to certification programs and to public awareness.”

Kleinman has faith in “someday” and with good reason. In the early 2000s, as a young scholar and father, he began working at Penn State on manure injection systems, a nascent technology that was gaining no traction. For years that stretched into decades, he and colleague Doug Beegle chased grants, tested ideas, wrote papers, engaged stakeholders, and watched as consensus around the systems began to build.

Last year, Kleinman was enjoying a long, springtime drive through the Pennsylvania countryside with his now adult children. He saw one manure injection system. A while later, he spied another. Eventually he spotted a third, a fourth, a fifth, his spirits lifting with each one. “That was 20 years in the making,” he says.

“Change can be very, very, very slow,” Kleinman reflected. “But when you do go out, and you see voluntary adoption and use of these technologies in the field, that means that you’ve made it through an incredible gauntlet of barriers to adoption.”

He and fellow guest editor Spiegal are betting on the same success for manuresheds. As a next step, Spiegal is leading a manureshed working group that is outlining plans for future work in farm communities that can benefit from this holistic approach.

“[The manureshed concept] definitely brings together all kinds of different topics,” Spiegal says. “It integrates all of these things that people really care about, like the sustainability of agriculture.”

Dig deeper

All of the articles from this special section, “Manuresheds—Reconnecting Livestock and Cropping Systems,” will be available in the July–August 2022 issue of the Journal of Environmental Quality by late July at https://acsess.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/15372537/2022/51/4. The specific papers mentioned in this article are:

- “Data Inaccessibility at Sub-County Scale Limits Implementation of Manuresheds” by Booth, E.G., & Kucharik, C.J.: https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20271

- “Poultry Manureshed Management: Opportunities and Challenges for a Vertically Integrated Industry” by Bryant, R.B., Endale, D.M., Spiegal, S.A., Flynn, K.C., Meinen, R.J., Cavigelli, M.A., & Kleinman, P.J.A.: https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20273

- “Land Use Change and Collaborative Manureshed Management in New Mexico” by Spiegal, S., Williamson, C., Flynn, K.C., Buda, A.R., Rotz, C.A., & Kleinman, P.J.A.: https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20280

- “Environmental and Economic Trade-Offs of Using Composted or Stockpiled Manure as Partial Substitute for Synthetic Fertilizer” by De Rosa, D., Biala, J., Nguyen, T.H., Mitchell, E., Friedl, J., Scheer, C., Grace, P.R., & Rowlings, D.W.: https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20255

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.