Sustainable agriculture in the U.S. vs. the EU

There is common ground between the United States (U.S.) and the European Union (EU) on many aspects of sustainable agriculture. Indeed, the world is largely aligned on the agricultural goal to produce safe, abundant, and affordable food to support a growing global population without loss of the earth’s production capability over time. There is global consensus that achieving “sustainability” requires economic, social, and environmental components as essential and interdependent success factors. However, the world differs widely on the best ways to achieve these goals. Two of the largest agricultural regions, the U.S. and the EU, for example, have mostly antithetical philosophies and approaches to achieve the outcomes. This polarization on how to achieve sustainable agriculture, which is the basis for this article, diminishes the role of science as the arbiter for advancing sustainable agriculture, risks the harmonization for global trade among all nations, and threatens agrarian nations already facing severe food insecurity.

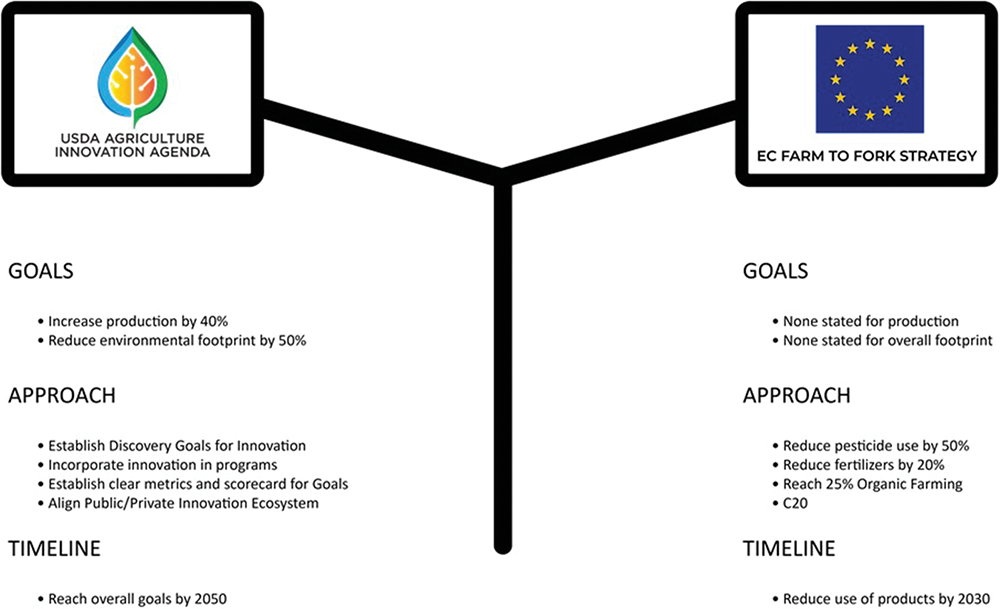

The differences are seemingly complex, but essentially have one key difference: the United States has focused on outcomes and asserts that science, translated through technology and product innovation, is the solution to the complex objectives of both production and production capability, whereas many in the EU have focused on inputs and believe that “less is more” regarding technology and that natural systems are sufficient to achieve production, preserve nature, and sustain the environment. These differences are clearly recognized in recent actions from both governments. The USDA has initiated the Agriculture Innovation Agenda with an overarching goal to increase production by 40% through productivity improvements while simultaneously reducing the U.S. agricultural footprint by 50%. Technology and agronomic innovation, both incremental and transformative, is at the core of this policy by the U.S., and it seeks to strengthen the relationships and resolve of both the public- and private-sector innovators to meet the challenge. This paradigm shift focuses on “improving” vs. “removing” the tools, techniques, and technologies to address the environmental footprint goal as well as the production goal.

By contrast, the European Commission (EC) recently published its Farm to Fork Strategy with stated goals to reduce the use of most existing technologies (e.g., fertilizers, pest management tools, and antimicrobials) by as much as 50% and promotes natural methods such as organic farming, with limited reference to the importance of working with the private sector and no mention of a specific production goal to match the conservation objectives. Without addressing production, the effort falls short. Demand for agricultural goods and services will not diminish, and the result will induce other countries to expand production to meet demand. In the end, the effort will simply shift production away from the EU rather than improving environmental performance.

The USDA Agriculture Innovation Agenda

In February 2020, USDA Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue announced the Agriculture Innovation Agenda (https://bit.ly/2MJep5O) as part of an overarching theme for the annual USDA Ag Outlook Forum focused on the role of innovation in the past, present, and future of agriculture. The purpose of the Agriculture Innovation Agenda (AIA) is to increase production while reducing the agriculture sector’s overall environmental footprint. Though the challenge goal is extensive, the AIA vision is monumental and transformative, requiring bold innovations to address emerging challenges and create new opportunities in agriculture for both producers and consumers.

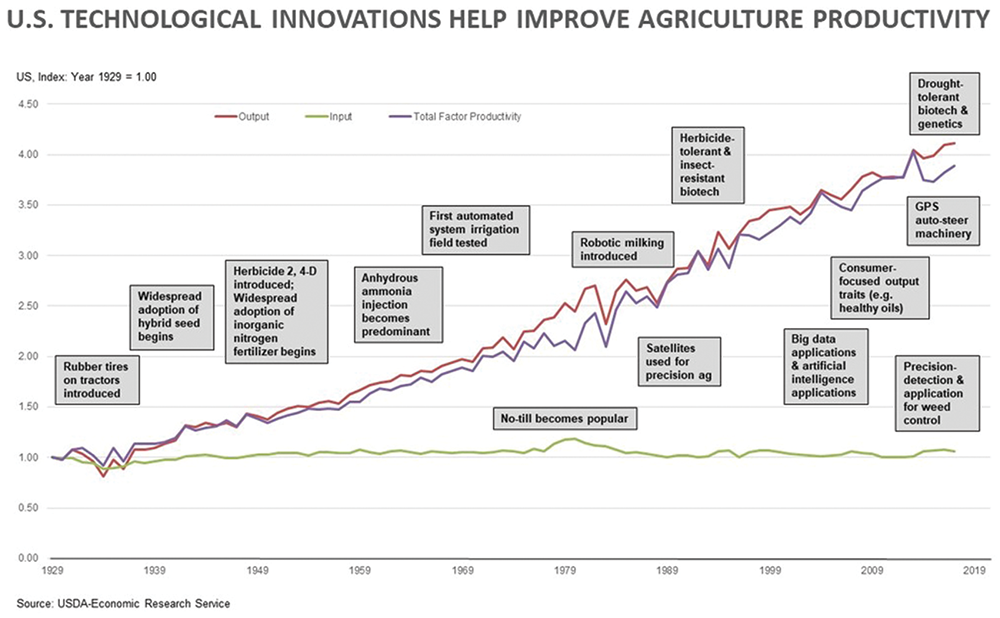

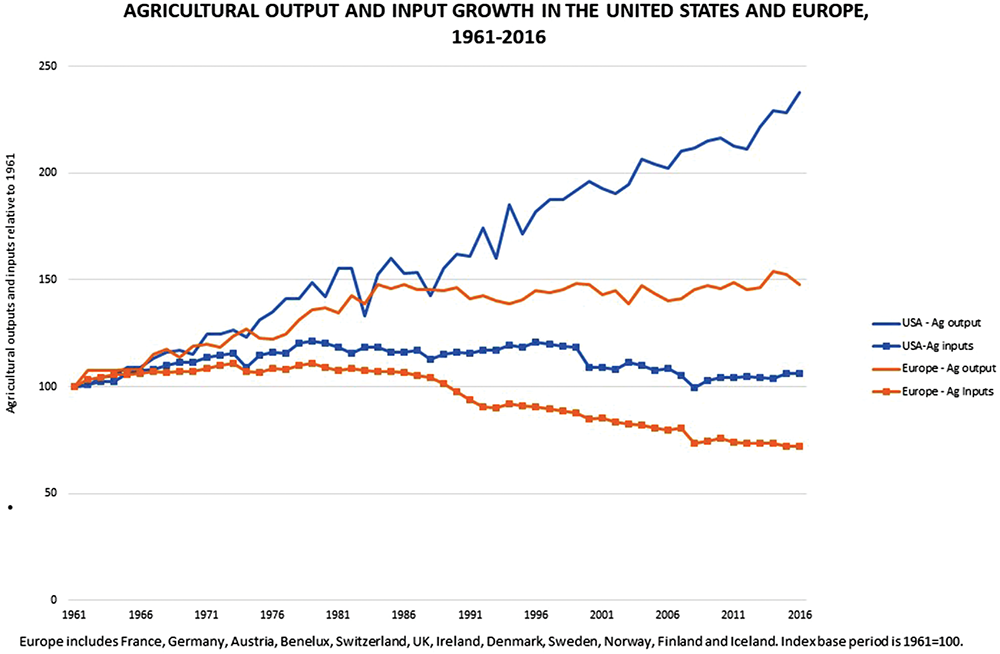

Bold innovation is not a new concept for U.S. agriculture. In less than one century, agricultural productivity has increased more than 400% (see Figure 1). It’s remarkable that the increased output over this period has been accomplished with virtually no additional inputs. The form, function, and approach to the inputs have changed dramatically through new innovations, but the aggregate level of input has not changed. Although progress has been sustained for decades, the productivity slope must steepen with sustained investments in science and rapid adoption of new technologies focused on the AIA goals and the leading indicators aligned to those goals.

Accordingly, the AIA is constructed with three workstreams:

- Research: Develop a U.S. ag innovation strategy that aligns, informs, and synchronizes public- and private-sector research to high-value discovery goals over the next 10 to 30 years.

- Programs: Align the work of USDA customer-facing agencies and integrate innovative technologies and practices into USDA programs to help fast-track their adoption by producers.

- Metrics and score card: Review USDA productivity and conservation data to develop benchmarks in areas enabling USDA to evaluate its progress and maintain accountability.

There is extraordinary potential to accelerate progress toward the AIA goals in the next era of agricultural innovation. The AIA incorporated findings from a recent U.S. National Academies of Science study (see www.nap.edu/read/25059/chapter/1) on innovations that will significantly improve agriculture and food production to construct four innovation clusters of high priority:

- Genome Design—the safe and targeted approaches to improve attributes of plants, animals, and microbes to support production AND environmental footprint objectives.

- Digital/Automation—the expanded use and application of digitized data, real-time imaging, and analytical tools to automate activities with consistent precision.

- Prescriptive Intervention—the utilization of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and advanced computing to support real-time management decisions.

- Systems-Based Farm Management—the integration of highly complex technical and management information into a framework and context enabling resilient farm management.

These innovation clusters do not represent all the innovation required to reach the AIA goals—advancements in biological, chemical, and mechanical tools will all be essential components of the toolbox. But the clusters do represent the most transformative opportunities to truly impact sustainable agriculture in the future. And, while harnessing technology is most frequently associated with increasing production, the real gains come from improving productivity, seen as sustainable intensification. By unlocking productivity gains, the potential to enable production capability for true sustainability is unlimited.

Another feature of the AIA is the direct and sincere engagement of the U.S. agricultural community and public at large. Organizations involved in agriculture (producer and consumer) were engaged and solicited for input via a U.S. Federal Register “Request for Information” to identify the most significant opportunities and challenges for agriculture. Hundreds of inputs were submitted, and many groups proactively engaged with technical experts at USDA and U.S. universities to better understand the options and potential. This engagement, known by project leaders as the “voice of the customer,” provided invaluable insights to begin construction of a U.S. ag innovation strategy, leading to the most impactful discovery targets and solution concepts that will support the AIA goal. The public sector, including the USDA research agencies and the land grant university system, will be able to focus their research, knowing the solutions are aligned with the agricultural community as well as the larger society.

Moreover, USDA recently published the USDA Science Blueprint (https://bit.ly/3s0VALr), which complements the AIA directly, outlining the key themes for building scientific capabilities within the Department from 2020-2025. Similarly, the product goals for the private sector will be informed and formulated by their business development teams with confidence that they are solving the challenges that matter to their customers and in full alignment with the goals of sustainable agriculture. The AIA actively solicits engagement from the private sector along with public–private partnerships, ranging from small start-ups to large multi-national organizations.

In summary, the AIA outlines a challenging goal for sustainable agriculture in the U.S., embraces the need for relevant innovation as the engine leading the desired outcome, and defines the framework for adoption while establishing a scorecard to define progress. The agricultural community endorses the goals, and public- and private-sector research groups are engaged and focused within a broad agricultural innovation ecosystem.

The EC Farm to Fork Strategy

The Farm to Fork (F2F) Strategy (https://bit.ly/3nltEyl) proposes a framework for a fair, healthy, and environmentally friendly food system and is cited as the heart of the European Green Deal. The F2F Strategy is described in the EC’s policy document as “a new comprehensive approach to how Europeans value food sustainability. It is an opportunity to improve lifestyles, health, and the environment. The creation of a favorable food environment that makes it easier to choose healthy and sustainable diets will benefit consumers’ health and quality of life and reduce health-related costs for society”.

The approach to achieve these goals is related to the notion that there is an “urgent need to reduce dependency on pesticides and antimicrobials, reduce excess fertilization, increase organic farming, improve animal welfare, and reverse biodiversity loss.” The EC believes the transition will represent a “huge economic opportunity” and essentially creates its brand for society and the world. Inclusive is the expectation to shift people’s diets to reduce obesity and associated food intake, which would further reduce the agricultural footprint.

Of significance to global trade, F2F that “it is also clear that we cannot make a change unless we take the rest of the world with us” and emphasizes that their effort includes policies to raise standards globally to avoid export of goods produced by unsustainable practices.

The stated goals are to reduce the environmental and climate footprint of the EU food system and strengthen its resilience, ensure food security in the face of climate change and biodiversity loss, and lead a global transition towards competitive sustainability from farm to fork and tapping into new opportunities.

The F2F Strategy further states that “all actors of the food chain must play their part in achieving the sustainability of food chain. Farmers, fishers, and aquaculture producers need to transform their production methods more quickly and make the best use of nature-based, technological, digital, and space-based solutions to deliver better climate and environmental results, increase climate resilience, and reduce and optimize the use of inputs (e.g., pesticides, fertilizers). These solutions require human and financial investment but also promise higher returns by creating added value and by reducing costs.”

As for targets and goals, the Strategy is focused on chemical pesticides because of their stated contribution to soil, water, and air pollution; biodiversity loss; and non-target impacts. The EC will reduce risk by 50% with elimination of the more hazardous pesticides by 50% by 2030. Farmers will be encouraged and/or incentivized to use mechanical, cultural, or natural control mechanisms. Similarly, nutrients are noted as another major source of air, soil, and water pollution and climate impacts that similarly has reduced biodiversity. The EC will reduce nutrient losses by at least 50% without loss of soil fertility. Integrated nutrient management action plans will be proposed along with provisions for advisory services and technologies. Noting that animal agriculture represents nearly 70% of the agriculture-related greenhouse gas emissions, the Strategy will foster EU-grown plant proteins and alternative feed materials such as insects and marine feed stocks/fish waste as alternatives to meat along with more sustainable meat production. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) concerns are leading the EC to reduce sales of antimicrobials for farmed animals and in aquaculture by 50% by 2030. A special focus on animal welfare is also noted, including production-system labeling throughout the food chain.

As for innovation, the F2F Strategy suggests that new innovative techniques, including biotechnology and the development of bio-based products may play a role in increasing sustainability, provided that they are safe for consumers and the environment while bringing benefits for society as a whole. In addition, the Strategy calls for a rapid and expansive scale-up of organic agriculture, seeking to have at least 25% of the EU’s agricultural land under organic farming by 2030. Substantial funding by member states to reach these goals is proposed to accelerate adoption of these so called “eco-schemes.”

The F2F Strategy also recognizes the need to shift current food consumption patterns to include both health and environmental viewpoints, seeking to reduce intakes of energy, red meat, sugars, salt, and fats. Moving to a more plant-based diet is noted as the goal. The EC will also determine the best way of setting minimum mandatory criteria for sustainable food procurement to ensure every public authority does its part to boost sustainable farming systems, such as organic farming.

Research, innovation, technology, and investments are noted to support the transition. The Horizon Europe (https://ec.europa.eu/info/horizon-europe_en) research program is cited as the mechanism with special focus on soil microbiome, food from oceans, urban food systems, and alternative protein sources (e.g., insect-, plant-, and microbial-based proteins). Investment via EU budget guarantees and other mechanisms are noted as mechanisms to de-risk investments by European companies along with facilitating funding access to small and mid-size companies under the auspices of the EU framework to facilitate sustainable investments.

The F2F Strategy proposes to support advisory services, data and knowledge sharing, and skill development for all stages in the food system to become sustainable. As part of this, the Strategy proposes to establish a Farm Sustainability Data Network to replace the Farm Accountancy Data Network. The intent is to benchmark each farm against regional and national standards as a means to locate and improve the sustainability of participating farmers.

Finally, the Strategy is heavily focused on ensuring the global transition to F2F standards outside the EU, leveraging the EU purchasing and import power with trading partners. This will extend to influence a broader set of objectives related to deforestation limits, import tolerances, animal welfare, and other topics on the periphery of the EU direct focus of member states.

In summary, the F2F Strategy establishes ambitious goals focused squarely on reducing the environmental impact of agriculture in the EU. Clear and direct reduction targets for pesticides, fertilizers, animal anti-microbials are noted along with the rapid expansion in organic farming and dietary shifts away from animal protein based on both health and environment arguments. The Strategy does recognize a role for innovation in supporting the transition and includes a special emphasis on trade and global standards.

Comparison of the Two Approaches

As noted, the U.S. and EU both share common goals, especially regarding any deleterious impact to the environment or production capability of the soil. Yet, their respective approaches are vastly different along with different levels of emphasis on production and productivity. In addition, the F2F places an additional emphasis on nutrition as part of the overall strategy, whereas the U.S. incorporates this focus as part of other aligned initiatives, including the USDA Science Blueprint; this comparison will focus only on the production and production capability aspects that are common between the strategies.

One of the many key distinctions is the differing view regarding the future role of technology and innovation in agriculture. The F2F Strategy puts front and center reducing conventional tools used by farmers with no mention of a risk-assessment paradigm or provision on how to replace the role and value these tools provide—certainly not before the 2030 removal timeline. Moreover, there is no significant, accompanying initiative outlined as discovery goals to create new tools (e.g., gene-edited plants to reduce pesticide use or nitrogen use efficiency) or engage directly with the private sector to develop new solutions. The AIA, by stark contrast, embraces the technologies that farmers and ranchers rely upon, but challenges the research and innovation community to enhance current methods while developing better tools—ones that allow a continuous improvement or lasting change for environmental conservation and agricultural production.

Inherent in these differences is the broader societal divergence with the role of modern science and technology between the two regions when applied to agriculture. The EU has largely abandoned many forms of “high tech” such as synthetic chemistry as a solution and seeks to demonize it with the clever political positioning of “the precautionary principle.” The precautionary principle is not based on science and restricts the introduction of a new products whose ultimate effects are disputed or unknown, deeming it too risky until it can be proven to have zero risk. This approach has been used to prevent the cultivation of biotechnology solutions that have been proven safe beyond all level of doubt after more than 25 years and billions of hectares of use in the Americas, forcing EU farmers to rely, ironically, on pesticides and conventional tillage. And now, the F2F Strategy, if implemented, will take these tools away and leave farmers with limited tools to protect their crops. Novel technologies such as gene editing that do not introduce foreign DNA are also currently rejected, proving that the reluctance is not about risk to consumers, but about an ideological aversion to all agriculture technology itself in favor of “natural farming.” The Strategy also politically contorts the legitimate notion of agroecology to an infeasible solution for addressing food insecurity. Europe, once the very cradle of science for the world, seems to have abandoned it completely, at least for agriculture—along with abandoning their scientists and their farmers, both of whom are marginalized with the F2F Strategy. Their hazard-based regulatory approach codifies their ideology, effectively seeking to declare most technological tools too hazardous while stiff-arming the private-sector innovation options.

The U.S. has embraced technology and tools as essential for progress and, with the AIA, is prepared to “double down” on the next generation of innovation. The story begins with agricultural innovators such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson but was accelerated when President Lincoln created the USDA and the land grant university system in 1862. With exceptional foresight, the investment to ensure farmers always had the best tools, techniques, and technologies was the very catalyst the U.S. needed to diversify and expand its economy; indeed, the great seal of USDA states: Agriculture is the Foundation of Manufacture and Commerce. Today, with U.S. farms operating as high-tech enterprises, only 2% of the population is directly engaged in farming, yet agriculture is in the fabric of the economy and reinforced by national, state, and local commitments to agriculture research, teaching, and extension. This is a model that has sustained the industry and enabled the progress outlined in Figure 1, including providing the talent for private-sector firms dedicated to the discovery, development, and commercialization of advanced tools. This almost 160-year system, along with a vibrant and fully developed private-sector community of innovators, will be the engine to ensure the AIA is powered for success. To be sure, the tools and technology are regulated with a risk management scheme to ensure safety, but on an evidence-based research platform, not a scheme biased with an ideological fear of technology.

Outcomes Matter

Past results tend to forecast future performance. Although both the AIA and F2F policies are relatively new, both regions have effectively embraced their principles for decades. The U.S. public- and private-sector research groups have led the world with the discovery, development, and launch of bold, new technologies to support farmers and their objectives along with the eager adoption of discoveries outside the U.S. that also benefit the cause. The EU has very capable research organizations, but its work has been limited due to the regulatory philosophy and political will so clearly averse to agricultural technology. Indeed, private-sector biotechnology powerhouse companies have virtually no outlet in the EU for many of their investments even though they have been proven safe and effective in many other regions of the world where they are in extensive use. In addition, the EU has no recognizable equivalent to the public investment in agricultural research, teaching, and extension on par with the U.S. land grant university system. In short, there is no legacy of modern innovation and no political will to create a new path that centers around technology in agriculture.

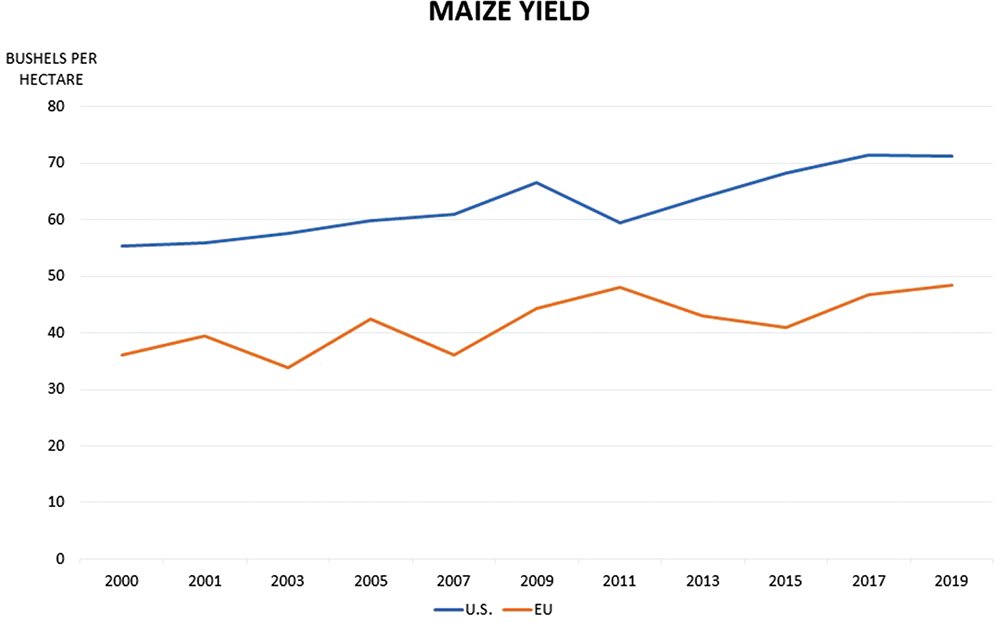

Tools and technology are not the end, but the means to an end. When it comes to differing production and conservation approaches in various region, the data tell a compelling story. Maize, a crop that has benefited greatly from a range of transformative technologies, demonstrates the comparison of approaches clearly. Biotechnology for insect resistance was introduced in the U.S. during the mid-1990s and quickly demonstrated value with rapid adoption. By the turn of the century, the positive impact of these traits and herbicide tolerance traits on yield was clearly recognized as net productivity gains with reduced complexity in weed control such that, today, the yield gap between the U.S. and EU exceeds 13% with the use of technology (Figure 2).

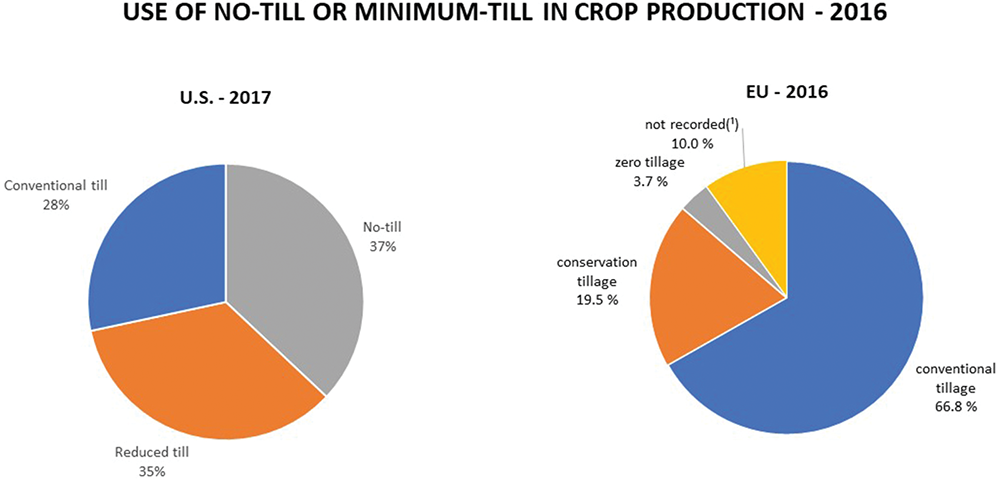

Moreover, the adoption of the technology has reduced pesticide use dramatically in U.S. maize and enabled new cultivation practices such as no-till and reduced-till, which improve soil health, reduce fertilizer runoff, lower greenhouse gas emissions, and conserve water. The level of these conservation tillage practices has reached 72% in the U.S. vs. a comparative adoption of 23–33% in the EU. No doubt EU farmers would quickly adopt these practices, but effective weed control is virtually impossible without technologies like herbicide-tolerant crops that replace conventional tillage methods (Figure 3).

Thus, the technological advances impact both production (yield) and production capability (soil health) simultaneously, which is the essence of the AIA focus on sustainable intensification.

Overall, the two regions have a different story for output and inputs (Figure 4). Total agricultural output has been on a steep, upward slope in the U.S. with similar levels of input to 1961. Total production in the EU, while rising initially, has been flat since around 1981 as they have systematically reduced or rejected technology-based inputs.

For sure, these data of past performance foretell the likelihood of success with future implementation of the AIA and F2F Strategy. The AIA builds on a long history of advancing production sustainably with ever-improving technology, and the F2F Strategy will stymie or even reverse the gains made as key tools of production are removed or limited in use.

The AIA model is one of sustainable intensification, meaning that each parcel of land should endeavor to produce progressively more output, in perpetuity, with advanced technologies. This model is the only truly sustainable approach since it minimizes the amount of land dedicated to agriculture and “releases” or “conserves” land for forestry and other conservation purposes, which expands diversity, sequesters carbon, and increases resiliency of the soil. Sustainable intensification, driven through total factor productivity growth, also conserves other inputs per output and thereby supports the production needs required for a growing world population.

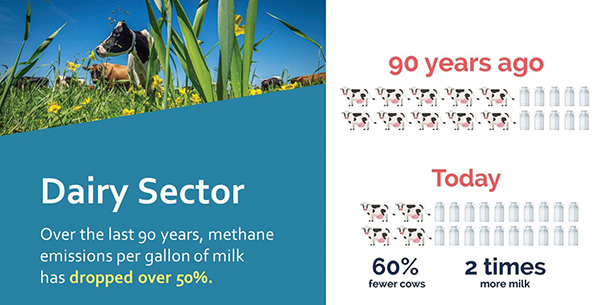

Despite the many cropping examples cited, technology-driven efficiency is even more relevant for animal agriculture. In dairy production, for example, the industry has significantly reduced the number of herds while simultaneously increasing total production and reducing related waste (https://bit.ly/35jd24g; see Figure 5). The technology has been based on genetics, feed/nutrition, and habitat along with efficiency in dairy collection, processing, packaging, and storage. The story is a picture of how to increase productivity while simultaneously reducing the environmental footprint; advanced genome design, digital tools, and systems approaches promise to write the next chapters.

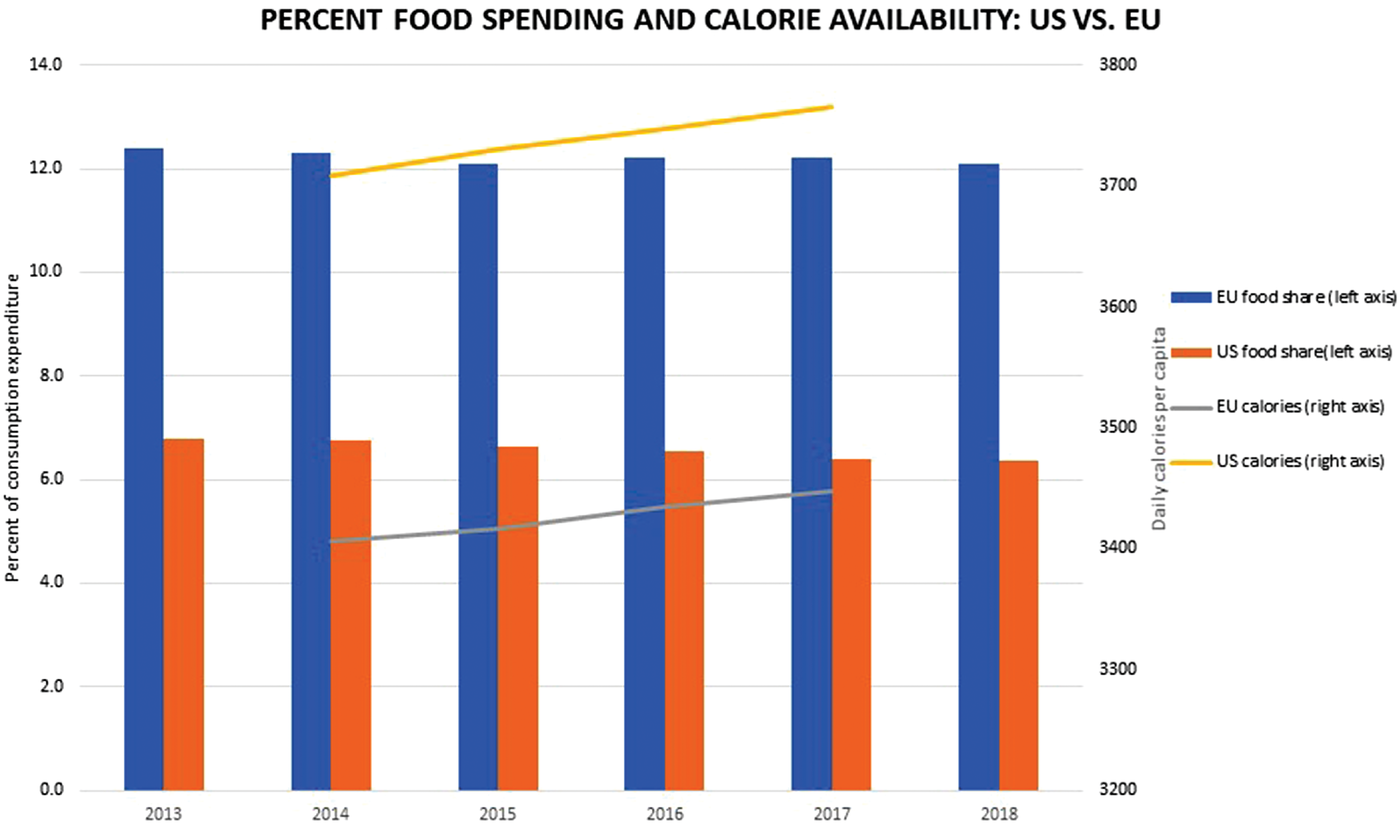

Another critical outcome of agriculture is available and affordable food. In this category, the technology-driven approach of the AIA has resulted in the average U.S. citizen spending among the lowest percentage of their income on food in the world, almost half of EU spending. And with our responsibility to help feed the world, the U.S. system produces more than 300 more calories per capita with sustainably intense production systems (Figure 6). The U.S. does not seek to impose its technology-based approach on any nation, but only seeks to ensure that science and evidence is respected and used as the basis of fair and evidence-based trade policy. Nonetheless, the U.S. seeks to support the agricultural development systems of these trading partners to enhance their economy and for humanitarian reasons. In contrast, the EC proposes to essentially require trading partners to use their approach in the F2F Strategy as a condition of trade, completely avoiding the scientific evidence and arguments or even recognizing the special technological needs that their agricultural systems require. This has devastated the prospect of many countries to produce adequate food for their own citizens or create competitive trade enterprises. The F2F Strategy encompasses the ultimate expression of global elitism.

These impacts on other nations are not speculative or without evidence. Curiously, the EC, despite its belief in the precautionary principle, had not conducted a definitive impact assessment of impacts to its own farmers or agricultural economy before publishing the F2F Strategy. However, a recent peer-

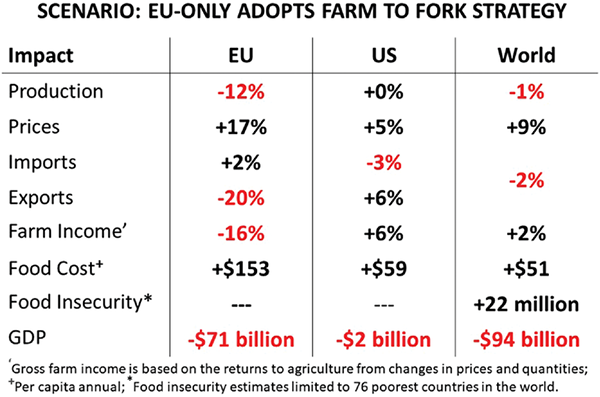

reviewed study by the USDA Economic Research Service (https://bit.ly/2XhqnWg) revealed the economic impact of the F2F Strategy based on information outlined in the public documents. The results are compelling. If only the EU adopts their proposed practices, the following outcomes would be expected (see Figure 7): reduced EU gross farm income and production, increased consumer prices, and increased global food insecurity.

Outcomes are far worse if the EU is successful in coercing trading partners to adopt the F2F Strategy. The reduction in EU agricultural production anticipated from F2F affects global agricultural production and land use. Almost all other countries increase their agricultural production, which causes them to convert land into crop production. The land tends to come from land previously used as forest as land for livestock also increases (somewhat) due to the reduction in EU meat production. The conversion of land to crop production tends to be highest for those who have the largest increase in agricultural production. For example, Oceania has an increase in cropland of 10.1%, Canada has an increase of 4.6%, and Ukraine has an increase of 4.2%. So, what may appear to be any environmental progress in the EU will be lost or neutralized globally to compensate for the F2F Strategy ramifications.

These ideological trade barriers are beyond economic; they are discriminatory and irresponsible to populations of the most susceptible nations by limiting their opportunity to produce safe, abundant, and affordable food supplies for domestic consumption and export with their productive land, ample natural resources, and safe technology. Without the ability to be self-sufficient, these nations will not develop new industries and be primarily agrarian in perpetuity.

Summary

Agriculture enabled human civilization, and modern agriculture enriched it. The development of any nation must first begin with an agrarian phase and migrate to diversification of the economy. This migration requires scale and productivity growth via sustainable intensification only made possible with advanced tools and technology based on credible science and a risk-proportionate regulatory scheme.

Affluent nations, once migrated to economic diversification, may choose a path of slowing or even reversing the continued focus on production—the EC has made that choice with its F2F Strategy. And, although the Strategy presents no evidence that it maximizes conservation and biodiversity, it will certainly harm farmers economically and thrust millions into food insecurity. The alternative is to accelerate the path of innovation, equally focused on productivity and sustainability. The USDA has made that choice with the AIA by expanding production capability and environmental performance, with a reliance on science and innovation, to create the transformations necessary. The focus is to engage farmers and energize the great infrastructure of agricultural research in the public and private sectors to discover, develop, and transfer or commercialize the tools of the future to ensure producers and consumers thrive. The discovery goals outlined in the AIA are both incremental and transformative; they describe the reality of a science and technology renaissance that agriculture is realizing.

True sustainable agriculture requires economic, social, and environmental sustainability. The EC F2F Strategy could reduce European farmers’ income, thrust 22 million more people into food insecurity, and has no conclusive science to support the environmental goals it advocates, failing the test of sustainability. The USDA AIA will increase farm productivity/profitability with less land; ensure a socially and environmentally responsible safe, abundant, and affordable food supply; and be powered by safe, science-based technologies and innovations that transform the next era of agriculture, passing the test of sustainability.

Because of the global nature of food production and trade, each nation must choose its own paradigm for its own journey toward self-reliance. For those in the agricultural research, teaching, and extension and innovation profession, whether public or private sector, stand tall with pride for the impact you have made to feed the world responsibly and be assertive in seeking new discoveries, new methods, new tools, and new technologies to ensure true sustainable agriculture is realized to meet the production and production capability challenges ahead.

Editor’s note: The views expressed in the Opinion/Perspectives section of CSA News magazine are not necessarily those of the publisher, ASA, CSSA, SSSA, and editors. Have an opinion or perspective you’d like to share? Email Send Message.

DIG DEEPER

For more information, visit:

- Agriculture Innovation Agenda: https://bit.ly/38nzLOx

- National Academies of Science Book/Study: Science Breakthroughs to Advance Food and Agricultural Research by 2030: www.nap.edu/read/25059/chapter/1

- USDA Science Blueprint: https://bit.ly/3s0VALr

- EU Farm to Fork Strategy Document: https://bit.ly/3nltEyl

- Horizon Europe Site: https://ec.europa.eu/info/horizon-europe_en

Also our podcast, Field, Lab, Earth, released an interview with Dr. Hutchins on 22 January comparing and discussing these two programs (see https://bit.ly/3tfPFmu). Find us at https://fieldlabearth.libsyn.com, through your favorite podcast provider, or by scanning the QR code below. Subscribe for free to never miss an episode. CEUs available.

Erratum

The organization and safe storage of data is critical to effective sharing and publication of research. Data organization decisions begin even before data are collected when making decisions on experimental design and the research questions to be addressed. Design your experiments with care, collect the measurements that best answer your research questions, and keep your data organized to save yourself time and frustration during data analysis. Following are three tips to help you approach data management thoughtfully throughout the research process.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.