Growing with the seasons of life as an agronomist

Paul Carter is a former professor and extension agronomist, University of Wisconsin-Madison; senior agronomy manager, Corteva Agriscience (Pioneer); Fellow, ASA and CSSA

Prompted by requests to share thoughts as a panelist and mentor at various Society student sessions, I compiled a list of observations and suggestions for fulfillment and success for today’s agronomists and crop/soil scientists. I developed this list over the decades based on a long career as an agronomist and crop research scientist in both academia and industry:

- Grow with the seasons of life

- Turn disaster into opportunity

- Enjoy the opportunities in the moment—regardless of the outcome

- Publish your science and your perspectives

- Find mentors and networks

- Ask lots of questions

- Develop a thick skin

- Be willing to do what needs to be done that no one else wants to do

- Lead and collaborate without formal authority

- Avoid comparisons with others

- Enjoy time for relationships, family, home, clubs, religious/spiritual activities, and hobbies

- Ask God to bless the fruits of your labor

My hope is that this article stimulates other later-career Society members with other backgrounds to add their perspectives and story in a regular CSA News Emeritus and Retired (but still active!) Members column. Email Send Message.

I’ll use the rest of this article to talk about the first item on my list: Grow with the seasons of life.

Growth Stages

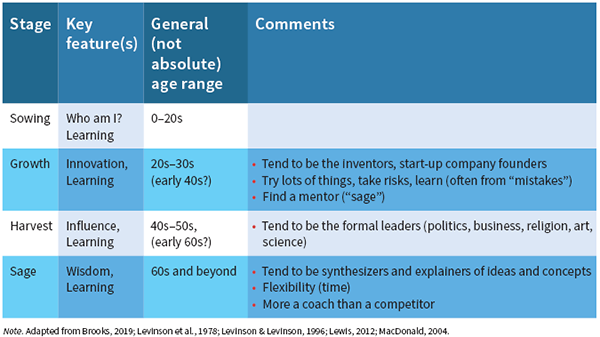

Over the years, I have encountered several books and articles that—along with my own experiences—that I gleaned and adapted using crop growth terms into “seasons of life” for people, especially those who are agronomists and crop scientists (Table 1) (Levinson et al., 1978; Levinson & Levinson, 1996; McDonald, 2004; Lewis, 2012; Brooks, 2019; Biehl, 2020).

Table 1. General “seasons” for agronomists and crop/soil scientists.

One can and needs to be sowing, growing, harvesting, and sharing wisdom as outlined in Table 1 at all phases of life, but the features listed in the table for each tend to be dominant (Brooks, 2019).

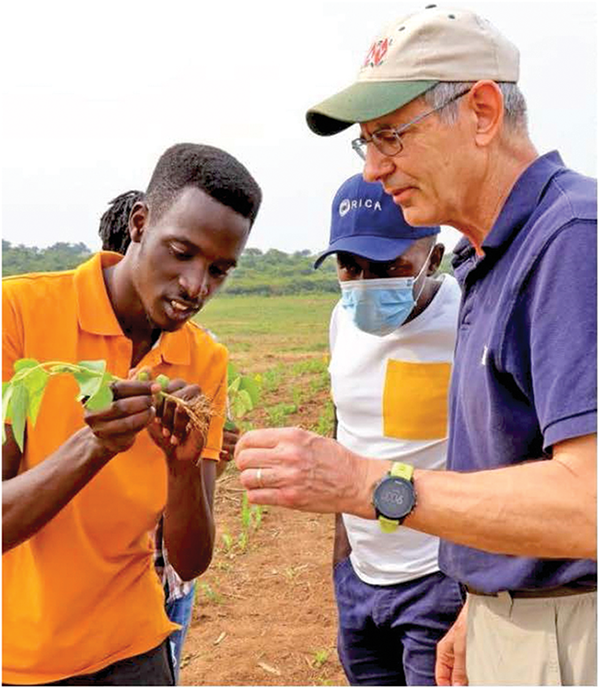

With this in mind, I have urged students or new hires not to get impatient in the “Sowing” and “Growth” stages, expecting to immediately be an industry manager or senior executive, for example. This is the best time to seek out a wide array of experiences and opportunities, take some risks, and find someone in the “Sage” stage for a mentor. All people have influence, but there are good reasons most senior leaders and managers in organizations tend to be in their 40s and 50s. And folks in those roles need to provide venues to hear the innovative and fresh ideas that tend to flow abundantly from those in their 20s and 30s (Brooks, 2019).

After several months as a recently hired assistant professor and state extension agronomist/crop specialist at a land grant university, I returned to the similar neighboring university where I had earned my M.S. and Ph.D. in agronomy for a visit. There, one of my internationally highly regarded research and teaching mentors asked, “How is it was going?” I shared that it was going well with good affirmation from extension educators and farmer leader clients but with intense on-the-job learning. He shared that it took about eight years before being comfortable and confident teaching and giving extension presentations from a position of both sharing the work of others and first-hand experience. Those were encouraging words, and his timeline assessment proved accurate for me.

These stages and thoughts are over-simplified and must not be taken as absolute—especially the exact age ranges. Also, a formal job title does not necessarily mean that the growth stage automatically comes with that title. Today I’m aware of tremendous extension agronomists and crop scientists in their mid- and upper 40s who are “new” assistant professors or research scientists—and their savvy from experience may provide greater or prominent influence more quickly than those with similar titles at traditionally younger ages.

Personal Examples

Here are two family examples showing that age is not an absolute with regard to a growth stage or title:

- My still-creative brother is an agricultural entrepreneur starting a new business in his mid-60s—but he leads with considerable focus on partnering with and building in innovation, technological savvy, and leadership of the generation of family in their 20s and 30s.

- My cousin’s wife recently received her lifelong dream of completing medical school and becoming a family practice medical doctor in her upper 50s. During her pursuit of an M.D., she used her years of experience as a physician’s assistant to mentor her son, who was also in medical school.

To use an analogy from my athletic background, it is instructive and liberating for me in career and life planning to be reminded that folks my age often tend to contribute most as synthesizers and explainers of ideas and trouble-shooters—as “coaches” and not as “competitors” (Table 1) (Lewis, 2012; Brooks, 2019).

Agronomic-related organizations (university teaching and industry research departments, start-up agricultural companies, etc.) would do well to access such insight from senior people, and I am aware of several that do so. One of my roles the final five years in a large agricultural company was providing integrated cropping systems input, working with innovative “millennial” data scientists to help drive practical crop modeling and sensor applications. It was a good match.

The Biggest Professional Mistake

Brooks (2019) expressed that “The biggest mistake professionally successful people make is attempting to sustain peak accomplishment indefinitely.” And Lewis (2012) says “what worked well professionally in one’s 20s and 30s may not work as well in one’s 60s”.

Over time, we need to change where we place our sense of identity and relevance—moving emphasis from professional achievements and accomplishments to more focus on mentoring, service, relationships, and religious/spiritual pursuits while still exploring new things or pursuing old things in new ways, as we prepare the next generations. (And, in my mid-60s, I am seeking professional mentor ideas from those in their late 70s and 80s.)

When one retires from full-time employment, the flexibility to contribute more to family support (parents and grandchildren) and fun time, hobbies, travel, etc. is appreciated and important. It is also a good time to screen our activities with the question: “how am I finding ways to both learn from and share what I have learned with those in our agronomic professions who are in the sowing, growth, and harvest stages?”

Members Forum is a place for ASA, CSSA, and SSSA members to share their opinions and perspectives on any issue relevant to our members. The views and opinions expressed in this column are not necessarily those of the publisher. Do you have a perspective on a particular issue that you’d like to share with fellow members? Submit it to our Members Forum section at news@sciencesocieties.org. Submissions should be 800 words or less and may be subject to review by our editors-in-chief.

Dig deeper

Biehl, B. (2020). Decade by decade. Aylen Publishing.

Brooks, A.C. (2019). Your professional decline is coming (much) sooner than you think. The Atlantic, July 2019. https://bit.ly/3y1tG5P

Levinson, D.J., Darrow, C.N., Klein, E.B., Levinson, M.H., & McKee, B. (1978). The seasons of a man’s life. Knopf.

Levinson, D.J., & Levinson, J.D. (1996). The seasons of a woman’s life. Knopf.

Lewis, R. (2012). Seasons. In A man and his design (Vol. I, pp. 91–98). https://app.rightnowmedia.org/en/content/details/211n

MacDonald, G. (2004). A resilient life: you can move ahead no matter what. Thomas Nelson.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.