Taking stock of soil microbes with qSIP

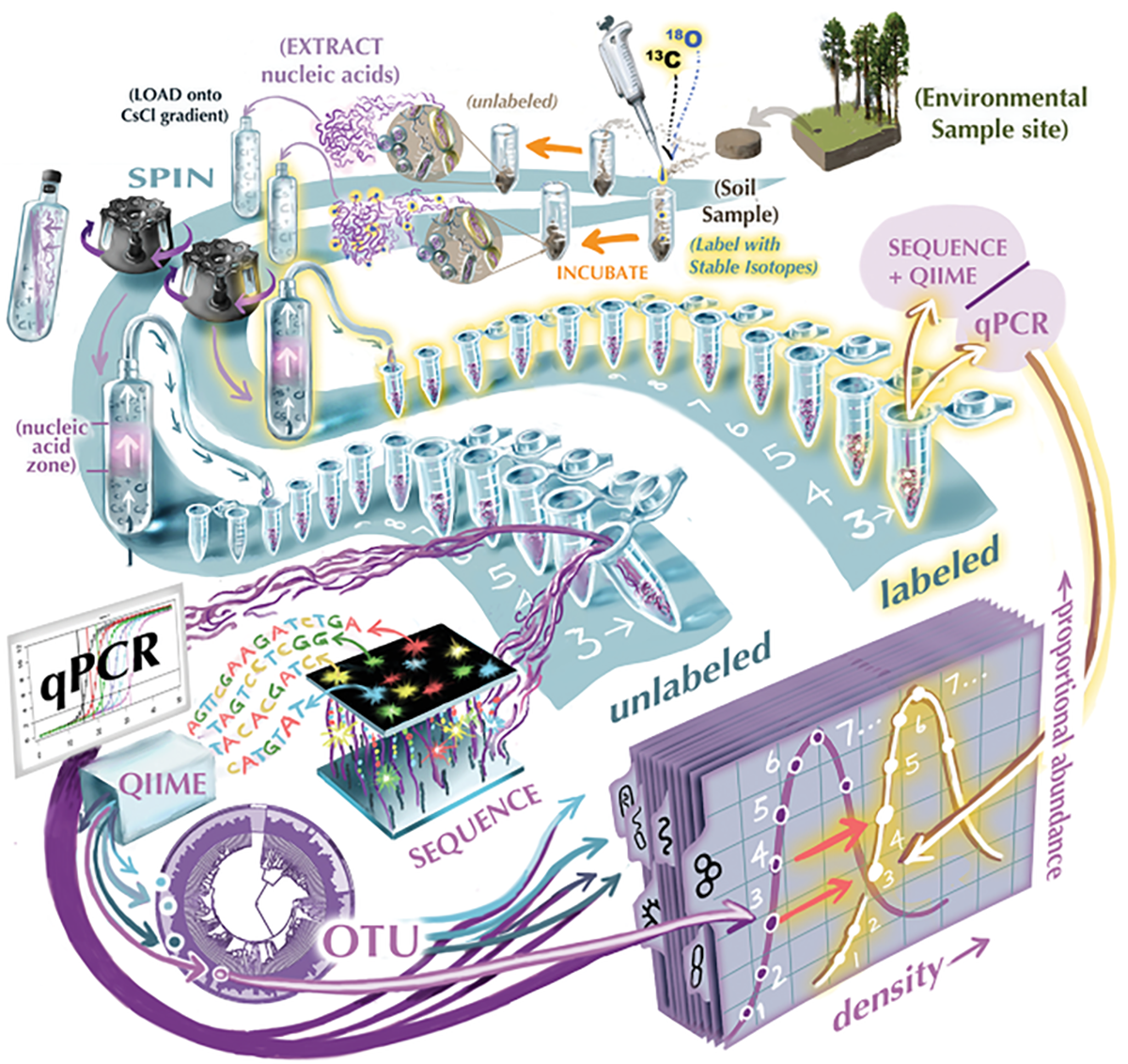

- Quantitative stable isotope probing (qSIP) is a technique innovated by researchers at the Center for Ecosystem Science and Society (Ecoss) of Northern Arizona University.

- The technique, unlike plain old SIP, allows researchers to see quantitative growth rates of individual microbe species within the soil, rather than just qualitative data showing whether they are growing.

- The technique is a big step toward better understanding how microbes interact and network within the soil.

Bram Stone's presentation caught my eye with two things: The “great plate count anomaly” and a “rainbow plot.”

Last November, drinking my umpteenth cup of coffee in a window-lined room overlooking San Antonio, I listened as Stone spoke to a crowded room of ASA–CSSA–SSSA Annual Meeting attendees. He discussed his work as a newly hired postdoc at the Center for Ecosystem Science and Society (Ecoss) at Northern Arizona University.

A microbial ecologist by training, Stone was hired to analyze raw experimental data. One such source of data is a laboratory technique for examining the way soil microbes grow and interact called quantitative stable isotope probing (qSIP).

A team led by Bruce Hungate and Egbert Schwartz at Ecoss piloted the technique in 2015 (https://bit.ly/39mSAQz). A riff on plain old stable isotope probing, qSIP takes SIP and gives it greater power to show how microbes interact in the soil.

The technique gives researchers greater insights into how best to harness the power of microbes for carbon sequestration, increased soil health, and better plant growth.

Soil Microbes

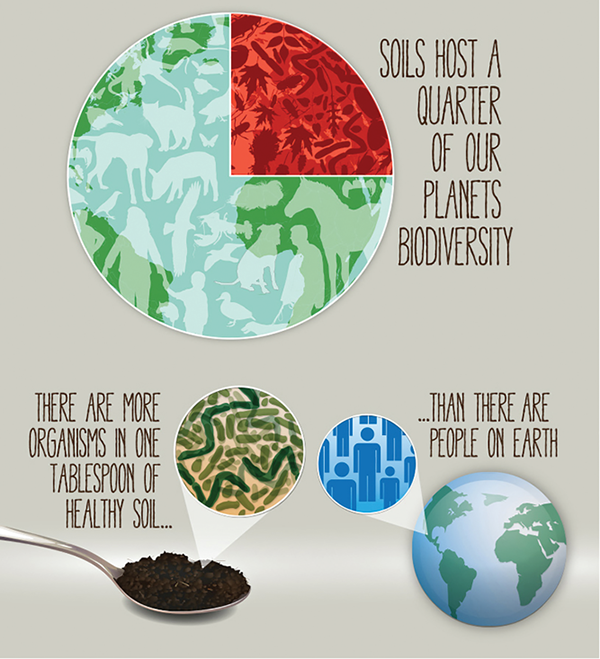

A single gram of healthy soil contains somewhere in the neighborhood of one billion bacteria, with protozoa, nematodes, and fungi to boot (https://bit.ly/2WIITXU).

Soil ecosystems are complex with individual species serving highly specific functions. Soil microbes are responsible for fixing nitrogen for plant use. They help sequester carbon from the atmosphere. They help create healthy soil structure and develop mutualistic relationships with plant roots (https://bit.ly/2P1ESJK).

They are the very foundation of healthy soil, but little is known about how specific taxa function outside of a culture plate in the lab—their behavior as a complex network, in situ, has thus far been impossible to replicate in culture.

Described by Staley and Konopka in 1985, the “great plate count anomaly” refers to the vast difference in microbial counts when they are cultured on a plate in the laboratory compared with the number visible in a fresh soil sample under a microscope (https://bit.ly/39EvbdO).

It was in light of this anomaly that Stone situated qSIP. Unlike classic culture studies, qSIP gives researchers the power to measure growth rates within a soil sample where microbes actually reside. Coupled with the power of genome sequencing, qSIP is a means for researchers to see which bacteria are present in the soil and how they grow and interact over time.

But to understand why qSIP is so important for the future of soil health, we must first understand its predecessor: SIP.

Stable Isotope Probing

In 2000, a team from the United Kingdom coined a clever method to examine the nutrient use of microbes using “heavy” stable isotopes, like 13C or 18O (https://go.nature.com/3huoQo2).

By incorporating a distinct stable isotope in the nutrients supplied to microbes, a researcher can measure if that nutrient is taken up by a group of microbes over time.

The researcher incubates the treatment group with a compound that includes a labelled, heavy isotope of nitrogen, carbon, or oxygen. After a set incubation period, the microbial DNA from the sample is extracted, amplified, and spun down in an ultracentrifuge tube through a special solution.

Like in gel electrophoresis, the DNA is separated into distinct bands based on density. Unlike gel electrophoresis, heavier bands move farther through the tube.

The researcher then extracts the DNA from these distinct bands and sequences it, working under the assumption that bacteria in the “heavy” fraction (the one farther down the tube) are growing, active species. The “light” fraction includes the non-growing microbes.

By incorporating heavy isotopes into specific compounds, researchers can see which microbes are using it for growth, and which are not. For example, if researchers incubate a soil sample with heavy methanol (13CH3OH), they know that organisms in the growing fraction are capable of digesting that compound (https://go.nature.com/3jM6TmE).

But the technique has limitations: for one, organisms with more guanine and cytosine in their DNA already skew heavier than those with adenine and thymine. It also creates a “binary separation” between growing and non-growing groups and prevents researchers from seeing the growth rates of a specific taxon (https://bit.ly/39mSAQz).

“It's like looking at the results of an election in a state and just seeing the total number of votes per party,” Stone says. “It doesn’t give you any insight into the demographics of the voters. You can’t even guess why they voted the way they did.”

Quantitative Stable Isotope Probing

Enter qSIP.

Rather than creating just two groups—a growing and non-growing fraction—qSIP divvies microbes into taxon-specific groups based on their molecular weights. The technique creates more separation by molecular weight between the groups, giving researchers greater insight into how much organisms are growing within the soil under a given set of conditions.

Simply put, qSIP gives you the “demographics” of soil microbe growth.

“The old method tells you which organisms are growing, but it doesn’t tell you how much they’re growing,” Ember Morrissey says. A former postdoc at Ecoss and author on the pioneering 2015 paper, Morrissey is now an Assistant Professor of Environmental Microbiology at West Virginia University, where she uses qSIP in her lab.

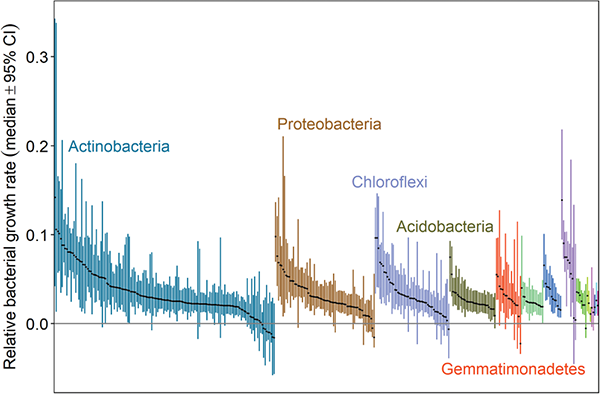

Sometimes, Stone visualizes the range of growth rates shown by these bands using a “rainbow plot”—one of the parts of his talk that caught my eye last November. In the plot, members of the same phylum are shown in the same color, with dots in the center showing the median growth rate for each bacterial taxon. The researchers run multiple trials for each sample, creating confidence intervals on either side of the median.

The rainbow plot gives the researcher insight into which groups are taking up the medium they were fed as they incubated and just how quickly they are growing. Finally, researchers can see just how organisms grow under certain conditions within the soil, instead of in a culture.

Improving Soil Health, Carbon Flux

The technique is not without its drawbacks.

“It can get really expensive really quickly,” Stone says. “When you take those two bands [i.e., the light and heavy fractions] and break them into 20, then you have to sequence all those fractions. And when you have three to five replicants of each, some without stable isotopes, you have to sequence all those, too.”

Morrissey mentions that training graduate students in statistical analysis of qSIP data also takes some time. “There's a definite learning curve,” he acknowledges.

Despite the costs, other labs across the nation and the world are beginning to use the method, including researchers at Cornell University, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Both Morrissey and members of Ecoss are refining the technique and using it for further study. One such example is work connecting bacterial phylogeny with their growth rates using qSIP (https://go.nature.com/39B51IX).

“Because there's such great microbial diversity, we haven’t characterized it all, yet,” Morrissey says. “If we can find these phylogenetic patterns, we can use that to predict the function of unknown organisms. So you can say, if it's in a certain family, and you know what other members of that family do, then you can make a pretty good guess that [unknown organism] will do the same thing. It's a really valuable tool to help us deal with the immense diversity of microbes.”

Morrissey is currently using the method to examine nitrogen uptake by bacteria in agronomic soils.

“If we know which organisms are taking [nitrogen] into their biomass, we can foster their growth,” he says. “Then, as they die and release nitrogen back into the soil, we can keep the N there rather than just applying it as fertilizer and losing it through runoff or leaching.”

The creation and application of biofertilizers—microbes that function like fertilizer in the soil—is a promising area of research. Other opportunities include inoculating soil to help plant species thrive, focusing on microbe health in those species that play a role in carbon cycling and creating methods for taking qSIP measurements in the field.

In any case, qSIP marks a notable innovation in helping us understand exactly who the major players are in microbial communities. The work completed by dedicated researchers, with a focus on the smallest members of the soil ecosystem, could help us find better fertilizers, grow healthier plants, and take care of the atmosphere of the earth we’re lucky to call home.

Dig deeper

Watch Bram Stone's presentation, “Probing the Quantitative Ecology of Soil Bacteria,” at last year's Annual Meeting, at https://bit.ly/33OSb8S.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.