Plant blindness: How seeing green creates cultural disengagement with agriculture

- “Plant blindness” is an inability to see or notice details about plants in one’s environment.

- Researchers at North Dakota State University demonstrated “plant blindness” in third-grade students by asking them to draw plants they viewed on-site.

- Insight into “plant blindness” can help scientists and researchers connect more meaningfully with students and members of the public through education and outreach.

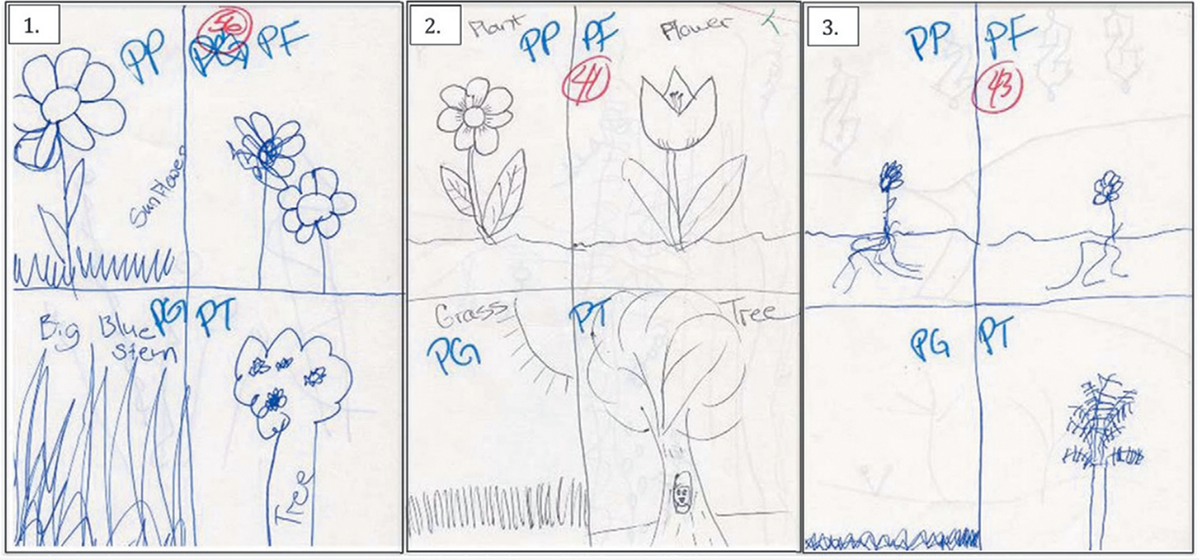

When the third graders on a field trip to Minnesota State University Moorhead (MSUM) Regional Science Center were asked to draw a plant, 66% of them drew a daisy. You know, the daisy you doodle on your phone pad during a particularly long call, after you’ve already written down the number you need.

Ranging from 8 to 10 years old, these third graders represent a pivotal point in development when we begin to stop drawing details from what we see and instead rely on mental models of remembered images. Research from Koppitz in 1968 suggests that the drawings completed by third graders is representative of the same drawings a novice adult would complete.

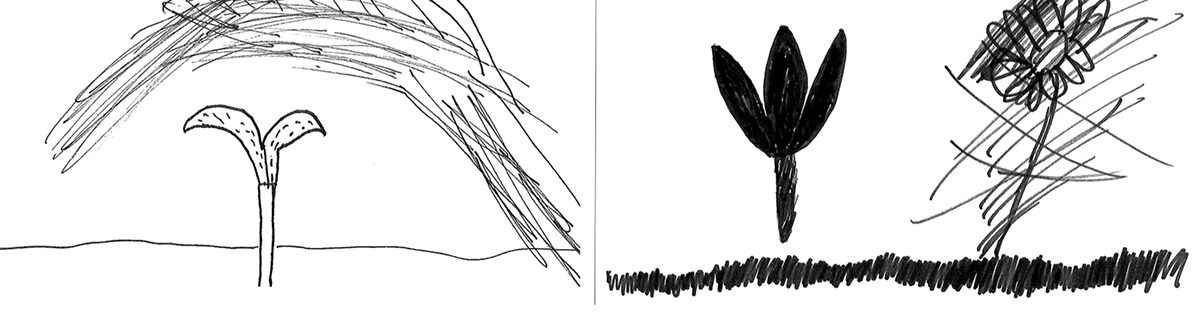

“I actually couldn’t tell the difference between some of the teacher drawings and the kid drawings in a lot of cases,” admits Paula Comeau, a North Dakota State University (NDSU) graduate and English Department professor. Drawings consisted of classic cartoon daisies, grass made up of slashed black lines, and cloud-shaped trees—or rather, blobs with two stick-figure legs. There were no signs of distinguishing characteristics like individual leaves or branches, proper venation or stem configuration, or attention to accurate detail.

This study, published in Natural Sciences Education (https://doi.org/10.4195/nse2019.05.0009) and spearheaded by then-Ph.D. candidate Comeau, used drawing analysis to figure out how, exactly, kids see plants.

Originally, Comeau thought that having kids draw plants in the field would help her discover how she could modify field guides so that they are easier to understand. “The more we dug into it, the more we realized that the field guides were appropriate,” Comeau says. “It’s just that people don’t see things.”

Lost in a Sea of Green

This phenomenon has a name: “plant blindness.” Coined by botanists James Wandersee and Elizabeth Schussler in 1998, it describes the “inability to see or notice the plants in one’s own environment.” Comeau, along with her colleagues at the MSUM Regional Science Center, frequently led specialized K-12 class field trips where they asked student groups to draw a flower so that the field trip leader could come back later and find it, using just the drawing.

“What came back was that these drawings were horribly inaccurate…It wasn’t just that they were bad drawers—there was something preventing them from seeing the plants accurately in a lot of ways,” Comeau explains. “They’re looking right at the plant, standing 5 ft away from it, and they’re drawing tulips on poison ivy.”

But the problem runs deeper. Biology textbooks dedicate less space to plants compared with other forms of life, and elementary school teachers may be prone to condensing plant units in favor of the more “exciting” lions, tigers, and bears.

“You look at a dog from a very young age, and you know that it’s going to have four legs and paws,” says Christina Hargiss, a professor of Natural Resources Management and Comeau’s adviser at NDSU. “You look at a duck and know…that it’s going to reproduce by egg rather than live birth. Those skills don’t transfer to plants. We don’t know those things at a young age, and we don’t learn those about plants until we go to college and only if it’s part of our major.”

There are several theories as to why plants fade into the background of the average individual’s day-to-day life. “Plants are non-threatening. They’re not in your face, causing problems,” Hargiss said. Plants have no teeth or claws (usually), stay in one place, and are all the same color. To the average individual, plants may fade together into a uniform wall of color, with individual species and their importance lost in a sea of green.

Implications for Conservation, Agriculture

This lack of knowledge has troubling implications for public views on conservation and agriculture. This “dismissal view” of plants translates into decreased environmental literacy in the public sector. It is difficult to understand the importance of different crops when you can’t even tell that they are different crops.

Comeau and Hargiss both had suggestions for ways that scientists and researchers can combat plant blindness, bringing attention to a critical sector of our economy and our lives. Encouraging people to go out and experience nature is important. “It’s really hard to appreciate things you have no experience with,” Hargiss says.

Likewise, Comeau, in her capacity as a naturalist, leads a “tall grass prairie meditation” where people are encouraged to lie down and look up at the grass overhead. “The number one comment I get is, ʻI didn’t know there were so many different plants in the prairie!’” Comeau said. “And it’s like, well, yeah, it’s one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in the world. Surprise!”

Another way to encourage plant literacy is to discuss where food comes from. Everyone must eat every day, and so showing people how wheat looks before it becomes bread, or how peas look planted in a field, could be a way to engender understanding. In turn, that understanding could deepen into empathy and concern for agricultural issues.

Moving forward, Comeau plans to look deeper into the cultural roots of plant blindness. Children’s books are one arena for further research. “If we spend all of a child’s early years exposing them to inaccurate images of plants, they’re probably going to have an inaccurate image of a plant serve as their mental model as they go through life,” Comeau says.

Finding out how that mental model comes to be—whether through exposure to media or through cultural values—could provide insight into ways to combat plant blindness at a fundamental level. The NDSU researchers have plans to examine Native American views on plants and potentially compare plant literacy for individuals raised with differing cultural values or in other areas of the world where plants may have more charismatic features.

In short, coming to terms with the way educators, scientists, farmers, and parents can encourage the next generations to truly see the diversity of plant life around us may make a critical difference when questions of agricultural policy or plant endangerment come to light.

DIG DEEPER

Interested in this topic and want to learn more? We’re dedicating two episodes of our podcast, Field, Lab, Earth, to it this month (release date: 6 Mar. 2020)! Listen now by scanning the QR codes below with your phone or visiting https://apple.co/2SpCoGs for Apple devices or https://bit.ly/2Sqf7nM for Android.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.