Measuring evapotranspiration in rain gardens with soil moisture sensors

- Rain gardens can reduce stormwater runoff, filter contaminants, offset carbon emissions, and provide food and shelter for wildlife, but evapotranspiration is often overlooked.

- New Vadose Zone Journal research found soil moisture sensors have the potential to estimate evapotranspiration in rain gardens.

- Evapotranspiration volumes should be considered in rain garden design.

Rain gardens are popular on both large and small scales, commercially and residentially, for pure functionality and to add curb appeal. These depressed areas filled with plants can reduce stormwater runoff, filter contaminants, offset carbon emissions, and provide food and shelter for all kinds of wildlife.

Rain gardens are a form of green infrastructure. Compared with gray infrastructure, which consists of pipes and concrete caverns that hold and control stormwater, green infrastructure works to intentionally restore the natural hydrological cycle rather than moving water as quickly as possible.

Researchers at Villanova University have homed in an often-overlooked aspect of rain gardens: evapotranspiration, the process of water leaving the plants and soil via evaporation and transpiration. They point out that it’s important to think beyond the few hours after a rain event when a large amount of water is moving through a rain garden via infiltration and drainage. In the ensuing days and weeks, it’s evapotranspiration—particularly from plants transpiring in the summer—that begins to play a key role in removing water from the rain garden and allowing it to be prepared for the next rain event.

“Infiltration is definitely the driver of immediate removal of water, and it’s something you want the system to do,” says Amanda Hess, a postdoctoral researcher at Villanova and lead author on a recent Vadose Zone Journal study on measuring evapotranspiration in rain gardens. “Because it happens right then and there during a rain event, infiltration is usually the focus. On the other hand, evapotranspiration isn’t always considered a loss mechanism because it’s not happening right away in large quantities. But over the course of a year, there is in fact a lot of it happening. So being able to fully account for the holistic performance of the rain garden is very important.”

Making Evapotranspiration Easier to Measure

The problem Hess and Andrea Welker and Bridget Wadzuk, Villanova civil and environmental engineering professors, wanted to tackle was making evapotranspiration in rain gardens easier to measure. In concept, knowing how much water is lost to evapotranspiration seems beautiful in its simplicity—measure how much water is going in and how much water exits through the bottom of the soil and subtract them because the only other way for water to leave the system is evapotranspiration. However, there are many other variables and complexities at play, and being able to gather high quality data and make good estimations is critical.

The gold standard for knowing how much water is leaving soil is the weighing lysimeter, an incredibly expensive piece of equipment not accessible to most working outside of a research setting. It is a designed system that doesn’t provide much flexibility. There are other tools, as well as complex equations and estimations that use climate data, but the researchers focused on the use of relatively common soil moisture sensors that can be inserted into almost any soil.

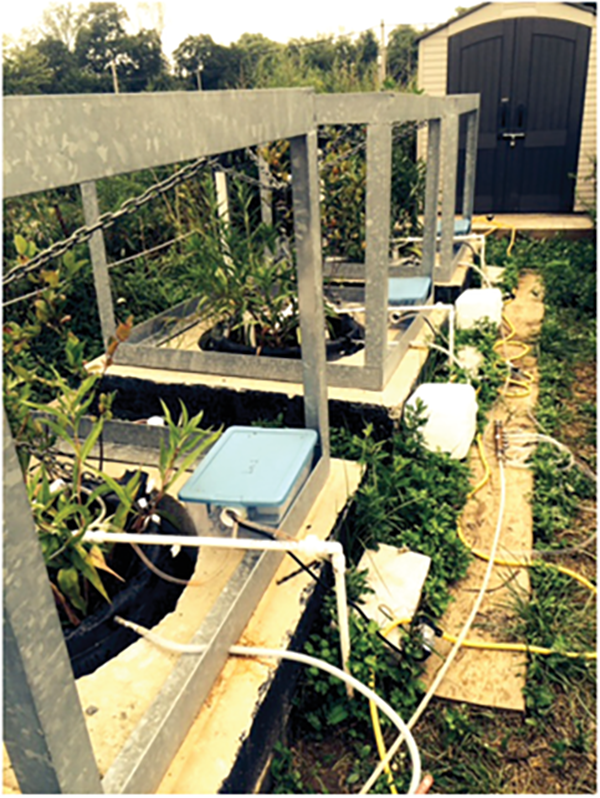

Their study calculated daily evapotranspiration over a three-year period using both lysimeters and soil moisture sensors and then compared the two. They used soil moisture sensors at three different depths in the soil: the top, middle, and bottom. They found the sensors performed relatively well, particularly the one at the bottom, which they say may have been because the soil they studied was relatively homogenous.

“We had the lysimeters as the ‘right answer’ and were able to compare our soil moisture sensor data to that,” Welker explains. “Ideally, we can take the method, soil moisture sensors, and resulting equation and apply it to other places that don’t have weighing lysimeters readily available.”

The researchers hope that by being able to measure evapotranspiration much easier, the proverbial floodgates will open for others. They say managers of a commercial property or staff of a municipal parks department may be interested in proving that rain gardens they are installing are working effectively.

“One of the things I really like about rain gardens is that they are highly scalable,” Welker says. “You can have them on both commercial and residential properties. A homeowner can install one at a fairly low cost. Some are more sophisticated than others, and some folks may be interested in studying the evapotranspiration of theirs, but they are very scalable and going to have a positive impact no matter the scale.”

First Step Towards Climate-Specific Optimization

Knowing how to easily measure evapotranspiration is the first step to further studying and understanding how to optimize a rain garden for a specific climate, the researchers note. They know that more surface area and more plants promote evapotranspiration. Survivability of the plants is also key. For example, lots of salts in stormwater or plants that cannot tolerate soil that stays wet for long periods can cause problems. They also know that design elements like an upturned elbow may increase evapotranspiration.

“It’s a big ask right now because people designing rain gardens want to know about evapotranspiration,” Hess says. “We want to bring evapotranspiration, as well as monitoring, more prevalently into design, especially to gather site-specific information. Knowing that a rain garden can sustain itself and be ready for the next rain event is critical. We believe that rain gardens are a great tool in the toolbox in terms of stormwater solutions.”

Hess and Welker also recognize the limits of rain gardens and draw an important distinction between stormwater and floodwater. The goal of rain gardens is to capture stormwater runoff and remove and filter it in a more natural way, rather than defend an area against rising flood waters. Elements of gray infrastructure for dealing with rare influxes of floodwaters will still be needed, they say.

Their next steps in this work will be to use soil moisture sensors to study further designs of rain gardens, such as using an upturned elbow to keep more water in the garden for use by plants. Many scientists have questions about how this can affect evapotranspiration, and their new method allows them to measure it easier than before.

“Being able to fully explain the performance of rain gardens will begin to answer a lot of research and useability questions,” Hess says. “We will keep learning more through continued simulation to see how rain gardens respond to different kinds of events and also climate change. That’s where we are headed.”

Dig Deeper

Read the original article, “Evapotranspiration Estimation in Rain Gardens Using Soil Moisture Sensors,” in Vadose Zone Journal at https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20100.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.