Can the world food prize be posthumous?

Before 56 years had come and gone, a career and life ended, long before its time. It was 26 Jan. 1943 when Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov passed away in Russia’s Saratov City Prison; no longer seen by those whom he worked with and who admired or emulated him. The General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin, had grown impatient with the unsolvable problems in agriculture, and Vavilov was the perfect person to blame. This accusation, among others, came even though Vavilov was not the food shortage cause, nor had he been given sufficient generational time to address plant stresses contributing to the shortages.

Even though Vavilov’s life ended 20 years sooner, on average, than that of other plant explorers, he still traveled and collected plant material up to the end of his life with a final total of collections made personally from five continents. In fact, the very moment he was arrested by Russia’s secret police he was conducting a botanical expedition in the western regions of Ukraine.

A Lasting Legacy

Just eight years before his death, in 1935, Vavilov finished editing a three-volume publication on The Scientific Basis of Plant Breeding, working faithfully to produce a document of 2,500 pages. It was Vavilov’s dream to translate his own chapters of the publication for the benefit of his English-speaking readers. Unfortunately, he was unable to conduct this task. By 1951, it was partly published in English, under the title, The Origin, Variation, Immunity and Breeding of Cultivated Plants, Selected Writings of N.I. Vavilov.

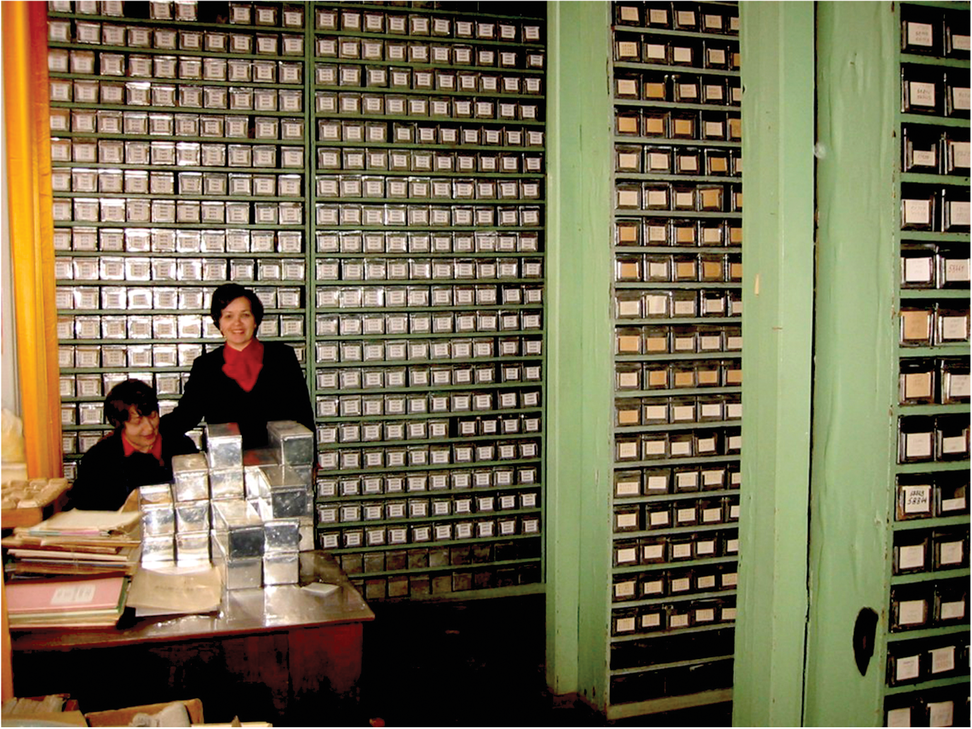

As one acknowledgment of such contributions, and for his foresight and management of the gene bank in St. Petersburg, its name changed to The N.I. Vavilov Institute of Plant Genetic Resources (VIR). As of 2021, the total germplasm accessions held by VIR had climbed to 330,941, representing “the world’s diversity of plants.” Vavilov also wrote dozens of scientific books and published more than 400 articles. The Soviet government recognized his leadership capabilities, and during his lifetime, Vavilov held at least 18 positions, either as professor or director of various institutes.

For 12 years after Vavilov’s death, no one was allowed to speak his name, his books were removed and destroyed, his lessons could not be taught, and his final resting place remained unknown. In 1955, following Stalin’s death, President Nikita Khrushchev ended Vavilov’s isolation by overseeing the rehabilitation of his name by the Soviet order. Once done, Vavilov’s name appeared on buildings and stamps and was the inspiration for scientific conventions and conferences, both in Russia and abroad.

It was rapidly seen that Vavilov left a history not only of theory, but of management, leadership, and inspiration, which carries on to this day. However, even with the reinstatement of his name, and his scholarship and achievements, he could not be considered for World Food Prize nomination at the time as he died 44 years before the first World Food Prize was awarded.

However, Vavilov’s personal characteristics were acknowledged by other awards given during his life, and more recently, posthumously for contributions to the study and collection of genetic resources, and for his contributions to geography, plant collection, genetics, and plant breeding.

As one example, Drs. Hawkes and Harris organized the N.I. Vavilov Centenary Symposium in 1987. In the preface to the proceedings it read, “Not only this—the whole movement of crop genetic resources conservation as a necessary prerequisite for the new more resistant and productive varieties needed now and, in the future, can be clearly traced back to Vavilov’s seminal ideas.” Since this date, innumerable studies have shown the value obtained from introgression of traits from genetic resource collections into elite or otherwise productive varietal backgrounds.

For the 100th anniversary of. Vavilov’s birth, most of his fundamental works were republished with the support of the government of the USSR in Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Saratov. Articles by Vavilov were also published in English in 1992 under the title Origin and Geography of Cultivated Plants, and in 1998, an English version of Vavilov’s book, Five Continents, was published.

World Food Prize Considerations

As for the World Food Prize, should someone from their institute nominate Vavilov, then his contributions would need to address the following: First, achievements by Vavilov “must be shown to have resulted in a demonstrable increase in the quantity, quality, availability of, or access to food for a large number of people.”

Second, “the impact of this achievement must be measurable, quantifiable, or otherwise demonstrated either in terms of reduced poverty, hunger, or suffering; or enhanced health, nutrition, quality of life, and well-being.”

Third, Vavilov’s work “must be clearly show that this increase in food security was the direct result of the specific actions and activities of the nominee, i.e., without his or her specific accomplishment, no change would have occurred.”

Fourth, the World Food Prize guidance states that, “A nominee must be living and in sufficiently good health to attend the World Food Prize Award Ceremony.” Upon hearing this, can anyone image Vavilov not wanting to be in attendance? Would he not once again desire to sit among his colleagues and friends from around the world and commiserate like the great learned person, waiting for his intellect to be called into battle and for one more round of scrutiny on the origins and diversification of crop plants?

An alternative would be to acknowledge the role of genetic resources in crop improvement and nominate Vavilov and other individuals whose careers address the criteria above. To produce such a nomination, a group of specialists could determine what benefits accrued from seedbanks; secondly, demonstrate how such work has contributed towards human well-being; and thirdly, how genetic resources contribute to food security. Finally, in nominating Vavilov with other worthy nominees, the fourth criterium could be met.

When Charles Darwin passed away, he was to be buried in St. Mary’s churchyard. But no sooner had word spread of his passing that Sir Francis Galton, a staunch hereditary genius, and Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, botanist and foremost evolutionist, gathered a petition that led to Darwin, who, should he wake from the dead, find himself in Westminster Abby, “England’s shrine of highest order.”

Must Vavilov be left alone, isolated, in his grave, or might he be celebrated once more for the causes he believed in? Would not such a nomination ensure that Vavilov’s life retains such meaning for the coming generations?

Acknowledgments

The author would like to gratefully acknowledge pre-publication discussions on Vavilov and the impact of genetic resources with Drs. Paul Gepts and Shuyu Liu. Special thanks as well to Dr. Igor Loskutov for additional informational and corrections.

Members Forum is a place for ASA, CSSA, and SSSA members to share their opinions and perspectives on any issue relevant to our members. The views and opinions expressed in this column are not necessarily those of the publisher. Do you have a perspective on a particular issue that you’d like to share with fellow members? Submit it to our Members Forum section at Send Message. Submissions should be 800 words or less and may be subject to review by our editors-in-chief.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.