What drives soil water memory and persistence?

- The soil “remembers” events that are out of the ordinary, like a heavy rainstorm in the middle of a drought.

- Soil water “memory” refers to the time after an unusual event before the soil returns to its previous state and has impacts on soil conditions and even weather after an event.

- Vadose Zone Journal research highlights how modeling soil water memory can help scientists understand long-term impacts of big weather events.

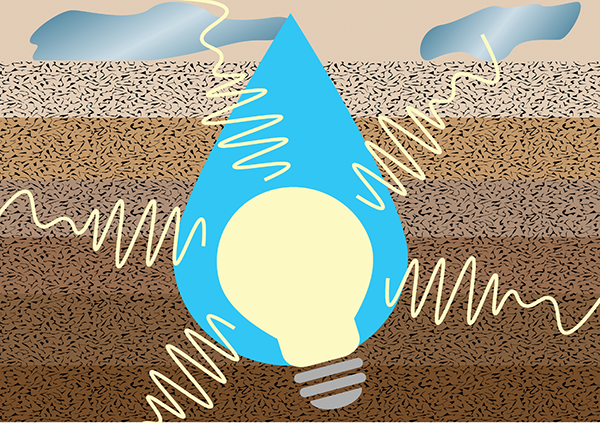

A rainstorm batters a field of soil for hours, and the field absorbs a portion of the water. The next day the soil appears wet, and it appears that way the next day or even for a whole week, until it finally begins to return to its previous dry state. The amount of time it takes for the effects of the rainstorm to dissipate is called “soil water memory.”

But what influences how long a soil’s “memory” is? And why does the length of the memory matter?

Elin Jacobs, a research assistant professor at Purdue University, and her colleagues are working to parse out what drives soil water memory and persistence, the latter being the time an area spends above or below a certain soil water threshold. Their recent work in Vadose Zone Journal points to fewer leading influences rather than more (https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20050).

Soil Water Memory

Jacobs says that soil water memory refers to the length of time before the effects of an unusual hydroclimatic event, such as heavy rainfall or very dry period, begin to subside. The soil “remembers” that anomaly for a relatively long period—weeks, sometimes months—even after weather conditions may be back to normal. Scientists measure soil water memory by analyzing time series in two ways: either by measuring soil water storage or, as in this study, by modeling.

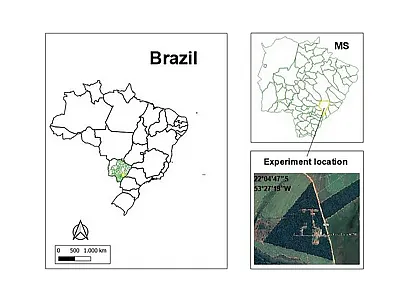

Using simulated data on soil water storage across the U.S. Midwest, they tried to see what patterns in soil water storage dynamics exist over time in areas with different soil and vegetation characteristics. The simulations combine real and modeled climate data. In previous studies, they compared their simulated data against actual measured data at all the study sites, finding it to be in generally good agreement.

“Soil water storage is an important link between the atmosphere and earth’s surface and drives a number of processes including carbon and nutrient cycling, vegetation and crop growth, and even weather,” Jacobs explains. “The amount of water stored in soils varies over time and can be problematic if levels are unusually high or low for extended periods of time, for example, during droughts or floods.”

In something resembling the butterfly effect, differences in soil water memory have impacts far beyond soil staying muddy or dry. Soils return water to the atmosphere through a process called evapotranspiration, which can affect seasonal weather and drought forecasting.

"In something resembling the butterfly effect, differences in soil water memory have impacts far beyond soil staying muddy or dry."

“As an example, if the landscape is very slow to replenish soil water storage after a drought, evapotranspiration rates may be lower than normal—which in turn, impacts cloud formation and, consequently, rainfall,” Jacobs says. “This, in turn, can potentially exacerbate or extend the period of a drought further.”

The Big Three

In their work, they examined three broad areas that they thought could affect soil water storage across the Midwest: soil properties, vegetation, and hydroclimatic forcing. These are the factors that can impact the level of water held in soil far beyond the duration of a storm or drought itself.

Soil texture, clay content, and organic matter all affect how much water a soil can store. However, it can be difficult and often counterinitiative to define a certain soil based on long or short memory.

“A soil with low water-holding capacity is likely to drain quickly after a rain event, thus having short memory of that storm,” Jacobs explains. “But that same soil may be slow to replenish following a drought, therefore having a long memory of that event.”

The researchers also examined the vegetation and land cover patterns of the study area, which includes crops like corn and soybeans, grasslands, and forests. For example, croplands are often engineered to have better drainage, and wetlands are sometimes filled in or drained. These landscapes are all managed differently to meet various needs for food and fiber production. These differences are often viewed as a major obstacle in understanding larger-scale hydrologic processes.

A third factor was “forcing,” which refers to factors that exist outside of the landscape that impact soil water storage. The scientists studied the two variables of rainfall and net radiation as forcing factors in their study. They focused on daily, seasonal, and annual fluctuations of these variables across the study region of approximately two million square kilometers.

Predicting a Drought

The team’s data illustrates that when making drought predictions and risk assessment, not all three of these major factors are created equal. Their findings show that landscapes that may differ in vegetation and soil characteristics have very similar patterns of soil water dynamics. They find that hydroclimate—especially frequency of rainfall—is the key driver of these dynamics.

“This isn’t too surprising since hydroclimate largely determines the type of biome a certain region can support,” Jacobs says. “Because climate patterns are less heterogeneous than soil and vegetation patterns at regional scales, this suggests that…drought prediction and risk assessment could be based on less complex models based primarily on hydroclimate, which is easier to measure than soil water storage. Persistence of hydrologic conditions is strikingly similar across all locations in the study area, implying that predictions of droughts, for example, are feasible.”

"drought prediction and risk assessment could be based on less complex models based primarily on hydroclimate, which is easier to measure than soil water storage."

While many think these predictive models need to have multiple complex variables, Jacobs says their work shows that for soil water storage, less may be more.

“In the case of soil water storage, we would argue that we don’t always need to predict the exact amount of water available in the soil at any given time, but rather focus on the probability, or risk, to exceed drought thresholds,” she says. “It can be used to evaluate the probability of something like drought, which may inform decisions on the type of crop that is suitable at a certain location.”

"we don’t always need to predict the exact amount of water available in the soil at any given time, but rather focus on the probability, or risk, to exceed drought thresholds"

Related and follow-up studies by German collaborators have extended this analysis to examine similar hydrologic dynamics in Europe, Jacobs adds. The work has shown that across that continent, climate forcing also drives large-scale processes, such as the movement of nutrients that can contaminate coastal ecosystems and shallow groundwater. They also found it impacts the connectivity of wetlands, which in turn affects the ecological dynamics and resilience of amphibians that inhabit those wetlands.

Some future directions of this work include looking at how the timing of drought is important and how more powerful statistics can assist in examining meaningful drought and flood thresholds.

“We live in the Midwest and work at a major land grant university, so this work is very important and personal to us,” Jacobs says. “This study showed that long-term evolution of hydrologic processes is dominated more by large-scale climatic drivers, with land cover and soil properties having more of a secondary influence. Our analyses have important implications to crop production and resilience of ecological systems in our region. Hopefully, our work can be used to identify and predict drought and flood risk to be better prepared for such events.”

Dig Deeper

View the original article, “Drivers of Regional Soil Water Storage Memory and Persistence,” in the Vadose Zone Journal at https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20050.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.