Predictive agriculture: Crop modeling for the future

- An upcoming Crop Science special section on predictive agriculture brings together invited papers from a wide range of disciplines.

- Crop modeling systems can be used to predict yield, manage inputs efficiently, and explore outcomes over time when changes are made in a field.

- New methods of crop modeling can also integrate breeding, agronomy, and production.

We can go back in time; we can go forward in time. We can make the impossible possible. You cannot run an experiment with 10,000 combinations of different systems, but you can do it through modeling,” Sotirios Archontoulis says.

Archontoulis, an associate professor of integrated cropping systems at Iowa State University, is referring to crop modeling. This computerized method of data crunching takes the formulae and knowledge of a library of agricultural, meteorological, and hydrological textbooks and condenses them into a system of algorithms.

Crop modeling is just one of the foci of a newly published Crop Science special section on predictive agriculture. A swath of invited papers from leading researchers in predictive technologies across agricultural disciplines, the special section includes studies on phenotyping techniques, genomic prediction, and scaled-up crop modeling systems.

What do all these papers have in common?

At one scale or another, they use data to peek into the future, helping stakeholders at all levels of agriculture make more informed, efficient decisions. Here, we will look at two papers in the section that deal with crop modeling.

Crop Modeling

From its inception, agricultural modeling has sought to unite the broad facets that affect production, from economic drivers to management practices to local environments and crop species themselves. Some of the earliest agricultural system studies have been attributed to Earl Heady and his students (Jones et al., 2017). Heady focused his efforts on creating mathematical models through algebraic functions to help producers make economically sound decisions (Heady, 1957).

The fundamental goals of crop modeling have not changed much over 60 years of research, but computational power surely has. Mark Cooper, the Chair of Crop Improvement at the Centre for Crop Science at the University of Queensland in Australia, points to the massive strides in computing power that have been made in the past 10 years alone.

“When we first tried to do the types of computations involved in simulating whole breeding programs, it required very customized hardware and software; we had to develop these ourselves” Cooper says. “You could easily contemplate needing an investment of a hundred thousand dollars or more just to run a simulation. Whereas today, you can get the same simulations down to the price of a cappuccino. It's gone from something we were just dreaming about over coffee to something you can actually do that's equivalent to the cost of the cup of coffee you have while you design your next simulation experiment.”

With this surge in computational power, scientists from the beginning of the agricultural chain to its very end are reaping the benefits. For plant breeders, better genomic prediction coupled with advanced phenotyping means not all promising genotypes created in a breeding program need to be widely tested in the field to get a first assessment of their potential.

“Any time we can use a tool to help us understand what we're going to get in a plant cultivar without actually having to evaluate it in the field, that increases the efficiency an enormous amount,” Natalia de Leon says. “You just evaluate the most promising subset of materials based on these prediction models.”

The technical editor of the special section, de Leon is a professor specializing in plant breeding and quantitative genetics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

At a larger scale, prediction models may help farmers understand how to implement the most efficient management practices for a certain genotype in a certain environment. This three-way interaction of genotype, environment, and management is the basis for experimentation in crop modeling programs.

Modeling programs, in the simplest terms, are suites of algorithms that describe what is happening in the field at every level. There are equations for nitrogen use, carbon pools, phosphorus, water inputs from rain and irrigation, and descriptions of plant growth itself.

But instead of just taking data at single points and finding outputs, modeling systems run these algorithms over simulated time, generating continuous outputs based on starting inputs.

Heather Pasley, a post-doctoral researcher in Sotirios Archontoulis's Lab at Iowa State University, describes the way the model uses inputs to generate predictions.

“It's a series of variables that feed into each other,” Pasley says. “If you add nitrogen to the soil, that will go into the nitrogen module, which interfaces with existing nitrogen in the soil, along with carbon and the plant itself. So it feeds into the plant, which will again feed back into the soil. It's all of these inter-locking sub-modules that, when you put in any single input, it's not just going to lead to one output, but a whole system of outputs that feed back into itself.”

The idea, then, is that given accurate starting data, the model can predict the outcomes for the soil, crop yield, and water balances of a field at the end of a season. The more researchers can input about their management practices, crop genotype, and environment, the closer the match between the prediction and reality.

Likewise, models can be used to work backward and see how changes in management might have affected outcomes from a previous growing season.

“The only way to answer this question is to use modeling. To go back in time,”Archontoulis says. With information about the past growing season's weather and environment, models can show farmers how changing one input—nitrogen, here—may have led to different yield outputs.

Archontoulis and his team tested one existing crop modeling system—APSIM—and published the results from their four-year field study in the special section.

APSIM for Modeling Yields and Nitrogen Use

APSIM is short for “Agricultural Production Systems sIMulator.” Developed and hosted by the APSIM Initiative (AI) in Australia, the software is free to download and open source—that is, anyone can dig in and see the code running the show (Holzworth et al., 2014).

The publicly available source code is overseen both by a Steering Committee and a Reference Panel. The Reference Panel, of which Archontoulis is a member, is a group of scientists that evaluate code submissions and determine whether they will be added to the next release of the software. The Steering Committee ensures that the program follows its strategic plan.

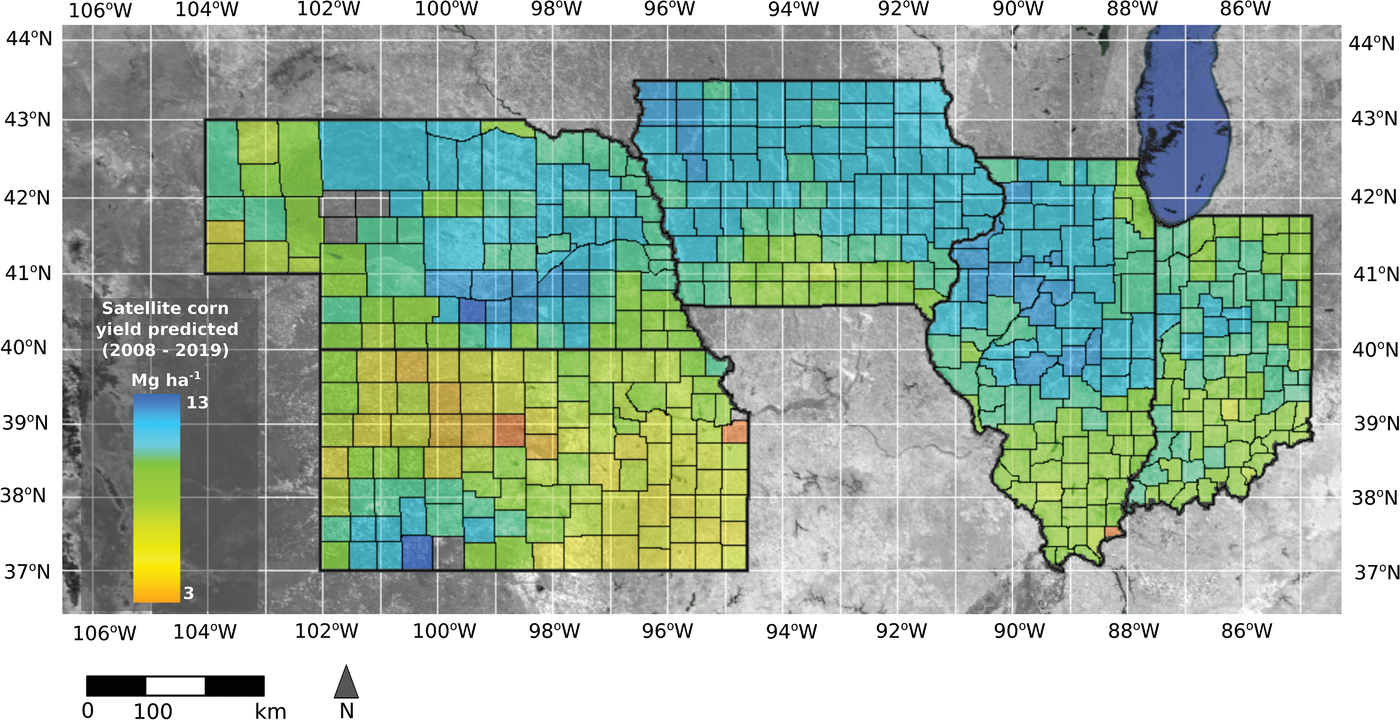

Archontoulis and his team put APSIM to the test (https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.20039). They sought to predict maize and soybean yields, climate and crop life cycles, and soil water and nitrogen dynamics in the U.S. Corn Belt. What makes their study unique is the sheer amount of experimental data they collected as a means of testing the reliability of model outputs.

Over the course of four years at 10 different field sites in Iowa, the team collected data on crop growth, soil metrics, weather, and management inputs like water and fertilizer, amassing data for 94 unique site by year by management combinations.

“In the majority of experiments, you plan the experiment, plant the crop, go out and harvest, and get the yield,” Archontoulis says. “Our approach was way different. We were going to the field every 10 days or so, getting plant samples, root samples, soil samples.”

All this sampling meant massive quantities of data the team then used to both test APSIM's models and calibrate them for accuracy. They could see how model predictions from the beginning of the season aligned with actual data from the field as time went on.

The team works with computer scientists to turn real-world outcomes into translated changes in the modules that make up the modeling system. For the Archontoulis Lab, current Ph.D. student Isaiah Huber serves as the resident computer programmer.

Huber worked closely with Pasley to develop a better module for waterlogging stresses on crops. Paradoxically, the Iowa field sites have a complicated relationship with water. In dry years, actual yield was higher than the model predicted. In years with more rainfall, the model over-predicted yield.

It all comes down to the water table. In drought years, corn crops accessed the shallow water table at many of the sites and produced a higher yield than anticipated despite minimal rainfall. In wet years, the shallow water table resulted in waterlogging stresses on crop roots that decreased yield.

“The water table provides an additional source of water that can affect plant and soil processes in different ways. It's something we've ignored in the past when we were doing predictions,” Archontoulis says.

So the team mined existing literature for data and placed sensors in Iowa wells to gather more information. Their work was used to add new mechanisms (in the form of algorithms) into the model to accurately simulate fluctuating water tables and their impacts on crop production and water quality.

This is just one example of the massive amounts of experimental data collection necessary to develop strong models. “To build better models, we need better data,” Archontoulis says, “not just data on crop yields.”

After meticulously comparing four years of experimental data to APSIM predictions throughout a crop season, the team found that the most accurate yield predictions for Iowa fields were those taken in September at the end of the season, followed by predictions from May—the very beginning of the planting season. Predictions from June and July were most susceptible to weather fluctuations, leading to less accurate results.

The team found that yield predictions in May are more accurate than mid-season predictions in the Corn Belt. This could be because, in this region, the water table buffers against the uncertainty inherent in summer precipitation. In other regions, where the water table does not provide a constant source of water, precipitation changes may more heavily influence yield outcomes.

In short, the team has constructed a study that lays the foundation for future use of APSIM as a predictive tool in the United States.

Genetic Gain and Gap Analysis

Another paper published in the special section used a crop growth model to analyze genetic gain and yield gap analysis. Led by University of Queensland's Mark Cooper and co-authored (among others) by Charlie Messina, research scientist and distinguished fellow at Corteva Agriscience, the study seeks to integrate breeding and agronomy through modeling (https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.20109).

There is often a disconnect between yields anticipated by breeders and actual yields produced on farm. This “gap” between projected and actual yield could be due to differences in the environment compared with target environments used by breeders. It could also be a product of management practices on farm.

Using the crop growth model, yields were predicted for different hybrids while carefully controlling management conditions and inputting known or anticipated environmental conditions. The team found that its model could, indeed, help breeders better understand maize hybrid performance in the field without actually testing them in the field.

“This is an opportunity for us to realize genetic improvements on farm more rapidly,” Cooper says. By improving our predictive capabilities and reducing our reliance on extensive in-field tests of all promising hybrids, efforts can be focused on the most promising subset of hybrids in the most relevant environments. More focus on management and environment at the beginning of the breeding process means a smaller “gap” when hybrids make it to farmers at large.

Cooper describes traditional breeding processes like a relay race where breeders hand off new genotypes to agronomists and crop physiologists for testing in different on-farm conditions.

“Now, we have the ability to connect them all together,” Cooper says, “so the questions that the agronomists and breeders are asking can be asked simultaneously at all stages of the process.”

The study is unique in that it lays the foundation in practical techniques for testing highly controlled management practices against modeling systems, bridging breeding and agronomy. Cooper and his team had to come up with ways to carefully control water, fertilizer, and plant population densities and measure important soil variables. The more accurate the inputs when compared with the field, the better the prediction capabilities.

“I think we came up with a lot of creative solutions that will help people testing these ideas moving forward,” Cooper says. “But in a few years, I think they'll look back on this and say, ‘That was pretty interesting, and pretty cute, but what we're doing now is bigger and better.'”

The Future of Predictive Agriculture

Charlie Messina, the associate editor for this special section in Crop Science, sees the section as a means of connecting all of the stages of agricultural production, from breeding to agronomic studies, to the management implemented by farmers in the field.

In the introduction to the special section, Messina and his colleagues posit that, “…taking steps to avoid problems is preferable to solving problems once they exist” (https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.20116).

“If you can make predictions beyond what the data are telling you is happening today,” Messina says, “you can anticipate consequences of actions beyond the realm of what is known.”

In a practical sense, that could translate to a set of tools for farmers and policymakers that allow them to manage risk. Running models for the next 20 years using one management system with a crop in a certain environment could bring insights into effects on nitrogen efficiency, soil health, crop yield, and environmental impact over time. Armed with that knowledge, stakeholders can make more informed decisions.

For those developing tools used by farmers, making sure that the farmer is involved in the development process is critical. Neal Gutterson, the Chief Technology Officer of Corteva Agriscience, knows that the future of predictive agriculture use on farm lies in innovation and co-creation with farmers.

“Usually, by the time we launch a new product, the innovation is done,” Gutterson says. “You launch, it's done, you hope the farmer loves it. But with predictive agriculture, it's really the beginning of innovation.”

Likewise, John Arbuckle, the Global Leader of Predictive Agriculture at Corteva Agriscience, sees prediction working on farm as an “insight delivery system” for farmers.

“It's not just parsing through data—nobody has time for that, that's out-running a farming operation,” Arbuckle says. Insights about management, timing of fertilizer application or pest control solutions, or integration with remote sensing techniques could be rolled in with prediction.

“We're trying to empower growers to make the right decisions,” Messina says. “These prediction tools are the right way to do it. We can deliver value for the grower and society.”

Whether prediction helps breeders to develop better genotypes in conjunction with agronomists, or farmers to apply the most efficient amount of nitrogen fertilizer at the perfect time in the growing season, or stakeholders to understand how management practices will affect farm outcomes for a season or five years to come, predictive agriculture is at the cusp of agricultural innovation.

DIG DEEPER

Check out the “Predictive Agriculture” special section in the upcoming March–April 2020 issue of Crop Science (https://acsess.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/14350653).

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.