Gold mines and gardenroots

How co-created citizen science turns research into action

- Co-created citizen science brings scientists and the general public together to pose hypotheses and design and implement research questions, putting findings into action for the people it impacts.

- At the 2020 ASA, CSSA, and SSSA Virtual Annual Meeting, Mónica Ramírez-Andreotta presented her University of Arizona project, Gardenroots, as part of the symposium “Translating Soil Chemistry Science to Improve Human Health.”

- Here, a collaboration between Gardenroots, Sierra Streams Institute, and researchers at the University of California–San Francisco stands as a shining example of the direct impact research can make when it engages the questions the community really wants to see answered.

From sampling soil in preschool gardens to harvesting rainwater near Superfund sites, Mónica Ramírez-Andreotta’s work shows the breadth and impact of partnerships between scientists and community members. Not only does she co-create research questions with the community, but she also engages community scientists in most aspects of the research process. She helps them sample on-site to collect data, assessing environmental risks and providing clear, translated feedback grounded in rigorous science.

For Ramírez-Andreotta, an associate professor at the University of Arizona, answering the questions that impact real communities is the driving force in her research, evident in her presentation at the 2020 Virtual Annual Meeting of ASA, CSSA, and SSSA, titled “Soil Health and Justice” (view here: https://bit.ly/3dtJyEW).

Here, we’ll take a look at how one community’s curiosity about their county’s elevated breast cancer rate led to a series of three studies analyzing arsenic and heavy metal(loid) content from legacy gold mining in soil, dust, water, and vegetables. The community has spurred a body of research that will help decrease its exposure to environmental risk factors with practical approaches. For researchers interested in seeing their science turned into action, co-created citizen science offers a new means of developing rigorous, impactful studies.

Breast Cancer in Nevada County

Nevada County’s breast cancer rate is the third highest in California while next-door neighbors to the south in Placer County experienced the second highest. They clocked in at 138 and 142 cases per 100,000 population, respectively, according to data collected between 2006 and 2015 by the California Cancer Registry. By comparison, the state average incidence in California for the same time period was 122 cases per 100,000 people.

With such high breast cancer rates, it’s no wonder citizens in Nevada County were concerned. A group of people reached out to Sierra Streams Institute (SSI), a local nonprofit organization started 20 years ago to protect the health of the streams and ecosystems of the western Sierra Nevada Mountains. The elevated breast cancer levels might have an environmental link—humans are, after all, part of the ecosystem. So, SSI reached out to the California Breast Cancer Research Program (CBCRP) for help, and CBCRP connected them with Peggy Reynolds, a cancer epidemiologist at the University of California–San Francisco.

“Traditionally breast cancer rates tend to be higher in urban rather than rural areas,” Reynolds says. “Nevada County is quite rural—it’s a bit of an anomaly.”

Reynolds and SSI started digging around for a connection. In urban areas, elevated breast cancer rates are thought to be linked to greater exposure to endocrine disruptors; that is, chemicals capable of mimicking typical hormones present in the body, causing unregulated responses. For example, “xenoestrogens” are natural or synthetic compounds that mimic estrogen’s effects in the body. Common chemical compounds like bisphenol A (BPA) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) act as these kinds of carcinogens.

But for lovely rural Nevada County, what could be mimicking estrogen?

A Gold Mine’s Legacy

J.D. Borthwick, an author, artist, and notorious gambler, wandered through Nevada City, CA in 1850. It was the heyday of the Gold Rush in the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountain range.

“…like all mining towns, [it is] a mixture of staring white frame-houses, dingy old canvass [sic] booths, and log-cabins,” Borthwick wrote of the modest city on the first day of his arrival. “It is beautifully situated on the hills bordering a small creek…The bed of the creek, which had once flowed past the town, was now choked up with heaps of ‘trailings’—the washed dirt from which the gold has been extracted—the white colour of the dirt rendering it still more unsightly.”

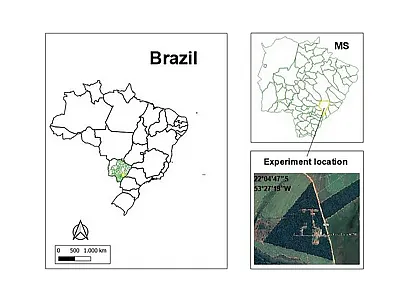

More than 170 years later, the remnants of the Gold Rush remain in the nine counties spanning California’s Gold Country, including the watersheds and soils surrounding scenic Nevada City. Legacy mining operations often left trailings (more commonly referred to as “tailings”) uncovered, free to move as dust particles or through waterways like Borthwick described.

“These legacy tailings are high in arsenic or lead, which goes along with the soil you’d find gold in,” Robert Root, a soil scientist at the University of Arizona, says. “When they’re left exposed, the tailings and metal weather, forming these high-surface-area particles that can be blown around as dust, and abandoned mines aren’t doing dust control like an active mine would.”

Importantly, weathered arsenic and cadmium act as metalloestrogens. In their organic state, as they might be found in undisturbed soil, heavy metals are often bound with large organic molecules. If ingested, the large organic molecules prevent the comparatively small heavy metals from interacting directly with the body. But weathered, inorganic metals, like those in mine tailings, act a little differently. Like BPA or PCBs, ingested inorganic arsenic or cadmium can bind to estrogen receptors. Over time, exposure to arsenic and cadmium can trigger cascades or responses that eventually increase one’s risk of cancer.

After their initial research, the team had their first question. Do women in Nevada County show elevated levels of arsenic and cadmium in their bodies?

Question in hand, the team was funded by CBCRP and named their study: Community Health Impacts of Mining Exposure (CHIME). In CHIME 1, the team collected urine samples and questionnaire results from 60 women over the age of 18 with about half under 35 years old. They found that arsenic levels were, across the sample, elevated compared with the national average body burden and that cadmium levels were elevated in women who had lived in the area for 10 years or more. They published their findings in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health in 2019 (https://bit.ly/3A5mhCJ).

The pilot’s results were a steppingstone for the community. They asked more questions, curious about the impacts of the heavy metals on the most vulnerable segment of the population: children. In most cases, the same amount of heavy metal exposure that has little impact on an adult could be much more severe for a child. Kids, with their expansive cellular division and rapid growth, could experience developmental impacts, behavioral disorders, respiratory problems, and increased risk of cardiovascular diseases and cancer as a result of exposure.

So, what’s going on in the soils that kids commonly interact with at preschool gardens and play areas?

To find out, SSI called upon a program with a great deal of experience testing soils, dust, and water for contaminants. That group is Ramírez-Andreotta’s University of Arizona project, Gardenroots.

Gardenroots

“When I just started my Ph.D., I was sitting in a meeting in August 2008, and I remember community members asking, ‘Are my soils safe? Can I grow food? If so, how much can I eat?’ Those are fundamental and important questions,” Ramírez-Andreotta says. She approached community members, telling them that she didn’t have specific information, but that she wanted to help.

“It took a couple of years, but I ended up getting funding to support my Ph.D., and I got a grant from the [US] EPA Office of Research and Development to do this project in one community, one small town,” Ramírez-Andreotta explains. This was the beginning of Gardenroots.

“We co-create questions, co-collect data, co-design materials, co-communicate with others—that’s the spirit of this whole thing,” Ramírez-Andreotta says.

Now, the program has helped nine different communities dive into “citizen science” research that directly impacts their towns, including the second pilot study conducted in Nevada County. In citizen science research, community members without formal scientific training are active participants in the research process. In co-created citizen science, they work together with scientists every step of the way.

Broadly, this type of community-involved research sees community members documenting and reporting their observations, participating in an environmental monitoring and sampling protocol training, collecting samples from areas they identify as critical, informing data-sharing processes, and receiving their site-specific data from the scientists who conducted the analysis. Finally, the community comes together with the scientists involved to discuss the findings and plot next steps.

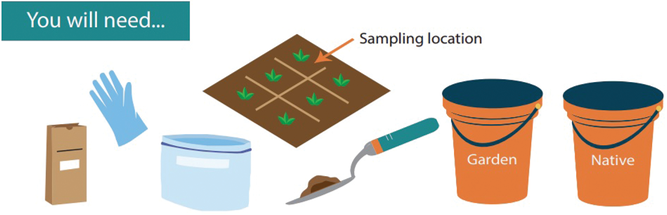

With Gardenroots, Ramírez-Andreotta and University of Arizona master’s student Iliana Manjón helped SSI devise specific questions and created easy-to-follow protocols to help community members take samples in preschool gardens and frequent play areas. They sent out pre-made sampling kits, with specially created sampling guidebooks in both English and Spanish, and trained participants to collect soil, dust, water, and vegetables from the preschool gardens.

Here, the team looked at cadmium, arsenic, and lead. Unlike cadmium and arsenic ingestion, which increase one’s risk of cancer, lead has a different effect altogether. Lead inhalation or ingestion is particularly detrimental to children. The state of California has child-specific health guidance related to lead ingestion because its neurological and developmental impacts are markedly different in children compared with adults. California estimates that an increase of blood lead of just 1 μg/dL can decrease a child’s IQ by one point. Plus, children absorb 40% of the lead they ingest through their intestinal tracts while an adult only absorbs 5–15% of ingested lead.

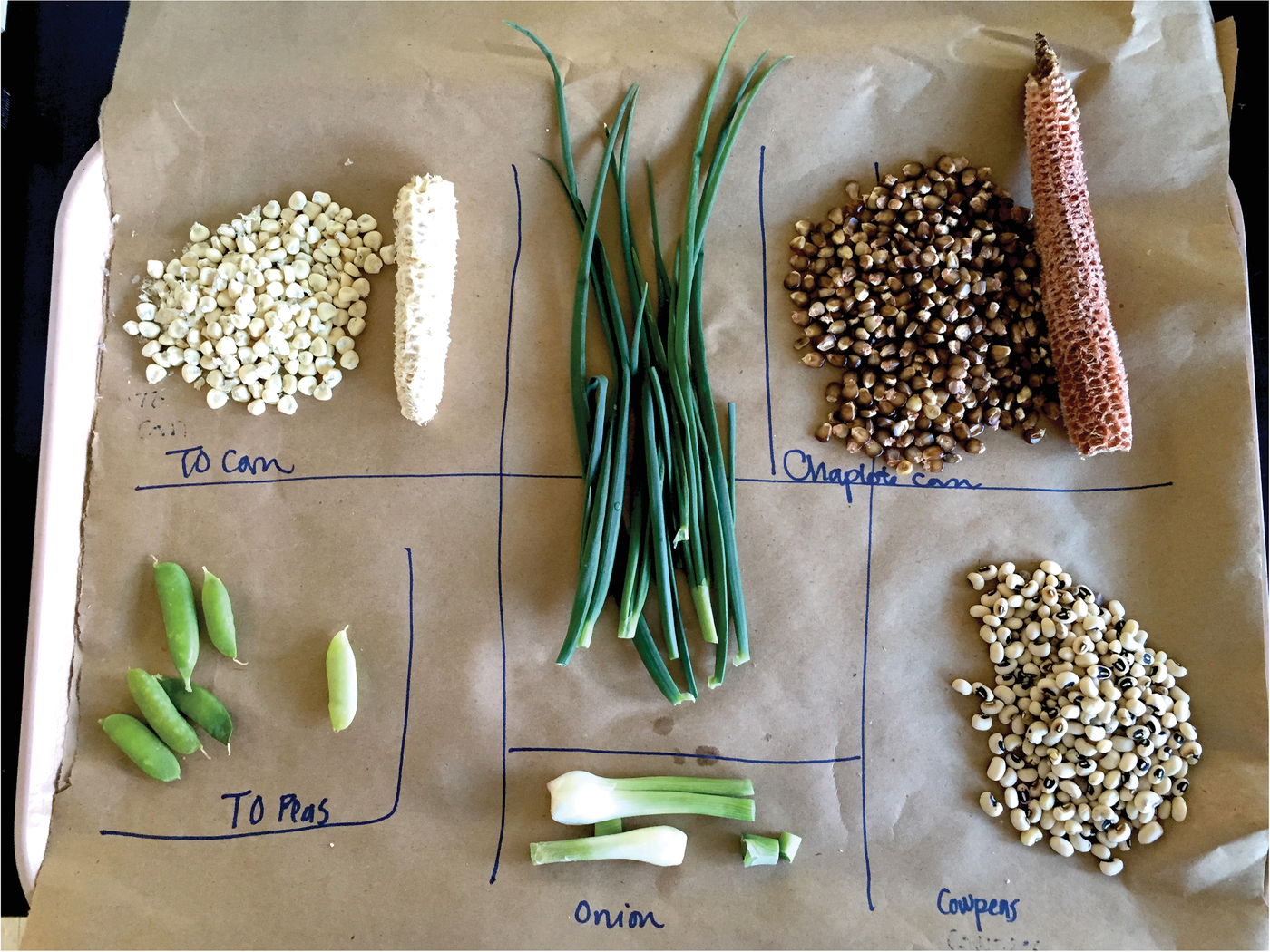

For the gardening component, preschool gardens were asked to grow three different types of veggies to compare uptake. The team made sure to include vegetables the community was already interested in growing.

“It’s something you wouldn’t think about, if you weren’t there talking to people, but what’s the point of measuring uptake in a vegetable they’re not going to grow anyway?” asks ASA and SSSA member Ganga Hettiarachchi. Hettiarachchi organized the symposium at which Ramírez-Andreotta spoke, titled “Translating Soil Chemistry Science to Improve Human Health.” Hettiarachchi has completed numerous community-based research studies while at Kansas State University. Notably, she’s helped test soils and remediate community gardens on brownfields, which are underutilized, mildly contaminated soils.

In Nevada County, Gardenroots helped SSI staff and citizen scientists collect carrot, lettuce, cabbage or kale, and mint or cilantro from each site. Each vegetable has different characteristics and can accumulate metals differently, so testing them across sites is important.

Besides vegetable samples, Gardenroots and SSI also asked participants to take soil, water, and dust samples from each of the four preschools in the study. All samples were sent back to Ramírez-Andreotta’s Integrated Environmental Science and Health Risk Laboratory at the University of Arizona for preparation and analyses.

For soil samples, 5-gal-worth of surface soil was collected from community-identified garden and playground areas. Then Ramírez-Andreotta and Manjón looped in scientists A. Eduardo Sáez and Robert Root. The researchers used a specially built machine that creates fine particle-sized dust from bulk soil samples.

“It’s this great apparatus that helps us produce a large quantity of particulate matter that’s the same size as the dust you’d encounter in the environment,” Root says. Along with dust samples from the study areas, the team also used bulk soil samples from the gardens, batting them around a 40-gal drum with paddles in it. The machine looks kind of like a clothes dryer with a particle separator that removes all dust that’s 10 microns or smaller.

This seems like an awful lot of effort just for some dust, but the team found that the concentration of heavy metal particles in a dust sample is quite different from concentrations you might find by ball milling a collected field sample.

“There’s lots of quartz and feldspar in there that we’d crush up, but what we’re really looking for are the fine, high-surface-area, highly reactive particles that are present in small quantities in a bulk soil sample,” Root explains. Those highly reactive, high-surface-area particles are more likely to be found in greater concentrations in dust.

It’s an important distinction. With more accurate representations of heavy metal concentrations in both dust and soil samples, the team can better understand the potential human exposures in the area.

Plus, Gardenroots and SSI collected information from parents about how often children eat vegetables grown in the garden, their child’s behavior, gardening activities, and how much time they spend outside in the garden areas.

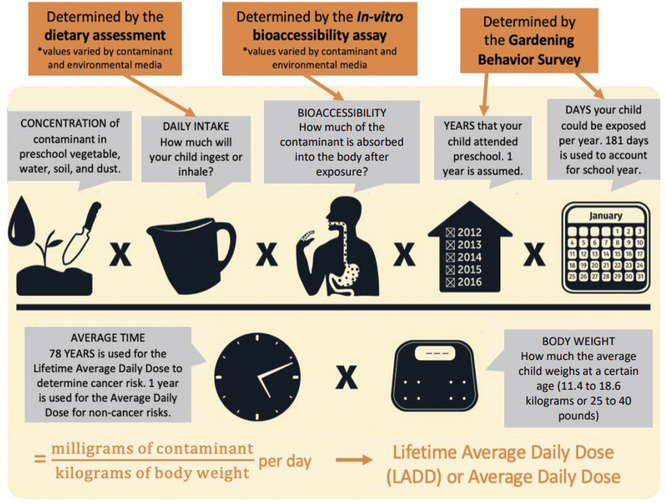

Soil and dust samples were then analyzed by in vitro bioaccessability assays (IVBA) using synthetic lung and gastric fluids. The IVBA results estimate the bioaccessible fraction of arsenic, cadmium, and lead in the body, showing how much would be available to target human organs.

A Preschool Garden Risk Assessment

Based on all this data, Manjón and Ramírez-Andreotta conducted a comprehensive exposure assessment, characterizing the potential lifetime risks posed by the pathways of exposure children might experience.

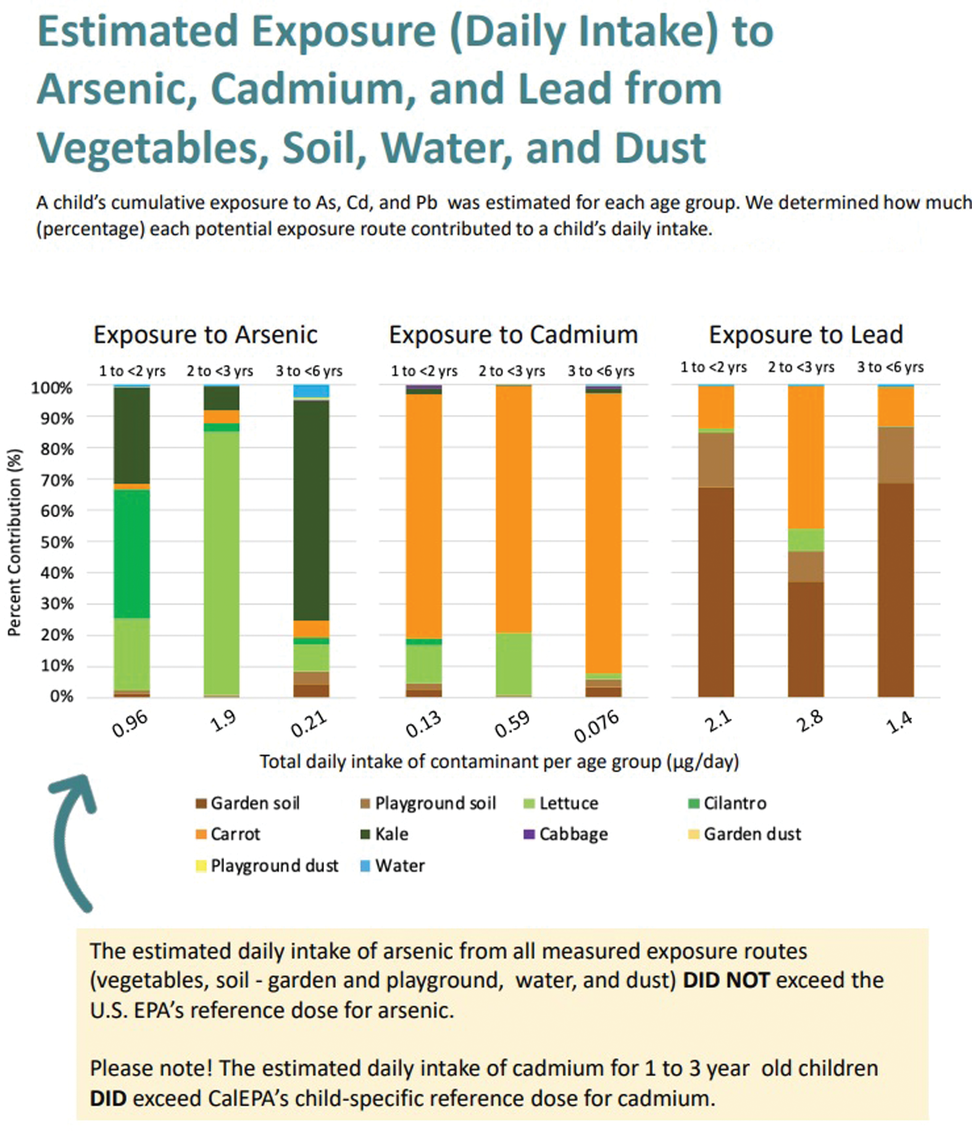

Results of the exposure assessment and risk characterization revealed that children between one to less than three years old may be exposed to levels of cadmium that exceed the California EPA’s recommendations.

As for the vegetables, the team compared arsenic, lead, and cadmium concentrations in preschool-grown veggies to store-bought samples. They found that preschool-grown carrots were higher in concentrations of all three metalloids while lettuce accumulated more arsenic and lead and cabbage accumulated more arsenic and cadmium. Cilantro and kale accumulated arsenic at higher levels, as well.

Grassroots and SSI recommended that community members carefully wash vegetables grown in their gardens, using a scrub brush to remove any soil particles from the veggie’s surface. To be prudent, they suggested mixing up the source of your vegetables, perhaps by incorporating more from the supermarket. To be extra prudent, they recommended limiting consumption of locally grown vegetables that accumulated the most metalloids, like carrot and kale.

The team found elevated levels of lead in some garden and playground soils, but very little lead moved into the plants themselves. Because lead ingestion poses the potential for irreversible neurological damage, the team recommended that the school limit children’s access to these sites until the soil is remediated.

It’s one thing to write to fellow scientists about exposure to carcinogenic contaminants, but it’s another thing entirely to present this information to the study participants, community members, and schools who are actually living in contaminated areas. It’s a tricky business, but Ramírez-Andreotta is a seasoned professional and skilled science communicator. Gardenroots follows a “community-first communication model.” In this model, the investigator releases the results promptly, giving individual participants their results first and then contextualizing communication efforts to minimize pointless concern. Plus, Gardenroots hosts community gatherings and data-sharing events to foster conversation and ensure participants understand the results.

Ramírez-Andreotta works closely with her collaborators, presenting the data to participants and stakeholders ahead of broader community gatherings to make sure they can understand it and asking about what works and what doesn’t. In Nevada County’s case, the community advisory board that was helping SSI guide the study served as the first “test” of the research presentation.

By the time information is released on the Gardenroots website, it’s been through multiple iterations. Ramírez-Andreotta’s lab at the University of Arizona writes up the results, gets feedback from end users and other stakeholders, then revises the information as necessary.

“Iterative beta-testing and formative evaluation leads to successful science communication,” she says.

Next Steps

Now, SSI is continuing its collaboration with Gardenroots and Reynolds (along with the CBCRP and University of California–San Francisco) to complete CHIME 3, a third exposure study designed to look at home gardens and yard soil, dust, and irrigation water to see exposure for people in nine California counties with legacy gold mines. Although CHIME 3 started just as the pandemic picked up, which set back some of their plans for participation and sampling, Taylor Schobel, the project lead, is hopeful about the results.

“We’re really hoping to look at the exposure routes people face at home to get a sense of their household risk factors,” Schobel says. “The best part of all this is at the end, we can give people really practical advice for ways to decrease their exposure. It’s often as simple as wearing specific clothes you keep just for hiking or gardening and washing them as soon as they get dusty or dirty, keeping soil out of the house. Or it could be growing food in raised beds instead of in native soil; or making sure you take off your shoes when you come in the house. Those little things can make a big difference.”

It’s a recurring theme, but over and over again, researchers emphasize that the way to make meaningful, impactful change is to work across disciplines with multiple stakeholders. For Gardenroots and SSI, developing research questions in tandem with the community is a great way to engage community stakeholders. Finally, it’s not just about creating rigorous scientific work as a scaffold for a deeper understanding of our environment, but about getting that information out accurately, in a way that encourages change.

For Ramírez-Andreotta, Hettiarachchi, Schobel, Reynolds, Root, and all the other researchers involved in some form of community-engaged research, that means getting “boots on the ground.” It means going to places where people actually spend time—like parks, community gardens, libraries, schools—and really listening.

“That’s the key to all this. You meet people where they are and you listen,” Ramírez-Andreotta says. “You have to have cultural humility—it’s not about you. But when you do community-engaged translational science, the chances of seeing your research turn into action increase.”

DIG DEEPER

- You can find Ramírez-Andreotta’s presentation at the 2020 Annual Meeting, “Soil Health and Justice” here: https://bit.ly/3dtJyEW

- The symposium containing related research presented at the 2020 Annual Meeting, “Translating Soil Chemistry Science to Improve Human Health,” can be found here: https://bit.ly/3qxq9rM

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.