Transforming crop breeding in the developing world

The challenge of sustainably feeding a growing population is daunting, especially when there are currently more than 800 million people who are malnourished and starving worldwide (www.fao.org/hunger/en). In addition, the current COVID-19 crisis and desert locust outbreak threaten to increase the number of people around the world who suffer from food insecurity. These crises highlight the need for a modern food system. Modern agriculture can feed people, reduce poverty, and improve livelihoods, but tools and technologies must keep up with the changing world. Plant diseases, resource scarcity, and a changing climate impact yields, requiring better varieties and new technologies simply to maintain the current rate of production. In the United States, modern techniques like molecular breeding, remote soil and water sensing, automated cropping, and advanced pest and weed control have allowed for a continued increase in yields. In contrast, the developing world still lags behind.

The Stalled Green Revolution

In the 1960s, the Green Revolution changed modern agriculture. Breeders selected traits that led to new disease-resistant, high-yield varieties of wheat. In combination with new mechanized agricultural technologies, countries transformed their economies and became exporters of crops. Crop improvement methods for wheat were translated to other staple crops, increasing the availability of food and fodder. Although adoption was slow in the developing world, second-generation improved varieties eventually made it to the field.

But there is a problem. Many of those improved varieties are still in farmers’ fields decades later. For example, the average varietal age of maize in Kenya is 15–20 years, and the average varietal age of rice in India is more than 25 years. Compare that to the United States where the average age of a variety in a farmer’s field is three to five years (https://bit.ly/376AukT). Part of the reason for the stalled variety adoption is that current varieties don’t sell themselves the way the initial varieties did. New varieties often look similar to older varieties. And while new varieties can be better suited to the current environment, the difference hasn’t driven adoption by farmers.

Modern breeding systems can deliver genetic gains of greater than 1.5% annually. In comparison, genetic gains in research plots in many developing country breeding programs are closer to 0.5% annually. Importantly, these gains are likely lower in the farmers’ fields. So, it seemed clear: modernizing breeding programs should lead to increased genetic gains and variety turnover. But is modernizing alone sufficient? Simply putting modern tools in a breeder’s hand may not be as powerful as using purpose-driven breeding to give farmers the specific traits they are looking for.

Modernizing Crop Improvement

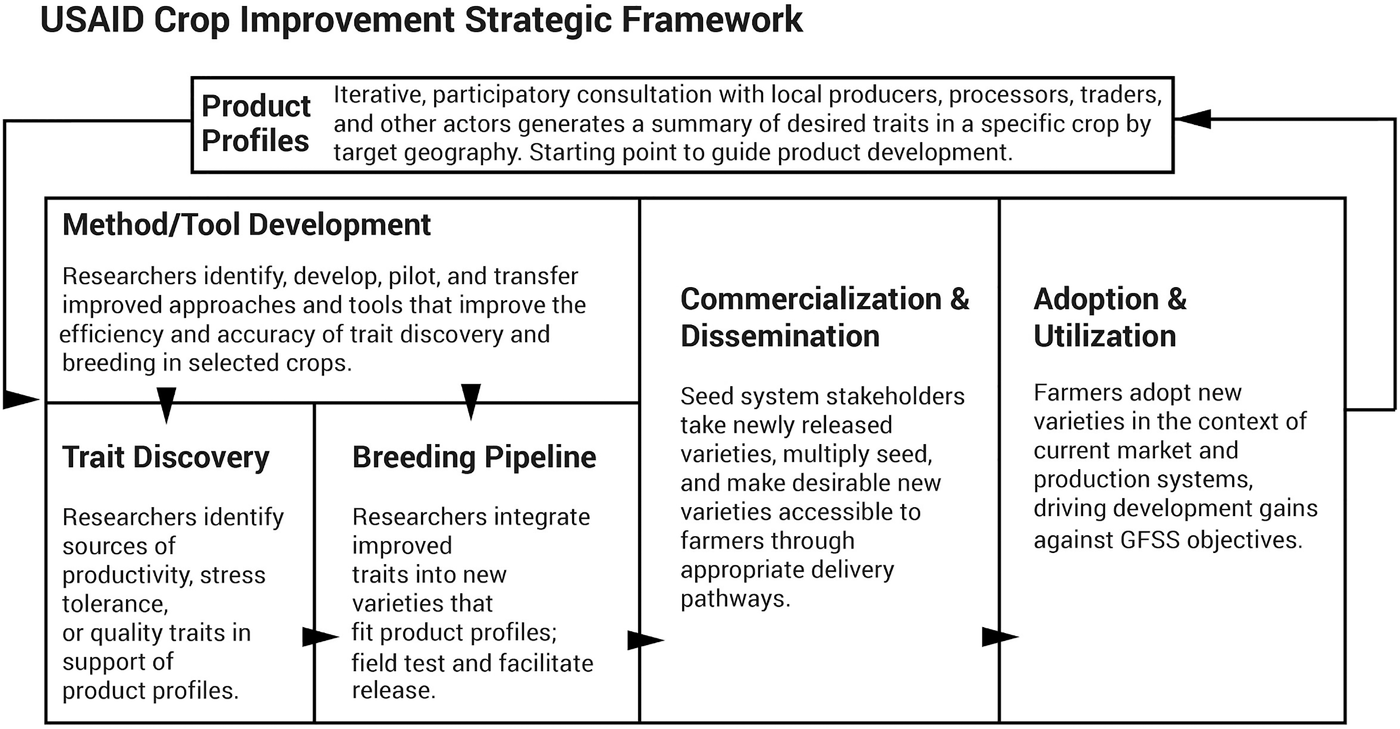

USAID’s Bureau for Resilience and Food Security is responding to the need for breeding modernization through a recently redesigned Crop Improvement Strategic Framework (Figure 1). The framework recognizes that modernization of breeding programs must be purpose driven to make the largest positive impact.

Modernization must start with a recognition that crop improvement should be deliberate; product profiles for new crop varieties should be designed with farmers and consumers in mind. Product profiles that are designed in consultation with key actors along the supply chain are likely to ensure that more varieties make it into farmers’ hands. Additionally, investments in breeding should be made with a prioritization of specific crops in appropriate geographies, based on strong market research (https://bit.ly/2XzpWYo). When developing a new variety, breeders must follow a standardized system with clearly defined metrics for success, similar to R&D pipelines found in private breeding programs. Taken together, the hope is that more varieties will move from research plots into farmers’ fields.

Additionally, breeders need access to better tools, technologies, and methods. This includes better data collection and management systems, utilization of genomic selection approaches and improved phenotyping, and better field trials and on-farm testing. Better tools and methods will feed into trait discovery and the breeding pipeline, accelerating new traits and new varieties. Oftentimes, the hand-off of new varieties from research to commercialization never happens, and new varieties land in the so-called “valley of death.” To improve this transition, once new traits are identified, there need to be strong links among researchers, seed systems, and end-users.

Lastly, a modernized crop improvement system requires investments in human and institutional capacity. This must go beyond the hiring of staff or purchasing of equipment. It must include training all along the value chain—from researchers, breeders, and extension agents to farmers and consumers, and these efforts must be inclusive of women and youth.

Current Initiatives Aimed at Achieving Gains

In order to work towards our crop-breeding goals, USAID is investing in crop improvement research through U.S. university-led Feed the Future Innovation Labs, the CGIAR international agricultural research system, National Agricultural Research Extension Systems (NARES) in partner countries, and the private sector. For example, USAID recently launched a five-year, $25 million activity led by Cornell University. The Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Crop Improvement is developing plant-breeding tools, technologies, and methods aimed at delivering staple crops with increased yields, enhanced nutrition, and greater resistance to pests and diseases (https://ilci.cornell.edu). The Innovation Lab brings together experts from Cornell, Kansas State University, Clemson, and USDA-ARS, along with researchers in our partner countries, to focus on five main areas of inquiry: priority setting, trait discovery, phenomics, genomics, and breeding informatics. The Innovation Lab has already identified “quick win” activities that cover a diverse set of crops, geographies, and areas of inquiry.

Along with the BIll and Melinda Gates Foundation and other key donors, USAID is supporting the CGIAR Crops to End Hunger Initiative (https://bit.ly/2AKrA08). This is another example of shifting breeding programs to develop and deliver more productive, resilient, and nutritious varieties of in-demand staple crops to smallholder farmers and consumers in various geographic regions of the developing world. Key principles of Crops to End Hunger reflect the needs of a modernized breeding program. These include a focus on demand-driven product profiles with clear metrics for moving a variety through the breeding pipeline. To help programs achieve this, the CGIAR Excellence in Breeding platform (https://excellenceinbreeding.org) will deploy a stage/gate process that aims to improve accountability and increase consultation along each stage of the breeding pipeline. Ultimately, strengthened connections and partnerships with national programs and the private sector will be essential to facilitate uptake of improved varieties. Success and impact will be measured by genetic gains and average varietal age in farmers’ fields.

The Future of Crop Improvement

USAID’s strategic vision for crop improvement signals a new way of thinking about modernizing breeding programs. Our investments will reflect this modern approach and present new opportunities for the scientific community to get involved.

Additionally, fallout from the ongoing COVID-19 crisis and desert locust outbreak makes it clear that research investments should be viewed using a global, modern lens. Smart, evidence-based crop improvement research can enable a more resilient food system in the future, mitigating primary and secondary impacts from the inevitable next crisis, whether it be a pest, pandemic, or climate shocks. Taken together, the hope is that USAID’s new crop improvement strategy will advance food security, reduce poverty, and improve nutrition during times of stability and in times of crisis.

Text © . The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.