Offsets, insets, carbon markets

Incentivizing Farmers to Improve Soil Health, Sequester Carbon

- Agriculture is a major factor in the Biden Administration’s plan to greatly reduce greenhouse gases, but how can we create a system that works for both producers and the many other entities interested in carbon sequestration?

- Carbon sequestration is tied to soil health, and soil health is incentivized differently based on relationships among producers, government programs, nonprofits, and third-party organizations.

- Here, we’ll take a look at the landscape of soil health incentives, from government conservation programs to non-profits, inset practices, and carbon market offsets.

The Biden Administration set a steep target: reduce greenhouse gases by 50–52% compared with levels in 2005.

The White House aims to encourage carbon capture across the economy while creating jobs. The administration wants to see “farmers using cutting-edge tools to make American soil the next frontier of carbon innovation,” a press release from 23 Apr. 2021 states.

Soil health is top-of-mind for many ASA, CSSA, and SSSA members; we’re always thinking about ways to improve soil, increase carbon capture, and protect an invaluable natural resource. But how can you bring farmers on board, helping them adopt conservation practices that improve carbon sequestration while still remaining economically viable?

The landscape of soil health incentives—monetary and otherwise—is complex. There are government-funded programs that have existed for decades, nonprofit organizations educating farmers and providing funding for conservation practices, and newer concepts like carbon markets and offset programs that are really picking up steam.

In all cases, the ability of an incentive program to connect with farmers relies on relationships. Government programs rely on extension, nonprofits turn to field days and conferences, businesses with agricultural ties turn to their stakeholders, and organizations without direct agricultural ties turn to a broker who does.

The Old Guard

The USDA has a portfolio of programs with funding allocated by the farm bill (most recently passed in 2018). According to the USDA Economic Research Service, projected spending on

conservation programs from 2019 to 2023 will top US$29.5 billion. Producers receive that money through their participation in two broad types of programs: those designed to increase sustainability on working land and those designed to remove unproductive agricultural land for more sustainable uses.

Of the six programs in the USDA portfolio, the two biggest spenders are the working land programs—the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP)—which account for about 50% of the total budget. Coming in just behind is the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), which allocates just over 35% of the remaining budget to programs designed to remove unprofitable land from production.

As of April 2021, the USDA opened enrollment in CRP with higher payment rates and new incentives in an effort to meet the climate goals set by the White House. In short, the USDA administers the program through the Farm Service Agency, which compensates CRP participants for taking agricultural land that is less productive than the rest of their fields—the land that may cost them money in inputs and labor—and using it for something else. That may be planting trees, growing perennial grasses, or grazing without tilling. The farmer increases their profitability by removing costly portions of land, sequestering carbon, and diversifying the ecosystem in the process.

The program enrollment process varies by state, North Dakota agronomist Lee Briese explains. He has a unique perspective—though based in ND, he works extensively with the South Dakota Soil Health Coalition, as well.

“For South Dakota, you have two different people working on the programs for NRCS, for example. A program person might come out and help you build the program while another person will come look at the regulatory side of things,” says Briese, who is a member of the Societies and a CCA. “Because the South Dakota Soil Health Coalition has a good relationship with NRCS in terms of funding, support, research, and implementation, there’s a lot of trust from farmers. They [NRCS] stepped up and built a bridge. It’s not that way everywhere.”

Briese touches on a topic that makes producers “twitchy”—that in the process of adopting positive conservation programs, they might also be checked for compliance in other practices that are federally regulated. In South Dakota’s case, the Soil Health Coalition is a non-profit, producer-led organization that helps farmers implement the “Five Principles of Soil Health”: Soil cover, limited disturbance, living roots, diversity, and integrating livestock.

“It’s like calling Habitat for Humanity to help you come build a house,” Briese says. “It’s what they’re there for, and it makes things a whole lot easier.”

The Role of Nonprofit Organizations

This brings us to the next sphere of soil health relationships: nonprofits. Nationwide, these groups organize educational programs, research and develop new technologies to help producers implement practices, and advocate for farmers’ interests in policy development.

In some cases, nonprofits have their own programs that incentivize farmers to adopt sustainable practices. Pheasants Forever, for example, works much like the CRP in that it helps farmers find unproductive parts of their land and convert it into thriving habitats for those ever-popular game birds, pheasants. In the process, they improve biodiversity and make desirable homes for other critters and give farmers an additional opportunity for income from hunting. Plus, Pheasants Forever uses the services of farm bill biologists to help educate landowners about the benefits of conservation programs and wildlife ecosystems.

In a different vein, the Soil Health Institute (SHI) is a non-profit that completes scientific research and advancement, identifying gaps in the research and then filling them. The group’s recent work in Agronomy Journal (AJ) showed, through interviews with 100 farmers, that soil health management systems aren’t just good for the environment, but also good for a farmer’s pocketbook. For the study participants, adopting soil health practices increased net farm income by $127 ha–1 for maize and $110 ha–1 for soybean (www.doi.org/10.1002/agj2.20783).

“We’re really here to enable farmers to reap the benefits of soil health practices, and that comes down to our need for certainty and our ability to measure soil health outcomes,” says SSSA member Dianna Bagnall, an SHI research soil scientist and first author on the AJ paper. “Soil health is complex, and when people want a direct measurement for soil organic carbon, we can measure it quite accurately. But the numbers can change across a field and with soil depth, and if you want to go out and manually measure it, well, it takes a lot of time, a lot of cost, a lot of transportation to run samples back and forth from the field to the lab.”

To meet that challenge, SHI is piloting a new tool involving a vehicle with a probe built in that can take instant SOC measurements. It could greatly reduce the amount of time it takes to measure soil carbon, providing literal “ground truthing” for estimates of carbon sequestration that are commonly made through modeling.

But that’s just one part of a solution to a very complicated problem. Without a well-developed, standardized means of quantifying “healthy” soil over large scales, groups are coming up with their own metrics for what it means to be sustainable.

A Vested Interest

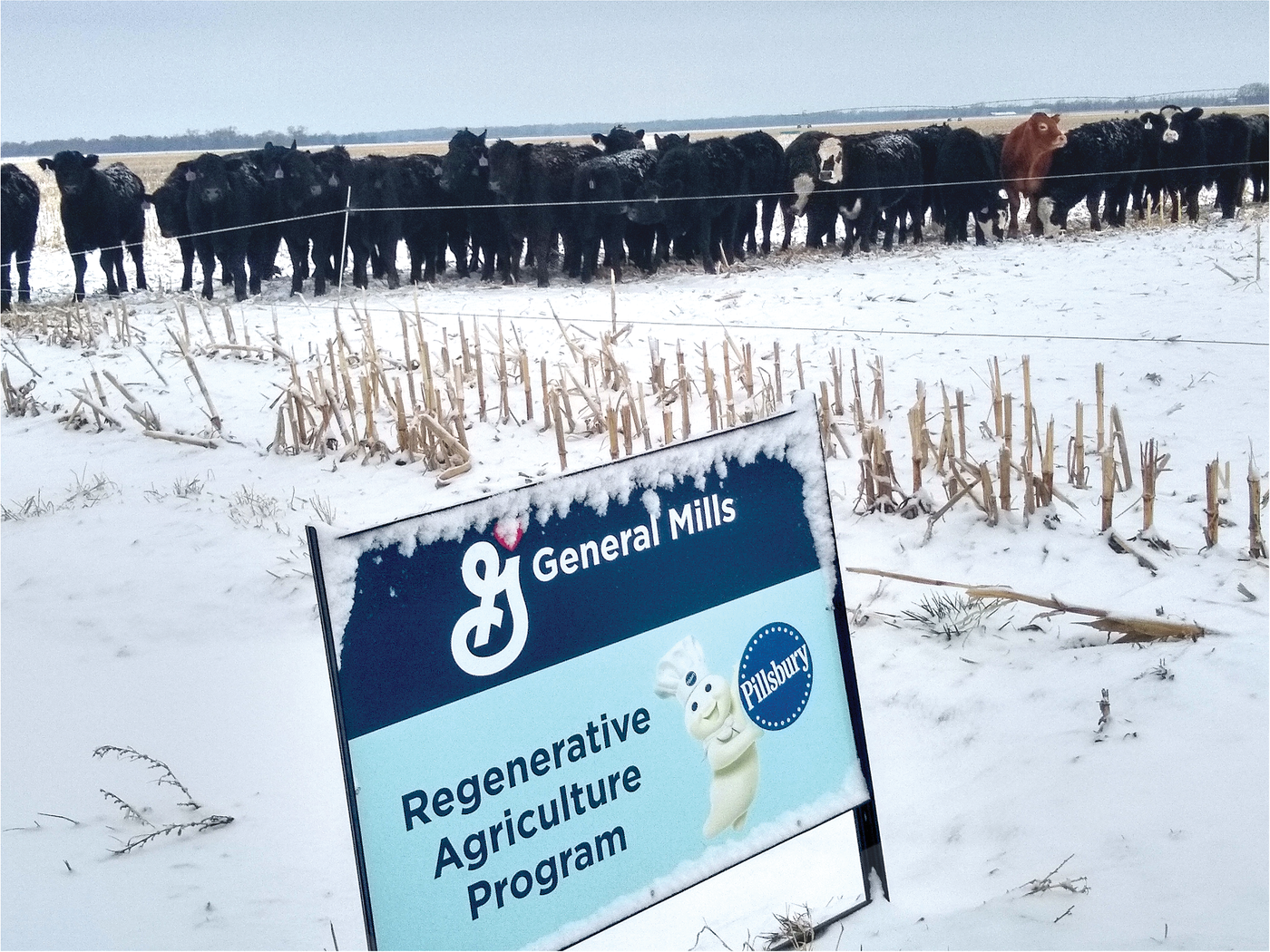

For companies with direct ties to producers, the easiest way to increase the sustainability of their production system and decrease their emissions might be working directly with their farmers. Here, companies look for practices within their own supply chains that they can modify to reduce their emissions, rather than “offsetting” their footprint by paying for carbon sequestration in a different sector.General Mills, for example, relies on oats, wheat, dairy, corn, sugar beets, and other agricultural products for the foods they produce. They set a goal to advance regenerative agriculture on one million acres of farmland by 2030, measuring impacts on five different aspects of the farm ecosystem. These measurable impacts include economic resilience in farming communities, soil health, water, biodiversity, and the well-being of dairy cattle in livestock operations.

“We’re really trying to understand the intrinsic, internal incentives that motivate farmers to implement regenerative systems,” says Steven Rosenzweig, a soil scientist for General Mills and an ASA and SSSA member. “We have a pretty good idea about the principles farmers can employ to improve environmental and economic outcomes, but it’s a matter of enabling farmers to adapt those principles to their unique context.”

Rosenzweig is looking for ways to help farmers implement these sustainable systems. General Mills is offering opportunities for farmers to innovate by cost-sharing for inputs like cover crop seed or new equipment. The company is connecting farmers with coaches and peers who can share their experiences with new practices and measuring changes in the ecosystem to gauge how new practices are working. Eventually, they hope to pay farmers based on demonstrable positive outcomes compared with their initial baseline through the non-profit Ecosystem Service Market Consortium (ESMC). They’re making their first payments to farmers in Kansas later this year.

“For farmers, often their biggest cost is trying something new and failing. If you’re experimenting with a new practice, you only get one shot per year, and experimentation is really slow without any extra support,” Rosenzweig says.

Agricultural emissions are 60% of the company’s emission footprint, Rosenzweig says. By targeting those emissions and paying farmers to make the changes that reduce them, the company can meet their sustainability goals.

General Mills’ pilot of the market developed by ESMC is one prominent example of an “inset” program for reducing emissions. This inset program operates on a concept that has been around for a couple decades but is in the midst of a renaissance: carbon markets.

New Kids on the Block

Unlike General Mills, some sectors (airlines and technology) have no direct ties to agriculture. For companies that can’t easily or feasibly reduce their own emissions, paying to “offset” their carbon footprint through carbon markets might be their next best bet.

Here, things get even more complicated. Though programs like General Mills’ pilot relies on carbon credits (using ESMC’s market), the company is purchasing these credits from within its own supply chain. Without direct ties to farmers, companies need a way to make connections that allow them to pay for sustainable practices like carbon sequestration. Enter “offset” carbon markets.

“We’re in the ‘Wild West’ of carbon markets right now,” Iowa State agricultural economist Chad Hart says. “There’s a bunch of companies out here, all trying to set up their own way of doing it, hoping that their way becomes the standard.”

There’s about as many ways to structure carbon markets as there are companies and nonprofits brokering them. A recently released breakdown of the carbon market landscape (see https://bit.ly/2X6UvqJ) goes into a great deal of detail about the technical terminology.Two broad categories of carbon markets currently exist: those based on processes, and those based on outcomes. For producers, this fundamental setup determines how they’ll run their operations to comply with the contract. Process-based programs incentivize farmers to adopt new processes under the assumption that these processes will sequester certain amounts of carbon in the soil. On the other hand, outcome-based contracts reward farmers for the change in sequestered carbon over a certain period of time—the outcome of adopting soil health-friendly processes.

For process-based contracts, companies pay farmers for adopting practices we know are related to carbon sequestration, like switching from conventional tillage to no-till or growing cover crops on fields that used to lay fallow for a season. Frequently, the contracts that farmers sign commit them to maintaining these practices for a certain period. At the end of this designated time, the company offers a payment.

But there are a few sticking points. These types of programs can leave out innovative farmers who have already adopted conservation practices on their own dime. Plus, process-based contracts (usually) operate on an assumption of how much carbon will be sequestered when a producer adopts a new practice.

“That’s where this term ‘additionality’ comes in,” Hart says. “It means we’re looking for changes starting from now, looking forward. We’re not looking back. The argument is that changes made in the past are now baked into the baseline.”

All right, so you create a carbon market that rewards producers for making the switch, but how do you sell those offsets?

For companies using this process-driven approach, they might say, based on previous findings or on models, that switching from conventional tillage to no-till sequesters a ton of carbon per acre, the equivalent of one ton of CO2 removed from the atmosphere. Following that logic, they might say that a producer who made the switch has, over their 10-year contract, sequestered 10 tonnes of carbon from the atmosphere, and so sells a third-party buyer the equivalent amount of carbon credits. Those carbon credits rely on the assumption that 10 tonnes of carbon have been removed from the atmosphere, offsetting that company’s emissions by that amount.

“But what happens in 5 or 10 years when the science evolves, and we figure out that switching from conventional to no-till only saves a quarter tonne per acre per year?” Hart asks. “As the science evolves, what does that mean for payments?”

It’s a sticky question, and there isn’t a perfect solution. So far, companies selling carbon credits typically include a verification process sometime during the contract period. Carbon verification relies on a third-party organization that evaluates the greenhouse gas emissions (or sequestration) on agricultural land.

Hart mentions that one tough part about verification is that someone has to pay that third-party organization. And verification can be expensive.

Here’s where we run up against another problem. What happens if a producer changes their management practices at the end of a contract? After all, it’s way easier to release carbon than it is to store it—just as it’s infinitely easier to compact soil on one rainy planting day than it is to restore it. Plus, for programs that don’t have transparent verification, there’s concern that producers could list the same field in multiple markets, essentially selling carbon that hasn’t been sequestered.

There is a different kind of market working to address many of these questions, and this one is based on outcomes.

Credits Based on Outcomes

The second sort of market relies on outcomes.

In an outcomes-based contract, the producer is paid for carbon that has already been sequestered. The idea, then, is that we avoid the issues introduced by process-based markets by making sure the carbon has already been sequestered.

To give you a better idea, let’s look at one company: Nori (www.nori.com).

Nori is “carbon agnostic,” Agriculture Supply Lead Rebekah Carlson says. “We’re starting with soil, but the idea is that we set up a carbon market that doesn’t fail, whether it’s blue carbon, kelp, or direct air capture.”

Nori’s process relies on total transparency, and it looks something like this. First, the interested producer works with Nori to get their existing farm system data into Nori’s platform. Using this farm system data (including management practices, planting times, yields, nutrient application, and so on), Nori estimates the value of their project before they enroll in the marketplace or invest any money into the process. Nori can look at their projects from the year 2000 onward, using a combination of the farmer’s data and satellite imagery to backfill any missing information.

“Basically, once this whole slew of information is in, the producer can run the model and see what their project is worth,” Carlson says. An NRT, or “Nori Removal Tonne,” is Nori’s carbon credit unit, equivalent to one tonne of carbon removed from the atmosphere and retained in the soil for a minimum of 10 years.

At this point, a farmer has a pretty good idea how much their previous work is worth in terms of NRTs. If their projected NRTs are worth enough, they can go on to the next step of verification, in which a third-party certified body audits the producer to make sure that they did, indeed, adopt regenerative practices at that time.

According to Carlson, verification typically costs US$3,000–$5,000, and that cost is covered by the farmer.

“We want to make sure farmers know what their project is worth before that verification step,” Carlson explains. “We don’t want them to come out negative—this is supposed to be a value asset.”

If a farmer completes the verification process through a certified party (in this case, Aster Global), and receives their verified NRTs, then they sign a 10-year contract to maintain these regenerative practices and keep that sequestered carbon in the soil.

“This is a big talking point, because the value of a carbon credit for a buyer comes from permanence,” Carlson says. “Buyers want to know that the carbon will stay in the ground.”

Finally, Nori uses blockchain as a public ledger to certify that the credits aren’t double-counted. Nori also uses a first-in first-out model, so farmers whose fields were verified first sell their NRTs first, moving down the line. Though this can mean that a farmer might wait several months after verification to get a payment, it allows buyers to see who they’re buying from. Nori just creates the marketplace to link the buyer and the seller.

“Changing your agricultural practice is hard, and we’re trying to give assurance to farmers that using regenerative practices is valuable,” Carlson says. “It’s not just good for your soil health, but good for your pocketbook.”

Closing the Loop: Regulation

The Biden Administration and private entities alike are interested in finding ways to cut back on carbon emissions and draw down carbon out of the atmosphere. Agriculture is an area getting a lot of attention for its potential to sequester atmospheric carbon in the soil, and though the best scientific methods for quantifying soil health at scale aren’t settled, there are ways the government can help.

Though regulation and mandates aren’t always the answer for encouraging adoption of regenerative agriculture practices, there are some aspects of soil health that might benefit from government oversight. It’s closing the loop, bringing the government back into the game to help improve soil health and meet sustainability goals in an open market.

“The federal government could help us create a standardized market,” Hart says. “We need a definition for what a carbon credit actually is, and it pretty much has to come from the government because they’re going to have to enforce that standard. We need trust in that standard in order for the market to survive.”

For now, some farmers innovate without the kickbacks of carbon credits or conservation programs. But to make the widespread, systemic changes the Biden Administration seeks, we need to understand what drives a producer to make a change.

“We’ve found a lot of our innovators, our early adopters, they’re not doing this for the outside incentives,” Bagnall says. “The people who have taught us what we know about soil health practices, they got into it because they believe it’s the right thing to do and they find that it is more profitable.”

For now, monetary incentives through various programs can help interested parties get involved in regenerative agriculture. They’re a stepping-stone for folks who want to do more for their soil health, but they’re not necessarily the reason farmers take on more risk, more change, and more complex systems.

We’re at a tipping point for regenerative agriculture, and with support from these relationships with nonprofits, government programs, and new markets, farmers have more opportunities than ever to dip their toes in the water and make new changes that benefit their soils and society.

Dig Deeper

Read about farmer surveys and soil health in a new Agronomy Journal article, “Soil Health Considerations for Global Food Security,” here: https://doi.org/10.1002/agj2.20783. Also, a recently released breakdown of the carbon market landscape can be found here: https://bit.ly/2X6UvqJ.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.