The world’s first diploid recombinant inbred potato population

- The tetraploid potato is tremendously tricky to breed—it has four sets of 12 chromosomes and 40 agronomic traits that are necessary for commercial production.

- The diploid potato offers an answer for quicker, more reliable breeding, but it’s widely self-incompatible.

- Here, breeders at Michigan State University detail in Crop Science the first ever diploid recombinant inbred line population of potato, complete with Colorado potato beetle resistance, for use in breeding operations and genetic mapping.

Being a potato breeder is kind of like playing the world’s most complex game of 48-die Yahtzee. Your typical russet or red has four copies of its 12 chromosomes, and it’s notoriously difficult to get new traits to show up where you want them—and to keep them there.

“Every trait you consider important segregates in every cross you make—you’re always creating something, then mixing it up every time you cross it,” says David Douches, a potato breeder at Michigan State University (MSU). “Whereas, in self-pollinating crops, you introduce a trait, get it into a background, so it doesn’t segregate anymore, then build off it.”

Potato breeders have long sought an alternative to cumbersome tetraploid breeding by looking to diploid potatoes, including many of the crop wild relatives of commercial varieties. With only two sets of 12 chromosomes, breeders hope to create inbred potato lines, just like corn or wheat, that contain the 40 or so beneficial agronomic traits that producers and markets desire, as well as a high level of homozygosity. That is, researchers want to see most, if not all, alleles are the same on both copies of each chromosome. Then breeders could introduce a new trait or study inbred lines with assurance that they’re not changing too many other agronomically desirable traits.

There’s just one little snag.

“Diploid potatoes really, really do not like to self-pollinate,” says Shelley Jansky, a professor emeritus at University of Wisconsin–Madison and retired USDA-ARS research geneticist. Most species of diploid potato—including the oft-used Solanum chacoense—will not create viable seed if they are pollinated by their own plant’s pollen. This means that most diploids don’t produce inbred true seed.

Luckily, enterprising researchers in the Douches Lab at MSU made incredible breakthroughs in breeding an inbred line of diploid potato. A new article in Crop Science (https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.20534) details a new breeding line population, inbred for five generations, which is a tremendous step forward in both introducing pest and disease resistance and shaking up traditional potato production.

Before we can dive in as first author Natalie Kaiser and principal investigator Douches talk about this breakthrough line, we need to chat about a mystery.

The Mysterious M6

When Shelley Jansky took her position as a research geneticist back in 2004, she inherited a whole lot of genetic material, including a monstrous number of envelopes filled with potato seed.

“There was this collection of seed packets, probably 30 or 40 of them, and they all said S7 on them,” Jansky remembers. “Unfortunately, I didn’t have Bob [Hanneman] there to tell me what everything was, but I assumed that the ‘S’ meant it was the seventh generation of selfing [self-pollinating].”

Hanneman, the prior joint-appointed research geneticist for the USDA-ARS and University of Wisconsin, passed away suddenly in 2003, leaving his substantial body of work on diploid potato behind. In fact, Hanneman and his collaborator Kazuyoshi Hosaka detailed the allele responsible for transmission of self-compatibility to the next generation of diploid potato. They traced it to the S-locus inhibitor (Sli) on chromosome 12 in work published in Euphytica in 1998 (https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018353613431). It was this legacy that tipped Jansky off about the potential identity of the S7-labelled seeds.

So Jansky followed her hunch and planted the seeds out in the greenhouse. She found seed from one packet was pretty vigorous, and one seedling in particular outgrew the others. She self-pollinated it, saved it, and started a breeding line.

“We thought it would be a good breeding line because of its vigor, fertility, and self-compatibility,” Jansky says. “We called it M6, and we haven’t found anything better—or even as good as it—yet.”

Jansky knows that M6 is from a diploid wild relative of potato, Solanum chacoense. She knows that it’s self-compatible, which means that the plant does not reject fertilization with its own pollen, and that it passes self-compatibility to its offspring consistently. But she doesn’t know which line(s) of Solanum chacoense Hanneman and Hosaka used to generate M6.

Regardless, Jansky and her coauthors, Young Sook Chung and Piya Kittipadakul, registered M6 publicly in the Journal of Plant Registrations in 2013 (https://doi.org/10.3198/jpr2013.05.0024crg).

When members of the Douches Lab were looking for sources of self-fertility in diploid potato, they turned to M6.

A Diploid Inbred Line

If you wanted to produce true seed from a tetraploid potato line, you’d need to inbreed it. You’d take pollen from the plant, fertilize its own ovary, produce seeds, plant them out, hope they grow, and repeat.

“It would take 20 generations of self-pollination for a tetraploid line to reach 99% homozygosity,” Jansky says.

But 20 years is an awfully long time for one line—half of a researcher’s career, realistically. With diploid potato, that timeline could be much, much shorter. It could cut down the time it takes for breeders to create varieties that respond to the needs of both markets and growers, like adding in resistant lines; breeding for a new tuber color, shape, or flavor; or finding more durable, resilient plants that handle ever-changing climatic conditions.

“We’ve known for a long time that it’s incredibly challenging to get the right combination of genes that control all 40 of those traits,” Kaiser says. “But diploid breeding has been a daunting task. It took a number of partners in the U.S. and Europe coming together, saying now is the time to invest the time and resources into understanding how to make a valuable potato product at the diploid level.”

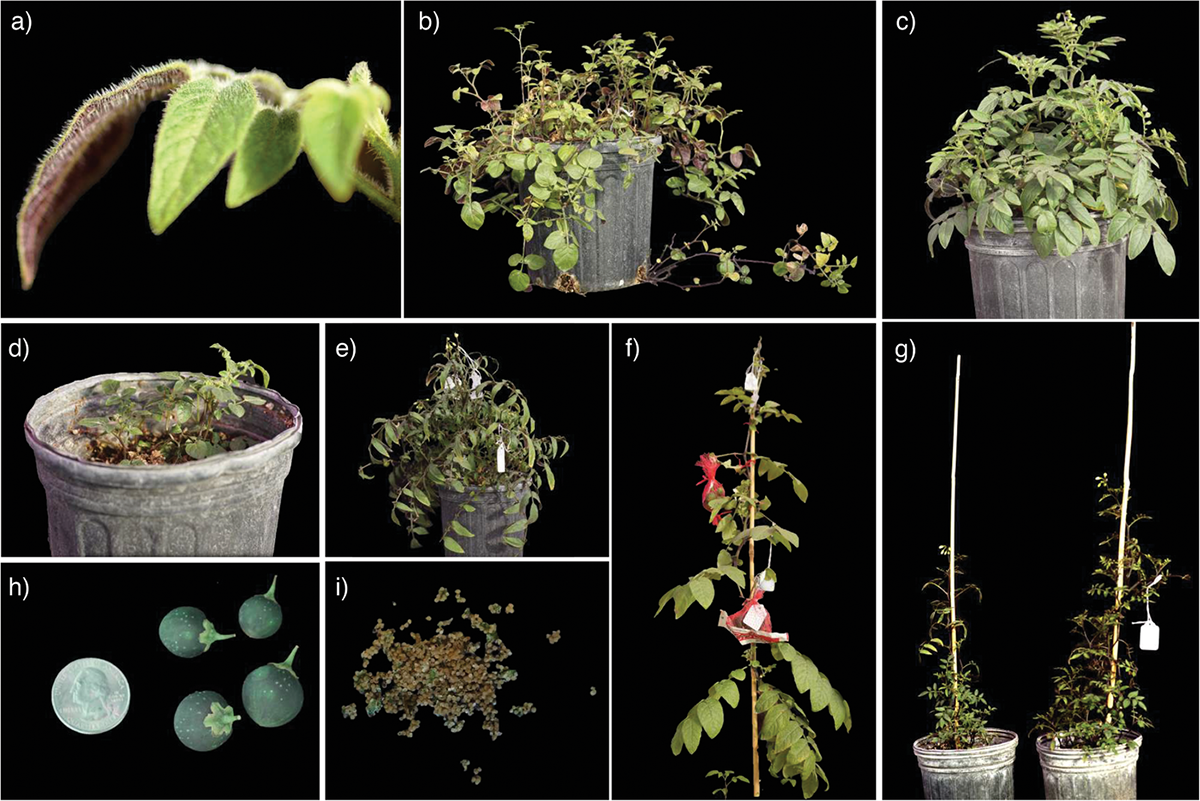

To create a diploid recombinant inbred line (RIL), Kaiser used M6 as the diploid female parent, pollinating it with the S. chacoense clone 80-1 to introduce Colorado potato beetle resistance (which we’ll tackle in a minute). The cross resulted in 20 F1 plants, from which Kaiser selected a single individual with Colorado potato beetle resistance to produce 700 diploid F2 seedlings. The whittling-down continued as Kaiser found only 325 grew and developed. She evaluated these for self-compatibility by hand-pollinating them in the greenhouse to see if their fruit set. This is where Kaiser visualized something incredible.

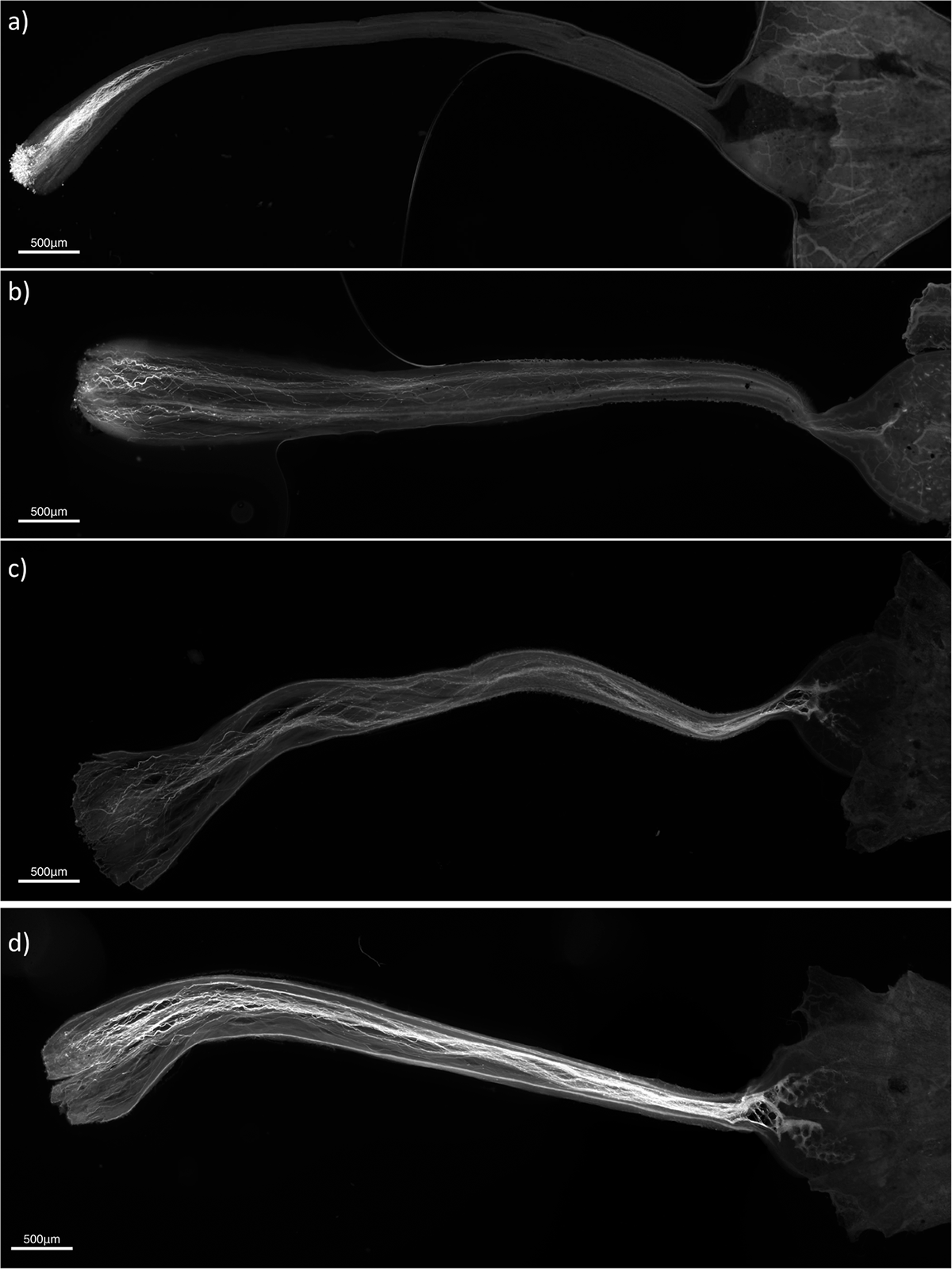

Kaiser looked at the stigma, style, and ovary of self-fertilized F5 potatoes under a microscope, staining the pollen blue to see what was going on in the style itself. Previously, researchers posited that self-incompatibility was likely due to a mechanism in the style, in which the plant shuts down pollen tube growth before it reaches the ovary, preventing it from creating a seed. But Kaiser’s microscopy showed that sometimes pollen tubes reached the ovary, but the potato still didn’t produce seed. There’s something else going on—more than just the Sli allele—that’s keeping potatoes from being self-compatible.

“Natalie [Kaiser] really took the initiative to develop this new phenotyping method using the microscope that we hadn’t done before,” Jansky says. “Before, we would just assume that lines that did not produce seeds after self-pollination were self-incompatible.”

Jansky explains that the lack of seed production in potatoes that researchers self-pollinated could be due to other factors, including poor pollen viability or a suboptimal pollination environment. But Natalie’s microscopic stylar analysis method parses apart those different possibilities, giving researchers better insights into the self-incompatibility process.

After pioneering a new means of phenotyping diploid potato compatibility, Kaiser pressed on with breeding. She advanced the progeny to the F5 generation by growing five plants from each family to make sure at least one was self-compatible. She saved tissue cultures (or clones) from parental lines and the F2, F4, and F5 generations.

“It was so hard, deciding which plants to put in tissue culture,” Kaiser says. “You keep some in case anything happens to your lines—you have it to go back to later. As much as I wanted to keep everything, we just don’t have the greenhouse space or the time, realistically. You always wonder what you’re losing.”

By the time Kaiser was ready to test the lines in the field, she had 98 F4 and 74 F5 individuals, from which she took stem cuttings and propagated them in the greenhouse. Eventually, in the spring of 2019 and 2020, she planted them out in MSU’s test field.

Colorado Potato Beetle Resistance

Kaiser’s breath caught in her throat as she parked beside the potato field in the summers of 2019 and 2020. By the end of the summer, the “beetle-apocalypse” sets in at Michigan State University’s Montcalm Research Center, where scientists have maintained an active, ravenous population of Colorado potato beetles in a field by supplying them with susceptible varieties of potato.

“It’s nerve-wracking,” Kaiser says. “You want to see lots of beetles, because that means there’s lots of pest pressure, but at the same time, you want your lines to be resistant. You still want to see some green in your field.”

The adult Colorado potato beetles emerge from the soil as the weather warms, feeding on the freshly transplanted susceptible potato plants the team grows between rows of research lines. The beetles feast; lay eggs that hatch into larvae that get “bigger, juicier, hungrier”; go down in the soil; and emerge as adults, Kaiser says. This cycle repeats three or four times in a single season before the beetles overwinter again. By July or August, a field of susceptible potatoes is decimated if you don’t apply multiple rounds of pesticide. Another twist: the potato beetle is resistant to most pesticides and has a remarkable capacity for rapidly evolving resistance to new threats; so much so that scientists frequently use it as a model species to study evolution.

But as Kaiser walked the test fields as the growing season carried on, she found some of her lines survived. There were islands of green among the ravaged plants, showing their resistance to the beetles through incorporation of genetics conferring the plants with certain glycoalkaloids called leptines in their leaves. These toxic glycoalkaloids fend off the beetles, and for commercially viable diploid options, researchers will have to make sure the leptines are only produced in the leaves, not the tubers.

But how long could resistant potatoes hold out against the hungry, juicy potato beetle larvae?

“The potato beetle has been incredibly successful in adapting to new chemistries,” says Yolanda Chen, an entomologist at University of Vermont. Chen has been working to understand how the potato beetle overcomes toxin exposure, beating pesticides and plant resistance.

In fact, her lab analyzed the beetles at the molecular level. Chen’s lab posited that the potato beetle evolves resistance in a way that defies the timeline of typical evolution. They overcome too many compounds, too quickly, with too limited a genetic background to be relying entirely on aberrant beneficial mutations in their genomes alone.

Instead, Chen’s lab tested a new theory: that beetles use epigenetic mechanisms, triggered by toxin exposure, to overcome the threat. Her team looked at methylation rates in beetles exposed to toxic compounds, comparing them to beetles who had not been exposed. They found that the beetles they exposed to toxins, no matter in what amount, showed decreased DNA methylation. This change in methylation suggests that there is some kind of epigenetic change in either gene regulation—or suppression of transposable elements—that’s related to the beetle’s exposure to toxins.

Plus, Chen’s lab found that these epigenetic changes appeared in the grandbabies (two generations removed) of toxin-exposed beetles, even when the offspring themselves had never encountered the toxin. It’s a step forward in understanding the rapid evolution of the Colorado potato beetle and how it manages to overcome pesticides so quickly. Their findings were recently published in Evolutionary Applications (https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.13153).

But the potato beetle isn’t going anywhere. Resistant lines coupled with well-managed pesticide use and perhaps beneficial insect pressure could help potato farmers protect our future chips, French fries, and baked potatoes. The integration of resistance in the form of foliar leptine glycoalkaloids by the Douches Lab is just one early example of how diploid potato could help researchers finagle new lines that solve growers’ problems in the field.

In fact, the Douches Lab is currently running tests with these potato beetle-resistant lines in the field to see if the beetles can evolve resistance to leptines like they do with pesticides. The trials will give us a better sense of how long resistance could hold out against the beetles; but for now, we’ll just have to wait and see.

A Triumph

We’ve only skimmed the surface of the hard work the MSU team put into developing this recombinant inbred line of diploid potatoes, but their findings are truly remarkable. The new lines developed by the Douches Lab members will likely serve as a widely used mapping population for diploid potato, just as there are well-documented populations for wheat, corn, soybean, or many other diploid plants.

“Breeders…we’re eternal optimists,” Douches qualifies. “But we have huge potential here to not rely so much on pesticides, to map genetic variation in our potatoes, and to better understand how we can use diploid potato to advance potato breeding.”

Currently, the potato supply chain sees certain growers using seed potatoes, clonally propagated from tissue cuttings, grown up in the greenhouse, and transplanted to the field. There, the potato tubers multiply, and the grower spends three or four seasons increasing the number of seed tubers they have—all genetically identical—before sending them off to producers as certified seed tubers. With such bottlenecked genetics, potatoes are highly susceptible to diseases like potato virus Y, and production requires the transport of heavy, living material in the form of seed tubers.

With true seed, transportation and storage become extraordinarily easy compared with the transportation of seed potatoes. You can send true seed in envelopes, store it somewhere cool and dry, plant it out to grow seedlings in a greenhouse, and then take them out in the field.

“This paper is a triumph. Absolutely, number one, its greatest strength is creating a set of recombinant inbred lines,” Jansky says. And the Crop Science article details the very first RIL of potato ever published. It builds on decades of research in the potato community, gathers the findings and seeds and accumulated knowledge of dozens of researchers in its arms, and releases it to the world, building on decades of research in the potato community and releasing it to the world.

Instead, Chen’s lab tested a new theory: that beetles use epigenetic mechanisms, triggered by toxin exposure, to overcome the threat. Her team looked at methylation rates in beetles exposed to toxic compounds, comparing them to beetles who had not been exposed. They found that the beetles they exposed to toxins, no matter in what amount, showed decreased DNA methylation. This change in methylation suggests that there is some kind of epigenetic change in either gene regulation—or suppression of transposable elements—that’s related to the beetle’s exposure to toxins.

Plus, Chen’s lab found that these epigenetic changes appeared in the grandbabies (two generations removed) of toxin-exposed beetles, even when the offspring themselves had never encountered the toxin. It’s a step forward in understanding the rapid evolution of the Colorado potato beetle and how it manages to overcome pesticides so quickly. Their findings were recently published in Evolutionary Applications (https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.13153).

But the potato beetle isn’t going anywhere. Resistant lines coupled with well-managed pesticide use and perhaps beneficial insect pressure could help potato farmers protect our future chips, French fries, and baked potatoes. The integration of resistance in the form of foliar leptine glycoalkaloids by the Douches Lab is just one early example of how diploid potato could help researchers finagle new lines that solve growers’ problems in the field.

In fact, the Douches Lab is currently running tests with these potato beetle-resistant lines in the field to see if the beetles can evolve resistance to leptines like they do with pesticides. The trials will give us a better sense of how long resistance could hold out against the beetles; but for now, we’ll just have to wait and see.

A Triumph

We’ve only skimmed the surface of the hard work the MSU team put into developing this recombinant inbred line of diploid potatoes, but their findings are truly remarkable. The new lines developed by the Douches Lab members will likely serve as a widely used mapping population for diploid potato, just as there are well-documented populations for wheat, corn, soybean, or many other diploid plants.

“Breeders…we’re eternal optimists,” Douches qualifies. “But we have huge potential here to not rely so much on pesticides, to map genetic variation in our potatoes, and to better understand how we can use diploid potato to advance potato breeding.”

Currently, the potato supply chain sees certain growers using seed potatoes, clonally propagated from tissue cuttings, grown up in the greenhouse, and transplanted to the field. There, the potato tubers multiply, and the grower spends three or four seasons increasing the number of seed tubers they have—all genetically identical—before sending them off to producers as certified seed tubers. With such bottlenecked genetics, potatoes are highly susceptible to diseases like potato virus Y, and production requires the transport of heavy, living material in the form of seed tubers.

With true seed, transportation and storage become extraordinarily easy compared with the transportation of seed potatoes. You can send true seed in envelopes, store it somewhere cool and dry, plant it out to grow seedlings in a greenhouse, and then take them out in the field.

“This paper is a triumph. Absolutely, number one, its greatest strength is creating a set of recombinant inbred lines,” Jansky says. And the Crop Science article details the very first RIL of potato ever published. It builds on decades of research in the potato community, gathers the findings and seeds and accumulated knowledge of dozens of researchers in its arms, and releases it to the world, building on decades of research in the potato community and releasing it to the world.

Dig Deeper

Read the original Crop Science article, “Self-Fertility and Resistance to the Colorado Potato Beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) in a Diploid Solanum chacoense Recombinant Inbred Line Population” here: https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.20534.

Read the release of M6 in the Journal of Plant Registrations, “M6: A Diploid Potato Inbred Line for Use in Breeding and Genetics Research” here: https://doi.org/10.3198/jpr2013.05.0024crg.

- Janak R. Joshi, Dev Paudel, Ethan Eddy, Amy O. Charkowski, Adam L. Heuberger, Plant necrotrophic bacterial disease resistance phenotypes, QTL, and metabolites identified through integrated genetic mapping and metabolomics in Solanum species, Frontiers in Plant Science, 10.3389/fpls.2024.1336513, 15, (2024).

Johanna Blossei, Roman Gäbelein, Thilo Hammann, Ralf Uptmoor, Late blight resistance in wild potato species—Resources for future potato () breeding, Plant Breeding, 10.1111/pbr.13023, 141, 3, (314-331), (2022).

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.